Next presidential elections in Iran follow a US change of course. Their mutual relationships have been full of contradictions, but not always have led to a real clash. Will the White House and its diplomacy be able to deal wisely with a key geo-political confrontation?

By Glauco D’Agostino

Election uncertainties in Iran and still open disputes with the US

President Ruhani is ready! Likely, the religious man is preparing for a domestic battle in next May presidential elections with no credible rivals in the reformist camp, but, at the same time, will face a stiffer conservative coalition than a few months ago, just by virtue of the international changing conditions. First and foremost, the advent of a White House new roomer. Because there’s no question the Obama-Ruhani duo, apart from judgments anyone could give on each statesmen, eased relationships between US and the Islamic Republic, enabling the former to gain credit (rightly or wrongly) as a sample of multilateralism and cooperation, and the latter to drop an ideological veto over its political structure (deemed as to be few available for compromise) and enter again the global economic system.

Today, with a new policy launched in Washington, a Trump’s attitude perceived (rightly or wrongly) as to be an anti-Islamic may lead strengthening the fundamentalist components sitting in the Iranian Parliament, such as the Front of Islamic Revolution Stability and the Front of Followers of the Line of the Imām and the Leader (backed by traditionalists of the Islamic Coalition Party), or the ones active in the civil society, such as Yekta (Unique) Front. The latter was founded in 2015 as an informal party by figures close to former President Maḥmūd Aḥmadinejād, and precisely his line is regarded by many as an offset sufficient to counter the aggressiveness of Trump’s US. Basically, the greater the White House vehemence against Iran and the Islamic world, the greater the chance of a purely defensive fundamentalist stance in Tehrān future policy. Surely, given by now decades-long ties between Iran and Syria, the latest events of a US bombing of a Syrian operational base for military action against the Islamic State don’t help, also because President Trump adopted this one-sided decision at odds with any international requirements and with any consensus from UN, and even from the Congress itself. And the outstanding Trump’s divination skills about certain terrorist attacks in Europe definitely amazed. All provocative elements that, it’s sure, Tehrān don’t like.

Former President of Iran Maḥmūd Aḥmadinejād (centre) with President of Siria Baššar al-Asad

In the current situation, two subjects are creating a contrast between the US and Iran, which, by the way, don’t have formal diplomatic relations:

- The implementation of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA, or BARJAM in the Persian language), the international agreement requiring Iran to drastically cut its nuclear program in return for a gradual lifting of sanctions, and that President Trump would like to dismiss, or at least renegotiate, as already he announced in his presidential campaign;

- The restrictions of immigration in the US from six Muslim-majority countries (including Iran), which President Trump is trying to introduce by a disputed executive order.

As for the first issue, while Trump regarded the agreement with Iran “one of the worst deals ever made by any country in history”, the Iranian stance was effectively expressed on March 16th by Foreign Minister Moḥammad Javad Zarif in an interview with the Lebanese TV channel al-Mayādīn, in which he has substantially stressed:

- The ineffectiveness of US sanctions against Tehrān, which, rather than being eased, have been tightened last February 3rd, even though relevant Iran violations are not reported;

- “The biggest nuclear threat both to the region and the world” consisting of the “Zionist regime of Israel”.

Also about the second theme, on previous January 28th (that is, the day after Trump signed the executive order Protecting the Nation From Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States) Zarif had remarked: “An obvious insult to the Islamic world and in particular to the great nation of Iran”. On February 3rd, the Āyatollāh Aḥmad Khātamī, senior member of the Assembly of Experts of the Leadership and Tehrān Friday Prayer Imām, expressed the resentment of Iranians in his sermon: “The US message comes from who is fighting against religion and Islam … Thousands of Americans were killed in Saudi Arabia, but not a single American was killed in the seven Muslim-majority countries included in the ban list”.

The topic is highly contested within the US, as well, since Trump’s executive order would violate constitutional provisions. Following a January first block by a Seattle judge, even two federal judges from Hawaii and Maryland did the same thing in mid-March, the former arguing that national security reasons are questionable, and both of them calling upon a violation of the First Amendment of the Constitution on religious discrimination. Trump denies discriminatory intent. On the other hand, his anti-Islamic intentions had been disclosed by himself in 2015, when he called for “a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States”. This is reminded by Hawaii Judge Watson while enforcing the grounds of the judgment.

