Civil society and Muslim NGOs have acted as aggregators of ethical and spiritual values generating a system of support for social services and social justice

By Glauco D’Agostino

Abstract:

The topic here is the contribution the Muslim NGOs have granted to the humanitarian, emergency and development sectors through instruments of wealth redistribution such as zakāt and ṣadaqa, both justified by motivations of a purely spiritual and religious nature, whose cornerstone is the Qur’an. The concept of a shared and sustainable development linked to social justice has been welcome in the Islamic world in the wake of the 1992 Rio Declaration. The problem is to run from short-term relief local projects to long-term solutions. The original prototypes of poverty alleviation and development aid are the Bangladesh and Malaysia experiences of microcredit, microfinance and economic development.

Zakāt organisations base in many countries of the “Western” world, where some not explicitly Islamic charities run projects for poverty alleviation using zakāt funds without ever diversifying aid on a religious basis. In some African countries, a new ideal of Islamic democracy in the 1980s has resulted in the establishment of free associations devoted to humanitarianism and development, and in Asia, above all in Indonesia, the zakāt organisations are taking shape as the emerging Third Sector. An interesting phenomenon is the worldwide civil society networks active on the Palestinian issue. The Muslim NGOs can compete (where permitted) on the floor of efficiency, effectiveness, accountability and transparency with public agencies collecting zakāt funds. However, civil society and NGOs have acted as aggregators of ethical and spiritual values generating a system of support for social services and social justice.

Keywords:

Civil society, globalisation, Third Sector, Muslim NGOs, zakāt, emergency, sustainable development, social justice, microcredit, microfinance, Islamic democracy.

***

Introduction

The growing role of civil society in international crises has long been a consolidated element in the era of globalisation for its ability to intervene in humanitarian emergencies and development, in the urgencies following natural disasters and even in promoting the economic and social development of peoples and local communities. This resulted in a new awareness of the possibility of overcoming boundaries and competencies of national states, the opportunity for collaboration (still essential) with the state organisation structures, the need to refer to shared ethical and moral guidelines and the demand for structures designed to develop and provide knowledge and expertise to industry insiders and the involved populations.

However, if this process seems widely appreciated by many (regardless of ideological, political and religious) as an example of positive subsidiarity and “horizontality” role of society with respect to the public institutions (Chalcraft, 2012), many scholars warn about dangerousness of a mechanism defined as “political” that would impose stabilisation of the “status quo” and reabsorption of ongoing international and political conflicts. Benoît Challand (2005), Associate Professor of Sociology at The New School for Social Research, New York, says:

The overuse of ‘civil society’ by certain actors (mostly from NGOs of the secular left factions) was hiding a phenomenon of ‘professionalization of politics,’ whereby NGOs gradually shifted from popular self-organization into a form of elite work funded by foreign donors. Put differently, many of these popular grass-roots committees that were so essential to political factionalism turned into professional client-oriented and elitist development institutions.

The very definition of “civil society” that Mary Kaldor gives in Old Wars, Cold Wars, New Wars, and the War on Terror (2005), though from a different perspective, gives rise to this type of reading, when confirming that it is a “process through which groups, movements and individuals can demand a global rule of law, global justice and global empowerment.” Hence the interpretation that the intervention of civil society as an emergency and development actor would be politically oriented (expression of neo-liberal globalisation) and influenced by wealthy donors of the dominant international organisations, which are often sponsors of small national voluntary associations (Chandler, 2010).

In this context, the civil society of the Muslim-majority countries has reached a considerable level of activities in the humanitarian and development sectors and has played the aggregating function of ethical and spiritual values that have resulted in a system of support for social services and social justice. In this sense, the Islamic religious organisations have made the greatest contribution both in normal conditions (such as the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt) and in war emergency (such as Ḥizb Allāh in Lebanon and Ḥamās in Gaza), using the solidarity network the Islamic Umma as a whole is deemed available to provide. Here the problem is to distinguish, in the context of “civil society” meanings, organisations emanating directly from political-religious subjects, Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) and the third sector, as recognised in the public debate also of the Muslim countries. However, whatever their classification, there is no doubt that the discussion (often more of an academic nature or biased politics) has emerged due to the growing activism of Islamic NGOs on the international scene and for their prevalent orientation not to distinguish between Muslims and non-Muslims receptors.

Brian O’Connell (1999), former head of the Independent Sector,[1] had identified five constituent parts of civil society to include the government and business sectors: 1) the individual, 2) the community, 3) government, 4) business, and 5) the voluntary, nonprofit, independent sector. Similarly, Elizabeth Dunn and Chris Hann (1996) argue that “civil society should not be studied as a separate ‘private’ realm clearly separated in opposition to the state.”

This approach is overturned by Keane and Lohmann a few years later. John Keane (2003), of the University of Westminster, defines “civil society” as composed of:

non-governmental institutions [that] deliberately organize themselves and conduct their cross-border social activities, business and politics outside the boundaries of governmental structures, with minimum violence and maximum respect for the principles of civilised power-sharing among different ways of life.

Roger Lohmann (2007), a professor at West Virginia University, referring to the third sector, defines it as follows:

a cluster of tax-exempt and tax-deductible organizations that together constitute civil society and contrasted with ‘market’ and ‘state’ organizations.

Lohmann thus makes civil society and third sector coincide but leaves the above-mentioned problem about political and religious organisations open. Even Benjamin Gidron, a former professor at the Ben Gurion University of the Negev in Israel, says along with his co-writers (2003):

the third sector is comprised of organizations that are: 1) formal organizations, 2) nonprofit distributing, 3) private, 4) are independent (have mechanisms for self-rule), and 5) are voluntary (have philanthropic inputs, i.e., giving and volunteering, voluntary membership).

