UKRAINE IN BRICS+? MAYBE, EVENTUALLY…

by Glauco D’Agostino

This article was first published in “Geopolitica. Revistă de Geografie Politică, Geopolitică şi Geostrategie“, Annul XXII, nr. 105 (4/2024), PRINCIPIUL DOMINOLUUI (I), Editura “Top Form”, Asociaţia de Geopolitica Ion Conea, Bucureşti, 2025.

Islamic World Analyzes offers this article with Asia and the BRICS+ as its dominant themes, which were unknown to most attentive European analysts. Understanding geopolitical dynamics does not follow the news, this is true. The determinants of international politics remain unchanged in the long term. Not even Donald Trump’s second term holds any surprises, other than the tones halfway between resentment and vindictive, characteristic of a wounded entity or with a mighty awareness of its decline. Yet, Europe is paying the price, fresh from a searing defeat in Ukraine. Again, nothing new. The vassals pay the price, never the lord. The fault is that they could not look beyond the neighbourhood’s boundaries and engaged in small questions of local power, which the decadent lord at issue guaranteed. The Lord has already understood for some time. He realises the true interlocutor, who is also well equipped, is weaving a network of global relationships that he must deal with; BRICS+ is scary now. Beyond the rhetoric, at least it’s worrying, it’s better to negotiate. It is not a given that Ukraine and its next President will not join the BRICS+, eventually at least…

Abstract

The world designed at the end of the Cold War with the recognition of American unilateralism is now just a memory. Perhaps, the roots of that claim must be sought at the origin, with the first fall of the long-standing Empires after WWI, and in the events following WWII. The 2024 Summit in Kazan welcomed the BRICS+ new member countries, all belonging to an area of great geostrategic interest gravitating around the Gulf and the Red Sea. The opening prospects concern Türkiye and Saudi Arabia. Some of the “Partner States” are located in Central Asia, Eastern Europe and Southeast Asia. Meanwhile, Chinese President Xi Jinping in Kazan hoped for the reform of the global financial architecture. In 2014, the BRICS had already set up a multilateral development bank which many consider an alternative to the International Monetary Fund; and the de-dollarisation policy appeared openly.

President Xi had previously stressed how History can renew itself in the actions of the present and future based on the same virtuous propositions which had animated the Ancient Silk Road, by appealing its symbol-power. On the 700th anniversary of Marco Polo’s death, Xi paid homage to the Venetian traveller. Emulating the sense of his feat, China’s Belt and Road Initiative aims to build a bridge to Central Asia, Europe and Africa, placing at the centre an economic aspect (rather than a geostrategic one) from an anti-protectionist perspective. However, it seems clear, that it tends to connect different cultures and political and social systems.

This is an era of change and we must expect variations in managing the world political order, too, while the U.S.-China contrast recurs as a mantra in any international crisis. Today, some international groups (including the BRICS+) are asking for the sharing of choices and responsibilities into a multilateral order and, above all, more civilised methods in managing nations not only in a warlike key. The Silk Road and Marco Polo symbolically celebrate the events of a thousand-year past based on civilisations that sought each other in physical and intellectual communication.

Keywords: world political order, multilateralism, unilateralism, BRICS+, Kazan, Türkiye, Saudi Arabia, China, Xi Jinping, de-dollarisation, Silk Road, Marco Polo, Belt and Road Initiative.

***

Fig. 2 – BRICS+ Summit 2024: Kazan (Republic of Tatarstan, Russia), October 24th, 2024 (by Sergey Bobylev, Photohost agency, brics-russia2024.ru)

Introduction

The Kazan Declaration “Strengthening Multilateralism for Just Global Development and Security” of October 23rd, 2024 by the BRICS+ countries contains in its constituent paragraphs the fundamental concepts of a new world order very different from the one envisaged at the beginning of this century.[1] Multilateral cooperation for stability and security, economic, financial and social development, and exchanges between peoples, all aimed at justice and democracy, are statements of intent that can sound rhetorical and pompous in an international context. Especially challenging, coming from low-middle-income countries, the Global South, as the World Bank defines them.

This is a reading that equates economic power with political ability. Meanwhile, the BRICS+ countries represent half of the world’s population, 40% of global trade, and the same percentage of crude oil production and exports.[2] Regarding their political ability, in the role of the Western financial community, one would be worried about the proposal reiterated in Kazan about reforming the Bretton Woods Institutions, i.e. the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, both headquartered in Washington.

The world designed at the end of the Cold War is now just a memory in the mind of George Bush Jr., who had read this event as the recognition of the American monopoly in international political and economic power, including determining stabilisation (or destabilisation) of entire areas of the world. But, perhaps, the roots of that claim must be sought at the origin, with the first fall of the long-standing Empires after WWI, and in the events following WWII, starting the progressive replacement of the colonial Empires of Great Britain, France and Portugal by the new dominant coloniser. The rest of the world has the perception that it was invariably about colonisation.

Today, that “rest of the world” is trying to accredit its presence not to replace the domination of a declining monocratic power, but as a legitimate aim for a multilateral management of a world aspiring to new coexistence formulas, without the utopia of eliminating conflicts, but with the awareness that the recognition of confrontation between peers can contribute to the management and settlement of disputes.

Is it a revolution? Some tend to emphasise. This is yet another attempt for some “willing people” who, instead of declaring holy wars like others in the past, gather in an aggregation that is not a military alliance or a political coalition, but an organisation of free international subjects not bound by any treaty limiting their independence. It could contribute to a historical turning point that, beyond contingent facts, is inevitable to face the challenges by rediscovering social sensitivities and new technologies.

The BRICS+ geopolitical challenge

Fig. 4 – BRICS+ Summit 2024: Presidents Putin and Xi (by Ramil Sitdikov, Photohost agency, brics-russia2024.ru)

The 2024 Summit in Kazan, in the Russian Republic of Tatarstan, welcomed the BRICS+ new members. They joined the founding countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) that have named the organisation from their initials since 2010. All granted States (Iran, Ethiopia, Egypt, and the United Arab Emirates) belong to an area of great geostrategic interest gravitating around the Gulf and the Red Sea.

