Secession of South, foreign interferences, new autonomist and separatist pushes, armed conflicts, differences in the Islamic component. Nevertheless, Sudan proves the persistence of its historical presence

by Glauco D’Agostino

![]()

The April 27th re-election of Sudanese President ‘Omar Ḥasan Aḥmad el-Bashir (photo on the side) with 94% of the vote has raised a few criticism from purists of “Western” democracy. Given the past performance, that met 68% of the vote in 2010, some analysts questioned today a “suspect” percentage, without regard South Sudan split, precisely encouraged by the West, has deprived incumbent President of his most aggressive rivals, paving the way for his further five-year term.

The April 27th re-election of Sudanese President ‘Omar Ḥasan Aḥmad el-Bashir (photo on the side) with 94% of the vote has raised a few criticism from purists of “Western” democracy. Given the past performance, that met 68% of the vote in 2010, some analysts questioned today a “suspect” percentage, without regard South Sudan split, precisely encouraged by the West, has deprived incumbent President of his most aggressive rivals, paving the way for his further five-year term.

Of course, the political problem may not be restricted to his victory width, since many countries are ruled by Presidents elected with a huge electoral mandate, to which Western media adopt wavering attitudes, depending on geo-political interests at stake. Just to restrict the observation to the last two years, in the former Soviet republics of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Tadzhikistan and Azerbajdzhan, their respective Presidents Nazarbaev, Karimov, Rakhmon and Aliyev have been elected with 97.8%, 90.4% , 83.1%, and 85% of the votes cast. Last year, Syrian President Baššar al-Asad won with 88.7%, and in Mauritania President Aziz received 82% of votes. Socialist Hage Gottfried Geingob of South West Africa People’s Organization (SWAPO) is President of Namibia with 87% of popular vote, and in Costa Rica Luis Guillermo Solís Rivera, backed by liberal Partido Acción Ciudadana, was elected by 77.8% of voters. Even Algerian President ‘Abdelaziz Bouteflika, another socialist on this list, was re-elected for a fourth term with a percentage of 81.5%, and, finally, the putschist as-Sīsī, which Western chancelleries pragmatically flirt by, got a “very democratic” 96.91%.

Rather, a wiser deepening should be carried out on various levels of analysis, and extended at least to these questions:

1. Complexity of domestic political situation;

2. Islamic nature of the State;

3. Autonomist and separatist thrusts;

4. Political-economic factors of internal conflicts and foreign interferences.

Complexity of domestic political situation

Sudanese internal political situation is marked by the following features:

- a President in office since 1989;

- an Islamist party, al-Mu’tamar al-Waṭanī (National Congress), which dominates beyond the political scene, even the farmers’ unions and the lawyers’ and university students’ associations;

- a parliamentary opposition, consisting of two factions of al-Ḥizb al-Ittihadi ad-Dīmuqrāṭī (Democratic Unionist Party), of Ḥizb al-Umma (Nation Party) and a few independent MPs;

- an ongoing national dialogue process, with no preconceived exclusions (unless who chose to stay out), with the inclusion of non-partisan figures and civil society organizations, and with debates on participation at every level, whether State or Federal ones;

- a front of revolutionary opposition, al-Jabhat ath-Thawriyat as-Sūdān (Sudan Revolutionary Front), founded in 2011 by rebel groups from Darfur, including two factions of Ḥarakat Taḥrīr as-Sūdān (Sudan Liberation Movement) and Ḥarakat al-ʿAdl wa l-Musāwāt (Justice and Equality Movement), and from Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile wilāyat.

This system comes from 1999-2000 changes, as first the National Congress suffered the Popular Congress Party split at the hands of Ḥasan ‘Abd Allāh et-Turabi, then Chairman of Parliament at odds with President Bashir on the extent of presidential powers, and later (after the declaration of a state of emergency and the Parliament dissolution), government decided democratic both presidential and legislative elections. The Democratic Unionist Party and Ḥizb al-Umma decided once more to boycott elections, as they did previously. Thus, in December 2000, President Bashir was re-elected with 86.5% of the vote (down from 75% in 1996), and his National Congress Party winning almost all the seats in the Parliament (355 of 360).