For his part, Costanzo Ranci Ortigosa (2001), a professor of Economic Sociology at the Polytechnic of Milan, Italy, defines the third sector as the set of independent institutions that share two things: “every one of them is organized non for profit; and each aims to serve the public interest.”

With this background and considering what Payton says about philanthropy (“religion is the most influential private stimulus in international philanthropy”, Muhtada, 2014), we are dealing with the contribution the Islamic organisations of the third sector (therefore not in the public sphere and independent from political-religious subjects) have given to the humanitarian, emergency and development sectors[2] to improve economic conditions and social justice through means of wealth redistribution as zakāt (legal alms) and ṣadaqa (voluntary charity in addition to zakāt). Considering that in some Sunni Muslim countries (Libya, Malaysia, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, and Yemen) zakāt is part of the public tax system and in five countries (Indonesia, Brunei, Sudan, Yemen, and Saudi Arabia) government agencies are in charge of its gathering (Ismail, 2018), we will disregard the analysis of these agencies.

The debate on the behaviour of Muslim NGOs or Islamic Social Institutions is influenced by various scholars’ stances that we can summarise in the following assumptions:

- Muslim NGOs are the response to the personal interest that permeates action in modern society and which hampers the pursuit of common community goals (Dunn and Hann, 1996);

- Muslim NGOs hide a political agenda;

- Muslim NGOs (as in general other charitable organisations) have a political dimension that is part of the politics of global humanitarianism and are therefore influenced by the states they belong to (Benthall and Bellion-Jourdan, 2003);

- Muslim NGOs, as voluntary independent organisations or even in contrast to the state, are evidence of the “efforts for the revitalization of Islam through institutional modernization towards participatory politics” (Mitsuo, 2001) and “agents of transformation” (Browers, 2006).

As we can see, from this point of view, the debate focuses on the meaning of the term “political” and the conceptions that underlie the thought of those who interpret it. But it is also true that this dispute over the political dimension of Islam and its social implications in the commitment of volunteering seems to be out-of-date, powered only by those who failed to evaluate the past strong political pressure of the “international community” through a “colonising” tendency while using national and international emergency and development public policies. The notation moves ethical considerations on the assumptions of humanitarian action, too often a vehicle of economic and geo-political interests. In this regard the Islamic principles and doctrine indicate some fundamental pillars not always present in Western thought and practices:

- The economy is the servant of values;

- Social solidarity is one of the hallmarks whereby a mere plurality of individuals becomes a community;[3]

- Social justice is expressed not only by satisfying the essential material needs, but also the ethical, civic and cultural.[4]

In 1993 the Organisation of the Islamic Conference adopted a resolution on Human Rights, which reiterated “the interdependence and indivisibility of economic, social, cultural, civil and political rights” and recalled that “the international community has a duty to fulfill its commitment to eradicate poverty.” The resolution followed the Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam (OIC, 1990), the Draft Charter on Human and People’s Rights in the Arab World (Traer, n.d.) endorsed by the Arab Union of Lawyers in 1987, the Universal Islamic declaration of human rights (ICE, 1981) adopted by the Islamic Council of Europe[5] in Paris and London (Halliday, 1995), and the release in 1976 of the basic book Human Rights in Islam by Shaykh Syed Abū ‘l-Aʿlā Mawdūdī (2007), a champion of the contrast to the westerly ideologies (liberalism, capitalism, socialism).

The 1993 Resolution, in the wake of the U.N. Conference on Environment and Development held in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, introduced also the concepts of participatory[6] and sustainable development, interrelated with “democracy, universal enjoyment of all human rights, and social justice.” The following year, Moḥamed I. Anṣārī, a professor of Economics at the Athabasca University, Northern Alberta, Canada, highlighted “the spiritual aspect of sustainable development … and social justice” as they are articulated in Muslim thought, and “the obligation on the part of human beings to safeguard the resources of the natural world for future generations” (Saggiomo, 2012).

The doctrinal premises and the methods of zakāt management

The doctrinal premises and the methods of zakāt management

If these reasons, endorsed by scholars and international Islamic organisations, can be universally shared on a sociological level, other motivations of a more strict spiritual and religious nature are the ones actually justifying the wide use of zakāt as a tool for financing social actions promoted by Muslim NGOs. Zakāt, one of the Pillars of Islam, expresses the ideal of solidarity inspiring Islam since its inception and is consecrated to the principle of mutual assistance.[7] The late German legal anthropologist Franz von Benda-Beckmann (2007) says:

Zakat literally means ‘that which purifies’. It is a form of sacrifice which purifies worldly goods from their worldly and sometimes impure means of acquisition, and which, according to God’s wish, must be channeled towards the community … No worldly return is expected, it is in this aspect of non-reciprocity in secular terms that the great potential of zakat for social security purposes resides.

The cornerstones are in the Qur’an;[8] for instance:

Then shall anyone who has done an atom’s weight of good, see it! (XCIX:7);

and:

Whoever works righteousness, man or woman, and has Faith, verily, to him will We give a new Life, a life that is good and pure and We will bestow on such their reward according to the best of their actions (XVI:97).

The latest quoted āya (verse) recalls the concept of thawāb, that is, the spiritual reward both in this life and afterlife from good deeds and piety. Furthermore, the Qur’an explicitly opts for a fair distribution of wealth in society, when it states:

What God has bestowed on His Apostle (and taken away) from the people of the townships,- belongs to God,- to His Apostle and to kindred and orphans, the needy and the wayfarer; in order that it may not (merely) make a circuit between the wealthy among you (LIX:7).

As an obligatory (farḍ) and civic duty for Muslims whereby expression of social solidarity, zakāt does not qualify as a gift for the less fortunate, but it is a right (Ḥaqq) (May, n.d.).

