By Glauco D’Agostino

This article was first published in “International Journal of Multicultural and Multireligious Understanding”, Vol. 3, n° 5, Hamburg, Germany, October 2016. Pictures and their references are an addition of islamicworld.it

Abstract

The process of institutional centralization launched by Mr. Putin in a Federation currently counting 85 entities (including the Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol’) is likely to collide with the self-government aspirations, particularly by the 22 republics, because of a documented extensive presence of ethnic minority groups living in their territories. Each of them has its own constitution and legislation. But, according to the Russian Federal Law, all regional heads are to be nominated by Russian President. On the other hand, the Tatar Constitution, aimed to guarantee minority ethnic, religious, or linguistic rights, maintains President of the Republic has to be popularly elected. This situation is creating a framework, if not of legal uncertainty, at least of institutional tensions threatening to escalate unless it would be properly addressed, also due to the specific ethno-religious features of Republics, particularly Tatarstan and Bashkortostan. Both republics are regarded as a model of winning multiethnic states, mainly for the ability to bring together Christians and Muslims to live peacefully.

Moscow concerns give substance to the ghost of never vanished pan-Turkism, since Tatarstan still has relevant independence movements, with a mix of nationalist ideals and religious revival, but all of them with features of peaceful struggle and never extremist. The traditional theological school of law among Muslims of the region is the Ḥanafī one, and the gradual presence of Salafis in the Ural region is regarded by many (though disputed by others) as a source of rampant extremism. The Russian Federation should undertake to recognize and to spread among Tatarstan and Bashkortostan population the value of ethnic and religious coexistence underpinning the Russian Federation concept in the post-Communist era.

Keywords: Tatarstan; Bashkortostan; Putin; centralization; Kazan; nationalism; Ḥanafī Islam

Introduction

To frame Tatarstan and Bashkortostan relations with Russian Federal government means addressing this issue on various levels, from the ethnic and religious to economic and institutional ones. But not only. Because the above mentioned levels may be handled as exclusive affairs of Russian domestic policy. Instead, precisely the historical and cultural peculiarities of both Uralic republics brings, even today, to a topic involving relationships among sovereign states, as the ones between Russia and Turkey are, we will see it. This essay is not intended to focus on the latter cited issue; it doesn’t want to emphasize a prevalence of foreign policy in dealing with aspects pertaining to the political and administrative domain of hierarchies formed within the Federation. But Moscow-Ankara relations are the backdrop for all the subjects, which are covered here in a political-cultural and institutional basis.

Following Putin-Erdoğan meeting of last August, many analyzes have been appropriately carried out about an event that could be defined as a historical, because of the effects this may have on Middle Eastern structure after a lack of understanding on Syrian affaire. However, a small space has been devoted to what that summit may mean for the relationships between Moscow and the Russian Islam, between Moscow and the Islam gravitating around the cultural legacy of Turkish or Ottoman origin. That deal could be defined as a “win-win”, because each party might raise their potential for influence and attraction, as centres of gravity nothing short regionally. Or, that agreement soundness could clash with the difficulties to set up not fully defined century-lasting matters, starting from Crimea and the Caucasus to finish to Afghanistan and Central Asia.

Tatarstan and Bashkortostan, as clear examples of a moving condition, are part of this regional framework. To highlight their particularities right at this moment of rapprochement between the parties does not intend to counter a conciliation process that, if will be resilient to contrast, can only represent stability for all. Instead, it wants to transpose a stakeholders desire to participation and representativeness (Islamic populations, primarily, in addition to state and national interests), so that the required adjustments are not further proved wrong, taking with them all under way efforts of refinement positions at this very delicate moment of international political rebalancing.

Arising Difficulties

Enough to consider the name of the most famous mosque in the Middle Volga-Urals region, Qol Şärif [opening photo 2], which was destroyed in the XVI century and re-opened in Kazan in 2005, to synthesize the strong-arm tactics, fairly good but determined, that both Russian autonomous republics are leading toward Moscow. Especially Tatarstan. Qol Şärif was the Imām of the Mongol Kazan Khanate who died in 1552 while defending his homeland (which at the time also included part of the present Bashkortostan) from Ivan IV the Terrible’s Russia.

But it would be wrong to emphasize remote History for describing a conflict that, rather than religious in nature, has the feel of an institutional dispute in the post-Soviet era. Also because the wound caused by the Khanate fall (followed by forced conversions to Christianity and emigration to the Urals and Siberia[1] was already partially healed by Catherine II the Great, when the Empress of All the Russias enabled the establishment of a Muftī and revoked the prohibition of building mosques. And also because, in contemporary times, Vladimir Putin has been sensitive to the “Islam-state relationship” issue when in October 2013 in Ufa, the capital of Bashkortostan, met with the heads of the Spiritual Board of Muslims (Aron, 2015); and when a few years earlier, in 2005, the year of 1,000th anniversary of Kazan foundation, the President had gone to the Tatar capital to attend celebrations and preside a meeting of the Commonwealth of Independent States.[2]

Of course, the rip made by Tälğät Safa uğlı Tacetdin, the Grand Muftī of Russia, at the end of 2015, just before resigning from his administrative duties, still remains, making apparent the bonds between religious motivations and geo-political placement. While speaking in Ufa at the IV Bashkirs’ Qoroltai (Grand Assembly, in Genghis Khan and Tamerlane the Great’s tradition) soon after the Russian military intervention in Syria, Tacetdin reported what he said to President Putin a few days before: “Vladimir Vladimirovič, perhaps we should do to Syria and Israel what we have done to Crimea? […] We ought to take [them]. May Russia extend to Mecca”.[3]

At internal level, the process of institutional centralization launched by Mr. Putin in a Federation currently counting 85 entities (including the Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol’) is likely to collide with the self-government aspirations, particularly by the 22 republics, because of a documented extensive presence of ethnic minority groups living in their territories. Each of them has its own constitution and legislation. But, according to the Russian Federal Law On the General Principles of the Organization of Local Self-Government in the Russian Federation in its version of 2005, all regional heads are to be nominated by Russian President (Ross, 2007). On the other hand, the Tatar Constitution, aimed to guarantee minority ethnic, religious, or linguistic rights, maintains President of the Republic has to be popularly elected.[4]

This situation is creating a framework, if not of legal uncertainty, at least of institutional tensions threatening to escalate unless it would be properly addressed, also due to the specific ethno-religious features of Republics, particularly Tatarstan and Bashkortostan. We will try to account for all this in the hereafter.