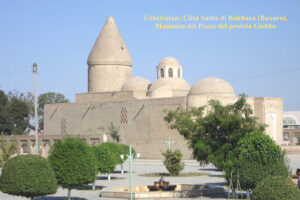

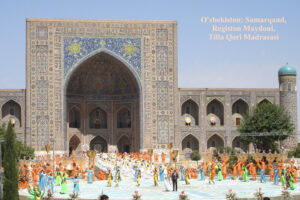

The opening prospects are even more stimulating. Last September, Türkiye formally requested membership, taking the Kremlin’s favour and sending its President Erdoğan to the Kazan Summit. Saudi Arabia has been invited to become a member. Among the “Partner States,” two are located in Central Asia (Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan) and are also members of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO); one in Eastern Europe (Belarus) is also an SCO member; and four of them, recently admitted, are Southeast Asian countries (Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam and Thailand) belonging to ASEAN, with Malaysia taking over the presidency of that regional association in 2025.[3]

These countries are mentioned here because they depict the heart of the BRICS’ Eurasian geopolitics giants. Middle East, Central Asia and South-East Asia are particularly crucial for China in implementing its “Belt and Road Initiative” and upholding its historical role on the continent, evoked with emphasis (but not inappropriately) by the Silk Road’s and Marco Polo’s exploits call. The particular relationship established with some Islamic countries in the Middle East (the recent opening with Iran, Egypt and the Emirates) and the cautious approach with two other Islamic countries in the same area (Türkiye and Saudi Arabia) proposes the same ancient pattern of East-West confrontation, which can be interpreted in a military or shared interests keys. At the moment, Ankara and Riyāḍ act as the gateway to the West, but their geopolitical stance has assigned them to the Western sphere of influence for many decades. Hence, the distrust from Washington and the various European chancelleries to the BRICS+ activism deemed aggressive towards them.

Fig. 5 – China-Turkey Business and Investment Forum: Ürümqi (Xīnjiāng, China) (Source: Outstanding, 2014)

Over the meeting between Putin and Erdoğan on the Kazan Summit sidelines, the Russian President had reassured his interlocutor that the Kremlin had no preclusions to Türkiye’s membership in BRICS+ due to its NATO membership. Many observers underline that economic interests prevail in Ankara’s push towards Moscow, Beijing and New Delhī. And yet, this reading leaves in the shade the geopolitical and cultural role Türkiye has played for centuries in the Black Sea area, the Middle East and all of Central Asia. On the Black Sea, the centuries-old clash with Russia has also put it in communication with the Balkans, the Caucasus and the Muslim-majority internal areas of Russia itself;[4] in the Middle East, the connection with the political-social realities of the imperial legacy goes on; in Central Asia, above all, linguistic, cultural and religious affinity persists, given the common ethnic origin of the respective populations.

The same considerations apply to Saudi Arabia regarding the economic interest in establishing relations with Asian oil-producing countries, recalling the growing Sino-Saudi cooperation[5] and the need to regulate the global supply market with the new OPEC+ countries, first and foremost Russia, but Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, and the Gulf Arab countries.[6] As already observed for Türkiye, Saudi Arabia also plays a leadership role in the religious and cultural field, as a polestar for the entire Sunni Islamic world, where more than half of people live on the Asian continent.

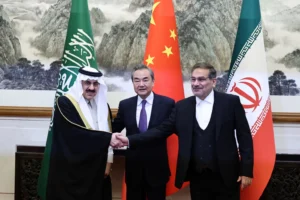

Fig. 7 – Wáng Yì, Chinese Minister of Foreign Affairs, between Musaed bin Moḥammed al-Aiban, Saudi National Security Advisor (l), and ʿAlī Shamkhānī, Iranian Secretary of Supreme National Security Council, Beijing (China), March 10th, 2023 (Source: Bangkok Business)

The other fundamental player in the Middle East, the Islamic Republic of Iran under innumerable sanctions especially from the U.S., the U.K. and the E.U., normalised diplomatic relations with Saudi Arabia in March 2023, despite its geopolitical rivalry since the Kingdom’s birth. Brokered by China, the agreement prepared the entry of the two Gulf countries into the BRICS+ and, perhaps, averted Riyāḍ’s possible accession to the Abraham Accords proposed by the United States during the last months of Trump’s Presidency. The dilemma is which policy in the Middle East the President will follow after his second White House commitment and what the attitude of Saudis and Iranians will be now.[7] But, of course, Elon Musk’s stance will be decisive…

Meanwhile, Chinese President Xi Jinping, now in his third term, spoke in Kazan about the reform of the global financial architecture, also referring to one of the points on the agenda by the Russian Presidency about deepening cooperation in the sector. In this regard, in 2014, the BRICS had already set up a multilateral development bank which many consider an alternative to the International Monetary Fund: the New Development Bank (NDB), which pursues “the purpose of mobilising resources for infrastructure and sustainable development projects in emerging markets and developing countries (EMDCs).”[8] Since 2015, a Beijing-based multilateral credit initiative has also been put beside this entity: the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), which today includes 103 approved Members representing approximately 65% of global GDP.[9]

The policy of pursuing de-dollarisation, i.e. the distancing from the dollar as the currency for international market regulation, had officially appeared in Russian government circles as early as 2022.[10] Since then, the countries that use other currencies (first and foremost the Chinese renmínbì) in mutual commercial and financial transactions have multiplied.[11]

Russian President Vladimir Putin has explicitly indicated some of the measures to contain the dollar’s autocratic power:

- a new system of financial transactions and payments alternative to the SWIFT banking messaging network, given the ban on Russian banks implemented by the U.S., Canada, U.K., and E.U.;[12]

- the creation of a BRICS grain exchange, as a model for other important commodities such as oil, gas and metals.

In this vein, Wolfgang Münchau, former co-founder and editor-in-chief of Financial Times Deutschland, admits that the U.S. wields immeasurable power thanks to the dollar and can impose its will on others. Hence the prerogative to apply sanctions via the financial system. So, a general desire to reduce dependence on the United States is emerging.[13]

Are BRICS+ an anti-Western coalition driven by Sino-Russian interests? Some analysts emphasise the perception of this aggregation at least on the inadequacy of the G7 group of leading economies in solving the problems of emerging countries, eluding the rising realities marking the 21st century.[14] Some others think this is one of the goals of several of its members, not involving India and Brazil.[15] And yet, Putin himself recalled the words of Indian President Narendra Modi when at the Kazan Summit said that the aggregation of the BRICS “it’s not anti-Western; it’s just non-Western.”[16]

Fig. 11 – G20 Summit 2023: New Delhī (India), 9-10 September 2023 (Credits: https://g20.org/summit-and-logos/2023-india/)

Indeed, India, which is already a member of the Russo-Chinese-led Shanghai Cooperation Organisation and is an integral part of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) together with the U.S., Japan and Australia, intends to maintain its geostrategic independence not necessarily tied to Western interests. It has not joined the sanctions against Russia, has opened to the Chinese rénmínbì as oil transactions currency, and benefits from the New Development Bank’s funding for many important projects in the energy and infrastructure sectors.

