by Glauco D’Agostino

Islamists and Nationalists at the dawn of a new Mali, a politically and militarily correct State

Last December the parliamentary elections in Mali (with the prevalence of social-democratic Rassemblement pour le Mali) and the previous election in August of Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta as President of the Republic have completed, at least formally, the institutional transition that began in April 2012, following the coup against President Amadou Toumani Touré.

Of course, as often the case these days, it’s a democracy forcibly imposed by arms with a taste of neo-colonial flavor: both elections have been held with the presence of 3,000 French soldiers and 6,000 military of the Minusma UN mission, after France, helpless when the military had broken Malian democracy, on the other hand, had intervened in January last year by the Socialist Hollande’s Serval military operation, when the coup-rooted regime had lost control of the Azawad northern territory in favor of the Tuareg Islamists.

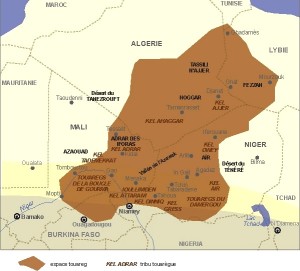

The Tuaregs, a Tamazight-speaking group of nomadic tribes living today in the Saharan and Sahelian regions of Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso, Algeria and Libya, are cultural and ethnic minority in all countries where they reside. The tribal structure of their social composition helps to understand the historical difficulty of French colonizers to integrate them into institutional setting, first of French West Africa and then, during the transition to independence, of the uprooted young State entities: in these new realities, Tuaregs can be found split in several nations, by sharing the same space with other ethnic groups with completely different costumes (Bambara, Peul, Malinké, Soninké, Bozo, Toucouleurs, Songhai) and often being marginalized compared with these ones. For example, the opportunity to use their own language at schools and in the media has always been a reason for cultural claims, alongside with the defense of their economic and territorial prerogatives and the call for an improvement of social services (health and education facilities, extension of the wells and food distribution network, road infrastructures, special terms of energy costs, crime fighting).

May also be explained this way the numerous rebellions erupted in Mali and Niger, among which we recall:

- the 1916-17 riots against the French;

- the 1961-64 revolt, countering the land reform introduced by the new socialist Republic of Mali, and that, following a brutal crackdown, saw one of its protagonists, Zeyd Ag Attaher, son of the Tuareg Ifoghas’ Amenokal (tribal Chief), confined a few years later at the Taoudeni salt mines, in the northern Malian desert, one of the most remote Earth prisons;

- the 1990-95 uprisings in Mali, which began in the last months of the Moussa Traoré’s regime and finished in the first period of the Alpha Oumar Konaré’s presidency, and the contemporary one exploded in Niger, aimed to the autonomy, and resulting in an agreement for a greater share of the mining revenues in favor of Tuaregs;

- the February 2007 insurgency, again in Niger, and this time finalized to a larger share of uranium exploitation revenues, a request conflicting with the interests of some French dealerships settled in that area (see the Imouraren fields, which are among the largest deposits in the World).

The April 2012 Declaration of Independence of Azawad, almost contemporary and in reaction to the military coup, it fits, as a result, in this context of Tuareg unrest, steeped in a secular social marginalization and led in a tough life between drought and famine, among government promises and harsh repression of protests. It’s clear that the discontent roots are to be sought in the mistakes made at the independence time in drawing the new territorial and institutional Mali; therefore, errors of French source, which, 50 years later, are compounded by a military “paternalism”, superficially and demagogically cloaked in anti-terrorist purposes.

Doubtless, the democratic process led since the French intervention could still go towards a recovery of Tuareg noncompliance, also because the June 18th Interim Agreement of Ouagadougou (which enabled the accomplishment of presidential and legislative elections) has gathered around the Burkinabé mediator Blaise Compaoré both the Malian governmental authorities and the Tuareg fighters of newborn High Council for the Unity of Azawad, of the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad, and of the Popular Front of Azawad. Islamists of ʾAnṣār ad-Dīn and of Movement for Oneness and Jihād in West Africa were absent from the negotiating table.