An Overview

Last May, Ufa [three pictures of the city in the side photos 5, 6 and 7] hosted two major events on a level of global industrial business: the “Big Chemistry” International Forum and the XXIV edition of “Gas. Oil. Technologiy” International Exhibition. On 27th, the closing day, also Tatarstan Prime Minister Ildar Khalikov intervened in the plenary session “Government regulation and industrial programs in petrochemical industry”, as part of the Russian Petrochemical Forum.[5] The previous month in Kazan, Tatarstan capital city, about 700 delegates took part in the 11th Venture Fair, where 10 finalist start-ups up to 55 selected from 378 companies won an opportunity to join the international acceleration program in Silicon Valley and Ireland, in addition to a cash prize.[6]

Last May, Ufa [three pictures of the city in the side photos 5, 6 and 7] hosted two major events on a level of global industrial business: the “Big Chemistry” International Forum and the XXIV edition of “Gas. Oil. Technologiy” International Exhibition. On 27th, the closing day, also Tatarstan Prime Minister Ildar Khalikov intervened in the plenary session “Government regulation and industrial programs in petrochemical industry”, as part of the Russian Petrochemical Forum.[5] The previous month in Kazan, Tatarstan capital city, about 700 delegates took part in the 11th Venture Fair, where 10 finalist start-ups up to 55 selected from 378 companies won an opportunity to join the international acceleration program in Silicon Valley and Ireland, in addition to a cash prize.[6]

It’s the new face of these two Russian republics in the second decade of XXI century, typified by an opening of the economic and trading links with foreign countries, especially for Tatarstan, which engages in transactions with more than 120 foreign countries with a turnover of nearly $15 billion in revenue.

The Republic of Tatarstan, along with its wealthy mineral deposits, strong production, highly skilled labour force, has one of the powerful and varied regional economies in Russia (boasting a GDP per capita of more than $23,000 in 2009, the 6th in the Russian Federation), and a solid financial stability, too. Tatarstan, which gives more to the federal budget than it receives, is also deemed as a model for successful economic development, being assisted by an efficient transport system, which will be further enhanced by the implementation of the Moscow-Kazan high-speed railway line, in preparation for 2018 World Football Championships, hosted right in Kazan.[7]

Its key returns come from oil production (about 32 million tons of crude oil is extracted annually in the republic, mainly by its main company Tatneft),[8] manufacturing and chemical processing industries, providing tax incentives for investment and special economic zones to build up a modern technology.[9] Nevertheless, a further face is an environmental problem. Kazan, the millennial capital city with renowned universities (in 2004 Kazan University celebrated its 200th anniversary) and science parks, is quickly becoming one of Russian dominant tech hubs (Zavyalova, 2016). even though its economy is still dependent on oil industry, while suffering the related consequences following treatment processes of a product with particularly harmful health properties from its heavy concentrations of impurities.[10]

Also the Republic of Bashkortostan, a region bordering Siberia, since Soviet times has based its economy on oil (today 43% of its industrial product), adding more recently the chemical and energy systems.[11] Bashneft, its biggest petroleum company producing more than 15 million tons of oil and one of the few oil companies in Russia to have been out of government control until last October,[12] is expanding, as well outside Bashkortostan (in the Middle East) (Hammond, 2013). Bashkir President Rustem Zakievič Khamitov [side photo 11], a 62-years-old engineer, is known for his technocratic and reformist line, with a spotlight on foreign investment.

Also the Republic of Bashkortostan, a region bordering Siberia, since Soviet times has based its economy on oil (today 43% of its industrial product), adding more recently the chemical and energy systems.[11] Bashneft, its biggest petroleum company producing more than 15 million tons of oil and one of the few oil companies in Russia to have been out of government control until last October,[12] is expanding, as well outside Bashkortostan (in the Middle East) (Hammond, 2013). Bashkir President Rustem Zakievič Khamitov [side photo 11], a 62-years-old engineer, is known for his technocratic and reformist line, with a spotlight on foreign investment.

Both republics are regarded as a model of winning multiethnic states, mainly for the ability to bring together Christians and Muslims to live peacefully. Until the USSR downfall, in the Bashkir and Tatar Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republics (respectively established in 1919 and 1920) Islam was mostly repressed, as all religions were: before 1917, there were more than 15,000 mosques in what is now Russia; by 1956, only 94 remained (Malashenko, May 2015). Even the unrealistic attempts by Bolshevik Tatar leader Mirza Khaidargalievič Sultan-Galiev to reconcile Islam and Communism (albeit in the terms advanced by modernist movement and that Orthodox Islam deemed to be blasphemous) had been unsuccessful (D’Agostino, 2010). On the contrary, they had been harshly repressed by Stalin as counterrevolutionaries. It was not until 1991 the building of many mosques and churches could recover or their reconstruction could be performed.

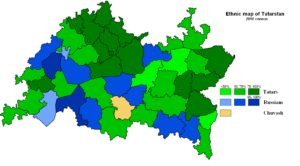

Bashkirs and Tatars, both Turkic Muslim groups, are more than 50% of the region population; 25% is Russian Orthodox, with significant minorities of Christians of other faiths (i.e., Old Ritualists), Jews and believers of traditional religions (i.e., Slavic neo-Pagans, Mari, Udmurtian and Mordvin heathens, Tengriists). In Tatarstan, hosting more than 173 ethnic minorities,[13] traditional Ḥanafī Islam (in its version of “Russian Islam”, as some call it), a variety of Islam blending moderate Islamic teachings with traditional Tatar customs, is practiced widely. The Grand Muftī of Russia is based in Ufa, Bashkortostan capital city and “the capital of Islam in Russia, going back to Catherine the Great”, quoting the head of the Orthodox Church of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Ufa [side photo 12].[14] And if the latter city is regarded as such, Kazan, rather, can officially claim the title of “Third Capital of Russia” (following Moscow and St. Petersburg), since the Federal Service for Intellectual Property (Rospatent) of the Ministry of Economic Development of the Russian Federation has allowed the patent registration in 2009.[15]