Jamāl Abdi, the Executive Director of NIAC Action (branch of the National Iranian American Council), which has the task of supporting the Iranian nuclear deal and defending the Iranian Americans priorities, said: “I have a hard time seeing how anyone (in Iran) advocating for engaging with the United States has any kind of political capital now”. Nihād ʿAwaḍ, the Executive Director and a founder of the Council on American-Islamic Relations, has no doubts on Trump’s new immigration policy: “It will hand a propaganda tool to our enemies who promote the false narrative of an American war on Islam”. A fully consistent behaviour with the one from some protesters who, during last February 10th demonstrations at Freedom Square in Tehrān showing Trump’s, Netanyahu’s and Theresa May’s images with the words “Death to the Devil Triangle”, carried banners that read: “Thanks to American people for supporting Muslims”. Even the Jewish Voice for Peace has launched an appeal from America to “resist in every way possible. We’ll put our hearts, souls, and bodies on the line to stop these hateful and racist attacks. We all belong here”.

Historical structural disagreements and Tehrān geo-political aspirations

Of course, JCPOA and immigration restrictions are contingent elements which are part of a suspicion and opposition context since the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Since that time, the two countries foreign policies have been divergent and involved constitutive (and therefore long-term) matters, such as:

- The Iranian resolute independence from both Cold War blocs led by the US and USSR, allies in the WWII and till 1989 relentless in retaining their dominion over the world. Even after the disastrous communist power defeat in the USSR, the Islamic Republic has kept its own autonomous policy not dependent on foreign interests, while preserving nation roles, culture and traditions. The United States responded smacking Iran by epithets such as “terrorist state” and “part of axis of evil”;

- An antithetical approach in the Middle East and North Africa, with US supporting Israel, Saudi Arabia and Egypt (from Mubārak to Sīsī), and Iran protecting Syria of `Alawite Asad rulers, Ḥizb Allāh and the Palestinian reasons for clearing the occupied territories;

- The American attempts of interfering in Iranian domestic politics, all failed supposedly to poor understanding of a theocracy and Islamic democracy admixture and of the complex structure of Iranian institutions. Washington do and did justify this interference by alleged ideological reasons to oppose a so-called “outpost of tyranny” and promote a “Western” democracy, in contrast to its support for dozens of military secular regimes in the world, including the Middle East;

- A veiled US support to the Mojāhedīn-e Khalq-e Irān radical-Marxist group (People’s Liberation Army of Iran), described as “involved in terrorist activities” by the UN, earlier utilized by the US and Ṣaddām Ḥusayn in an anti-Iranian role in the 80’s war, and then regarded by the US itself as a terrorist organization from 1997 to 2012 (because of attacks against Iranian institutions and assassinations of thousands of Iranians);

If this is the structural framework (also a pretty obvious and ideological one), few analysts highlight an evidence arising from the facts. I mean that, at least since 1986, the mutual verbal violence has matched a foreign policy of the White House (and its guests, both Democrats and Republicans) that in some ways encouraged Iran, enabling it to gain a regional role, which its “theocratic regime” legitimately aspires to. Basically, thirty years of US policy in the Middle East led to the weakening or removal of all real and potential, institutional and political enemies that might limit its expansion in territorial influence. To the east, the Tālibān (founders of an Islamic Emirate, but a Sunni one) and al-Qāʿida (which had contributed to the victory on the USSR, but made up primarily by Wahhābi fundamentalists). To the West, a secular and Ba’athist (as indeed Syrian Asad rulers) Iraq of Ṣaddām Ḥusayn, a slayer of Shiites, as from Grand Āyatollāh Moḥammad Baqir aṣ-Ṣadr, a direct descendant of the 7th Twelver Shiite Imām Mūsā al-Kāżim and 5th Shiite martyr.