China and the symbol-power of the Ancient Silk Road

In 2017, President Xi Jinping, speaking at the Opening Ceremony of The Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation, reiterated the contents of the New Type of Security Partnership he had adopted a few months earlier. His speech had the clear intent of connecting the meaning of his 2013 proposal to establish the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road with the main points that constitute the new security strategy: economic integration, building partnerships, multilateralism, rule of law, exchange and military cooperation, dispute resolution. That reasoning also aimed to stress how History can renew itself in the actions of the present and future based on the same virtuous propositions of the past: cooperation, openness to relationships between different civilisations, innovation, learning and mutual benefit. For this was the spirit of the Ancient Silk Road.[17] [18]

If trade was the driving force behind the mobility of goods throughout Eurasia, the fruit was also the intensification of cultural exchanges and the flourishing of art and science in new forms of expression. With its network of original land communication routes, the Silk Road connected China mainly to neighbouring Southeast and Central Asia countries, India and Persia, the Arabian Peninsula and the Mediterranean, yet unlocking East Africa. Around the first century A.D., the main routes started from Luòyáng, in Henan, towards Cháng’ān (today’s Xī’ān) and Gansu, and then split in Dūnhuáng into branches leading to the Tian Shan mountains and the Taklamakan Desert, thus giving access to the territories corresponding to the current states of Central Asia and reaching India and the Roman Empire borders.

With the Yuán Dynasty’s advent in 1271, following the Mongol Empire split in 1259, the Maritime Silk Road took over in importance from land communications, with its trade centred on the port city of Quanzhou, on the Strait of Taiwan.[19] Then, with the Ming Dynasty, the voyages of China’s treasure fleet headed by the Muslim Admiral Zhèng Hé entered the legend of Chinese memory. In seven separate voyages between 1405 and 1433, the Admiral reached Calcutta, the Indian south-western Malabar Coast and Sri Lanka, the Persian island of Hormuz, the Arabian Peninsula and East Africa, setting up a system of interconnected and integrated international relations.[20]

In his 2017 speech mentioned above (CIDCA, 2017), Xi specifically cited some of China’s eminent historical explorers:

- Zhang Qian, a diplomat from the 2nd century B.C. who pioneered travel along the Silk Road and opened the path to knowledge of the Central Asian lands, particularly those along the Hindu Kush mountain range now part of Tajikistan, Pakistan and Afghanistan;

- Dù Huán, a storyteller from the 8th century A.D. who testified to his long presence in the emerging Abbasid Caliphate, which was just at its debut on the international scene;

- And the previously mentioned Zhèng Hé.

But the Chinese President also remembered two no-Chinese figures who had fully entered the Silk Road history:

- The Maghrebi Ibn Battuta, who, a few decades before Zhèng Hé, made journeys from North Africa to Indochina, crossing the Middle East, Central and South Asia, and China, with branches towards Spain and Eastern Africa;[21]

- The Venetian Marco Polo, who, during his life, acquired important imperial offshoot positions in China, so much so that he is still considered today an important part of the history of the Celestial Empire.

China and Marco Polo’s Paradigm

2024 is the year in which the 700th anniversary of Marco Polo’s death, which occurred in Venice at the age of 69, was honoured. Not only Italy but also China remembered him with events of various kinds. Among many, one example is the Exhibition “The Perfect Path: Hangzhou, Marco Polo’s City of Heaven,” hosted by the China Academy of Art with the support of the Venice Biennale and its Historical Archives of Contemporary Arts.[22] During the state visit of Italian President Sergio Mattarella to Beijing last November 8th, Chinese President Xi, recalling the 20th anniversary of the China-Italy comprehensive strategic partnership, paid homage to the Venetian traveller, underlining that “the two sides need to work together to cultivate more envoys like Marco Polo in the new era.”[23]

This statement confirms the view of Prof. Zhang Longxi, who, in his book Mighty Opposites: From Dichotomies to Differences in the Comparative Study of China, counters the “tendency to view China as the conceptual opposite of the West”[24] and assures that “non-antagonistic cultural relations are possible.”[25]

1271, the year in which the young patrician Marco Polo left Venice with his father and uncle for the long journey to the East, meets with two important dates: the proclamation of the Chinese “Great Yuán” Dynasty by Kublai Khan, Genghis Khan’s grandson and Khagan of the Mongols, before assuming the title Emperor of All China eight years later; and the election of Pope Gregory X, who entrusted the three travellers with some letters to deliver to Kublai. In 1275, after three and a half years of vicissitudes, the Polos were received by the new Emperor Yuán in the capital Shàngdū, Inner Mongolia, fulfilling the papal mission. This opened up prospects for the opening of high-profile diplomatic relations between China and some of the most important institutional entities of the West, such as the Papacy and the Republic of Venice.

Marco Polo, also taking advantage of the Khan’s esteem for his father and uncle acquired during a previous trip they made starting from 1260, was immediately invested with diplomatic responsibilities as imperial emissary to India and the Pagan Empire of Burma, and later accomplished missions in the Chinese Tibet Protectorate, the Malay Archipelago, and present-day Sri Lanka and Vietnam.

The most adventurous undertaking, which lasts in the collective memory of all the world’s peoples, was the overland crossing of what in the 19th century would be called the “Silk Road.” Marco Polo passed through many politically unstable areas, mostly after the 1258 fall of the Baġdād Abbasid Caliphate (spreading from Egypt to Afghanistan still at the century dawn), which had been replaced by the Il-Khanate as an expression of the Mongol Empire in the Persian Area. The repercussions also occurred in the rest of the Middle East:

- In Anatolia, since 1256 the Seljuk Sultanate of Rûm was practically subjected to the Mongol Empire, and since 1269 the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia had become tributary to the Mamluk Sultans of the Abbasid Caliphate of Cairo, newly born as the successor of the homonymous Caliphate of Baġdād;

- In Palestine, the Second Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem was continuously besieged by the Mamluks, who from 1265 to 1268 had taken important cities such as Caesarea, Haifa and Jaffa, and destroyed Antioch.