Thus, both republics can boast cultural qualifications that live up to their features, from the architectural ones, well symbolized in Lala Tulpan Mosque (Tulip in Bloom) of Ufa [opening photo 3], the Qol Şärif Mosque [opening photo 2, 13 to the side, and 17 below] and Annunciation Cathedral [side photo 14] of Kazan Kremlin [opening photo 1 and 16 below], the XIX-century merchants’ architecture of Elabuga, to those of traditional folk of Sabantuj (plough feast in Turkic languages), national holiday from the republics of the Volga-Ural region honouring the great Tatar poet Ğabdulla Tuqaj. And what this means to Tatarstan is testified by the words current President Rustam Minnikhanov [photo 15 below], a former Tatneft Chairman of Directors’ Board, addressed to his citizens last May 28th: “It is a symbol of awakening the nature, diligence, and the hospitality of our people. Carefully handed down from generation to generation, the holiday has become a true embodiment of our original customs and spiritual heritage”.[16]

Definitely, a cultural, religious, and economic recovery is going through Tatarstan and Bashkortostan people. Obviously, given the peculiarities offered by the post-Soviet times, difficulties and problems, especially for the previous republic, contrast a cautious optimism.

Political Problems

Aside from the aforementioned disputes on constitutional relations between republics and the Federation (that remain the most significant sources of tension of which we will discuss again), the major political problems stem from the following considerations:

- While Tatarstan has had wide autonomy by El’tsin, Putin has forced the primacy of the Russian Federal Constitution and reduced the autonomy of both republics and regions (Keenan, 2013);

- Tatarstan, despite continuing to hold a greater degree of self-rule under a 1990’s pact with the federal government, would like to retain all the prerogatives of a State, including its Republic Presidency;

- Unlike other constituent components of Russia, Tatarstan already has the right to establish official languages in addition to Russian;

- Tatarstan seems to have no intention of breaking relations with Turkey, as Russia has demanded;

- Modern Tatarstan has significant movements calling for independence that are relatively peaceful. Some nationalist movements have appealed to Tatars and other Turkic ethnic groups for establishing an independent State, even though there is no hope to reach a factual sovereignty because of its dependency from Russian-controlled transport networks.[17]

- Parties based on religious identities (as well as regional or ethnic ones) are banned, rejecting most of Muslim population from political leadership and leading to their isolation (Keenan, 2013).

In 1990, even before the Soviet Union collapse, both Tatarstan and then called Bashkirija declared their state sovereignty, rather than independence as some of the federated republics did.[18] After communist state implosion, was primarily Tatarstan to claim its own Islamic cultural legacy, by revaluing Tatar language, since taught in schools and transliterated into Latin characters, following the abandonment of the Arabic characters in favour of Cyrillic ones imposed by Soviet authorities.[19] First Tatar independence movements began to arise, whereas in 1992 Bashkirija was renamed Bashkortostan, with a new reference to kurt, the wolf sacred to the peoples of Turkic origin.

The same year, under the leadership of Mintimer ulı Şəymiyev (its first President), Tatarstan promoted a referendum to confirm its sovereignty, and a large popular majority approved the Constitution, including some of its main principles, as the ability to elect leadership, freedom to promote the Tatar language, and control of its own economy.[20] Nevertheless, the very sovereignty principle would have been restricted by a clarification on Tatarstan membership to the Russian Federation, under the Treaty concerning delegation of authorities and the Agreement On Delimitation of Authority in the Sphere of Foreign Economic Relations, both signed in 1994.[21] The Tatarstan Constitution took note of it just in 2002, by the approval of the related amendments, following the squeeze enforced by President Putin: at that point, Cyrillic became the only official alphabet permitted in Russian provinces and the printing of Tatar in Latin was deemed as a risk to national security.

With this in mind, it’s easier now to understand Putin’s turn about federalism over the previous El’tsin run, mainly due to fear of territorial secessions which, as a paradox, were permitted under Soviet Constitution (even though theoretically), and rather forbidden as an attack to State unity under a democratic system. It’s certainly a heterodox conception of federalism, a “centralized federalism”, if you wish, but certainly not disguised. President himself clarifies it in his book First Person: “Russia was created as a super centralised state. That’s…laid down in its genetic code” (Sakwa, 2002). And, as observed by Tabish Shah from the University of Warwick, UK, even before Putin’s advent in the political arena, in 1999 Evgenij Primakov, as Prime Minister, had said that “restoration of the vertical state power” was necessary to ensure that separatist movements caused by the weakness of the system were “quelled, liquidated, and uprooted” to avoid a complete break up of the Federation.[22]

The regulations mentioned at the beginning of this paper refer to this kind of clearly expressed awareness, including a prerogative by President of the Federation of appointing the Heads of federal entities, which since 2010 the title of President has been no longer recognized to, but only that of “head of the region”, “regional leader” or “chairman of the government”, being no longer elected as in compliance with local constitutions (Keenan, 2013). These constitutions, because Russian federal law takes precedence in Russia’s federal structure, should have been correspondingly amended by 2015. But Tatarstan declined to meet federal constitutional imposition, first by arguing there is no need for any changes (precisely by virtue of republic subjection to Federal State), then rejecting the federal law in 2012.[23]

On the other hand, any Tatar claim seems indisputable, considering the following formulations contained just in the art. 1 of its Constitution: “The Republic of Tatarstan is a democratic constitutional State associated with the Russian Federation by the Constitution of the Russian Federation, the Constitution of the Republic of Tatarstan and the Treaty between the Russian Federation and the Republic of Tatarstan On Delimitation of Jurisdictional Subjects and Mutual Delegation of Powers between the State Bodies of the Russian Federation and the State Bodies of the Republic of Tatarstan, and a subject of the Russian Federation. The sovereignty of the Republic of Tatarstan shall consist in full possession of the State authority (legislative, executive and judicial) beyond the competence of the Russian Federation and powers of the Russian Federation in the sphere of shared competence of the Russian Federation and the Republic of Tatarstan and shall be an inalienable qualitative status of the Republic of Tatarstan”.

