On the difficult path towards reconciliation

by Glauco D’Agostino

The inauguration of the new Rāmī Ḥamdallāh’s Palestinian government in the West Bank emphasizes that the intent to put an end to internal divisions has not yet produced the desired results. Ḥamās considers the new government illegal and it has forced President Maḥmud ‘Abbās to admit that “this one was supposed to be a government of national unity, but we did not succeed”. The road to building a new State of Palestine on a solid basis of shared goals and subsequent paths suffers a setback, but it could even be strengthened by the Ḥamdallāh’s “transitional” rule in the upcoming months: it will depend on the listening skills and openness the new Prime Minister will provide the country to put the Cairo agreements into effect.

The reconciliation deal between Ḥamās and al-Fataḥ, signed in Egypt last May 14th, had marked a further step of rapprochement between the two Palestinian groups. Following years of contrasts, political détente had begun at the end of 2012, when the Rāmallāh government had twice authorized demonstrations of Ḥamās in the Fataḥ-controlled West Bank. And it was continuing next January 4th in Gaza, the uncontested domain of Ḥamās, during the celebrations for the 48th anniversary of the Fataḥ founding, when both organizations had converged in a joint demonstration, focusing on the shared commitment to the Palestinian national cause.

These happenings had been all effects of at least two crucial events, which have had the power to close the ranks of both antagonistic movements:

- the unwise Israel show of force against Gaza last November, by the offensive ʿAmúd ʿAnán (Pillar of Cloud) and the assassination of Aḥmad al-Jaʿbarī, Deputy Commander of the ‘Izz ad-Dīn al-Qassām Brigades, Ḥamās military wing;

- the UN General Assembly historic vote on November 29th, 2012 (138 votes in favor, 9 against, 41 abstentions) for the Palestine recognition as a “non-member permanent observer State”, which will allow the tormented Middle East country to join any agencies of the United Nations, its bodies such as the Council for Human Rights and the International Court of Justice, and any UN-related organizations such as the International Criminal Court: the citation of the latter clearly concerns the theoretical possibility of a resort to the respective jurisdictions about a hypothetical war crimes committed by Israel or single representatives of the Jewish state.

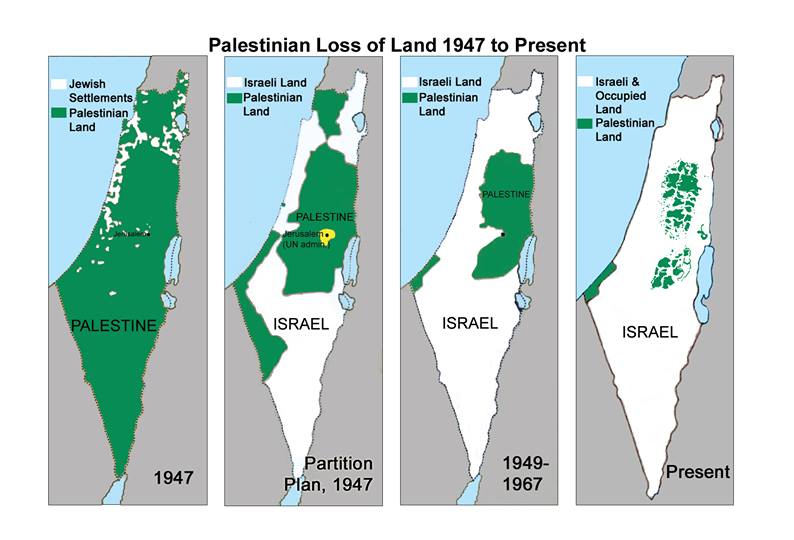

Following the international recognition of the State of Palestine, its territorial and legal framework remains to be actually built for a statehood operation, nowadays suffering because of the extreme fragmentation of its dominated area and because of the stifling protection by the cumbersome Israeli neighbor. But we must acting, as well, for the recovery of a historical, cultural and political identity that can motivate (in terms of regional acceptance) the existence of an individual and identifiable “national” entity. Of course, we must reflect on the word “national”, if we consider that the “nation-state” is a Europe-imported concept, generally alien to the Arab world and introduced by the frantic season of independences from foreign imperialism after the Caliphate fall.

Today, with the opening of many States at aggregations of regional integration (e.g. European Union, African Union, League of Arab States, Gulf Cooperation Council, Union State of Russia and Belarus), even Palestine requires decisions to strengthen ties with its referents in a field of wider cooperation, without which its fragile structural configuration is likely to fail under the blows of anyone interested in preventing its roots in the Middle East.

Therefore, the establishment of a dense relationship networks with natural and historically compatible partners (i.e., the League of Arab States and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation) might benefit the current and future Palestinian leaderships, if they would avoid regarding the Palestinian issue as a solely Palestinians’ problem and, at the same time, if would stress membership in larger communities, such as the Arab and Islamic ones.

The road taken by the Palestinian President ‘Abbās seems right now anxiously seeking internal reconciliation (although he fails to satisfy the Ḥamās political demands) and dialogue with Israel (in continuity with the approach of the Oslo Accords of 1993). At the same time, to achieve these goals, he must face many problems, affecting three substantial policies:

- reconsidering relations with the State of Israel;

- strengthening the inner ties of popular solidarity;

- realignment of the mutual relations among the political components.

About the first point, a balanced stance towards Israel should be taken, being able to keep in mind, on the one hand, the impervious but factual route to a problematic coexistence, however addressed towards a viable peace; on the other hand, by experiencing the feeling of the resistance movements, which express a popular intolerance towards a lack of real political independence and of personal and collective freedom of movement.