Soon after, Turabi’s Popular Congress Party signed an agreement with the Sudan People’s Liberation Army, a major country guerrilla movement created in 1983, which would cost the rebel theologian three years in jail on a charge of conspiracy. For its part, the National Congress merged in 2005 with the Alliance of Working Peoples’ Forces of former President Jaʿfar Muḥammad an-Numayrī, by enabling the Sudanese Socialist Union founder returning to the political scene, after his 14 years exile in Egypt and a vain attempt to oppose President Bashir in the 2000 elections. This political convergence broke shortly after 2009 Numayrī’s death, by the May Socialist Union (evoking the 1969 “May Revolution”) and later the Sudanese Democratic Socialist Union leaks.

The multifaceted galaxy of opposition forces, composed of a range of acronyms connecting them in different ways (National Consensus Forces, National-Democratic Alliance), shows its fragmentation and a lack of coordination, not only organizationally, but also in terms of operational strategy on how to overthrow government, namely on a peaceful and democratic option, underpinned by some, and on the violent or even military ones, supported by others; and this, spite the 2013 “New Dawn Charter” (al-Fajr al-Jadīd al-Mithaq) join them in a political front, merely featured, however, by the will of separating Islam from the State.

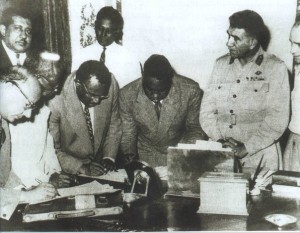

A dispute over the legitimacy of government authority comes from a “source flaw” (even though President Bashir has repeatedly boasted a democratic legitimation): the bloodless June 30th, 1989 seizure of power by the General, supported by a military Council, in the name of “Revolution of National Salvation”. Political parties lay-off, the Sharī’a introduction under decentralized Islamic courts administration in March 1991, the self-proclamation as President in 1993, and the subsequent Military Council dissolution followed. On the other hand, a rule of military regimes in Sudan has covered most of its republican history since independence in 1956 (above picture shows the signature of the Declaration of Independence): first, el-Ferik Ibrāhīm ʿAbbūd, Chairman of the Supreme Council since 1958 to 1964, justified by “the state of degeneration, chaos, and instability of the country”; later, the aforementioned Jaʿfar Muḥammad an-Numayrī since 1969 to 1985, despite a failed communist coup in 1971 and although he was elected President shortly after a plebiscite gave him 98.6% of the vote; still, Field Marshal ʿAbd ar-Raḥmān Swar ad-Dahab, Chairman of the Transitional Military Council between 1985 and 1986, following a coup against Numayrī; finally, el-Bashir.

A dispute over the legitimacy of government authority comes from a “source flaw” (even though President Bashir has repeatedly boasted a democratic legitimation): the bloodless June 30th, 1989 seizure of power by the General, supported by a military Council, in the name of “Revolution of National Salvation”. Political parties lay-off, the Sharī’a introduction under decentralized Islamic courts administration in March 1991, the self-proclamation as President in 1993, and the subsequent Military Council dissolution followed. On the other hand, a rule of military regimes in Sudan has covered most of its republican history since independence in 1956 (above picture shows the signature of the Declaration of Independence): first, el-Ferik Ibrāhīm ʿAbbūd, Chairman of the Supreme Council since 1958 to 1964, justified by “the state of degeneration, chaos, and instability of the country”; later, the aforementioned Jaʿfar Muḥammad an-Numayrī since 1969 to 1985, despite a failed communist coup in 1971 and although he was elected President shortly after a plebiscite gave him 98.6% of the vote; still, Field Marshal ʿAbd ar-Raḥmān Swar ad-Dahab, Chairman of the Transitional Military Council between 1985 and 1986, following a coup against Numayrī; finally, el-Bashir.