This is why Tatarstan keeps to claim not just the title of President for the Head of his executive body,[24] but also the name of State Council for its legislative body and the ability to maintain foreign economic relations under Article III of the Treaty, which states: “The State Bodies of the Russian Federation and the State Bodies of the Republic of Tatarstan jointly are authorised to co-ordinate international and foreign economic relationship”. But Moscow replies, by reiterating accusations against Kazan of entertaining disguised diplomatic relations with several foreign countries, including a few openly at odds with the Russian Federation foreign policy: in the past the allusion was obviously to Turkey, particularly in time of high tension in the theatre of Syrian war; now the situation seems to be better.

Moscow concerns also give substance to the ghost of never vanished pan-Turkism, which had already shocked the Russian Empire since the 80’s of XIX century. At the time, the modernist movement Jadīd (the New, in Arabic), championed by Crimean Tatar publisher İsmail Gaspıralı (known as Gasprinskij) and suspected by Tsarist authorities of relationships with similar movements born in the Ottoman Empire and the British Raj, had since expanded to Central Asia in the early ‘900 and had then raised in the Soviet Union (and after 1991 also in the freed Uzbekistan) (D’Agostino, 2010).

Sure, Tatarstan still has relevant independence movements, but all of them with features of peaceful struggle and never extremist. The Party of Tatar National Independence İttifaq, the first non-communist party in Tatarstan and inspired by the monarchist Liberal Democratic Party Ittifaq al-Muslimin active in the Tsarist Duma, since 1990 has called by its leader, the poetess Fäwziä Bäyrämova, for the recognition of the Tatar state as an international entity, still claiming a supremacy of Islam over nation, and rejecting the ideas of Jadīdism, Sufism and Euro Islam (the latter will be discussed later)(Malashenko, 2015).

The Union of Tatar Youth Azatlyk (Freedom, in Tatar language), established in 1989 under the Soviet regime, openly pursues a pan-Turkist ideal, by organizing rallies under the slogan “Tatarstan isn’t Russia” and “Turkic tribes can turn into one nation only through Islam” (Keenan, 2013). His Chairman, Nail Nabiullin, has given rise to demonstrations in Kazan “for the protection of Muslims’ constitutional rights” and has coordinated in Moscow a presence of activists from Bashkortostan, Chuvashija and the Ul’janovsk region in actions as part of “all-Russia rally against Islamophobia”.

Therefore, a mix of nationalist ideals and religious revival, which, however, does not encroach into radicalism, because its target is a mainly peaceful and substantially integrated population, and then because of the awareness that a full Tatarstan independence is unrealistic, due to its geo-political location and its economic relevance, strategic to Moscow. As a result, all claims are bound to goals of keeping and extending its autonomist status within the Russian Federation.

Religious Problems

A religious component is very much alive within nationalist ambitions. As Alexeij Malashenko, the Chairman of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace Center for Religion, Society, and Security in Moscow, observed in a 2014 essay, “Islam in Russia cannot be completely obedient to the state, because in this country, as elsewhere in the global Muslim Ummah, it is used for expressing social and political protest against the ruling system unable to protect the interests of the Muslims, ensure social justice and build normal relations with society” (Malashenko, 2014). And more: “Because Muslims in Russia are part and parcel of the global Islamic community, with all inherent tendencies… these tendencies are present throughout the Ummah, and neither the North Caucasus, nor even Tatarstan which has existed in a Christian environment for half a millennium can be isolated from them”.[25] In another paper of 2015, he noted that “the Tatars and the Bashkirs seemed so Russified and their Islamic tradition so weak compared to that of the North Caucasus that the very issue of the radicalization of Islam and its politicization in the Volga River basin seemed almost artificial”.[26] Thesis in some way confirmed in the 90’s by Vali Ahmet Sadur, a founder of the Islamic Revival Party, when he says that Russia’s Muslims were “still more focused on ethnic partitions rather than on being part of a united ummah” (Malashenko, 2015).

These references are functional to get in the great public debate about Islam nature in the Urals and Middle Volga region promoted by the authorities in recent years, because they bothered about an alleged infiltration of religious components historically missing this area. In particular, raised issues relate to the following remarks:

- Traditional Islam is still regarded as ritualist and conservative, particularly on the part of young people, who are fascinated by non-traditional Islam;

- A supposed excessive openness of “Ḥanafī traditionalism” (as defined by Valiulla Makhmutovič Iakupov, the deputy Muftī of Tatarstan murdered in 2012) towards Western culture has been refused by Salafists (Bustanov & Kemper, 2013);

- Tatar Salafists hold they are a separate body with respect to Orthodox Russians and Ḥanafī Tatars (Keenan, 2013);

- Some organisations representing “official Islam” say Salafists’ increase can be crushed only by force and no channel of communication should be held with them;

- A dangerous victimization of Salafists is occurring because of an open patronage of one form of Islam over another (Malashenko, 2015);

- Acronyms of Mujāhidīn who refer to fundamentalist experiences coming from the Caucasus have appeared;

- Cells of movements operating for an Islamic Caliphate, which have previously been active almost exclusively in Central Asia, exist in all of Tatarstan and Bashkortostan major cities.

The traditional theological school of law among Muslims of the region is the Ḥanafī one, which was adopted in 922 by Volga Bulgaria rulers[27] in the form as practised in Khwārezm (at that time dominated by the Samanid Kingdom under the formal authority of the ʿAbbāsid Caliphate of Baġdād) and in contrast to the more conservative Shafi’ī school, followed by the Caliph. The choice of all Central Asia Turkic peoples to the Ḥanafī school, which not by chance was the prevailing madhhab in the Ottoman and Mughal Empires, can be ascribed to a Khwārezm influence on Central Asia. Ḥanafī school is based on istiḥsān ijtihād, a personal interpretation built, failing other enlightening sources, on the pursuit of a subjectively defined good, and it requires a Muslim community unanimous consensus (ijmā’) through a pronunciation by the scholars. This helps within limits an adjustment of the Sharī’a rules to non-Arab populations and to changing of the habits over time, and it enables a greater flexibility in judging unorthodox behaviour: therefore, a less restrictive status of women compared to those of other schools, is part, as well, of this view (D’Agostino, 2010).

If Tatar “traditional” way to the Ḥanafī school remains within the limits set by its madhhab, yet, is part of the debate. What’s sure is that an excessively “Western” reading of Islamic affairs is strongly challenged by Salafist groups operating in Tatarstan. Even though, as seen, certain features are inherent to Ḥanafī school, rather than coming from “Western” influences.