Apart from those countries where the State levies zakāt directly, there is ample room for the third sector as a mediator between donors and earners, always taking into account that it is not required to call on a zakāt organisation. However, Dani Muhtada (2014), of the Department of Political Science, Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, USA, believes there are at least four reasons for choosing this option:

First, zakat can be managed more professionally. Zakat institutions can make such efforts as social and economic mapping, surveys, and systematic empowerment planning so that zakat funds can be managed and distributed more efficiently and effectively. Second, the existence of a zakat institution enables a zakat payer to pay the zakat more easily … Third, the poor and the needy know where to go when they need zakat funds. Fourth, the management of zakat by a zakat organization requires accountability and transparency, which need for things like annual reports, an independent audit, and feedback from the public.

Ester Sigillò (2016), currently working at Scuola Normale Superiore of Pisa, Italy, reports that in Tunisia the religious associations have created “shared databases in order so as to avoid duplicative interventions,” established “organic links with their constituencies more quickly and more efficiently than other associations” and “in mobilizing volunteers, they usually do not rely on formal hiring procedures but rather on informal ties of loyalty and trust.”

M. Ashraf Al Haq and Mohammad Omar Farooq (2017), the former from the Islamic Business School of the University Utara Malaysia, the latter from the Department of Economics and Finance of the University of Bahrain, underline:

Many Muslims have little trust in their government and therefore instead of giving zakat to the government would prefer to retain their right to privately give zakat.

Bilal Ahmad Malik (2016), from the Centre of Central Asian Studies, University of Kashmir, Śrīnagar (Jammu and Kashmir, India), makes severe judgments, yet, regarding the effectiveness of the government-run zakāt system in Pakistan:

The government’s own reports suggest that the state-administered system has had little impact on the reduction of inequality.

The finger is pointed not only at the government management of zakāt where it is compulsory, but also at the lack of wisdom of some governments to focus on this means as an investment opportunity for fighting against poverty and for development. Isahaque Ali and Zulkarnain Hatta (2014), the former from the Department of Sociology and Social Work of the Gono University, Dhaka, Bangladesh, the latter from the Department of Social Work of the School of Social Sciences, University Sains Malaysia, say:

Although the government of Bangladesh is very keen to alleviate poverty, it has never seriously looked at the institution of zakat as a national strategy for poverty reduction. For the fiscal year 2012–2013, the government of Bangladesh did not include zakat as one of the poverty reduction programs.

According to the non-profit media venture IRIN (Integrated Regional Information Networks, 1 June 2012),

every year, somewhere between US$200 billion and $1 trillion are spent in ‘mandatory’ alms and voluntary charity across the Muslim world.

Chloe Stirk (2015) states that in 2013 the international humanitarian assistance from governments within the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) was worth over US$2.2 billion, and according to Salman Ahmed Shaikh (2016), from the National University of Malaysia,

the aggregate resources pooled together from the potential Zakat collection in 17 [selected] OIC countries will be enough to fund resources for poverty alleviation in all 17 OIC countries combined.

This, despite the financial restrictions imposed by various anti-terrorism regulations have undoubtedly influenced the Muslim NGOs ability to raise funds by potential foreign donors, penalising especially those conflict zones where the population resorts to a trust-based informal value transfer system, such as the ḥawāla (Barzegar, El Karhili, 2017; Charity Finance Group, 2015): for example, the impact of these financial measures has had devastating results on aid to Yemen (El Taraboulsi-McCarthy & Cimatti, 2018); and in 2014 many British NGOs have relinquished their Middle East programs, some of which because of a shut-down of their bank accounts (Dyke, 2014). Rafia Khader (2018), from the Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, Indiana University, Indianapolis, says:

For Muslims, where interest is considered forbidden and anonymous giving is encouraged, it is not difficult to see why or how these informal [ḥawāla] networks have become so popular.

Consequently, the problem lays on the use of financial resources not only for humanitarian emergencies but still for international development projects, which by their nature imply cooperation and aggregation of different funding sources (Habib, 2004). For this purpose, the means of ṣadaqa (voluntary alms that can be devolved for all the causes deemed as worthy and does not distinguish between Muslim and non-Muslim donors) seems less exposed to the meticulous examination by the banking institutions and therefore more suited to the promotion of international development projects.

The distinction between emergency and development seems a cornerstone of the discussion about the use of zakāt. Some scholars (Khan, Tahmazov and Abuarqub, 2009) emphasise this difference:

Providing relief is extremely important but it is generally only a short-term solution to a long-term problem. Self-sufficiency through economic and social change, by contrast, is a long-term solution.

Sydney, Lakemba Mosque

There is a hermeneutic debate about the categories of zakāt recipients mentioned in the Qur’an,[9] and this implies that some interpretations argue you cannot use zakāt for “physical facilities and infrastructure that provides an ongoing service to the members of these groups” (Bremer, 2013). For instance, the United Muslims of Australia (UMA), “which invests in development and leadership programs that serve the Australian community”,[10] stated clearly that “Zakat cannot be given for the construction of Masjid, Madrasah, Hospital, a well, a bridge or any other public amenity.” On the other hand, in Egypt zakāt funding is used for building school, in Egypt, Lebanon, and Malaysia for building housing, and generally in rural villages for building mosques, bridges, hospitals, factories, homes for orphans and the elderly, and other facilities (Bremer, 2013). This uncertainty about the use of zakāt led to a donation preference to small Muslim NGOs working in short-term relief local projects, rather than large zakāt organisations involved in development projects, thus penalising the long-term solutions (Metcalfe-Hough, Keatinge and Pantuliano, 2015).