Since September 11th, the US has started fighting the Sunni Islamist fundamentalism, targeting, after Ṣaddām Ḥusayn, even the Ḥaqqānī network in Pakistan and the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq. Obviously, Washington policy has never jeopardized the stability of Turkey (a NATO ally), Israel (being its main sponsor) and Saudi Arabia and its Gulf satellites (due to oil reasons); and it’s no coincidence that just the latter regional players are the most worried about an enlargement of Iranian viability in the Middle East, starting from its influence on Yemeni Ḥūthis, keeping on Ḥizb Allāh master role to support Asad, ending with a refreshed Tehrān nuclear intention. This is why Israel and Saudi Arabia have opposed Iran rapprochement to Washington and Moscow and disapproved JCPOA. Today, their respective powerful lobbies are trying to ride the new and confused Trump’s foreign policy strategy, by seeking to influence his options. But, as we might see from the foregoing, we can hardly charge only Obama with a political opening to the Āyatollāhs, by basing it on ideological and pro-Islamism premises, and anyone can hardly play the card of an alleged US Islamophobia in order to win a lost space on geo-political ground.

King ‘Abd Allāh of Saudi Arabia (left) and the Israeli Binyamin Netanyahu

The nuclear issue

The Iranian nuclear issue dates back to the 50’s of last century, when President Dwight Eisenhower, in the wake of his famous “Atoms for Peace” speech at the UN General Assembly on December 8th, 1953, four years later promotes the Iran-United States Agreement for Cooperation Concerning Civil Uses of Atomic Energy, allowing transfer enriched uranium to Iran. Then, Tehrān signs the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons in 1968, ratified by its Parliament in 1970, and in 1975 President Gerald Ford allows the use of US fissile material in Iranian reactors and the purchase and management of US nuclear reprocessing plants for extracting plutonium from the reactor fuel. All this is justified on the grounds that Iran of Shāh “was an allied country, and this was a commercial transaction”, to quote 2005 Henry Kissinger’s words (pictured below with the Shāh), at the relevant time in office as Secretary of State of Ford Administration.

Following the incoming of Āyatollāh’s system in the late 70’s and the long war with Iraq, in the mid-90’s Iran announces a future deal with Russia in order to complete the Būshehr nuclear power plant on the Gulf coast. But it’s not prior to 2002 that especially the US and Israel denounce an alleged Iranian clandestine program of nuclear weapons, across an uranium enrichment plant in Natanz, Eşfahān province, and a heavy-water reactor at Arāk, Markazī province. These are the years after September 11th, when the US and Israel are respectively dominated by the hardliner George Bush Jr. and the extremist Ariʼēl Sharōn, and in Iran President is the reformist Seyyed Muḥammad Khātamī, who is in principle more widely accepted throughout the Western world than a representative of a conservative faction. Nevertheless, the United States uses the aforementioned Mojāhedīn-e Khalq-e Irān radical-Marxist group, which at that time itself regards as terrorist, in order to formulate these allegations against Iran, despite Tehrān denies using its plants for military goals and agrees to welcome inspectors of the International Atomic Energy Agency.

Following the incoming of Āyatollāh’s system in the late 70’s and the long war with Iraq, in the mid-90’s Iran announces a future deal with Russia in order to complete the Būshehr nuclear power plant on the Gulf coast. But it’s not prior to 2002 that especially the US and Israel denounce an alleged Iranian clandestine program of nuclear weapons, across an uranium enrichment plant in Natanz, Eşfahān province, and a heavy-water reactor at Arāk, Markazī province. These are the years after September 11th, when the US and Israel are respectively dominated by the hardliner George Bush Jr. and the extremist Ariʼēl Sharōn, and in Iran President is the reformist Seyyed Muḥammad Khātamī, who is in principle more widely accepted throughout the Western world than a representative of a conservative faction. Nevertheless, the United States uses the aforementioned Mojāhedīn-e Khalq-e Irān radical-Marxist group, which at that time itself regards as terrorist, in order to formulate these allegations against Iran, despite Tehrān denies using its plants for military goals and agrees to welcome inspectors of the International Atomic Energy Agency.