The gradual presence of Salafis in the Ural region (such as, on the other hand, in the Caucasus) follows a collapse of the ideological and mobility barriers imposed by the Soviet Union. At that point, an increasing both out and inner migration starts: in the former case, the phenomenon has been caused by the need for religious training, which heads towards the holy places for a suitable period of time, before returning homeland with a cultural background often marked by Wahhābism; in the latter, the one coming from Saudi Arabia and Northern Caucasus, and made up of devout preachers or wealthy religious people committed to finance mosques and madāris construction in the region (Keenan, 2013).

Both circumstances are regarded by many (though disputed by others) as a source of rampant extremism. Ildus Faizov, Chairman of Tatarstan Muslim Religious Board since 2011 to 2013, has been among the main players openly sided against Salafis, he branded as “a movement to impose an alien ideology on Tatarstan’s Muslims” and “imposing their styles of Islam, destroying local traditions and a nationally coordinated system of religious rites”. Shortly after, Faizov began to perform his alarm call, by banning publications from Saudi Arabia, ejecting Imām deemed to be too radical, and requiring to the remaining ones “Ḥanafī traditionalist” programs. All this gave chance to indiscriminate repressions, not only to all radical Salafi and generically defined Wahhābi groups, but also to other Muslim communities like the Deobandi Tablighi Jamā‘at and Nurcu movement with its Sufi Movement of the Ḥanafī Turkish philosopher Fethullah Gülen.

Muftī Farid Salman, Chairman of the Ulema Council of the Russian Association of Islamic Accord, an organisation which can be labelled within the mainstream of the so-called “official Islam”, keeps a similar approach (Ibid). In his opinion, with respect to Wahhābi infiltration in the region, “what we face here does not fit our culture. That is a fierce and severe Bedouin culture. This has nothing to do with Islam and Muslims, but Bedouins”. And, introducing the theme of the cultural religious landmark for people, “the nature of Islam in North Caucasus is Sufism, but Tatars had their own Sufi-culture, as well”.[28] The hint to Sufism is probably a tribute to the efforts made by the deceased Gabdulkhaq Samatov, the Ufa Muslim Spiritual Administration qāḍī for Tatarstan and one of Iakupov’s teachers, to prove the Naqshbandiyya Sufi ṭarīqa in Tatarstan had not completely disappeared in the Soviet era. Anyway, Salman’s speech leads us to infer that he thinks all religious elements extraneous to Tatar popular culture needs to be fought even by force (Bustanov & Kemper, 2013).[29]

Of course, many analysts note this is not the policy implemented by Moscow in the North Caucasian Federal District, where the Government of Presidential Envoy Lieutenant General Sergeij Melikov, the Commander of the joint military force against insurgency in the North Caucasus, actually negotiates with Salafist groups. Certainly, fighting a school of thought, as far as deemed extreme, by demonizing its adherents on behalf of the primacy of a school referred to as “traditional”, has not resulted in considerable aftermath, because it has contributed to an image of Salafis as sacrificial victims of a power system. And even Juldash Jusupov, an ethnologist from the Institute of Humanitarian Research of the Republic of Bashkortostan, says that “Salafism cannot be regarded as a disease suffered by our society. It is an element of the religious development process … Salafism is a religious system for the young … Salafist jamaats [groups, rev.] are more open than we think” (Malashenko, 2015).

Anyway, the Salafist lure is hardly the one to look for legitimacy in the Middle Volga and the Urals. For example, the Mujāhidīn of Tatarstan have collected the legacy of the deceased Rais Mingalejev, who was reportedly closely connected to the insurgency in Dagestan, which, in turn, has replaced the insurgency in Chechnja; both insurgencies had been since 2007 under the command of 1st Emir of the Caucasus Emirate, Doku Khamatovič Umarov, himself murdered, as well.[30] Actually, this alleged threat to regional stability is pretty virtual and essentially propagandistic, as the situation in Tatarstan and Bashkortostan is quiet enough.

Other concerns for the authorities come from the activities of Ḥizb ut-Tahrir (Party of Liberation), part of the international pan-Islamist movement, which had previously operated almost exclusively in Central Asia, and especially in the Ferghana Valley and Taškent (Ibid). This movement has been rooted in Tatarstan not by chance since 1996, when some of its members reached it, mainly ethnic Uzbeks and Tajiks, and among them also the Uzbek Alisher Usmanov, since a teacher in the Kazan “Millennium Islam” madrasa. Ḥizb ut-Tahrir problems started in 2003, when the Russian Supreme Court recognized 15 organizations (including Ḥizb ut-Tahrir) as terrorist organizations. Usmanov was sentenced to nine months in a Russian prison for illegal possession of arms, and, after his extradition to Uzbekistan, was sentenced to eight years. Two years later, the Bashkortostan Supreme Court condemned several party activists from four to nine years of prison.

Such judicial proceedings certainly did not weaken the intensity of Ḥizb ut-Tahrir activities, by then illegal, which it leads not only in Tatarstan and Bashkortostan, but also in the Volga region, Central Russia, and Siberia, by staging blatant public events mainly in major cities [a concerning rally in side photo 21]. For example, the organization in 2009 of the Kurban Bayrami, the Tatar and Turkish name for the Feast of Sacrifice, with so much of Caliphate banners to the streets, has been dramatic. However, apart from these fairly promotional actions, it’s not that Ḥizb ut-Tahrir has stood for subversion or dangerousness against the established order. Instead, the Liberation Party prefers to act on the non-flashy proselytizing level, while easing all Qurʾanic prescriptions over its members, just in order to be more trustworthy and approachable to the eyes of neophytes in the task of uniting Muslim countries in an elective Islamic Caliphate ruled by the Sharī’a Law (Ibid). And besides, this by no means results in support for terrorism, also having regard to the attitude Ḥizb ut-Tahrir has maintained after the September 11th attack, when it suggested in a statement that Muslims should not undertake terrorist actions.