The zakāt organisations in the “Western” world

There are zakāt organisations in many countries of the “Western” world. The National Zakat Foundation (NZF) Worldwide, currently working in Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom, is an umbrella organisation seeking to build zakāt institutions in countries lacking state official zakāt infrastructure (UNRWA, 2017). From Australia operates the zakāt organisation Human Appeal, which promotes many international initiatives in favour of water wells, shelter, food and medical aids, emergency, orphans and education programs, and so on.[11] The Zakat Foundation of America (ZF), operating in 30 countries with a total public support and revenues of over US$ 8,5 million in 2015 (Knutte & Associates, P.C., 2016), is a Chicago-based non-profit international charity organisation with many programs providing emergency relief, as well as sustainable development, education, health and nutrition, orphans and child welfare, water and sanitation, and disaster preparedness.[12]

In Europe, a big boost to the Muslim NGOs has come since the emergency following the disintegration of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1991 and the declaration of independence of Bosnia and Herzegovina the year after. Precisely in these situations and with the ideal motivation to bring relief to the suffering people of that land, some of the most interesting international initiatives in this field were born. The UK-based Muslim Hands – United for the Needy, born in 1993, is now dedicated “to tackling the root causes of poverty around the world … working beyond the provision of immediate relief, towards supporting communities over the long-term.”[13]

The year before, a group of young people from Turkey had founded in Germany The Foundation for Human Rights and Freedoms and Humanitarian Relief (İHH), an NGO operating primarily in war-zones or war-torn countries, regions struck by natural disasters and poverty-stricken territories. Officially registered in Istanbul in 1995, İHH today operates in 135 countries and territories.[14] Its birth is part of the revival climate of Islamic identity in Turkey as opposed to the Kemalist secular authoritarianism, which enables the emergence from the bottom of civil society in a reformist effort giving ample space to the demand for social justice and the relative role of the third sector (Salim, 2012). After the brief interlude of Necmettin Erbakan’s Islamist government and Ahmet Mesut Yılmaz’s nationalist’s following the 1997 anti-Islamist coup, a revitalised civic society movement is back on the public stage, encouraged by the 2002 victory of the Justice and Development Party under Erdoğan’s leadership (D’Agostino, 2014). Before its 2011 break with the government, this revival advantaged also hizmet hareketi, the transnational Islamic social movement of the Turkish preacher Fethullah Gülen, who lives in Pennsylvania and is working on a humanitarian level in many countries through the Istanbul-based Kimse Yok Mu Association (KYM).

As for the UK, 56 British Muslim charities are engaged in international development and/or humanitarian aid. Just in England and Wales, the non-ministerial government department Charity Commission responsible for those territories said that over 1,600 Muslim charities registered (Metcalfe-Hough et al., 2015). Among the NGOs working internationally, Islamic Relief Worldwide (IRW)[15] stands out, supporting “Muslims and non-Muslims without a significant conflict of interest because Zakat is only one source of their funding” (Ismail, 2018). The organisation launched in 2014 the Humanitarian Forum initiative, “a network of key humanitarian and development organizations from each of Muslim donor and recipient countries, the West and the multilateral system,” which empowers “civil society groups at all levels.”[16] Other charities, not openly Islamic, run projects for poverty alleviation without religious discrimination of the recipients; and some of these projects use funds from zakāt, which shows that donations from Muslim faithful are not only justified by the desire to help other Muslims, but vice versa they don’t diversify aid on a religious basis. This type of charities inspired Penny Appeal, “set up in 2009 to provide poverty relief across Asia, the Middle East and Africa by offering water solutions, organising mass feedings, supporting orphan care and providing emergency food and medical aid.”[17] On its homepage, you can read out “100% zakat policy,” a need required by its majority donor base.

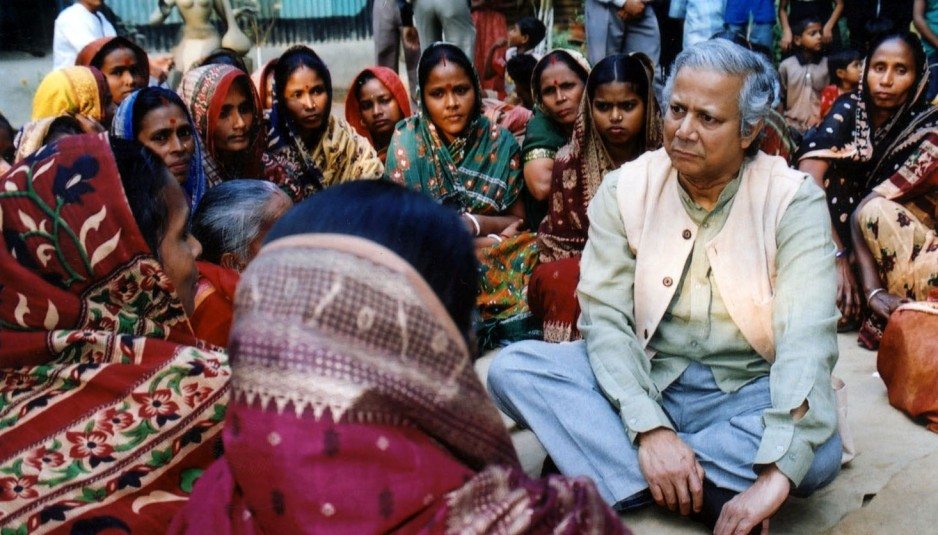

Microcredit and microfinance in Bangladesh and the emerging Third Sector in Indonesia

Given the level of extreme poverty affecting a large part of the Muslim world (Mohamed-Saleem, 2014),[18] an original example of poverty alleviation and development aid in this context is still the outstanding microcredit and microfinance experience developed in Bangladesh (where almost half the population is below the poverty index, Ali and Hatta, 2014) at the University of Chittagong by social entrepreneur Muḥammad Iunus [pictured above], winner of the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006. The successful test of small loans with no guarantees granted in 1976 to rural households with the burdens of high interest rates under predatory lending and the subsequent authorisation in 1983 of the Grameen Bank as an independent bank for the rural poor people can be considered the prototypes of both humanitarian and development interventions inspiring future Muslim NGOs, although not all using the typical instruments of an institution still operating in the banking sector (Green, 2015).[19] Even so, ever in the microcredit sector, Iunus’ experience was emulated since its debut in 1987 by the Amanah Ikhtiar Malaysia (AIM), a Malaysian Islamic NGO providing microfinance, savings, security and economic development services, which claimed in 2010 to have the world’s highest repayment rate (99.2%) (Fox, 2010).

