All travelers reaching Yazd, a town settled in Central Iran between two deserts, can feel the peculiarity of its architectural ambience, shaped in its brick buildings or manufactured with mud and straw mixture, styled to match its harsh climatic conditions and, moreover, enclosed in a historical context, making it one of the oldest towns in the world still in existence: a center of the Ahura Mazdā’s worship, the Supreme Lord of Zoroastrianism (Yazd, in fact, takes its name from the Avestan term Izad, divine), known as Issatis first by the Medes and later by the Greeks, as Darol’ebadeh by the Arabs early in the years following its conquest in 642, its name, however, is bound to the figure of Yazdgard I, the Sasanian Sovereign of the first quarter of the fifth century A.D., when the Mazdean Zoroastrianism had already been the state religion for over two centuries.

The reason why the Yazd historic core has been able to keep intact its urban form and architecture (as well as traditions) lies in its geographical location, away from the successive imperial capitals over time, and marked by its environmental feature, prejudicial to the transit of any armies; all conditions that have preserved it from the war and its resulting destruction. Indeed, these assumptions have historically identified it as a shelter city, for example for refugees from other Persian towns fleeing the 1220-21 Great Mongol invasion, including many artists, intellectuals and scientists: therefore, it also played a major cultural role. As for the rest, it has always had a dominant function as an important trading post on the caravan routes to Central Asia and India.

The urban structure of the Yazd ancient part is distinguished by a compact formal design and a high building concentration, given by its highly variable climatic factors: in summer, a high solar radiation (an average of 300 sunny days per year) and soaring temperatures (with a peak of 45 °C), with a large daily temperature variation; whereas, a dry cold dominates in winter (with a peak of -16 °C). Furthermore, the area suffers from a very low rainfall (and resulting water shortages) and from the presence of dust-laden desert winds. As a result, its shape reduces the surfaces exposed to direct sunlight and the access of desert winds and ensures an easy penetration of the south-western winds, by favoring a good ventilation of its profound courtyards and basements. For this reason, the narrow trails forming the rib of its mobility system follow specific directional pathways, and are sometimes covered, thereby creating outdoor areas protected by the shaded tall walls of the roadside buildings. The use of thick walls made of clay and raw bricks (that is, materials with a low thermal capacity) helps to insulate buildings, by reducing absorption and reflecting sunlight.

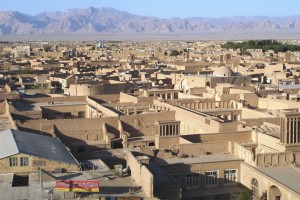

The eye-catching aesthetic design of the town is a result of its structural components (fig. 1 on the left): namely, the bulk of monochrome low-rise buildings, the wounds of separating inner courtyards, the staircases, the balconies diaphragms, the white roof surfaces, the public spaces consisting of narrow streets and sparse small squares designed for walking and cycling traffic; in short, a setting organically composed, with spontaneous characters and homogeneous feature, yet. But the typical elements of this amazing city are its domes and wind towers (fig. 2 on the right), especially the latter, so much so that Yazd (as well as the Iran Crossroads, the Bride of the Desert or even the Desert Pearl) is also called the City of bādgirhā, that is, in fact, the wind towers.

The eye-catching aesthetic design of the town is a result of its structural components (fig. 1 on the left): namely, the bulk of monochrome low-rise buildings, the wounds of separating inner courtyards, the staircases, the balconies diaphragms, the white roof surfaces, the public spaces consisting of narrow streets and sparse small squares designed for walking and cycling traffic; in short, a setting organically composed, with spontaneous characters and homogeneous feature, yet. But the typical elements of this amazing city are its domes and wind towers (fig. 2 on the right), especially the latter, so much so that Yazd (as well as the Iran Crossroads, the Bride of the Desert or even the Desert Pearl) is also called the City of bādgirhā, that is, in fact, the wind towers.