Such judicial proceedings certainly did not weaken the intensity of Ḥizb ut-Tahrir activities, by then illegal, which it leads not only in Tatarstan and Bashkortostan, but also in the Volga region, Central Russia, and Siberia, by staging blatant public events mainly in major cities [a concerning rally in side photo 21]. For example, the organization in 2009 of the Kurban Bayrami, the Tatar and Turkish name for the Feast of Sacrifice, with so much of Caliphate banners to the streets, has been dramatic. However, apart from these fairly promotional actions, it’s not that Ḥizb ut-Tahrir has stood for subversion or dangerousness against the established order. Instead, the Liberation Party prefers to act on the non-flashy proselytizing level, while easing all Qurʾanic prescriptions over its members, just in order to be more trustworthy and approachable to the eyes of neophytes in the task of uniting Muslim countries in an elective Islamic Caliphate ruled by the Sharī’a Law (Ibid). And besides, this by no means results in support for terrorism, also having regard to the attitude Ḥizb ut-Tahrir has maintained after the September 11th attack, when it suggested in a statement that Muslims should not undertake terrorist actions.

Potential Proposals

A preference by the authorities of one over the religious school and their shaking a terrorism danger, actually almost non-existent, don’t favour, as we saw, a resolution of coexistence issues, but of the institutional ones, yet, on the extent of the autonomist powers of the region’s republics (Keenan, 2013). The Russian Federation should undertake to recognize and to spread among Tatarstan and Bashkortostan population the value of ethnic and religious coexistence underpinning the Russian Federation concept in the post-Communist era. And, moreover, also Muslims should be convinced that confessional divisions within them cannot overflow to the point of jeopardizing the social body cohesion advocated by republican constitutions.

The subject is an Islamic affair run holding together forms regarded as “native” and peculiar with other ones deemed as exogenous and alien to local traditions. Least because the former are generally perceived as internal and more compatible with the ethnic integration process and to the Russian and Orthodox religious component, in accordance with Qurʾanic exhortation “O People of the Scripture! Come to a common word as between us and you: that we worship none but God”.[31] But the latter, Salafism to be clear, are still part of the Muslim world in an environment increasingly featured by population mobility.

Definitely, since each constituent is prevented to identify and feel politically represented in a party marked by confessional membership, clarifying relationships and finding any degeneration and extremism get more complicated. In this regard, Gabdulla-khazrat Galiulla, Muftī of the Spiritual Board of Muslims of Tatarstan since 1992 to 1998, says that “in a state with non-Muslim form of government where Muslims make up minority, it is only through political movements that the interests and rights of believers can be defended. It is the only way to influence on the decisions made by authorities”.[32]

Tatarstan-born Ravil’ Ismagilovič Gajnutdinov, the current Grand Muftī of the Spiritual Board of Muslims of the European Region of Russia based in Moscow, by emphasizing the dynamic nature of historical processes, states: “Islam is still evolving. It is possible to modernize the conditions for Islam’s existence in a multi-ethnic and multi-cultural environment without changing its tenets. I support the renewal of Islamic teachings, those aspects that deal with the social sphere, the humanistic spheres of human life. The main tenets are unshakable, of course. They regulate the namaz [the Persian-derived term for ṣalāt, the Muslim prayer, rev.], fasting, zakat, pilgrimages, relations between husband and wife, their property interests and kinship” (Malashenko, 2015).

Rafael’ Sibgatovič Khakimov, Director of the Institute of History at the Academy of Science of Tatarstan, as well, prizes the Islamic reformism, while boosting Euro Islam as the only alternative to religious conservatism and fundamentalism. Deeming this current of thought “as a modern form of Jadidism”, in his publication Euro Islam in the Volga region he says “the key focus of Euro Islam is on ijtihad (a method of critical judgment) for modern interpretation of the Qur’an… Ijtihad brings together the East and the West”.[33] In this, Khakimov seems to be perfectly in accordance with the XIX-century modernist theories of ‘Abdannaṣīr al-Qūrṣāwī and Shihābaddīn al-Marjānī, Jadīdism forerunners and then partially accepted by the aforementioned Iakupov. A relevant difference between Khakimov and Iakupov is that the latter “regarded both the Jadīdīs and the Qadīmīs [their “traditional” opponents] as valuable parts of the Tatar Islamic heritage”, as Alfrid K. Bustanov and Michael Kemper, from the University of Amsterdam, suggest (Bustanov & Kemper, 2013).

Conclusion

The equilibrium of the positions still remains in the hands of republican institutions and the Kremlin, which will succeed in pointing out a road balancing ethno-religious visions, if they actually see the value at stake: the regional social stability, but also the stimulation of a civil awareness open to building a complex and multifaceted statehood that may give space to all cultural expressions and customs in the area. And of course also to the organizational arrangements of local governments.

President Putin, beyond his centralist tendencies which earned him the mocking title (or rather flattering?) of Tsar, seems to have partially understood it. And he proved it during the meeting with the heads of the Spiritual Board of Muslims in October 2013 in Ufa, we have already mentioned in the opening. Recovering remarks reported in the book Putin’s Russia, edited by Leon Aron in 2015, three points seem to emerge from President’s analysis (Aron, 2015):

- The socialization of Islam was the “evolution of the traditional Muslim way of life, thinking and views in accordance with the modern social reality as opposed to the ideology of the radicals”;

- Political Islam “is not necessarily negative”, which would imply a legitimacy recognition of religion involvement in politics;

- Putin’s invitation to Russian Muslim leaders for contributing to “social adaptation of those who come to Russia to live and work” and who are also Muslims, tries to enlist the Russian Muslim community to influence the migrants.

It looks like a persuasive search for balance and a significant opening towards an Islamic commitment to building a new relationship with the Kremlin. Tatarstan and Bashkortostan in particular hope it, despite difficulties of political and institutional nature!

[1] Christine Jacobson & Josh Wilson (n.d.). Tatarstan Semiautonomous and Thriving. Retrieved from School of Russian and Asian Studies, http://www.sras.org/tatarstan.

[2] Tatarstan: Capital Kazan Celebrates Its 1,000th Anniversary, ‘Equilibrium Of Cultures’ (August 26, 2005). Retrieved from Unrepresented Nations and People Organization, http://www.unpo.org/article/2899.

[3] В Кремле не поняли идею муфтия о присоединении Израиля и Сирии к России (The Kremlin did not understand the idea of the Muftī on Israel and Syria adhesion to Russia) (November 25, 2015). Retrieved from LƐnta.ru, https://lenta.ru/news/2015/11/25/umor/.

[4] The Constitution of the Republic of Tatarstan, Chapter 2, art. 91.