Right on negotiating nuclear issue, a future President Ruhani’s role stands out, when, in his charge of Secretary of Supreme National Security Council and Chief nuclear negotiator in talks with France, Germany, UK and the European Union, in 2004 consented to a preliminary agreement for suspending the Iranian production of enriched uranium, while claiming an Iranian right to nuclear power generation for peaceful purposes. Since 2005, with the Aḥmadinejād’s Presidency and ensuing resumption of uranium enrichment in Natanz, the IAEA tightens its stance, by bringing the Iranian affair to the UN Security Council, which in late 2006 approves sanctions against Tehrān, repeatedly worsened in subsequent years. While Bush, apart from imposing his own sanctions, wants to play (as he has done in Iraq) a role of “unilateral avenger of international order”, he decides to switch to a dirty cyber war, and, with Israel help, in 2008 causes harm to Natanz nuclear production facilities by using computer viruses. It’s a maximum tension time in the US-Iran relations and the one of maximum subjection of Washington to Tel Aviv, where since 2008 the centrist “dove” Ehud Olmert has replaced the “hawk” Sharōn.

A similar pattern lasts when in the US the Obama’s Presidency starts with Hillary Clinton as Secretary of State, two Democrats, and in Israel Binyamin Netanyahu, a neo-Zionist who radicalized during the 1967-70 War of Attrition against Egypt, is back to the Presidency. All together keep the cyber war against Iran and in 2010 hit again, by disabling one fifth of Iranian centrifuges. Only in 2013, with the Catholic Liberal John Kerry’s arrival to the Secretary of State, formal talks for JCPOA among the Islamic Republic of Iran, the UN Security Council five permanent countries and Germany begin. After a year and a half of negotiations, in April 2015 the seven players adopt a framework agreement, and the following July approve the Plan as a whole, along with provisions for reviewing the Iranian nuclear program and a conditioned removal of sanctions. A good omen for more stable relations in the Middle East and Central Asia. Then, Trump’s arrival…

A similar pattern lasts when in the US the Obama’s Presidency starts with Hillary Clinton as Secretary of State, two Democrats, and in Israel Binyamin Netanyahu, a neo-Zionist who radicalized during the 1967-70 War of Attrition against Egypt, is back to the Presidency. All together keep the cyber war against Iran and in 2010 hit again, by disabling one fifth of Iranian centrifuges. Only in 2013, with the Catholic Liberal John Kerry’s arrival to the Secretary of State, formal talks for JCPOA among the Islamic Republic of Iran, the UN Security Council five permanent countries and Germany begin. After a year and a half of negotiations, in April 2015 the seven players adopt a framework agreement, and the following July approve the Plan as a whole, along with provisions for reviewing the Iranian nuclear program and a conditioned removal of sanctions. A good omen for more stable relations in the Middle East and Central Asia. Then, Trump’s arrival…

Yet, the US and Iran itself obsession to nuclear power cannot be understood without put it in the light of a perception of the geo-political framework where the Persian nation is plunged, and that is featured in such a way:

- An estimated oil reserves endowment of nearly 160 billion barrels, that is the fourth in the world (behind Venezuela, Saudi Arabia and Canada), and a 3.6 million barrels daily production; this represents a clear opportunity for international extractive sector, which might invest in Iran up to 200 billion dollars in the near future and, as a result, absolutely does not appreciate sanction enforcement;

- A sensitive position on the Gulf, as a link between the Middle East and Central Asia, which not only compares it (or opposes it) to its neighbours, but sees it to be encircled aloof by five powers equipped with nuclear weapons (as Russia, Israel, Pakistan, India and China are), with a constant presence of US troops (in the Gulf Arab countries, Afghanistan, Iraq, Turkey, Jordan, Egypt, Syria and Pakistan), and Russian (in Syria, Armenia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan), British (in Bahrain, Qatar, Cyprus and Nepal) and Turkish (in Qatar, Iraq, Syria and Cyprus) military bases.

In this situation, it’s obvious that a perspective of stability agreement stands out as a “win-win solution”, and any sabotage would be irresponsible, as well as unintelligible, to the diplomacy and world economy players.

The Iranian aspiration to political autonomy and the Islamic Revolution

Franklin D. Roosevelt, Joseph Stalin and Winston Churchill in Tehrān (photo by Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library)

Actually, in the last century, Persia (Iran since 1935) has not had an easy and quiet history, far from it! But certainly not its fault. Firstly, it didn’t attend both World Wars, just because the perspective of oil exploitation (the first production was in 1908) had led to the 1907 St. Petersburg Entente, resulting in its division into British and Russian spheres of influence and a subsequent Anglo-Russian invasion in 1914; and in the 1943 Tehrān Conference, where the Allies had extended yet two-year-long Anglo-Soviet military presence.