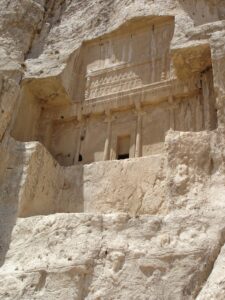

Therefore, Marco Polo’s journey occurred in political and territorial upheavals in which mobility safety was certainly not assured. Starting from Acre, the “Key to Palestine” and capital of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, he continued towards Anatolia, entered the Mongol Il-Khanate, touching the cities of Tabriz, the capital of the State, Alamūt, Baġdād, Baṣra, Hormuz and Yazd, and then advancing on to Kerman and the Southern area of Khorasan. After crossing the Dasht-e Lut Desert, he headed to Samarkand and Turkestan, which were part of the Mongol Khanate of Chagatai and passed independent Badakhshan (today straddling Afghanistan, Tajikistan and China) and the Wakhan, its tributary. He entered the Tarim Basin, where, in the context of civil wars between pretenders to the Mongol Empire throne, a conflict against the Yuán dynasty of Kublai Khan was underway. Finally having entered the Yuán Empire, he passed through Sachion, today Dūnhuáng, Beshbalik, Zhangye and Karakorum, before reaching his destination, the capital Shàngdū.

Fig. 17 – Khorasan (Türkmenistan): State Historical and Cultural Park “Ancient Merv,” Mausoleum of Mu’iz ud-Dīn Aḥmad-e Sanjar (by the author)

Fig. 20 – Transoxiana (Uzbekistan): Samarkand, Dance performance for the 16th Anniversary of Uzbekistan’s Independence from the Soviet Union (by the author)

After 20 years in the Emperor’s service, 17 of which were spent in China, in 1295 Marco Polo returned to Venice and, around the new century onset, made his experiences public through the publication of the book “Il Milione,”[26] written in collaboration with the writer Rustichello da Pisa while he was in prison in Genoa as a consequence of the war between the Ligurian city and La Serenissima.

Certainly, Marco Polo entered fully into the ranks of those travellers who inaugurated a new European era, open by necessity to other peoples and striving towards knowledge and innovation. After all, the Golden Horde Mongols were already present in Europe since they had made Ruthenia and Bulgaria vassal states and had pushed, with their armies mostly composed of Turkic-Asian soldiers, as far as Poland, Romania, Hungary and Dalmatia, that is, to the Venice outskirt. Naturally, their influence was not just geopolitical, but also cultural and customs, which European states had to deal with. However Marco Polo’s extensive contacts with the Mongols in China contributed to increasing trade to the East and also importing technological skills in manufacturing production and artistic ones in architecture and urban planning.

The Belt and Road Initiative, an emblematic legacy of Marco Polo

Emulating the sense of Marco Polo’s feat, China’s Belt and Road Initiative aims to build a bridge to Central Asia, Europe and Africa. As early as 1905, in the Qing era, the building of the first railway began along the route of the Ancient Silk Road, and 50 years later it would lead from the Pacific shores to the Gansu Chinese northwestern province.[27] Today, this railway infrastructure is a section of the New Eurasian Land Bridge Economic Corridor proposed as a gateway to the West, crossing Kazakhstan, Russia, Belarus and Poland.

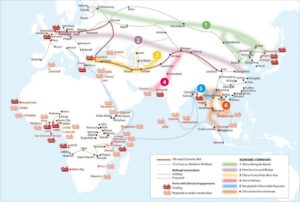

Fig. 23 – Belt and Road Initiative: Economic Corridors and Maritime Silk Road (Source: OECD Business and Finance Outlook 2018)

Another 5 corridors form the terrestrial backbone of the Belt and Road Initiative.[28] Each of these corridors has its raison d’être linked to the facilitation of trade with areas of Beijing economic interest:

- China-Central Asia-West Asia already involves Iran, the Caucasus and Türkiye via rail, also using Istanbul’s Marmaray subsea tunnel in operation for freight traffic since 2019,[29] and it will continue to the Balkans;[30]

- China-Mongolia-Russia will connect Northern Asia with the Baltic Sea in Saint Petersburg;

- China-Pakistan will provide an alternative for the traffic of Chinese energy imports from the Middle East that currently transit through the Strait of Malacca;

- China-Indochina Peninsula will bring the major cities of Southern China closer to the capitals of Southeast Asia such as Hanoi, Vientiane, Phnom Penh, Bangkok, Kuala Lumpur, and Singapore, thus involving the countries of the ASEAN-China Free Trade Area;

- Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar will aim to integrate the economy of the Indian area with that of Chinese Yunnan, also playing a political rapprochement role.

All these land corridors are connected to the ports of the Maritime Silk Road network: apart from Shànghǎi and Hong Kong Chinese harbours, some of them are of particular geopolitical importance: in Southeast Asia, such as those of Hải Phòng, Hồ Chí Minh, Jakarta, Singapore and Kuala Lumpur; on the Indian Ocean, such as Bangkok, Calcutta, Colombo, Malé, Karachi and Mombasa; on the Red Sea, such as Djibouti and Jeddah; on the Mediterranean, such as Haifa, Istanbul, Athens and Valencia. Until December 2023, the Italian ports of Trieste, Genoa, Venice, and Palermo were also candidates to join this important maritime network; at that time, the government authorities in Rome withdrew from the non-binding Memorandum of Understanding signed in March 2019 by the then government in office. The disengagement under pressure from Washington, followed the blocking of Chinese investments in the most important ports of Trieste and Genoa, carried out by a fearful government of national unity in charge between 2021 and 2022.[31]

It is a fact the Belt and Road Initiative has placed the economic aspect at the centre and not the geostrategic one, if anything derivative, that its detractors attribute to it. However, it seems clear, that it tends to connect different cultures and political and social systems. “This methodology embodies traditional Chinese culture and wisdom, which perceives the world in a dialectical, pragmatic, and flexible way,” says Prof. Yuan Li, from the Institute of East Asian Studies (IN-EAST) and the University of Duisburg-Essen (Germany).[32] The expected results can be extrapolated from the March 2015 document Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road,[33] and summarised as follows about the relationship between the participating countries:

- mutual benefit and common security;

- improvement of the region’s infrastructure;

- enhancement of trade and investment facilitation;

- establishment of a network of free trade areas with high standards;

- closer economic ties;

- growth of political trust;

- enhancement of cultural exchanges;

- different civilisations to learn from each other;

- mutual understanding, peace and friendship among people of all countries.[34]

The second point highlights that regional infrastructure improvement can impact poverty reduction and inclusive growth,[35] and the fourth one, from an anti-protectionist perspective, aims at reducing political and economic barriers that prevent trade development between countries.