In this regard, President ‘Abbās, on the sidelines of the World Economic Forum on the Middle East and North Africa, said last May 25th that “peace with Israel is still possible”, that “we want a just and comprehensive peace” and that “we want two States side by side, living according to international resolutions, the Road Map and the Arab Peace Initiative”. Even Khalid Masha’l, Head of the Ḥamās Political Bureau, said that “disputes with Fataḥ on the available means to fight Israel are shrinking more and more” and added that “Ḥamās is in principle open to negotiations with Israel”. However, claiming to be conducive to the peaceful methods adopted by President Maḥmud ‘Abbās, he also stated that “armed resistance is an integral part of the Movement principles”. Therefore, he shows some availability, but conditional upon a resolution of problems that, it should be noted, for the Palestinian State are called, yet:

– presence of the intolerable “security barrier” in the West Bank, which Palestinians suffer as a ‘barrier of racial segregation”;

– persistence and increase of Jewish illegal colonial settlements;

– fragmented area assigned to the Ramallah government;

– isolation of Gaza, due to the oppressive mobility control of its border crossing points;

– viability of East Jerusalem, under military occupation since 1967, unilaterally annexed in 1980 and illegally proclaimed capital of Israel by the Knesset, despite the 1947 UN General Assembly Resolution 181 had entrusted al-Quds (the Holy City) to a special international regime under UN administration.

As to the second point, you need measures for the appreciation of those civil society sections (e.g. Non-Governmental and Charity Organizations) which are supporting on the ground the communities suffering consequences of daily repression (arrests, raids, demolition of dwelling houses), are providing free social services such as medical, educational and religious care, and are non-violently contrasting the expansion of the foreign occupation enforced by the arbitrary settlements policy.

Regarding the new political relations aimed to social cohesion and inter-institutional loyalty, it was already mentioned the shaky solidarity pact between Ḥamās and Fataḥ as the fundamental axis of the new State of Palestine. But you still have to highlight the moves in this direction by the Movement for Islamic Jihad in Palestine (Harakat al-Jihād al-Islāmī fī Filasṭīn) of Ramaḍān Shallāḥ. Although it had boycotted the 2007 legislative elections and opposed the Ḥamās rule in Gaza, this movement announced last year its involvement in the elections of the National Council of the Palestine Liberation Organization, and last February has encouraged its members to register for the first time as well in the electoral rolls for municipal elections. Of course, there are still innumerable obstacles separating this jihadist organization from its complete acceptance of the PLO role as leader of political-institutional participatory process, at least – said the movement – as long as governments will be the consequence of the Oslo Accords; however, it is remarkable its recognition of the other Palestinian political factions as brothers in the struggle for freedom from the occupation yoke.

The road the Palestinian State needs to cover to achieve a complete internal institutional legitimacy is long, President ‘Abbās knows it. And he also knows that should call at the table of national building up all the stakeholders contributing to its formation. “President urges all country forces and factions to act together speeding up the work, so that he’s able to issue two decrees: one to form a national unity government of independent technocrats, the other one to fix a date for the elections (presidential and legislative)” press sources reported last April 27th. Two weeks earlier the President had accepted the resignation of Salām Fayyāḍ, who had been appointed Prime Minister on June 14th, 2007, without getting the approval of the Palestinian Legislative Council. For this reason, his charge was contested by Ismā’īl Haniyeh, a prominent moderate Ḥamās member, who, conversely, had been legitimately appointed Prime Minister of the Palestinian National Authority on February 16th, 2006, and later removed from his office, by disregarding the popular vote democratically acquired, not rebutted either by the defeated contenders, and with no international objections.

Fayyāḍ’s resignation could be regarded as a sign of President ‘Abbās’ political détente and openness, there is no doubt. And the provisional nature the observers ascribe to the new Ḥamdallāh’s administration could be interpreted in the same direction. But we hope that this will be a prelude to a successful reflection not only on the political balance of powers involved in the management of the State apparatus, but also on the wide range of ideal conceptions inspiring the political components, without excluding the bearers of religious instances forming an integral part of the Palestinian identity. In other words, institutional patterns of the new State of Palestine that are borrowed from Western secularist ideologies lead, as in the recent past it has already happened, to an attempt to discredit democratic processes which, instead, must be defended in their structure. The rejection of the political and social leadership of movements inspired to religious views and right appointed by the popular will, contradicts on the root the legal basis of democracy.

It is true that the very notion of democracy is embedded in the Islamic thought, albeit with motivations and developments far away from the secular European Enlightenment and its subsequent outgrowth. However, you cannot ignore all the debates surrounding the concepts of Shura and Shuracratīyya: some their interpretations are not very different from the contents of Western democracy in terms of right to life, equality under the law, social justice, freedom of thought and conscience.

The same logic should apply to the management of international relations, when the spirit of the time would refuse religious phenomena as determining factors of ignitions and social consolidation, because deterred by the difficulty of quantitatively measuring the weight and effects of collective ethical behavior; of course, actions based on material interests (e.g. takeover of energy resources, claiming of geo-political areas or the demand for economic and financial performances) are more predictable. In this respect, international disciplines show a serious delay, while witnessing a politico-religious awakening on a popular level, which is broadly misunderstood and underestimated by the so called “experts” of this sector.

In view of these considerations, a Palestinian perestrojka would be desirable for unity in diversity, to an autonomous political accountability, never subject to interests often corruptive and deviating from the historical task assumed by Palestine.