With this background, it was understandable that the Shāh of Iran Moḥammad Rezā Pahlavi regarded the United States, which in the meantime was sending military and economic aid, as to be more reliable than its forty-years-long oppressors, and pursued those good relations with Washington already started in 1883 by his Qājār Emperors predecessors. This was the state of affairs until 1953, when a coup backed by CIA and British MI6 overthrew the government of Qājār nobleman Muḥammad Mossadeq, the National Front head, by then overtly opposed to the Shāh policy. The reason was oil once again, since two years earlier Mossadeq (side photo) had been appointed Prime Minister on an oil industry nationalization program approved by Parliament, and had to face severe repercussions from the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (later British Petroleum). In addition, as usual, a geo-political role was playing a game: Cold War, that is USA-USSR alternative but exclusive domain, had begun. And Iran, which however had been championing by President Truman with respect to Soviet ambitions on its province of Azerbaijan, now, with President Eisenhower at the White House, was paying a price in terms of national political autonomy.

With this background, it was understandable that the Shāh of Iran Moḥammad Rezā Pahlavi regarded the United States, which in the meantime was sending military and economic aid, as to be more reliable than its forty-years-long oppressors, and pursued those good relations with Washington already started in 1883 by his Qājār Emperors predecessors. This was the state of affairs until 1953, when a coup backed by CIA and British MI6 overthrew the government of Qājār nobleman Muḥammad Mossadeq, the National Front head, by then overtly opposed to the Shāh policy. The reason was oil once again, since two years earlier Mossadeq (side photo) had been appointed Prime Minister on an oil industry nationalization program approved by Parliament, and had to face severe repercussions from the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (later British Petroleum). In addition, as usual, a geo-political role was playing a game: Cold War, that is USA-USSR alternative but exclusive domain, had begun. And Iran, which however had been championing by President Truman with respect to Soviet ambitions on its province of Azerbaijan, now, with President Eisenhower at the White House, was paying a price in terms of national political autonomy.

During the 50’s and 60’s , the Shāh policy towards the United States of Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy and Johnson was completely loyal, especially in its role of dike to communism and support for Israel; in return, it required economic aid, offset by domestic reforms. When Nixon Doctrine was launched in 1969 with the subsequent regional powers involvement in the contrast to the Soviets, Iran reached a consent to access substantial military aid, and yet in early 1978 President Carter regarded the country as “an island of stability“, intentionally disregarding signs of people discontent to what was seen as an undue westernization of the country.