Also in Indonesia, the zakāt organisations are taking shape as the emerging Third Sector, providing services in the health, economy, education, agriculture, and disaster relief areas, even though here there are limits of accountability, transparency and lack of economic development programs (Muhtada, 2014). Three of these organisations represent the prototype that inspired even the small Muslim NGOs: Dompet Dhuafa Republika (DDR), founded in 1993 by a community of journalists of the Jakarta-based newspaper Republika; Rumah Zakat (RZ), born in 1998 in Kota Bandung, on the island of Java, from a preacher study group called Majlis Ta’lim Ummul Quro; and Pos Keadilan Peduli Ummat (PKPU Human Initiative), established in 1999 by a group of young people to alleviate the difficulties of the poor people caused by the 1997-99 Asian monetary crisis, and registered in 2010.[20]

Historically, the breakthrough came in 1998, the fall of Gen. Soeharto, 2nd President of Indonesia for 30 years, but the year before, yet, 11 institutions (including DDR) had created the Forum Zakat (FOZ) with the mission of “directing zakat management organisations so as to achieve optimisation of mobilisation and synergy of zakat.”[21] In this task, the NGOs coexist with the Badan Amil Zakat Nasional (BAZNAS), which is rather a Non-Structural Institution that is financed by the state budget (but can involve the government, the private sector and civil society), and with the Badan Amil Zakat Infaq Sedekah (BAZIS), zakāt agencies established by some local governments.

Focus group discussion on Islamic philanthropy conducted by Ministry of Religion Affairs of Republic Indonesia, Jakarta, April 8th, 2019

Among the best and early initiatives of the Indonesian Muslim NGOs, there is the Free Health Services (LKC) system, a non-profit DD-networked institution serving poor verified members, which are then surveyed by a dedicated team.[22] But the RZ’s programs in the areas of health, education, economics, and environment are also valuable, since in 2018 they benefited nearly 3 million people, according to the organisation itself.[23] RZ also manages the program Empowered Village (Integrated Community Development) through an integrated approach. 73.14% of Indonesian villages and sub-districts “have agricultural typology to support national food self-sufficiency. Collaboration is needed to alleviate poverty in the village which reached 16.31 million or 13.47%, still higher compared to urban poverty,” as stated in its Company Profile.[24]

The effects of the Earthquake Tsunami in Indonesia (2018)

The zakāt organisations in Africa

In Africa, the origin of Muslim NGOs is due to the Arab countries engagement to meet the humanitarian and development emergencies of local economies caused by the 1973 and 1979 oil crises, to the needs following the economic crises aroused by their independence seasons, and, even more, as a result of the failed financial policies implemented through the Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs) of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, as Valeria Saggiomo, professor of International Development Cooperation at the University of Naples L’Orientale, points out in her already mentioned essay. A further important factor was the return in the ‘80s of the African diaspora young people to their native countries, with the introduction of new ideals of Islamic democracy and civil society mobilisation that engendered the establishment of free associations dedicated to humanitarianism and development.

After the Arab Springs erupted and new social actors of civil society (in the past hampered by authoritarian institutions) emerged, the phenomenon of independent Islamic associationism strongly appeared especially in Tunisia, where its action has developed primarily in the poor urban areas using zakāt and ṣadaqa (Sigillò, 2016). The local Muslim NGOs action was supported, yet, by NGOs based in other Muslim countries, primarily in the Gulf. The work of Qatar Charity, for example, was effectively driven in favour of post-revolutionary needs in the central and southern rural areas of Tunisia and, even more so, against the humanitarian emergencies of the Libyan refugees on the Tunisian borders after the Qaddāfī’s fall.[25] But also some Kuwait-based NGOs, such as the Shaykh ‘Abdullāh an-Nūri Charitable Society and the International Islamic Charity Organization, have made a large contribution standing out, moreover, for their transparency underlined by Forbes business magazine (Soli and Merone, 2013).

After the Arab Springs erupted and new social actors of civil society (in the past hampered by authoritarian institutions) emerged, the phenomenon of independent Islamic associationism strongly appeared especially in Tunisia, where its action has developed primarily in the poor urban areas using zakāt and ṣadaqa (Sigillò, 2016). The local Muslim NGOs action was supported, yet, by NGOs based in other Muslim countries, primarily in the Gulf. The work of Qatar Charity, for example, was effectively driven in favour of post-revolutionary needs in the central and southern rural areas of Tunisia and, even more so, against the humanitarian emergencies of the Libyan refugees on the Tunisian borders after the Qaddāfī’s fall.[25] But also some Kuwait-based NGOs, such as the Shaykh ‘Abdullāh an-Nūri Charitable Society and the International Islamic Charity Organization, have made a large contribution standing out, moreover, for their transparency underlined by Forbes business magazine (Soli and Merone, 2013).