Final remarks

The long wave of History is a concept that often best interprets the meaning of current events. If the world rightly worries about the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, media communication frequently portrays them as a result of economic conflicts or at most clashes of political-ideological demands. It neglects the method that consciously generates and manages them and above all the historical matrices shaping the great changes in the composition of peoples’ communities. In short, it considers reality immutable in its current determinism, leaving no space for dangerous deviations and subversions. The Nation-State idea, which has its roots in the biblical sources on Ancient Israel’s birth and, as modern formulation, in the 17th-century “Westphalian system”, arises somewhat from that posture.

This is an era of change, no doubt, because of the need to adapt to changing social, cultural and technological conditions. We must also expect variations in managing what is today called the world political order. We cannot call subversion that renewal because its times are always slow and progressive. That renewal is already underway. And yet, this task does not fall to individual nations, already limited by their particular interests, but to the communities they refer to for affinity of some nature. These communities must recognise each other before collaborating to create an accepted behaviour model.

The BRICS+ have become the necessary driver of this renewal because they bridge a leadership void and, in international politics as in nature, the void must be filled. The West is sinking its free-market flag because it no longer guarantees the hegemony of political, economic and financial power over emerging economies, that are proving to be more live and creative. The disproportionate use of sanctions of all kinds and protectionist economic policies take it back to the 17th-century dawn. The situation risks exacerbating with Trump’s advent at the Presidency due to his declared intent to impose tariffs on China (which Washington perceives as its enemy) and the U.S. European allies.

With a pinch of malice, one can say the Chinese strategy of commercial pressure on the economies of Western countries has had its fruits: that world that still refers to the unity of the champions of free market and democracy is dividing into many competing pieces. The BRICS+ and China in particular, notice that they can win this competition campaign in the same field as Western values, i.e., the free market and the rule of law, without opposing them.

The same reading can concern political leadership since the U.S. and its allied circle are in some mess. The continuous undeclared wars against sovereign nations, with the ostentation of an on-and-off anti-terrorism cause, ended up feeding the arrogance of some of its regional proxies in believing it is legitimate to occupy and destabilise entire countries by the messianic pretext of fighting evil. The State of Israel, by claiming the Eretz Yisra’él of biblical memory, is outright upsetting the neighbouring Gaza, the West Bank, Lebanon and Syria with its firepower.

The very situation of uncertainty in Syria makes this reasoning evident. One can give any interpretation to current events, some of which, more than others, smack of short-term news reporting rather than projections on the certainty of lasting stability. The assumptions:

- focus on the conflict of a religious nature, underlining the affiliation of the Syrian contenders to the different Muslim denominations (Shiites, Sunnis, Druze, etc.);

- or emphasise the historical rivalries between neighbouring countries (Türkiye and Iran) for the control of the disputed areas (e.g. Syrian and Iraqi Kurdistan);

- or even place the events within a broader shifting geopolitical context framework, as noted above.

All these readings, each for its part, contribute to defining a possible analytical definition. However, we must also highlight the contradictions inherent in each of them.

The hypothesis of a religious clash, although existing, is shattered by the observation that Iran and its Shiite allies are (or have been) the major defenders of Ḥamās, a Sunni movement rooted in the Muslim Brotherhood. The historical Türkiye-Iran rivalries are not as deep today as those pitting the Ottoman Caliphate against the Qājār’s Persian Empire, because both states oppose Israel’s progressive invasion in the Middle East. The geopolitical assumption seems to be the most plausible and complex because it takes the temporal invariance of interests in that specific area and places them in the broader context of international agreements, by definition as changeable as the rulers’ political visions.

Beyond the tangle of the competing factors, the U.S.-China contrast recurs as a mantra in any international crisis. No one can miss the time’s correspondence in the sudden development of changes. The Damascus fall comes just over a month after the entry into the BRICS+ of important Muslim-majority regional players, as underlined in the introduction. Above all, the full-blown Chinese opening to the Islamic Republic of Iran determined Tel Aviv’s violent attack against Ḥizb Allāh in the previous months and, in a domino game, the weakening of Assad’s power in Syria. In short, it is a work for third parties in which the U.S. has no longer been directly interested in Middle Eastern affairs for at least a decade.

Biden’s America has shown it does not know how to impose an adequate truce, given it has been continuously violated. Trump’s America, with its awe about internal lobbies, could demonstrate Washington’s willingness to enable the fight against arch-enemy Iran further, even at the cost of welcoming the jihādist rule in Syria (with the consequent introduction of the Sharī’a), evidently considered more congruent with Western and Israeli democracy canons than Assad’s secular regime. It also explains the ferocious strafexpedition against the Iranian General Qāsim Sulaimānī, a hero in fighting ISIS. What you don’t do for democracy…

Looking at the long wave of History, the supremacy of Empires has its birth, development, apogee and end. The Macedonia of Alexander the Great, the Empires of Rome and Constantinople, the Muslim Caliphates, and the colonial empires of Great Britain and France have defied the centuries. Yet, after each shattering, the world has been renewed also by taking advantage of their work. Today, what some international groups (including the BRICS+) are asking for is not the end of an Empire, but the sharing of choices and responsibilities into a multilateral order and, above all, the correction to more civilised methods for the management of nations not based only on the use of disturbing war criteria disguised as disputes for the defence of unilaterally interpreted rights.

Finally, the meaning of the evocative hints this writing is connected to is the manifestation of a symbolism generated by their Eastern cultural roots. The Silk Road and Marco Polo symbolically celebrate the events of a thousand-year past based on civilisations that sought each other, scouring physical and intellectual communication routes. Isolationism has never contributed to the civilisation’s growth. Buddhism originated in India but developed in China and Mongolia. Islam was born in Arabia, but its masters and intellectuals feed on Greek wisdom from the Middle East, the Maghreb, Iran, and Southeast Asia. Christianity was born in Palestine but conquered Rome with no weapons and took advantage of Jewish and Zoroastrian thoughts.