A bādgir (fig. 3 below to the side) is a high mud-brick architectural element, with a rectangular section, and vertical slots designed to capture the favorable winds through their faces appropriately exposed, to naturally cool those winds and channel them into the lower spaces, i.e. the house interiors and basements. This ingenious cooling system is often connected to the water supply network of qanāt, subterranean complex system of canals, some of which are up to 45 km long. The need to find water resources, locally scarce, as already mentioned, had prompted the population since many centuries ago to reach the far mountains in order to channel waterways down, convey them into underground dug out canals, and through a wells web, use its water for productive and civil purposes. Obviously, the groundwater temperature allows that the interaction with wind towers enhances the qanāt potential, even serving the air conditioning and refrigeration, as in the case of Yakh-chāl, the ice wells conceived as domed reservoirs (fig. 3) to be filled in winter for the summer needs.

A bādgir (fig. 3 below to the side) is a high mud-brick architectural element, with a rectangular section, and vertical slots designed to capture the favorable winds through their faces appropriately exposed, to naturally cool those winds and channel them into the lower spaces, i.e. the house interiors and basements. This ingenious cooling system is often connected to the water supply network of qanāt, subterranean complex system of canals, some of which are up to 45 km long. The need to find water resources, locally scarce, as already mentioned, had prompted the population since many centuries ago to reach the far mountains in order to channel waterways down, convey them into underground dug out canals, and through a wells web, use its water for productive and civil purposes. Obviously, the groundwater temperature allows that the interaction with wind towers enhances the qanāt potential, even serving the air conditioning and refrigeration, as in the case of Yakh-chāl, the ice wells conceived as domed reservoirs (fig. 3) to be filled in winter for the summer needs.

Of course, the contemporary Yazd has forgotten bādgirhā as a technological system for new buildings, as well as the urban tissue of new districts is no longer marked with winding streets and cul-de-sacs, useless in the twenty-first century urban functionality: so the city, a renowned textiles industrial hub and home to fiber optics, ceramics, jewelry and clothing manufacturing, unfolds in a checkerboard scheme along broad commercial avenues, and it has rationally located its services, such as the industrial area, established with ecological criteria and away from the residential settlements, and the transport services (airport and railway station), placed in accordance with scales of accessibility, minimizing environmental impact, as well. However, this demand for modernity expressed in the new Yazd has not prevented a “peaceful” coexistence with the traditional Yazd, the one of the mud-brick houses of Qajar era (generally built at the end of ‘800-early ‘900), the one of domes and wind towers, in a combination of original rural settlement and modern business model, linking complex organic pattern and linear geometric scheme.

However, the value and uniqueness of the Yazd historical center, both nationally and internationally recognized, should not make us forget all substantial functional and social problems the area is suffering, by highlighting a need for urban regeneration and consolidation of social relations: in the former case we refer to urban renewal, building restoration and technological innovation; in the latter, we are speaking about an amalgamation between the indigenous and immigrant population (particularly refugees from Afghanistan and Iraq) to be adopted especially in relation to the common awareness of benefiting from a great historical heritage. This is also because the fragile structural configuration of the old town, already fatigued, risks tearing under the burden of immigration from rural areas, which overloads the settlement capacity.

In particular, the major problems are induced by:

- irrationality of the land structure, with many residential lots devoid of an outlet on the road;

- dimensional and technological insufficiency of the road network, which hinders even the proper execution of construction works;

- lack of parking areas, now essential to the achieved level of motorization;

- antiseismic unfitness, both in physical structures of buildings, and in civil protection operations subsequent to an eventual destructive earthquake, unfortunately not unlikely: the confirmation is the total destruction of the nearby ancient town of Bam after the 2003 earthquake;

- inadequate facilities of primary (water, electricity, gas, telephones) and secondary urbanization (schools, health centers), whose levels are lower than the national standards, even in relation to other comparable realities;

- physical and environmental decay, which decreases the area value, also in terms of economic depreciation;

- insufficient level of income for a large part of the population (as opposed to the flaunted welfare of many residents in suburbs), reflecting the owners’ inability to get involved in housing stock upkeeping and upgrading;

- high rate of aged people, testifying the lack of attraction by the center town as a residential and working place for the youngest people;

- lack of privacy wherever the access to dwellings forcibly pass across other properties.

Such problems, by and large common to many historical centers, are recorded, in the Yazd case, within a complex whose value is given by its own unitariness, and, thus, a proper resolution is not easily identifiable via operations emptying its identity: it’s a typical dilemma of urban regeneration in historical settings, which requires a balance between functionality and safety demands and the need for protection of aesthetic values and ethical standards.