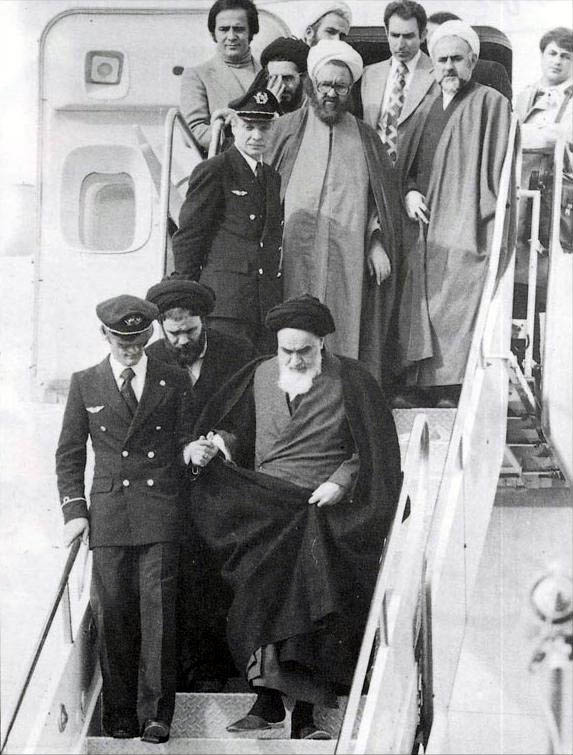

January 16th, 1979, the Shāh, while pressed by his bitter opponent Seyyed Ruhollāh Khomeini (already exasperated by 15 years of exile), left the country after almost a year of strikes and demonstrations. The Sovereign reached first Egypt, but as of next October found a haven in the US at the invitation of President Carter. Meanwhile, Khomeini had landed in Tehrān on February 1st (his arrival in the side photo), and had established the Islamic Republic of Iran next April 1st. The day the Āyatollāh was back, State Department had evacuated 1,350 US citizen: this showed a White House suspicion to the regime change in Tehrān, even though the role of Washington in those January hot days had been ambiguous and, all things considered, open to the new Iranian partners. Whereas on one side the anti-communist barrier reinforced to the south after Soviet invasion of Afghanistan a month earlier, on the other, the revival of an Islamic ruling system (the first one since the Ottoman Caliphate fall) entered elements of unpredictability embarrassing a policy of substantial control over regional powers in the Cold War context. The Islamic Republic arose under “neither East nor West” motto, and promised more important imbalances than those implemented by pretentious Non-Aligned Movement.

January 16th, 1979, the Shāh, while pressed by his bitter opponent Seyyed Ruhollāh Khomeini (already exasperated by 15 years of exile), left the country after almost a year of strikes and demonstrations. The Sovereign reached first Egypt, but as of next October found a haven in the US at the invitation of President Carter. Meanwhile, Khomeini had landed in Tehrān on February 1st (his arrival in the side photo), and had established the Islamic Republic of Iran next April 1st. The day the Āyatollāh was back, State Department had evacuated 1,350 US citizen: this showed a White House suspicion to the regime change in Tehrān, even though the role of Washington in those January hot days had been ambiguous and, all things considered, open to the new Iranian partners. Whereas on one side the anti-communist barrier reinforced to the south after Soviet invasion of Afghanistan a month earlier, on the other, the revival of an Islamic ruling system (the first one since the Ottoman Caliphate fall) entered elements of unpredictability embarrassing a policy of substantial control over regional powers in the Cold War context. The Islamic Republic arose under “neither East nor West” motto, and promised more important imbalances than those implemented by pretentious Non-Aligned Movement.

November 4th that year, President Carter seized an opportunity to break with Iran, when a group of revolutionary students took 60 diplomats of American Embassy in Tehrān as hostages (side photo). Being aware or not of action preparing, Khomeini gave his support to it, causing a Carter’s reaction a week later in terms of a suspension of Iranian oil imports and a denial to the request for the Shāh surrender, as he was hosted in New York to cancer care. Following one more week, seven hostages were released, and after eight months another one was, as well; the remaining 52 would be released after 444 days of captivity. April 7th, 1980, the US broke relations with Iran, and on 17th of that month a mission ordered by President Carter to free the hostages failed. July 17th the Shāh died in Egypt without hostage crisis would hint to end. Their release would have occurred January 20th, 1981, Ronald Reagan’s inauguration day as new US President, following the Algiers Agreements of the previous day, which had taken steps to remove a freeze of Iranian assets (bank deposits, gold and other properties) by the US, and to engage Washington not to interfere politically or militarily in internal Iranian affairs.

Meanwhile, September 21th, 1980, Iraq, whose President and Prime Minister Ṣaddām Ḥusayn had already stood out from the beginning of its mandate to the aversion against the Shiites, had attacked Khomeini’s revolutionary Iran in a war would have lasted eight years. The US lined-up on Ṣaddām Ḥusayn’s side, by providing him with political, economic, military and intelligence aids all wartime, by closing its eyes on his use of chemical weapons, by granting Iraq the removal from the list of state sponsors of terrorism, and by taking sanctions against Iran. However, as the Iran-Contra scandal highlights, President Reagan did not scruple selling weapons to the Āyatollāh Iran, as well, and justified this operation by his will to establish ties with local moderate elements (probably, Āyatollāh Rafsanjani, then President of Parliament) being able to induce Ḥizb Allāh to free American hostages held in Lebanon.

Over and above the real intentions revealed by 1986 inquiries (namely, a diversion of weapons sale proceeds to anti-communist rebels in Nicaragua), just that year reversed a US very hostile tendency to Iran, noting, as well, precisely in the same year the UN Security Council called eventually for a cease-fire, which would have come in July 1988 with a tragic outcome of one million casualties. The US Vice President was George Bush Sr., and it was the last year of Reagan’s Presidency, whom he would have succeeded to. In such a continuity of approach, however, a US acknowledgment of the Islamic Republic soundness was already started, along with a more neutral assessment of its geo-political role, and, indeed, a consequent Middle Eastern policy that would have benefited precisely Iran, as we pointed out above.