The Silk Road and Marco Polo are two emblems of the spirit of knowledge that animates the bold and curious nature, but also images recalling the history of civilisations that have shaped peoples’ way of being. The Silk Road stresses that beyond the eastern borders of the Roman Empire there existed the Arabs, the Persians, the Turks of Central Asia, the Indians and the Chinese, with their troubled and exciting exploits. The figure of Marco Polo is evocative of a period of history, the 13th century, which is the culmination of changes in Eurasia, from the Great Mongol Nation’s birth and its dominance over territories larger than any Empires known until then, to the fall of the centuries-old Abbasid Caliphate of Baġdād, the new China’s rise of the Yuán Dynasty. Yet, those changes contributed to building a new world open to technologies of Eastern origin and preparing a new push towards the explorations by the great European and Chinese navigators.

I conclude with an interesting consideration by Dr Rokplo, former advisor of the special representative of France in the Russian Federation, who summarises a thought that perhaps one can share: “Multipolarity and unipolarity are not only political issues. This is the issue of cultural attitude to reality of different civilizations.”[36]

REFERENCES

ANI. “Putin echoes PM Modi’s stance on BRICS, says ‘it’s not anti-Western; it’s just non-Western’,” October 18th, 2024. https://www.aninews.in/news/world/asia/putin-echoes-pm-modis-stance-on-brics-says-its-not-anti-western-its-just-non-western20241018213921/

Aqilah Norman, Izzah. “Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam and Thailand become partner countries of BRICS,” October 24th, 2024, CAN. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/asia/malaysia-indonesia-vietnam-thailand-brics-asean-global-south-russia-china-4699841.

Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. “About AIIB,” n.d. https://www.aiib.org/en/about-aiib/index.html.

BRICS Russia 2024. “Strengthening Multilateralism for Just Global Development and Security,” October 23rd, 2024. https://cdn.brics-russia2024.ru/upload/docs/Kazan_Declaration_FINAL.pdf?1729693488349783.

Burack, Cristina. “Marco Polo: The travel writer who shocked medieval Europe,” March 18th, 2024, Deutsche Welle. https://www.dw.com/en/marco-polo-the-travel-writer-who-shocked-medieval-europe/a-68540522.

China International Development Cooperation Agency (CIDCA). “Work together to build the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road,” May 14th, 2017. http://en.cidca.gov.cn/2017-05/16/c_260434.htm.

D’Agostino, Glauco. “China and U.S. Race in the Asia-Pacific for the Global Order,” October 30th, 2023, Islamic World Analyzes.

CHINA AND U.S. RACE IN THE ASIA-PACIFIC FOR THE GLOBAL ORDER

D’Agostino, Glauco. “Global Governance: Is Asia’s Time Coming?” Geopolitica. Revistă de Geografie Politică, Geopolitică şi Geostrategie, no. 96-97 (4/2022): (Bucureşti: Top Form), 49-70. https://www.geopolitic.ro/2023/02/global-governance-asias-time-coming/

D’Agostino, Glauco. Tatarstan-Putin: A Crossed Challenge (London, U.K.: Glimmer Publishing, June 2018).

Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Republic of Italy. “Xi Jinping Holds Talks with Italian President Sergio Mattarella,” November 11th, 2024. http://it.china-embassy.gov.cn/ita/sbdt/202411/t20241115_11527028.htm.

Hatipoğlu, Mustafa and Gökmen, Emrah. “First China Railway Express line train reaches Turkey,” November 7th, 2019, Anadolu Agency. https://www.aa.com.tr/en/turkey/first-china-railway-express-line-train-reaches-turkey/163781.

He, Maochun and Zhang, Jibing. “Analysis of the National Strategy of the New Silk Road Economic Belt,” December 23rd, 2013, People’s Tribune. http://www.rmlt.com.cn/2013/1223/203511.shtml.

Hu, Weijia. “China-Saudi Arabia investment cooperation strengthening amid global uncertainties,” November 26th, 2024, Global Times. https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202411/1323824.shtml.

Lau, Lawrence J. “One Belt, One Road (OBOR) and The Asian Infrastructural Investment Bank (AIIB),” Lau Chor Tak Institute of Global Economics and Finance (CUHK), The Chinese University of Hong Kong, December 5th, 2015. https://www.igef.cuhk.edu.hk/igef_media/people/lawrencelau/presentations/english/151205.pdf.

Léautier, Frannie A., Schaefer, Michael and Shen, Wei. “Part I: China’s new Maritime Silk Road: An opportunity for the revival of Africa?” November 13th, 2015, Uongozi Institute.

Part I: China’s new Maritime Silk Road: An opportunity for the revival of Africa?

Li, Yuan. “Belt and Road: A Logic Behind the Myth,” in China’s Belt and Road: a Game Changer? Ed. Alessia Amighini (Milano, Italy: ISPI, Istituto per gli Studi di Politica Internazionale, First edition, 2017), 13-34. doi: 10.19201/ispichinasbelt.

Münchau, Wolfgang. “Non bisogna sottovalutare i Brics+” November 8th, 2024, Corriere della Sera. https://www.corriere.it/opinioni/24_novembre_08/non-bisogna-sottovalutare-i-brics-c207c7dc-410f-434b-b3b0-31b1066b3xlk.shtml?refresh_ce.

Nadalutti, Elisabetta and Rüland, Jürgen. “Hedging ‘Light’: Italy’s Intermezzo With China’s Belt and Road Initiative,” January 13th, 2024, The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2024/01/hedging-light-italys-intermezzo-with-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative/

New Development Bank. “About NDB,” n.d. https://www.ndb.int/about-ndb/

Park, Hyunhee. “The Peak of China’s Long-Distance Maritime Connections with Western Asia During the Mongol Period: Comparison with the Pre-Mongol and Post-Mongol Periods,” in Early Global Interconnectivity across the Indian Ocean World, Volume I, ed. Angela Schottenhammer (Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2019), 53-78. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-97667-9_3.