Actually, the main el-Bashir’s government oppositions have been historically formed for different reasons:

a. some of them, the parliamentary oppositions, led in the past prominent institutions during the short seasons of formal democracy: the Democratic Unionist Party (under the name of National Unionist Party, yet) managed the transition to independence between 1954 and 1956 by Prime Minister Sayyid Ismāʿīl al-Azharī, who acted as Head of State with the charge of Chairman of the Sovereignty Council between 1965 and 1969; and later, Sayyid Aḥmad ʿAlī al-Mīrġanī has been President of Sudan since 1986 to 1989. Ḥizb al-Umma indicated Sayyid ʿAbdullāh Khalīl as Prime Minister in the years 1956-58; and later, between 1964 and 1969, Sirr al-Khatim al-Khalīfa al-Ḥasan, Muḥammad Aḥmad Mahgoub twice and Sayyid aṣ-Ṣādiq al-Mahdī in the same position; and again the latter between 1986 and 1989;

b. another type of opposition is framed in the internal conflict that occurred in the National Islamic Front (al-Jabha al-Islāmiyya al-Qawmiyya), which is the National Congress forerunner, taking shape as unresolved personal and political clash between President Bashir and Turabi;

c. a further opposition, an irreducible one, has been built up an insurrectional front, subsequent to requests for autonomy or even independence from rebel regions to the Kharṭūm authority, that led to South Sudan secession in 2011, but having left standing violent sedition movements, active mainly in Darfur and South Kordofan.

Needless to say, the parliamentary oppositions are not a big matter of concern to institutional stability, whereas the other forms of contrast to the established state power are deemed by Kharṭūm as dangerous for the very integrity of the State of Sudan, since the reasons of various dissents often add up and weave new scenarios.

Islamic nature of the State

The fracture of the Islamist front under point b. has worsened after South Sudan independence, because since 2012 in Sudan the Front for Islamic Constitution has been working, led by former leader of the Muslim Brotherhood Ḥasan ‘Abd el-Majed, requiring overcoming the 2005 provisional Constitution by the approval of a new Constitution based on Islamic principles, failing which the Front would threaten to depose President Bashir. Turabi’s Popular Congress Party has officially distanced from these positions. Now, when we consider that just Ḥasan et-Turabi (photo below), the fine theologian who studied at the University of Kharṭūm, London and at the Sorbonne in Paris, founded the National Islamic Front in 1976 (after being a Muslim Brotherhood leader since the mid-60’s), and that in 1989 the National Islamic Front had been the ideal engine of the Bashir’s coup, we understand the complexity of today situation, when Bashir, Turabi and the Muslim Brotherhood are found on conflicting positions, or at least as competitors. Moreover, Turabi himself had had complicated relationships with President Numayrī, when, after the General’s coup, first he suffered seven years prison and three years exile in Libya, and then, with the new presidential policy reversing the secular despotism, in 1979 was appointed Attorney General, by acting as Minister of Justice.

Sure, President Bashir has been chasing since 2009 by an arrest warrant of the International Criminal Court (organ that many states, including the US, did not ratify), a measure which underpins the umpteenth attempt to arrest him last June 15th in South Africa at an African Union summit, which President attended; and Turabi, when he was in vogue in the 90’s of last century, gave a very hard time to Washington-Riyāḍ axis, especially through the Popular Arab and Islamic Conference initiatives, which he headed as Secretary-General, and regarded by critics as Islamic extremists and Arab nationalists repository, to the point of inducing the US State Department to put Sudan in 1993 on the list of the “States sponsors of terrorism”. But few among expert observers can doubt that Bashir and, even more so, Turabi have helped to mitigate the Sharī’a rigid interpretation, sought not only by inner hardliners, but also in force in many religious or secular Arab states.

“Islamic government is not total because it is Islam that is a total way of life, and if you reduce it to government, then government would be omnipotent, and that is not Islamic… Law is not the only agency of social control. Moral norms, individual conscience, all these are very important, and they are autonomous” Turabi said. And again: “I personally have views that run against all the orthodox schools of law on the status of women, on the court testimony of non-Muslims, on the law of apostasy”. Bashir has preferred to focus on moderation, too, since the beginning of his first presidency: “We have chosen a moderate way, like the Koran itself, and so the Sharī’a in Sudan will be moderate… Some countries confuse traditions – like the suppression of women – with religion, but tradition is not Islam”.