Nonetheless, Yazd is not lacking in noteworthy architectural and historical individualities that may qualify its artistic esteem. For example:

among the Islamic architectures:

- Kabir Masjed-e Jamé (the Great Friday Mosque) (outset fig. 4), the major architectural city landmark. Erected on the site of a XII century Zoroastrian Fire Temple, it was built between 1324 and 1365, in the heyday of Muzaffarid power, of which Yazd has been the capital since 1319 until its transfer to Shīrāz in 1357. The Great Mosque is a clear evidence of the city efforts to comply with its new institutional role, emphasized by the majestic façade components: the highest entrance īwān of Iran, entirely decorated with mostly blue and turquoise tiles, with patchwork panels and muqarnas; and the two 48 metres-high minarets overlaid on the portal, which are the highest in Iran, as well. A special feature of the Mosque is that the central courtyard give you direct access to the underlying qanāt;

The Amir Jalaleddin Chakhmagh Takiyeh (fig. 5 to the side), a 1426 example of Timurid architecture, devoted to the regional governor in office at that time. A Takiyeh is the Mourning Theater for ‘Āshūrā’ (the 10th day of the month of Muharram), commemorating the massacre of Kerbala in 61 of Hijrah, when Ḥuseyn, 3rd Shi’ite Imām following his father ‘Alī ibn Abū Ṭālib, was murdered. Then, we are within the Shi’ite ambience, and the rituals taking place each year during ‘Āshūrā’ as a sign of collective grieving include performances of sacred dramas in procession, with men dressed in mourning, beating their own breasts at the sound of drums, and afflict their bodies with chains; and the cortege of Nakhl, the palm of ‘Āshūrā’, a canopy of palm wood, in fact, enriched by fabrics and decorations. A Takiyeh is the main appointed place to all this events. As to what of Yazd, although the monument has been often considered just the entrance portal of the Bāzār, its religious function is clear, since it contains a mosque of the same era. Even though its plant and several architectural parts are to be attributed to the Timurid era, its portal, minarets of the mosque and some of the present arches have been added in the early years of the XIX century, then in the Qajar period;

The Amir Jalaleddin Chakhmagh Takiyeh (fig. 5 to the side), a 1426 example of Timurid architecture, devoted to the regional governor in office at that time. A Takiyeh is the Mourning Theater for ‘Āshūrā’ (the 10th day of the month of Muharram), commemorating the massacre of Kerbala in 61 of Hijrah, when Ḥuseyn, 3rd Shi’ite Imām following his father ‘Alī ibn Abū Ṭālib, was murdered. Then, we are within the Shi’ite ambience, and the rituals taking place each year during ‘Āshūrā’ as a sign of collective grieving include performances of sacred dramas in procession, with men dressed in mourning, beating their own breasts at the sound of drums, and afflict their bodies with chains; and the cortege of Nakhl, the palm of ‘Āshūrā’, a canopy of palm wood, in fact, enriched by fabrics and decorations. A Takiyeh is the main appointed place to all this events. As to what of Yazd, although the monument has been often considered just the entrance portal of the Bāzār, its religious function is clear, since it contains a mosque of the same era. Even though its plant and several architectural parts are to be attributed to the Timurid era, its portal, minarets of the mosque and some of the present arches have been added in the early years of the XIX century, then in the Qajar period;- the Mausoleum of the 12 Imām (Maghbareh-ye Davazdah Emām), a Seljuk architecture built in 1038, showing the hallmarks of this style in its octagonal-shaped dome set to squared walls. The mausoleum bears the inscription of the 12 Shi’a Imām, albeit none of them is buried there; the only present burial (with no registration) is Fakhreddin Esfajaroudi’s, one of the local Sheykhs being venerated since the XIV century;

among the Zoroastrian architectures:

Atash Behram (the Temple of Victory Fire) or Gate of Mithra (fig. 6 to the side), which bears witness to the importance of Yazd in the Zoroastrian cult, especially in the pre-Islamic period. Today, precisely in this temple, behind a glass case, the everlasting fire is burning in a brazier, fed by almond and apricot wood (essences rich in oils and, therefore, slow to burn). However, this fire has been alive since 470 A.D. and has been located in Yazd since 1325. This is why Yazd is still attracting Zoroastrian believers from all over the world. The one-storey building repeats the same features of Indian Zoroastrian temples, and in its front view bears the Faravahar’s image, one of the most popular symbols of Zoroastrianism, wearing a ring representing power, that one Ahura Mazdā delivers to the Kings in order to rule. Inside, on the walls, some verses from the collection of the Avestan holy texts, an example of the Zoroastrian calendar, and a depiction of Zaraθuštra, the Persian prophet founder of Zoroastrianism;

Atash Behram (the Temple of Victory Fire) or Gate of Mithra (fig. 6 to the side), which bears witness to the importance of Yazd in the Zoroastrian cult, especially in the pre-Islamic period. Today, precisely in this temple, behind a glass case, the everlasting fire is burning in a brazier, fed by almond and apricot wood (essences rich in oils and, therefore, slow to burn). However, this fire has been alive since 470 A.D. and has been located in Yazd since 1325. This is why Yazd is still attracting Zoroastrian believers from all over the world. The one-storey building repeats the same features of Indian Zoroastrian temples, and in its front view bears the Faravahar’s image, one of the most popular symbols of Zoroastrianism, wearing a ring representing power, that one Ahura Mazdā delivers to the Kings in order to rule. Inside, on the walls, some verses from the collection of the Avestan holy texts, an example of the Zoroastrian calendar, and a depiction of Zaraθuštra, the Persian prophet founder of Zoroastrianism;- Qal’eh-ye Khamushan (the Towers of Silence), over the Safaiyeh hills, where the Zoroastrians were used to burn their dead people, according to an ancient rite envisaging the non-burial, in order not to contaminate the natural elements, the object of their worship. Today, for over 50 years their dead are being buried by government decree, although the Zoroastrians, loyal to their creed, close them in advance in a concrete sarcophagus;

among the military architecture:

- the fortifications made of mud brick and wooden-armored mortars. The first documented bastion is due to ‘Alā ud-Dawla Kakoui, who ruled Yazd in the XI century, but the oldest remaining portion of walls dates back to 1346-47, that is coincident with the period when Yazd, then Muzaffarid capital, restructured, along with its political power, both its urban form and function. Following complete renewal of the southern walls by Tamerlane, who added new barbicans, walls have been added or repaired in subsequent periods. In modern times, large portions of the walls have been demolished, making way for urban expansion.

Beyond these fine examples of architecture, the intrinsic value of the formal complex of traditional Yazd lies in its theoretical conception, that is a designed and programmed city, subsequently poured into its implementation in terms of location, orientation, use of materials, exploitation of local economy. Another meaningful aspect is the composition of the city as regards the progressive transition from a strictly private to an eminently public space, through the full required gradualism to prevent adverse impacts, as well as the flexibility of the housing functions within individual dwellings.

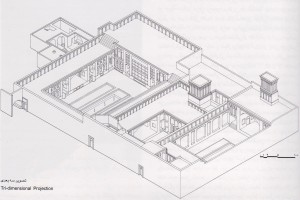

Anyhow, the typical traditional home has geometric and symmetrical shape, two or three floors and is inward-looking, with the openings set around a central open courtyard or even more courtyards (fig. 7 to the side). The main rooms are located on the north-south axis, because from south and south-east cool breezes blow over the summer, and therefore the house wings facing in these directions (tabestan-neshin) are used in this season; conversely in winter for the northern wings (zemestan-neshin), located in such a way as to maximize natural heating provided by the sun. One must also note that winds laden with desert sand come from north and north-west during spring and fall time. The eastern and western wings are used for services (kitchen, bathrooms, pantries, storehouses) and in the summer or winter season the rooms not used for dwelling are temporarily adapted for store rooms, as well. If this seasonal adaptability of living functions affects the house in its horizontal dimension (i.e., among wings according to orientation), in summer that flexibility covers the functions of rooms during different times of day, with a use of various levels from the lowest to the highest of tabestan-neshin as time goes: in practice, the ground floor is mainly frequented in the morning to end at night at the highest level.