Patoka, Mariia. “The Great China’s Geopolitical Road,” October 16th, 2024, Svidomi. https://svidomi.in.ua/en/page/the-great-chinas-geopolitical-road.

Patrick, Stewart. “BRICS Expansion, the G20, and the Future of World Order,” October 9th, 2024, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2024/10/brics-summit-emerging-middle-powers-g7-g20?lang=en.

Polo, Marco, Yule, Henry and Cordier, Henri. “The Travels of Marco Polo: The Complete Yule-Cordier Edition, Volume 1,” Courier Corporation, 1993.

President of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Official Website. “Iran, China call for immediate ceasefire in Gaza, Lebanon to reduce regional tensions,” October 24th, 2024. https://president.ir/en/154755.

Reuters. “What is OPEC+ and how does it affect oil prices?” May 24th, 2024. https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/what-is-opec-how-does-it-affect-oil-prices-2024-05-24/

Rice, Dana. “An Overview of China’s Belt and Road Initiative and Its Development Since 2013,” in Securitization and Democracy in Eurasia, eds. A. Mihr, P. Sorbello, and Weiffen (Switzerland: Springer, Cham, 2023), 255-266. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-16659-4_17 B.

Rokplo, O.P. “BRICS+ and History of the World Order: Culturological Thinking of «Tsars of the World»,” in International Likhachov Scientific Conference, BRICS as the New Space for Dialogue Among Cultures and Civilizations, Report 2024 (Санкт-Петербург, Российская Федерация: Санкт-Петербургский Гуманитарный университет профсоюзов, The 22nd International Likhachov Scientific Conference, 12-13 April 2024). https://www.lihachev.ru/chten_eng/2024/reports/Rokplo_OP_en_2024.pdf.

Seneviratne, Dulani and Sun, Yan. “Infrastructure and Income Distribution in ASEAN-5: What are the Links?” February 2013, IMF Working Paper. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2013/wp1341.pdf.

Simkins, Charles. “The Chinese Financial System and Global Economic Stability III – The Silk Road Project,” n.d., Helen Suzman Foundation. https://hsf.org.za/publications/hsf-briefs/the-chinese-financial-system-and-global-economic-stability-iii-the-silk-road-project.

Stronski, Paul and Sokolsky, Richard. “Multipolarity in Practice: Understanding Russia’s Engagement With Regional Institutions” (Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, January 2020). https://carnegieendowment.org/files/Stronski_Sokolsky_Multipolarity_final.pdf.

Wu, Huixin. “Exhibition marks 700 years since death of Marco Polo,” November 18th, 2024, Shine, powered by Shanghai Daily. https://www.shine.cn/feature/art-culture/2411184519/

Xinhua. “Full Text: Vision and actions on jointly building Belt and Road,” April 10th, 2017, Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation. http://2017.beltandroadforum.org/english/n100/2017/0410/c22-45.html.

Xinhua. “Full text: China’s Policies on Asia-Pacific Security Cooperation,” January 11th, 2017, The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. http://english.www.gov.cn/archive/white_paper/2017/01/11/content_281475539078636.htm.

Zhang, Longxi. “Mighty Opposites: From Dichotomies to Differences in the Comparative Study of China,” (California, U.S.A.: Stanford University Press, 1998). doi:10.1515/9781503617315.

***

[1] BRICS Russia 2024, “Strengthening Multilateralism for Just Global Development and Security,” October 23rd, 2024, https://cdn.brics-russia2024.ru/upload/docs/Kazan_Declaration_FINAL.pdf?1729693488349783.

[2] Stewart Patrick, “BRICS Expansion, the G20, and the Future of World Order,” October 9th, 2024, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2024/10/brics-summit-emerging-middle-powers-g7-g20?lang=en.

[3] Izzah Aqilah Norman, “Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam and Thailand become partner countries of BRICS,” October 24th, 2024, CNA, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/asia/malaysia-indonesia-vietnam-thailand-brics-asean-global-south-russia-china-4699841.

[4] It is no coincidence that the BRICS+ 2024 Summit was held in the Republic of Tatarstan, a Russian Muslim-majority Turkic land. The choice’s carefulness arises also because 11 out of 23 countries officially involved in various capacities have a Muslim majority. Glauco D’Agostino, Tatarstan-Putin: A Crossed Challenge (London, U.K.: Glimmer Publishing, June 2018).

[5] Hu Weijia, “China-Saudi Arabia investment cooperation strengthening amid global uncertainties,” November 26th, 2024, Global Times, https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202411/1323824.shtml.

[6] OPEC member states’ exports are about 49% of global crude exports and hold about 80% of the world’s proven oil reserves. Reuters, “What is OPEC+ and how does it affect oil prices?” May 24th, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/what-is-opec-how-does-it-affect-oil-prices-2024-05-24/

[7] For his part, Iranian President Mas‘ūd Pezeshkian, present in Kazan, called for strong economic cooperation with Beijing, immediately supported in the bilateral meeting on the Summit sidelines by Chinese President Xi Jinping, who requested Tehrān to promote peace and stability in the region. President of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Official Website, “Iran, China call for immediate ceasefire in Gaza, Lebanon to reduce regional tensions,” October 24th, 2024, https://president.ir/en/154755.

[8] New Development Bank, “About NDB,” n.d., https://www.ndb.int/about-ndb/

[9] Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, “About AIIB,” n.d., https://www.aiib.org/en/about-aiib/index.html.

[10] Glauco D’Agostino, “Global Governance: Is Asia’s Time Coming?” Geopolitica. Revistă de Geografie Politică, Geopolitică şi Geostrategie, no. 96-97 (4/2022): (Bucureşti: Top Form), 49-70, https://www.geopolitic.ro/2023/02/global-governance-asias-time-coming/

[11] Glauco D’Agostino, “China and U.S. Race in the Asia-Pacific for the Global Order,” October 30th, 2023, Islamic World Analyzes, https://www.islamicworld.it/wp/china-and-u-s-race-in-the-asia-pacific-for-the-global-order/

[12] Anton Siluanov, Russian Finance Minister, officially presented this proposal at the Meeting of BRICS Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors, held in Moscow on October 11th, 2024.

[13] Wolfgang Münchau, “Non bisogna sottovalutare i Brics+” November 8th, 2024, Corriere della Sera, https://www.corriere.it/opinioni/24_novembre_08/non-bisogna-sottovalutare-i-brics-c207c7dc-410f-434b-b3b0-31b1066b3xlk.shtml?refresh_ce.