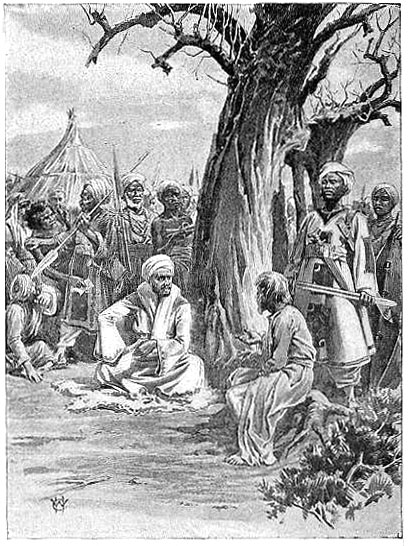

Of course, statements and good intentions do not always correspond to implementation of those principles. But the stances by senior members of ʾAnṣār as-Sunna (Supporters of Tradition), the Salafi movement originated from Saudi Wahhābism, and of Muslim Brotherhood in the 90’s witness to their aversion to Turabi’s line, regarded as a heterodox one, and to the limitations he imposed on the ‘ulamā’ interpretative function: which would confirm the moderate turn having impressed by the new course in Sudan since 1989. By contrast, criticism of Islamist government also comes from the Sufis, mainly from the Khatmiyya Islamic Brotherhood of Muḥammad ’Uthmān al-Mīrġanī (who is also the Democratic Unionist Party leader), and from the Ansari of Sayyid aṣ-Ṣādiq al-Mahdī, their Imām, the Ḥizb al-Umma leader, and a great-grandson of the Mahdī who in 1881 had declared a military jihād against the Anglo-Egyptians (drawing on the side showing him is taken from the book Ten Years’ Captivity in the Mahdi’s Camp, 1882-1892, by Major F. R Wingate, R. A., London, 1892). Distinguishing himself by the puritanical and theocratic legacy of his great-grandfather, aṣ-Ṣādiq claims today a liberal and democratic Sufism, but also the Māhdiyya historical role in having conquered to Islam a permanent place in the Sudanese political body: “Once Islam was in, it never came out. It is impossible to imagine Sudanese politics today without the Islamic component”, he says. Of course, there are those who reproach him for being too elitist and intellectual, and mainly for the failure of leaving sectarian and tribal scopes and familistic domain, that would prevent him from fully performing the alleged role of national political unification.

Of course, statements and good intentions do not always correspond to implementation of those principles. But the stances by senior members of ʾAnṣār as-Sunna (Supporters of Tradition), the Salafi movement originated from Saudi Wahhābism, and of Muslim Brotherhood in the 90’s witness to their aversion to Turabi’s line, regarded as a heterodox one, and to the limitations he imposed on the ‘ulamā’ interpretative function: which would confirm the moderate turn having impressed by the new course in Sudan since 1989. By contrast, criticism of Islamist government also comes from the Sufis, mainly from the Khatmiyya Islamic Brotherhood of Muḥammad ’Uthmān al-Mīrġanī (who is also the Democratic Unionist Party leader), and from the Ansari of Sayyid aṣ-Ṣādiq al-Mahdī, their Imām, the Ḥizb al-Umma leader, and a great-grandson of the Mahdī who in 1881 had declared a military jihād against the Anglo-Egyptians (drawing on the side showing him is taken from the book Ten Years’ Captivity in the Mahdi’s Camp, 1882-1892, by Major F. R Wingate, R. A., London, 1892). Distinguishing himself by the puritanical and theocratic legacy of his great-grandfather, aṣ-Ṣādiq claims today a liberal and democratic Sufism, but also the Māhdiyya historical role in having conquered to Islam a permanent place in the Sudanese political body: “Once Islam was in, it never came out. It is impossible to imagine Sudanese politics today without the Islamic component”, he says. Of course, there are those who reproach him for being too elitist and intellectual, and mainly for the failure of leaving sectarian and tribal scopes and familistic domain, that would prevent him from fully performing the alleged role of national political unification.

Autonomist and separatist thrusts

The other major theme of Sudanese politics is that of internal armed conflicts, which have systematically undermined the institutional stability and the territorial living conditions of the population.