In some countries of ancient tradition, the Muslim NGOs have had to mediate the humanitarian aid deriving from zakāt with the traditional assistance typical of the pre-Islamic tribal solidarity.[26] In other countries, disrupted by the fall of strongly centralised regimes (as in the Somali case of Moḥamed Siad Barre in 1991), the Muslim NGOs, concurrently with the extension of Sharī’a as the basis of the judicial system combined with customary legal systems in many regions, have played a key role, especially in the areas of food and health emergency and education. In the latter case, replacing the function of the Ministry of Education of Somalia, the role of private education has been increasing; in particular, it is worth noting the work of the Formal Private Education Network in Somalia (FPENS), which since its founding in 1998 has been national leader in providing quality education with the purpose to eradicate illiteracy from the country.[27]

The role of Muslim NGOs in Palestine and Gaza

An interesting and emerging phenomenon is the worldwide civil society networks active on the question of Palestine and composed by more than 1,000 “national and international non-governmental organizations (NGOs), organizations involved in political and humanitarian work, NGOs promoting human rights or economic and social development, solidarity-, charity- or action-oriented groups, churches, academic institutions, trade unions and professional associations, and organizations that focus on women, children, refugees and detainees” (United Nations). The reference bodies are the Committee on the Exercise of the Inalienable Rights of the Palestinian People, which has a mandate from the U.N. General Assembly, and its Working Group. On the issue of “shrinking space for civil society in developing countries,” even the European Parliament (2017) reiterated in a resolution “its unequivocal call for continued and increased EU support and funding in creating a free and enabling environment for civil society at country and local level.”

The situation in Gaza has been particularly serious since donors from Western countries have dropped dramatically due to political reasons, i.e. the Strip control by Ḥamās. In fact, in 2006, the Islamic Resistance Movement had won elections throughout Palestine, reaching an absolute majority (76 seats out of 132) in the Palestinian Legislative Council, and Ismā’īl Haniyeh, a former headmaster of the Islamic University of Gaza, was legitimately appointed Prime Minister of the Palestinian National Authority. But, despite the polls have not been disproved either by the defeated parties and had not received international disputes, incredibly, the Western countries had opposed harsher sanctions to the Palestinian democracy (D’Agostino, 2010). In 2008, the World Bank denounced an “alarming deterioration in the ability of civil society organizations in both the West Bank and Gaza to continue cater to vulnerable groups … Many of the closed NGOs in Gaza were funded by UN agencies and other donors, including the World Bank … Children and youth were affected as were job creation programs serving some of the poorest households.” In addition, the Israeli Operation Cast Lead against Gaza in 2008-2009 and the ensuing siege led to a humanitarian crisis for the entire Strip population.

The desperate appeals of NGOs from around the world and the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East mobilised Muslim and non-Muslim civil society (Salim, 2012). The aforementioned Turkish NGO İHH was among the first to intervene and both unwilling protagonist and victim of a serious mishap. In 2010 it organised with other associations the Gaza Freedom Flotilla, comprising three passenger ships and three cargos carrying 10,000 tons of aid for Gaza. Numerous global civil organisations and some European and international parliament members participated in this initiative. Israeli naval commandos from helicopters came aboard the ship Mavi Marmara, a Turkish passenger vessel that was carrying about 600 activists, killing nine of them (Kershner, 2010). The ominous episode caused a wave of solidarity from the international civil society especially from Europe and the Islamic world, as well as repercussions on the diplomatic front. İHH itself began a series of humanitarian programs still in progress in various fields on a basis of people-to-people approach. (Salim, 2012):

- In the health area, it provides hospitals with emergency medical supplies in addition to treating injured Palestinians in Turkish hospitals;

- On a welfare level, it sponsors more than eleven thousand orphans, paying university fees to those who attend university, and it helps poor people especially who had his home destroyed during the Gaza War;

- In terms of religious solidarity, it carries special programs donating zakāt money during Islamic occasions such as Ramaḍān and ‘Īd al-’Aḍḥā, and cooperates with the municipalities in distributing food baskets and meat.

However, the Turkish NGO action in Gaza is not just limited to the humanitarian sector, but gives studies and economic resources to finance development programs aimed at empowering people ability and social awareness, often involving local administrations. For example, it built hospitals and trained surgeons to allow medical operations on the spot; it has allowed the reconstruction of university laboratories, especially in the area of Information Technology, and helped, in cooperation with a local NGO, the inclusion of young people into the working world through the Ottoman Centre; it has helped to carry out projects of water networking, wells for drinking water and solid waste equipment, it established cutting and embroidery centres for the fashion industry and set up projects for agriculture and aquaculture (Salim, 2012).

The Saint George Monastery in Deir Al-Balah, Palestine, before and after restoration by the local NGO NAWA for Culture and Arts (from Palestine Square, January 4, 2017)

Conclusion

It now seems generally accepted that zakāt organisations can fully enrol among the subjects outside the public system contributing most to the rebalancing of economic and social dynamics in favour of the needy and the weakest. It is because they meet by nature the zakāt ethic feeling, which takes the shape of a wealth transfer instrument for poor and marginalised people and pursues equity and solidarity goals. The same feeling inspiring the Islamic Social Finance and those theories fighting the imposition of not finalised bank interests as an expression of speculation: an alternative context in which the use of zakāt in today’s society is fully part. In practice, even the zakāt financial circuit is an independent banking system, albeit with different aims and methods from the traditional one, which could meet the needs of a third of the world’s population that does not use formal financial services.

These primary features, yet, require Muslim NGOs to structure for the management of complex programs, by detecting methodologies, aims, goals, analyses of results, assessments and monitoring, and by implementing administrative structures able to cope with zakāt gathering and distribution, bodies for managing the relations with public and private partners, and communication and information structures to involve the public opinion of related territories. Of course, this framework is an ideal destination (or the desired departure, if you will) that does not always match the reality of the organisations involved in this social project so important. It is positive that more and more Muslim NGOs relate to other international organisations engaged in the emergency and development fields, and with supranational institutions driving coordination processes of interventions on the spot. It leads to a greater awareness of the shared global goals and the importance of dialogue even beyond the narrow faith limits.