The following picture provides an account of the existing differences among the main Tuareg movements, which can be so broadly determined:

- the loyalists to the Republic of Mali, such as Colonel Major Alhaji Ag Gamou, former Chief of Staff of Malian President, later adherent to the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad, and further back in defense of regime;

- the federalists of Popular Front of Azawad (FPA), an inter-ethnic movement (Tuareg, Songhai, Arabs and Fulani), led since its foundation (2012) by Colonel Hassane Ag Mehdi;

- the secular Nationalists, mainly grouped around the 2011-born National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA), which lost military superiority in the North in favor of the Islamists. Following the French intervention, MNLA resized its aspirations, by seeking, at least over the short term, a more achievable autonomy;

- the autonomist Islamists of the High Council for the Unity of Azawad (HCUA), founded in Kidal in May 19th, 2013 from the melting of the Islamic Movement of Azawad (MIA) of Algabass Ag Intalla, son of Intalla Ag Attaher, the Tuareg Ifoghas’ Amenokal and Chairman of HCUA;

- the jihādist Islamists of Iyad Ag Ghaly’s ʾAnṣār ad-Dīn (Defenders of Religion), a 2012-founded group aimed to the Sharī’a application and to the establishment of an Islamic State, even though not necessarily separate from Bamako, as MNLA pursues looking ahead;

- the jihādist pan-Islamists of the Movement for Oneness and Jihād in West Africa (MUJAO), a mid-2011-born movement meant to bring Islamist insurgency in West Africa, with northern Mali seen as a sector of a wider jihād. For this reason, some analysts have been erroneously assumed it’s an offshoot of al-Qāʿida in the Islamic Maghreb, despite the patent opposition of the latter Algerian leadership about the opportunity to pursue early creation of an Islamic State in Mali.

Definitely, other external Islamist groups are active in Azawad, by primarily pursuing goals of enlargement their militant bases and this could explain the success achieved by ʾAnṣār ad-Dīn among young people in offering a strict Islamist model adhering, at the same time, to the Tuareg tradition. Among the exogenous movements there are, for example:

- the Deobandi Tablighi Jama’at (Group for the Diffusion of Faith), a 1926-born pacifist trans-national missionary movement originated from India and active in northern Mali since the 90’s of last century. According to the international organization for conflict prevention International Crisis Group, the entire leadership of the Kidal Tuareg Ifoghas, including Intalla Ag Attaher and Iyad Ag Ghaly, had converted to the Tablighi; but a large body of evidence suggests that, among the elders Ifoghas, just Ag Ghaly and a narrow circle close to him would have embraced this doctrine;

- the Saudi-inspired Wahhābis of the Signed-in-Blood Battalion, founded in 2012 by Mokhtar Belmokhtar, the former Algerian Commander in the Sahara-Sahel of an independent group of al-Qāʿida in the Islamic Maghreb. Based in Gao, where Islamist fighters were well received by many people when the town was captured by MUJAO, the Battalion was established for the consolidation of Sharī’a in northern Mali and is opposed to the Sufi Confraternities traditionally active on this territory;

- the Salafists of Tanzim al-Qāʿida fī Bilād al-Maghrib al-Islāmi (Organization of al-Qāʿida in the Land of the Islamic Maghreb), the new name of the Algerian Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat since January 2007, after the holy union with al-Qāʿida announced by Shaykh ʾAyman aẓ-Ẓawāhirī a few months earlier. Devoted to the spread of Sharī’a and also committed to the liberation of Mali by the alleged French colonial rule, the organization recruited militants in Mauritania and Morocco, as well as in Mali, Niger and Senegal.