A cursory reading (or, possibly, an interested one) tends to ascribe the conflicting situation only to ethnic or religious reasons. Sudan, before the 2011 secession maiming its territory, was populated by a plethora of ethnic groups, each complying with tribal loyalties and with their own distinctive languages. Certainly, it’s undeniable the north was (and is) inhabited mostly by African population and Arabized Muslims and the south largely by black African Animists converted to Christianity. But this finding is not enough to justify the persistence and ferocity of a civil war that began in 1955, and that, even after the South Sudan independence, continues within the borders of the new state, but also (as mentioned above) in the north, such as in Darfur and Southern Kordofan; and, on the other hand, fact remains that thousands of southern Christians have requested protection and asylum in Kharṭūm and that Bashir’s government has sought alliances with guerrillas in the south, such as the Presbyterian Riek Machar’s, former Vice President of South Sudan.

At the root of conflicts, however, three reasons of ignition are detectable, all of them of a political-economic nature:

- a boost for autonomy towards Kharṭūm predominance on peripheral areas;

- diverging economic interests about exploitation of energy resources and distribution of the resulting revenues;

- a meddling in domestic affairs by international economic, political and strategic interests.

The autonomy issue had previously been addressed in the 1972 Addis Ababa Agreement, when President Numayrī had consented to grant a Constitution integration by the establishment of South Sudan Autonomous Region, which had halted the conflict; but in 1983 this one has been resumed as a result of the unilateral Agreement withdrawal by Numayrī himself. In 2005, the Agreement of Naivasha, in Kenya, had reopened the southern regional autonomy for the following six years, with a self-determination referendum into independence granted later on. With this new deal, the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement, which had signed it, made possible the end of the Second Sudanese Civil War, by stopping hostilities in Southern Kordofan, Blue Nile States and Abyei area, the latter being a still disputed border area between north and south. In return, besides the granted referendum, the insurgents obtained half of oil revenues, and the elected Assembly of South Sudan Autonomous Region the right to decide on the use of Sharī’a in its own territory.

This all accounts for the prevalently political and institutional nature of the historical dispute to Kharṭūm, not only by the southern movements of struggle, but also by those ones from other peripheral areas. And all this had been realized by John Garang de Mabior, the first President of South Sudan Autonomous Region after the 2005 Agreement, who, even though headed the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement, was convincingly opposed to the southern independence and deemed opposition to regime as a means to implement a political revolution, a purpose that could benefit southern people, in the framework of a more united Sudan, the largest State in Africa. With Garang’s death in a plane crash after 21 days of chairmanship, the Movement top officials, who were plotting to establish an independent State, prevailed, and in 2011 picked up the fruits of their efforts by secession, but at the same time betrayed Garang’s intentions, even in setting a truly reformist government: today, President Salva Kiir Mayardit’s regime is not much different from the methods the guerrilla movement ascribed to Bashir. And, as to the independence struggle, this did not end with the achieved southern aim, but has been exported by Liberation Movement northern affiliates to territories of half Sudan, previously mentioned several times, and today still shows no signs of stopping.

Political-economic factors of internal conflicts and foreign interferences

The Naivasha Agreement economic contents highlight the energy issue importance in the onset of the conflict between North and South: today, with the independence attainment, South Sudan has subtracted from the north 75% of the oil resources available to the whole country before the secession, and has cut total revenues of the northern state budget by 35%. This gives rise to an increase in public spending and in the inflation rate, worsening the economic situation of Kharṭūm government. But South Sudan condition is not better than the northern one, as the lack of outlets to the sea forces Djuba government to depend on Kharṭūm’s for transporting oil to Port Sudan, on the Red Sea, via the Sudanese pipeline network, furthermore with serious infrastructural constraints. The finding of large gold reserves in Darfur, however, is useful to explain why the struggle for independence has passed South Sudan borders, up to an armed insurrection in 2004 and an attempt to hoarding what in 2012 accounted for 60% of all Sudanese exports.

No doubt a heavy interference from foreign interests has played a decisive role in Sudanese affairs, up to inducing the country partition, and is playing it to current events in terms of spheres of political and economic influence.