[5] Tatarstan President’s Press Office (27.05.2016). Tatarstan Prime Minister Ildar Khalikov takes part in Russian petrochemical forum in Ufa. Retrieved from Government of the Republic of Tatarstan, http://prav.tatarstan.ru/eng/index.htm/news/655965.htm.

[6] Results of the Kazan Venture Fair: 10 startups were selected for the international accelerator (25.05.2016). Retrieved from 16th Russian & 11th Kazan Venture Fair, Kazan – April 26-27, 2016, http://www.kazanventurefair.com/show_news_eng/?title=2016_8_12_10_14.

[7] Christine Jacobson & Josh Wilson (n.d.). Tatarstan Semiautonomous and Thriving, cit.

[8] International Business Publications (2014). Russia: Tatarstan Republic Regional Investment and Business Guide, Washington, D.C. (USA), section Economy and Development, p. 14.

[9] Tatarstan republic (n.d.). Retrieved from Leonard Boekelman, Global 7 Investment Group, http://global7group.com/tatarstan-republic.

[10] Christine Jacobson & Josh Wilson (n.d.). Tatarstan Semiautonomous and Thriving, cit.

[11] Bashkortostan republic (n.d.). Retrieved from Leonard Boekelman, Global 7 Investment Group, http://www.global7group.com/bashkortostan-republic.

[12] Rosneft signed a deal to buy a controlling stake in Bashneft last October 12th. See Kenneth Rapoza (October 14th, 2016), Russia’s ‘Darth Vader’ Seizes Control Of Gas Company Bashneft, retrieved from Forbes, http://www.forbes.com/sites/kenrapoza/2016/10/14/russias-darth-vader-seizes-control-of-gas-company-bashneft/#5a2ed56d3faf.

[13] Welcome to the Republic of Tatarstan (n.d.). Retrieved from Official Tatarstan, http://tatarstan.ru/eng/about/welcome.htm.

[14] Joseph Hammond (6 December 2013). In Russia’s Oil-Rich Bashkortostan, Site Of The Upcoming BRICS Summit, Terror Threats Undercut Investment Efforts. Retrieved from International Business Times, New York, NY (USA), http://www.ibtimes.com/russias-oil-rich-bashkortostan-site-upcoming-brics-summit-terror-threats-undercut-1496936.

[15] Kazan officially becomes Russia’s Third Capital (03.04.2009). Retrieved from pravda.ru, http://www.pravdareport.com/history/03-04-2009/107354-kazan-0/.

[16] Tatarstan President’s Press Office (28.05.2016). Rustam Minnikhanov: Sabantuy is the symbol of awaking the nature, diligence and hospitality of our people. Retrieved from Official Tatarstan, http://tatarstan.ru/eng/index.htm/news/656154.htm.

[17] Christine Jacobson & Josh Wilson (n.d.). Tatarstan Semiautonomous and Thriving, cit.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ronan Keenan (Summer 2013). Tatarstan: The Battle over Islam in Russia’s Heartland. Retrieved from World Policy Journal, Issue Unchaining Labor, http://www.worldpolicy.org/journal/summer2013/tatarstan-battle-islam-russias-heartland.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Agreement between the Government of the Russian Federation and the Government of the Republic of Tatarstan “On Delimitation of Authority in the Sphere of Foreign Economic Relations”. Retrieved from http://archive.is/6W2E#selection-33.0-35.21. Source: Kazan Federal University (21 December 2012), http://www.kcn.ru/tat_en/tatarstan/agree.htm.

[22] Tabish Shah (n.d.). How Federal is Putin’s Russian Federation? Retrieved from http://www.atlantic-community.org/app/webroot/files/articlepdf/howfederal.pdf. The quotation Shah has done refers to: J. Corwin (18 January 1999), Primakov calls for national unity, RadioFreeEurope / RadioLiberty Newsline, Vol 3, No. 11, part I.

[23] Christine Jacobson & Josh Wilson (n.d.). Tatarstan Semiautonomous and Thriving, cit.

[24] Brian Whitmore (January 14, 2016). What Do Tatarstan And Belarus Have In Common? Retrieved from RadioFreeEurope / RadioLiberty, Prague, Czech Republic, and Washington, D.C. (USA), http://www.rferl.org/a/what-do-tatarstan-and-belarus-have-in-common/27487602.html.

[25] Alexej Malashenko (July/September 2014). Islam in Russia. Retrieved from Russia in Global Affairs, n° 3, Moscow, Russia, http://eng.globalaffairs.ru/number/Islam-in-Russia-17002.

[26] Alexej Malashenko (May 13, 2015). Islamic Challenges to Russia, From the Caucasus to the Volga and the Urals. Retrieved from Carnegie Moscow Center, Moscow, Russia, http://carnegie.ru/2015/05/13/islamic-challenges-to-russia-from-caucasus-to-volga-and-urals-pub-60334.

[27] Christine Jacobson & Josh Wilson (n.d.). Tatarstan Semiautonomous and Thriving, cit.

[28] Both quotations are from the article Farid Salman: What is the Difference between Traditional Islam and Salafiyyah? (n.d.). Retrieved from http://islam.ru/en/content/story/farid-salman-what-difference-between-traditional-islam-and-salafiyyah.

[29] Alfrid K. Bustanov & Michael Kemper (2013). Valiulla Iakupov’s Tatar Islamic Traditionalism. Retrieved from Asiatische Studien / Études Asiatiques, Revue de la Société Suisse – Asie, LXVII · 3, Peter Lang AG, Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften, Bern, Schweiz / Switzerland, http://www.zora.uzh.ch/85101/1/03_KBustanov_MKemper_Z.pdf. See from p. 809 to 835.

[30] Two years of Imarat Kavkaz: jihad spreads over Russia’s south (07 October 2009). Retrieved from Caucasian Knot, http://www.eng.kavkaz-uzel.eu/articles/11635/.

[31] The Holy Qurʾan, Sūra Āl-i-ʿim’rān (The Family of Imrān), āya 64. Translation and commentary by A. Yusuf Ali, Islamic Propagation Centre International, Durban, South Africa.