The post-Khomeini era

Since Grand Āyatollāh Khomeini’s death on June 3rd, 1989, along general lines the following significant events have affected US-Iran relations:

- The invasion of former ally Ṣaddām Ḥusayn’s Iraq in January 1981, performed by a US-led coalition of 34 countries replying to the foregoing August Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. Immediately, Āyatollāh Rafsanjānī, in his capacity as President of Iran since 1989, arises as a mediator between the US and Iraq, but President Bush’s reaction proves to be cold and willing to break Iraqi Republican Guard’s resistance. The war will stop at the end of February, without Bush will rage so far as to drop Ṣaddām. Despite the formal Iranian opposition to a constant US presence on the Gulf, President Rafsanjānī make known to an audience of foreign security experts that “Iran could accept it as a reality”;

- Democrat Bill Clinton’s set up at the White House in 1993. Two years later, the new President inaugurated a total embargo against Iran to be applied to US companies of all sectors, with a cut-off of an almost growing trade after the war with Iraq ended in 1988. By uncovering the face of his reputation as a “moderate centrist”, in 1996 this embargo will be extended to all foreign companies investing in Iran and Libya, among the European Union’s protests and claims on act nonentity. But motivation supporting embargo is surprising: “the common commitment to strengthen our fight against terrorism … Iran and Libya are two of the most dangerous supporters of terrorism in the world. The bill … will help to deny those countries the money they need to finance international terrorism … and to obtain weapons of mass destruction”. A counter-terrorism rhetoric had begun to endorse a not even as much veiled trade war;

- Muḥammad Khātamī’s election to Iranian Presidency in 1997. The reformist President starts his term by releasing five months after taking office a CNN interview, where he calls for a dialogue with the US in terms of civilizations and cultures and focusing on a willingness of thinkers and intellectuals, in some way discerning between people and governments Khātamī also stresses the religious roots both countries have been established on, and recalls Pilgrim Fathers’ experience. The United States, under a Clinton’s intimidating atmosphere, answers back, by suing the Iranian government to indemnify relatives of an American youth victim of a terrorist attempt with hundreds of millions dollars (a legal aberration!), and by pooling al-Qāʿida, the Islamic Republic and Ḥizb Allāh in an alleged terrorist alliance against it;

Former Presidents of Iran Muḥammad Khātamī (right) and Maḥmūd Aḥmadinejād

- The September 11th attacks.Four months after the event occurred and a year after he took office as President, George W. Bush, during the State of the Union address, invents an “axis of evil”, in which equates Iran, Iraq and North Korea to terrorists, for owning long-range missiles that would threaten US. President Bush is a Republican, but is exactly congruent with Clinton’s line in the anti-Iranian tones; and exactly compliant with US policy since World War II not to tolerate any autonomy that would allow “third positions” than the dominant ones. In the Iranian perception, all this echoes the impositions suffered at the hands of the “Western” powers in 1953 and 1979. Meanwhile, the cumbersome neighbours Tālibān have endured the destruction of the Islamic Emirate, a Shiite Imamate competitor from the doctrinal and supported by Saudi Arabia and Pakistan on a geo-political level;

- Maḥmūd Aḥmadinejād’s rise to Iranian Presidency in 2005. The election of an engineer on fundamentalist stances, following a moderate theologian, is an understandable feedback from Iranian people and institutions to White House muscle policy. An era of escalation on the nuclear issue begins, along with a dirty cyber war and an exasperation of sanctions, which we have already argued about. Meanwhile, the Sunni foe Ṣaddām Ḥusayn has been knocked out by Americans, yet;