An example in this sense are the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) agreed at the UN in 2015 and which also openly inspire many Muslim NGOs in finalizing the zakāt funds, receiving consent and recognisability both from donors and earners, who are not always part of the Islamic Umma. Therefore, the new Agenda 2030 can also raise the Islamic World awareness of the new opportunities provided by the implementation of sustainability (which is the glue of the goals), helping to address the problems not only of economic inequality but also related to long-term environmental difficulties and the introduction of modern and forthcoming technology. For this purpose, precisely the final goal fosters developing multi-stakeholder partnerships, in particular, the public-private ones involving civil societies.

These issues are on the table in the Islamic world, which has huge potential just due to its habit with the zakāt solidarity principle shaping trends and resulting social behaviours. And the Muslim NGOs (this paper shows some examples in different continental realities) are already structured enough to affect the destinies of millions of people in need. They only require looking ahead to the critical dimension making a real difference with respect to times too plagued, yet, by material and spiritual problems.

Ultimately, it seems we can say that civil society in the Muslim-majority countries has become aware of its role in the humanitarian and development sectors; and that the Muslim NGOs should optimise their operations but can compete (where permitted) on the floor of efficiency, effectiveness, accountability and transparency with public agencies collecting zakāt funds. However, civil society and NGOs have acted as aggregators of ethical and spiritual values that have resulted in a system of support for social services and social justice.

***

[1] A coalition of nonprofits, foundations and corporate giving programs created in 1980 in Washington, D.C.

[2] On the concept of development in the Islamic world see Abdul Haseeb Ansari, Parveen Jamal, Umar A. Oseni (2012) and Mohammed Ralf Kroessing (2008).

[3] A reference is ḥadīth n. 19049 in the book As-Sunan al-Kubra by Imām Shafi’ī Abū Bakr al-Bayhaqi: “He is not a believer whose stomach is full while his neighbor is hungry” (May, n.d.).

[4] This concept is correctly expressed by Syed Othman Alhabshi: “The material life has to be governed by Islamic injunctions as much as the spiritual. The integration is based on the ‘Unity’ or ‘Tawhidic’ paradigm which needs to be translated into actions, whether in the realm of the material or spiritual.” (Alhabshi, n.d.).

[5] The Islamic Council of Europe (ICE), headquartered near the East London Mosque, is an organisation founded in 1973 to coordinate the work of Islamic centres and organisations in Europe.

[6] “A comprehensive economic, social, cultural and political process, which aims at the constant improvement of the well-being of the entire population and of all individuals on the basis of their active, free and meaningful participation”, as stated in the OIC Resolution.

[7] Zakāt is to pay a proportional tax on annual net profits and applies to gold, silver, merchandise (with the rate of 2.5%); and products of the land and livestock (10% rate); but it can also include voluntary work and alms (D’Agostino, 2010).

[8] The references to the Qur’an relate the following issue: The Holy Qur’an. Translation and commentary by Abdullah Yusuf Ali, Islamic Propagation Centre International, Durban, South Africa.

[9] “Alms are for the poor and the needy, and those employed to administer (the funds); for those whose hearts have been (recently) reconciled (to Truth); for those in bondage and in debt; in the cause of God; and for the wayfarer: (thus is it) ordained by God, and God is full of knowledge and wisdom” (Qur’an, IX:60).

[10] So they define themselves on their website https://www.uma.org.au/.

[11] Retrieved from https://www.humanappeal.org.au/what-we-do/

[12] See Zakat Foundation of America, https://www.zakat.org/en/

[13] Retrieved from https://muslimhands.org.uk/about-us

[14] Retrieved from https://www.ihh.org.tr/en/about-us

[15] Islamic Relief Worldwide is a member of the UN Economic and Social Council and is a signatory to the Code of Conduct for the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement and NGOs in Disaster Relief.

[16] Retrieved from https://humanitarianforum.org/

[17] Retrieved from https://pennyappeal.org/about-us

[18] According to Amjad Mohamed-Saleem, from the Institute of Arab and Islamic Studies of the University of Exeter, Cornwall, UK, “it is estimated that one-quarter of the Muslim world is living on less than $1.25 a day (calculated by IRIN based on 2011 Human Development Index)”. Extreme poverty is defined as living on less than $1.90 a day, calculated using the national poverty lines of some of the world’s poorest countries at 2011 Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) $.

[19] Duncan Green, a strategic adviser for Oxfam, GB, records “a call for an organization such as the Islamic Development Bank to set up some kind of Zakat International.”

[20] Retrieved from https://pkpu.org/tentang-kami/?lang=en

[21] Retrieved from https://forumzakat.org/tentang-foz/

[22] Retrieved from https://www.dompetdhuafa.org/kesehatan/rs_terpadu

[23] Retrieved from https://www.rumahzakat.org/en/tentang-kami/sejarah/

[24] Retrieved from https://drive.google.com/file/d/1EYoM70JN2uRmYwYQ4Q8UYaAWZi2FYacq/view, pp. 44 and 52.

[25] Retrieved from https://www.qcharity.org/en/qa/qatar-charity-offices/tunisia/636?ddlMainAccountFastdonationSadaqa=1408

[26] The Northern Ghana case is documented in the essay by Holger Weiss (2002).

[27] Retrieved from http://fpens.so/en/

REFERENCES

- A faith-based aid revolution in the Muslim world? (2012, 1 June). IRIN. Retrieved from http://www.irinnews.org/report/95564/analysis-faith-based-aid-revolution-muslim-world

- Ahmad Malik, Bilal (2016). Philanthropy in Practice: Role of Zakat in the Realization of Justice and Economic Growth. International Journal of Zakat (IJAZ), 1(1), 64-77. Menteng, Central Jakarta, Indonesia: Center of Strategic Studies BAZNAS.

- Ahmed Shaikh, Salman (2016). Zakat Collectible in OIC Countries for Poverty Alleviation: A Primer on Empirical Estimation. International Journal of Zakat (IJAZ), 1(1), 17-35.