[32] Azat Khurmatullin, Kazan Russian Islamic University (20 June 2008). Islam and political evolutions in Tatarstan, paper presented at the meeting Russia and Islam: Institutions, Regions and Foreign Policy, University of Edinburgh (UK), Old College. Retrieved from http://www.pol.ed.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/28682/Islam_and_political_evolutions_in_Tatarstan.pdf. See § Politicization of Islam in Tatarstan: does it make any sense?.

[33] Rafael Khakimov (n.d.). Euro Islam in the Volga region. Retrieved from Kazan Center of Federalism and Public Policy, Tatarstan, Russia, http://www.kazanfed.ru/en/authors/khakimov/publ1/.

References

- Aron, Leon (May 2015). Putin’s Russia, American Enterprise Institute, Washington, D.C. (USA).

- Bashkortostan republic (n.d.). Retrieved from Leonard Boekelman, Global 7 Investment Group, http://www.global7group.com/bashkortostan-republic.

- Bashneft (2012). Nature of Progress, Annual Report Joint Stock Oil Company. Retrieved from http://www.bashneft.com/files/iblock/3fd/md_eng_web.pdf.

- Business Information Agency, Inc. (2007). Business Profile of the Bashkortostan Republic of Russia, The PlanetInform International Analytical Yearbooks, Arlington, VA (USA).

- Bustanov, Alfrid K. & Kemper, Michael (2013). Valiulla Iakupov’s Tatar Islamic Traditionalism. Retrieved from Asiatische Studien / Études Asiatiques, Revue de la Société Suisse- Asie, LXVII· 3, Peter Lang AG, Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften, Bern, Schweiz/ Switzerland, http://www.zora.uzh.ch/85101/1/03_KBustanov_MKemper_Z.pdf.

- D’Agostino, Glauco (June 2010). Sulle Vie dell’Islam. Percorsi storici orientati tra dottrina, movimentismo politico-religioso e architetture sacre (Historical and Architectural Itineraries across the Muslim Countries), Gangemi, Rome, Italy.

- Farid Salman: What is the Difference between Traditional Islam and Salafiyyah? (n.d.). Retrieved from http://islam.ru/en/content/story/farid-salman-what-difference-between-traditional-islam-and-salafiyyah.

- Hammond, Joseph (6 December 2013). In Russia’s Oil-Rich Bashkortostan, Site Of The Upcoming BRICS Summit, Terror Threats Undercut Investment Efforts. Retrieved from International Business Times, New York, NY (USA), http://www.ibtimes.com/russias-oil-rich-bashkortostan-site-upcoming-brics-summit-terror-threats-undercut-1496936.

- Jacobson, Christine & Wilson, Josh (n.d.). Tatarstan Semiautonomous and Thriving. Retrieved from School of Russian and Asian Studies, http://www.sras.org/tatarstan.

- Karimova, Liliya (May 2010): Islamic Revival in the Post-Soviet Space: Tatar Muslim Women’s Identities in the Central Russian Republic of Tatarstan, IREX, Washington, D.C. (USA).

- Keenan, Ronan (Summer 2013). Tatarstan: The Battle over Islam in Russia’s Heartland. Retrieved from World Policy Journal, Issue Unchaining Labor, http://www.worldpolicy.org/journal/summer2013/tatarstan-battle-islam-russias-heartland.

- Khakimov, Rafael (n.d.). Euro Islam in the Volga region. Retrieved from Kazan Center of Federalism and Public Policy, Tatarstan, Russia, http://www.kazanfed.ru/en/authors/khakimov/publ1.

- Malashenko, Alexej (July/September 2014). Islam in Russia. Retrieved from Russia in Global Affairs, n° 3, Moscow, Russia, http://eng.globalaffairs.ru/number/Islam-in-Russia-17002.

- Malashenko, Alexej (May 13, 2015). Islamic Challenges to Russia, From the Caucasus to the Volga and the Urals. Retrieved from Carnegie Moscow Center, Moscow, Russia, http://carnegie.ru/2015/05/13/islamic-challenges-to-russia-from-caucasus-to-volga-and-urals-pub-60334.

- Mandelstam Balzer, Marjorie (November 11, 2009). Religion and Politics in Russia: A Reader, Routledge, London (UK).

- Rapoza, Kenneth (October 14th, 2016), Russia’s ‘Darth Vader’ Seizes Control Of Gas Company Bashneft, retrieved from Forbes, http://www.forbes.com/sites/kenrapoza/2016/10/14/russias-darth-vader-seizes-control-of-gas-company-bashneft/#5a2ed56d3faf.

- Ross, Cameron (April 2007). Municipal Reform in the Russian Federation and Putin’s “Electoral Vertical”, in Demokratizatsiya, The Journal of Post-Soviet Democratization, 15(2), Moskovskiĭ Gosudarstvennyĭ Universitet im. M.V. Lomonosova, Heldref Publications.

- Sakwa, Richard (2002). Russian politics and society, London.

- Shah, Tabish (n.d.). How Federal is Putin’s Russian Federation? Retrieved from http://www.atlantic-community.org/app/webroot/files/articlepdf/howfederal.pdf.

- Tatarstan republic (n.d.). Retrieved from Leonard Boekelman, Global 7 Investment Group, http://global7group.com/tatarstan-republic.

- Tatarstan: Capital Kazan Celebrates Its 1,000th Anniversary, ‘Equilibrium Of Cultures’ (August 26, 2005). Retrieved from Unrepresented Nations and People Organization, http://www.unpo.org/article/2899.

- Whitmore, Brian (January 14, 2016). What Do Tatarstan And Belarus Have In Common? Retrieved from RadioFreeEurope/ RadioLiberty, Prague, Czech Republic, and Washington, D.C.(USA), http://www.rferl.org/a/what-do-tatarstan-and-belarus-have-in common/27487602.html.

- Zavyalova, Victoria (May 5, 2016). Tatarstan: Russia’s next innovation hot spot, Retrieved from Russia beyond the Headlines, International multimedia project by Rossiyskaya Gazeta, Moscow, Russia, http://rbth.com/science_and_tech/2016/05/05/tatarstan-russias-next-innovation-hot-spot_590521.

- В Кремле не поняли идею муфтия о присоединении Израиля и Сирии к России (The Kremlin did not understand the idea of the Muftī on Israel and Syria adhesion to Russia) (November 25, 2015). Retrieved from LƐnta.ru, https://lenta.ru/news/2015/11/25/umor.