- Barack Obama’s election to the White House in 2008. Just two days later, Aḥmadinejād sends the first Iranian message to a newly elected US President after the Islamic Revolution: “I hope you will prefer real public interests and justice to the never-ending demands of a selfish minority and seize the opportunity to serve people so that you will be remembered with high esteem”. It’s a message of congratulations which calls for better relations. As Obama continues the cyber war started by Bush, in 2009 he address the Iranian people, by expressing the wish “the Islamic Republic of Iran to take its rightful place in the community of nations”. At the same time, he calls for “real responsibilities”. A few months later, when President Aḥmadinejād has achieved his re-election, Obama reiterated the message: “If countries like Iran are willing to unclench their fist, they will find an extended hand from us”. For his part, Aḥmadinejād, renewing the meaning of his predecessor Khātamī’s conciliatory gestures, don’t hesitate to show Koran and Bible in his hands during his participation in the 2010 UN General Assembly. The following year, Obama will eliminate ʾUsāma bin Lādin in Pakistan, a huge source of concern even for Tehrān to its eastern borders;

A session of the Iranian Parliament in 2008

- Ḥasan Ruhani’s election to Iranian Presidency in 2013. The election of an Islamic democracy’s religious leader follows a few months John Kerry’s arrival to the US Secretary of State, after the disputed time span of Hillary Clinton, whose strong bonds with Jewish lobbies are well known. Once the agreement on the nuclear issue has reached in Vienna in 2015 after 23 months of negotiations, Ruhani puts it this way: “This administration believes in dialogue. I myself headed the very first nuclear negotiating team back in 2003 – when no sanctions had been imposed … The steadfastness, resistance, patience, perseverance and support of the great nation of Iran were indeed key to this victory”. For his part, Kerry tweets: “Agreement is a step away from specter of conflict, towards possibility of peace. This is the good deal we have sought”. This is also thanks to the massively popular Moḥammad Javad Zarif, the Iranian Foreign Minister and Chief nuclear negotiator in talks. In short, Obama-Ruhani and Kerry-Zarif (the latter pictured below), two perfect combinations of diplomacy to a fruitful agreement.

The onus is now on Trump and Tillerson. Who will be the Iranian counterparts? We’ll see soon. But, at this point, there’s no guarantee the course of Ruhani (and the Reformist Front Coordination Council that candidates him) proves to be the most welcome to the most instinctive and responsive part of the population. The outgoing President will likely face fierce opponents, such as: the traditionalist Seyyed Moṣṭafā Āgā Mir-Salim, appointed by the Islamic Coalition Party; the fundamentalist Ḥamīd Baghaei, former Vice President of Iran and Head of Presidential Administration in 2011-13 biennium; Mas‘ūd Zaribafan, from the Society of Devotees of the Islamic Revolution and Head of the powerful Foundation of Martyrs and Veterans Affairs from 2009 to 2013; Alireza Zakani, from the Society for the Adherents of the Path of the Islamic Revolution; and former President Maḥmūd Aḥmadinejād. Within the first four days after registration procedures start, all of them are now officially aspiring applicants, but everything is still bound to an application vetting by the Guardian Council of the Constitution before campaign will start next April 28th.

The onus is now on Trump and Tillerson. Who will be the Iranian counterparts? We’ll see soon. But, at this point, there’s no guarantee the course of Ruhani (and the Reformist Front Coordination Council that candidates him) proves to be the most welcome to the most instinctive and responsive part of the population. The outgoing President will likely face fierce opponents, such as: the traditionalist Seyyed Moṣṭafā Āgā Mir-Salim, appointed by the Islamic Coalition Party; the fundamentalist Ḥamīd Baghaei, former Vice President of Iran and Head of Presidential Administration in 2011-13 biennium; Mas‘ūd Zaribafan, from the Society of Devotees of the Islamic Revolution and Head of the powerful Foundation of Martyrs and Veterans Affairs from 2009 to 2013; Alireza Zakani, from the Society for the Adherents of the Path of the Islamic Revolution; and former President Maḥmūd Aḥmadinejād. Within the first four days after registration procedures start, all of them are now officially aspiring applicants, but everything is still bound to an application vetting by the Guardian Council of the Constitution before campaign will start next April 28th.

By contrast, Āyatollāh ‘Alī Khāmene’i (photo below), the Rahbar with his institutional prerogatives, seems to favour continuity. An ascertainment of it is the attitude of Conservative ‘Alī Larijani, President of Parliament and a long-time advisor to the Supreme Leader, who has decided not to support any fundamentalist applicants opposed to Ruhani’s candidacy!