Anyhow, the typical traditional home has geometric and symmetrical shape, two or three floors and is inward-looking, with the openings set around a central open courtyard or even more courtyards (fig. 7 to the side). The main rooms are located on the north-south axis, because from south and south-east cool breezes blow over the summer, and therefore the house wings facing in these directions (tabestan-neshin) are used in this season; conversely in winter for the northern wings (zemestan-neshin), located in such a way as to maximize natural heating provided by the sun. One must also note that winds laden with desert sand come from north and north-west during spring and fall time. The eastern and western wings are used for services (kitchen, bathrooms, pantries, storehouses) and in the summer or winter season the rooms not used for dwelling are temporarily adapted for store rooms, as well. If this seasonal adaptability of living functions affects the house in its horizontal dimension (i.e., among wings according to orientation), in summer that flexibility covers the functions of rooms during different times of day, with a use of various levels from the lowest to the highest of tabestan-neshin as time goes: in practice, the ground floor is mainly frequented in the morning to end at night at the highest level.

The central courtyard (fig. 8 to te side) can be used as a rest garden, therefore, with a presence of plants and trees compatible with the desert climate, fountains, and, of course, seats and benches; or, less frequently, with an authentic pool. Sometimes, a second pool placed at a lower level in the same court ensures to raise the standard of coolness afforded by water surfaces. Let’s not forget the cooler effect of wind towers, which, placed in the most suitable position in order to better take advantage of the southern summer winds, lead the natural air conditioning towards the courtyard and interior spaces. But the climatic arrangements do not stop there. Apart from the technological solutions, such as insulating spaces in the walls, consisting of cavities filled with rubble, the traditional home of Yazd provides shaded walls in the courtyard for the hottest hours of the day, sloping roofs and plans to mitigate the impact of sunlight, domed surfaces to minimize the heat storage in the underlying spaces.

The central courtyard (fig. 8 to te side) can be used as a rest garden, therefore, with a presence of plants and trees compatible with the desert climate, fountains, and, of course, seats and benches; or, less frequently, with an authentic pool. Sometimes, a second pool placed at a lower level in the same court ensures to raise the standard of coolness afforded by water surfaces. Let’s not forget the cooler effect of wind towers, which, placed in the most suitable position in order to better take advantage of the southern summer winds, lead the natural air conditioning towards the courtyard and interior spaces. But the climatic arrangements do not stop there. Apart from the technological solutions, such as insulating spaces in the walls, consisting of cavities filled with rubble, the traditional home of Yazd provides shaded walls in the courtyard for the hottest hours of the day, sloping roofs and plans to mitigate the impact of sunlight, domed surfaces to minimize the heat storage in the underlying spaces.

If the inner court is the realm of women, because prevalently a familiar scenery away from prying eyes, a more peripheral setting with outside access is provided for guests, so that they can be accommodated for visits or even for short stays: it’s a semi-private space, a first implementation of progressiveness in relationships, previously mentioned. This gradualism is still detectable in a semi-public space, as it were, formed by hashti, an octagonal structure topped with a dome, located to the side of a crossroad, of a street or a dead end, at the service of a group of houses, and functional upon receipt of guests before being introduced into a private dwelling.

Out of this context, there is a genuine public context, made up of narrow winding streets, sometimes studded with Leng-e Tagh (low bows to deter horse racing) and Sabat (profound arches topped by rooms connecting two buildings), made up of baked bricks, caravanserais, madāris and mosques and adorned with multicolored tiles; but above all, the context of bāzārhā, the domed markets, the heart of the town and pre-eminent meeting places. Inside you can find āb anbār, the underground water tanks connected to the qanāt, accessible through tunnels and stairways: here Yazd really shows off its sense of hospitality, sociability and sustainability, by allowing the wayfarers, maybe in a bargaining with a seller, a free access to its most precious resource, that fresh water conveyed from the distant mountains and protected along its course, without which the town would have found it hard to resist for three thousand years.

This is the special and memorable face of Yazd, the Bride of the Desert. To the sensitivity of men is devolved the choice to preserve it as long as possible like historical witness, but also as a place of a sustainable living and aesthetic grace.