The 2012-13 Malian crisis follows a long period of Islamist movements revaluation as political subjects and a deep reflection on the relationship between national identity and religious identity: this discussion involves Tuaregs on how to enforce a match between ethnicity and Islam. In other words, following the wretched experiences of the Modibo Keïta’s socialist government in the 60’s (which had obscured Islam and its reformist efforts), by the advent of Konaré’s rule, the first democratically elected President in 1992 and 1997 who would have sponsored the establishment of the High Islamic Council of Mali in the early 2000’s, many Muslims, particularly in the North, had a chance to show their growing aversion to Bamako, by acquiring new opportunities for political legitimacy and by requiring reforms towards Islam. But, following the 1996 peace agreements, Tinbuktu, Gao and Kidal northern regions were left even more isolated and, at the same time, saw the formation of local Islamic associations, as well as attracted a lot of allogeneic-inspired ones, in particular from Saudi Arabia and Pakistan. Moreover, in recent years there has been an open debate about the nature of a secular State and the role of Islam in politics. For example, the Wahhābi Imam Mahmoud Dicko, President of the High Islamic Council of Mali and native to the Tinbuktu region, rejects a vision of secularism as “a denial of religion by the State”, calling for a “smart secularism”, where “everyone’s rights are respected”, according to the constitutional principles of worship freedom.

In this context, the 2012 Tuareg rebellion had begun, in conjunction with the March military coup, with the request for independence of Tinbuktu, Gao and Kidal regions, drawn by the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad of Bilal Ag Acherif, its Secretary-General, and Moḥamed Ag Najem, head of its military wing. MNLA leadership had been soon challenged by ʾAnṣār ad-Dīn Islamists, who, already rooted in the Kidal area, conquered Tinbuktu in May, and by June, with the involvement of MUJAO pan-Islamists, defeated the secularists in Gao. In the name of dialogue, negotiations with the government in Bamako started immediately, not only on behalf of Tuaregs, but also of other ethnic groups traditionally at odds with them, such as Bella and Songhai: it’s an indication of a religious motivation, which now overlaps with territorial claims. An Islamist effort to gain Mopti region early in January 2013 broke at French intervention, which was MNLA-backed in the vain hope of regaining control of the north for its own benefit: by the end of the month the entire Azawad was once again subjected to the Malian government and the French military protection.

At the moment, with a completely refurbished institutional context, the new Mali has an opportunity to retrieve the Tuareg and Islamist dissent that has been crossing its history since the outset. Surely, Bamako (along with Paris, Washington and Algiers) won’t allow separatist leak in the short term, as well as won’t allow alleged extremist Islamic factions to influence the Malian political agenda. The democratic weapons of fraternal supervisors, rather than the will of its political components, ensure it, being always on alert. Just as certainly, the public role of Islam, even though within the framework of a secular State, cannot be rejected into the recesses where it had been confined in the 60’s. Decades have passed since then and, undoubtedly, its awareness has been generally strengthened by the war events, even right by the resizing of its more radical components: after all, the restoration of a likely Malian State legitimacy emanates from a compromise, gaining a strong contribution by autonomist Islamists, as well.

This discussion is directly pouring on the constitutional choices politicians are called to foster and that will be so much more consistent to social reality as much as ruling class will realize the influence some deeply rooted social groups exert on public opinion: in other words, the bodies of political representation not always can act on its own, even legitimately, regardless of popular feeling and its need to participate in decisions. For example, the fierce Islamic opposition to certain provisions of the new 2008 Family Code introduced by President Amadou Toumani Touré bears witness, because it led to the immediate withdrawal thereof, as a result of a large mass rally held by the High Islamic Council of Mali.

Likewise, Tuareg demands for autonomy cannot be again overlooked on the basis of a military defeat, but also assessed and discussed in order to introduce policies for fighting ethnic and social marginalization and discrimination, setback in economic conditions, lack of development, territorial depletion, political exclusion; and, at the same time, to start policy in support of local institutions and regional cooperation. Perhaps, these are the interventions northern populations expect from those who care about their condition (State or subjects frequently substitute of its authority, see political or religious organizations), failing which hardly the military cure occasionally offered will absorb dissent.

Finally, Mali can be saved and define its “Malian” future if, while respecting its international loyalty, it will be able to reject some approaches – these, sure, seriously allogeneic! – imposing shallow, but utilitarian “Western” simplifications, that is Tuareg = Islamists = extremists = al-Qāʿida = terrorism, resulting in a democratic military action. These approaches are very comfy if regarded from the opulent Paris or Washington, much less if experienced by anguished Bamako and Tinbuktu.

However, there is time. The Tuaregs, as a millennial Saharan people, hope and are very patient. For now…