First, the defiant role of Israel is relevant, as it has armed and trained the South Sudan guerrilla movements throughout the First Sudanese Civil War, with a view of weakening Sudan and Arab countries anti-Zionist front, and in accordance with David Ben-Gurion’s policy of Alliance on the Periphery, that was aiming to an alliance with Ethiopia. Despite changes in the internal politics of Sudan, the Israeli approach has never changed, proving geopolitical interests extend beyond any ideological or pragmatic view. Still in 2008, Minister of Internal Security Avi Dichter stated: “We must do so that Sudan be constantly concerned about its internal problems. It’s important Sudan cannot achieve sustainable stability. Important Israel has been keeping the conflict in South Sudan for three decades, and now is keeping it in western Sudan. Avoid Sudan becoming a regional power with influence in Africa and the Arab world”. And again: “There are important forces in the US that, to get South Sudan independence, would welcome a Kosovo-like backed interference in Sudan and Darfur”. Nowadays, with the acquired independence, the Djuba government is grateful to Tel Aviv and repays by showing itself as a faithful tributary to its diplomatic policy and moves in Eastern Africa and Red Sea.

A field of internally displaced persons in Darfur

Not less important, as it’s intuitive, has been the United States challenging function against Sudan. Since 1991 (the year of the fall of Mengistu Haile Mariam’s Communist regime in Ethiopia), the US has aimed at the alliance with Ethiopia of Meles Zenawi Asres (another Marxist-Leninist) and the nationalist Isayas Afewerki’s Eritrean newly formed State, as well as reconfirming its support to Uganda of liberal-nationalist Yoweri Kaguta Museveni, after dropping his communist ideology. In terms of pluralist democracy, we have to underline that Museveni and Afewerki have been still lasting to hold their respective countries, the first for 29 years and the latter for 24, while Zenawi is no longer in their own condition only because his death occurred in 2012. But that’s just an aside, albeit significant.

A key issue, instead, is the Democrat Bill Clinton’s arrival at the White House in 1993 corresponds to the launch of “a Holy Alliance against Kharṭūm”, obviously with the support of the three neighboring countries mentioned above. The fact Washington pointed to overthrow President el-Bashir and his right-hand man et-Turabi in a regional perspective can be clearly inferred from the words of Madeleine Korbel Albright, then US Ambassador to the UN: “The low intensity support to Paul Kagame [then commander of the rebel Tutsi in Rwanda, Author’s Note] will turn with Clinton into a firm engagement to help him take power and, thus, to please Museveni, more than ever the key man of the system that is being set up, and thereby make more consistent the association of Christian African warriors around Garang”. Even after the Sudanese authorities, under pressure from the United States, asking `Usāma bin Lādin to leave the country in 1996, next year President Clinton increased sanctions against Sudan by a decree which stated: “Situation in Sudan represents an exceptional and unusual threat to national security and foreign policy of the United States”.

Therefore, it has been since the 90’s that Washington has drawn the political map of north-eastern Africa, by crystallizing the personal power of some notables in many States, by deconstructing institutions and societies in other ones (see the case of Somalia), and by weakening the role of the only thorn in the side, Sudan, which has been destabilized up to its territorial split. And it does not mean it’s over (see Darfur and Kordofan cases).

Ethnic and religious grounds of fairness? Anti-terrorism? Hard to be claimed in the light of the noticeable US delays in economic competition in the Sudanese market for goods and services. The bugbear has only one name: China, which today is the main economic partner of Sudan, since gained a 40% market share of Sudanese oil investments and despite no longer it has access to the fields in South Sudan. And US strategic target has just one name, as well: Port Sudan, the gateway to the country over the Red Sea, whose services even Djuba cannot give up.

If this analysis proves to be true, north-eastern Africa may prepare for further challenges for the control of international influences on seas, lands and peoples, where once more its generous people are only onlookers in an economic game between distant and more or less aggressive powers, depending on the horizons to which their respective actions are projected.

Faites vos jeux, Messieurs, we are just at the beginning of an economic strategy in a free market. However, an intolerable interference in the internal political affairs of the nations is really unacceptable. And all meant to be in the name of misleading ideological constructs, screens specifically designed for hiding shameful and far more prosaic ambitions!