[14] Paul Stronski and Richard Sokolsky, “Multipolarity in Practice: Understanding Russia’s Engagement With Regional Institutions” (Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, January 2020), https://carnegieendowment.org/files/Stronski_Sokolsky_Multipolarity_final.pdf.

[15] Mariia Patoka, “The Great China’s Geopolitical Road,” October 16th, 2024, Svidomi, https://svidomi.in.ua/en/page/the-great-chinas-geopolitical-road.

[16] ANI, “Putin echoes PM Modi’s stance on BRICS, says ‘it’s not anti-Western; it’s just non-Western’,” October 18th, 2024, https://www.aninews.in/news/world/asia/putin-echoes-pm-modis-stance-on-brics-says-its-not-anti-western-its-just-non-western20241018213921/

[17] China International Development Cooperation Agency (CIDCA), “Work together to build the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road,” May 14th, 2017, http://en.cidca.gov.cn/2017-05/16/c_260434.htm.

[18] Xinhua, “Full text: China’s Policies on Asia-Pacific Security Cooperation,” January 11th, 2017, The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, http://english.www.gov.cn/archive/white_paper/2017/01/11/content_281475539078636.htm.

[19] Lawrence J. Lau, “One Belt, One Road (OBOR) and The Asian Infrastructural Investment Bank (AIIB),” Lau Chor Tak Institute of Global Economics and Finance (CUHK), The Chinese University of Hong Kong, December 5th, 2015, https://www.igef.cuhk.edu.hk/igef_media/people/lawrencelau/presentations/english/151205.pdf.

[20] Frannie A. Léautier, Michael Schaefer, and Wei Shen, “Part I: China’s new Maritime Silk Road: An opportunity for the revival of Africa?” November 13th, 2015, Uongozi Institute, https://www.uongozi.go.tz/sw/news/part-i-chinas-new-maritime-silk-road-an-opportunity-for-the-revival-of-africa/

[21] Hyunhee Park, a Korean-born Professor of History at the City University of New York, has nevertheless documented the activity of many travellers from the Muslim world to China, starting from the 9th-10th century A.D. Hyunhee Park, “The Peak of China’s Long-Distance Maritime Connections with Western Asia During the Mongol Period: Comparison with the Pre-Mongol and Post-Mongol Periods,” in Early Global Interconnectivity across the Indian Ocean World, Volume I, ed. Angela Schottenhammer (Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2019), 53-78. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-97667-9_3.

[22] Wu Huixin, “Exhibition marks 700 years since death of Marco Polo,” November 18th, 2024, Shine, powered by Shanghai Daily, https://www.shine.cn/feature/art-culture/2411184519/

[23] Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Republic of Italy, “Xi Jinping Holds Talks with Italian President Sergio Mattarella,” November 11th, 2024, http://it.china-embassy.gov.cn/ita/sbdt/202411/t20241115_11527028.htm.

[24] Longxi Zhang, “Mighty Opposites: From Dichotomies to Differences in the Comparative Study of China,” (California, U.S.A.: Stanford University Press, 1998). doi:10.1515/9781503617315.

[25] Cristina Burack, “Marco Polo: The travel writer who shocked medieval Europe,” March 18th, 2024, Deutsche Welle, https://www.dw.com/en/marco-polo-the-travel-writer-who-shocked-medieval-europe/a-68540522.

[26] Marco Polo, Sir Henry Yule, Henri Cordier, “The Travels of Marco Polo: The Complete Yule-Cordier Edition, Volume 1,” Courier Corporation, 1993.

[27] He Maochun and Zhang Jibing, “Analysis of the National Strategy of the New Silk Road Economic Belt,” December 23rd, 2013, People’s Tribune, http://www.rmlt.com.cn/2013/1223/203511.shtml.

[28] Dana Rice, “An Overview of China’s Belt and Road Initiative and Its Development Since 2013,” in Securitization and Democracy in Eurasia, eds. A. Mihr, P. Sorbello, and Weiffen (Switzerland: Springer, Cham, 2023), 255-266. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-16659-4_17 B.

[29] Mustafa Hatipoğlu and Emrah Gökmen, “First China Railway Express line train reaches Turkey,” November 7th, 2019, Anadolu Agency, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/turkey/first-china-railway-express-line-train-reaches-turkey/163781.

[30] Since 2012, China has led the “Cooperation between China and Central and Eastern European Countries” (the so-called 14+1 formula) to promote business and investment relationships.

[31] Elisabetta Nadalutti and Jürgen Rüland, “Hedging ‘Light’: Italy’s Intermezzo With China’s Belt and Road Initiative,” January 13th, 2024, The Diplomat, https://thediplomat.com/2024/01/hedging-light-italys-intermezzo-with-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative/

[32] Yuan Li, “Belt and Road: A Logic Behind the Myth,” in China’s Belt and Road: a Game Changer? Ed. Alessia Amighini (Milano, Italy: ISPI, Istituto per gli Studi di Politica Internazionale, First edition, 2017), 13-34. doi: 10.19201/ispichinasbelt.

[33] Xinhua, “Full Text: Vision and actions on jointly building Belt and Road,” April 10th, 2017, Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation, http://2017.beltandroadforum.org/english/n100/2017/0410/c22-45.html.

[34] Charles Simkins, “The Chinese Financial System and Global Economic Stability III – The Silk Road Project,” n.d., Helen Suzman Foundation, https://hsf.org.za/publications/hsf-briefs/the-chinese-financial-system-and-global-economic-stability-iii-the-silk-road-project.

[35] Dulani Seneviratne and Yan Sun, “Infrastructure and Income Distribution in ASEAN-5: What are the Links?” February 2013, IMF Working Paper, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2013/wp1341.pdf.

[36] O.P. Rokplo, “BRICS+ and History of the World Order: Culturological Thinking of «Tsars of the World»,” in International Likhachov Scientific Conference, BRICS as the New Space for Dialogue Among Cultures and Civilizations, Report 2024 (Санкт-Петербург, Российская Федерация: Санкт-Петербургский Гуманитарный университет профсоюзов, The 22nd International Likhachov Scientific Conference, 12-13 April 2024). https://www.lihachev.ru/chten_eng/2024/reports/Rokplo_OP_en_2024.pdf.