- Al Haq, M. Ashraf & Farooq, Mohammad Omar (2017). Zakat, Persistence of Poverty and Structural-Incidental Segmented Approach: A Survey of Literature. Journal of Islamic Financial Studies, 3(1), 17-31. doi: 10.12785/JIFS/030102

- Alhabshi, Datuk Syed Othman (n.d.). The Role of Ethics in Economics and Business. Retrieved from a download in https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237479257_POVERTY_ERADICATION_FROM_ISLAMIC_PERSPECTIVES

- Ali, Isahaque and Hatta, Zulkarnain A. (2014). Zakat as a Poverty Reduction Mechanism Among the Muslim Community: Case Study of Bangladesh, Malaysia, and Indonesia. Asian Social Work and Policy Review, 8, 59-70. doi: 10.1111/aswp.12025

- Ansari, Abdul Haseeb, Jamal, Parveen, Oseni, Umar A. (2012). Sustainable Development: Islamic Dimension with Special Reference to Conservation of the Environment. Advances in Natural and Applied Sciences, 6(5), 607-619.

- Barzegar, Abbas and El Karhili, Nagham (2017). The Muslim Humanitarian Sector: A Review for Policy Makers and NGO Practitioners. Retrieved from https://www.britishcouncil.us/sites/default/files/final_report_-_the_muslim_humanitarian_sector.pdf;

- Benda-Beckmann (von), Franz, Benda-Beckmann (von), Keebet (2007). Social Security Between Past and Future: Ambonese Networks of Care and Support. Münster: LIT Verlag.

- Benthall, Jonathan and Bellion-Jourdan, Jérôme (2003). The Charitable Crescent: Politics of Aid in the Muslim World. London, New York: I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd.

- Bremer, Jennifer (2013). Zakat and Economic Justice: Emerging International Models and their Relevance for Egypt. Tunis, Tunisia: Third Annual Conference on Arab Philanthropy and Civic Engagement, June 4-6, 2013. Retrieved from http://dar.aucegypt.edu/bitstream/handle/10526/4297/Zakat%20and%20Economic%20Justice%2052-76.pdf?sequence=1

- Browers, Michaelle L. (2006). Democracy and Civil Society in Arab Political Thought: Transcultural Possibilities. New York: Syracuse University Press.

- Chalcraft, John (2012). Horizontalism in the Egyptian Revolutionary Process. Middle East Report, 262, 6-11.

- Challand, Benoît (2005). Looking Beyond The Pale: International Donors and Civil Society Promotion in Palestine. Palestine-Israel Journal, 12(1), 56-63.

- Chandler, David (2010). International Statebuilding: The Rise of Post Liberal Governance. 1st Edition. New York: Routledge.

- Charity Finance Group (CFG) (2015). Impact of banks’ de-risking on Not for Profit Organisations (Briefing paper). Retrieved from http://docplayer.net/78310187-Briefing-impact-of-banks-de-risking-on-not-for-profit-organisations-march-background.html

- D’Agostino, Glauco (2010). Sulle Vie dell’Islam. Percorsi storici orientati tra dottrina, movimentismo politico-religioso e architetture sacre (Historical and Architectural Itineraries across the Muslim Countries). Rome, Italy: Gangemi.

- D’Agostino, Glauco (2014). Erdoğan’s Turkey to A Post-Kemalist Era. Retrieved from https://www.islamicworld.it/wp/erdogans-turkey-to-post-kemalist-era/

- Dunn, Elizabeth, Hann Chris M. (1996). Civil Society: Challenging Western Models. European Association of Social Anthropologists. London and New York, N.Y.: Routledge.

- Dyke, Joe (2014). Analysis: NGOs and anti-terror laws – how to keep your bank manager happy. Retrieved from http://www.irinnews.org/analysis/2014/12/31

- El Taraboulsi-McCarthy, Sherine & Cimatti, Camilla (2018). Counter-terrorism, de-risking and the humanitarian response in Yemen: a call for action, Humanitarian Policy Group Working Paper. London, United Kingdom: Overseas Development Institute. Retrieved from https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/resource-documents/12047.pdf

- European Parliament (2017). European Parliament resolution of 3 October 2017 on addressing shrinking civil society space in developing countries. Retrieved from http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//TEXT+TA+P8-TA-2017-0365+0+DOC+XML+V0//EN&language=EN

- Fox, Matthew (2010). Malaysian Microfinance Institution (MFI), Amanah Ikhtiar Malaysia (AIM), Claims “World’s Highest” Microcredit Repayment Rate of 99.2 Percent. MicroCredit. Boston, MA, USA. Retrieved from http://www.microcapital.org/microcapital-brief-malaysian-microfinance-institution-mfi-amanah-ikhtiar-malaysia-aim-claims-worlds-highest-microcredit-repayment-rate-of-99-2-percent/

- Gidron, Benjamin, Katz, Hagai, Bar-Mor, Hadara, Katan, Joseph, Silber, Ilana, Telias, Motti (2003). Through a New Lens: The Third Sector and Israeli Society. Israel Studies, 8(1), 20-59.

- Green, Duncan (2015). 1/4 of the world’s people already subject to large annual wealth tax to tackle poverty. Has anyone told Piketty? Retrieved from https://oxfamblogs.org/fp2p/tag/zakat/

- Habib, Ahmed (2004). Role of Zakāh and Aqwāf in Poverty Alleviation, First Edition (Occasional Paper No. 8). Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: Islamic Development Bank Group, Islamic Research & Training Institute.

- Halliday, Fred (1995). Relativism and Universalism in Human Rights: the Case of the Islamic Middle East. Political Studies, 43(1), 152-167. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.1995.tb01741.x

- Islamic Council of Europe (ICE) (1981). Universal Islamic Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the Islamic Council of Europe on 19 September 1981/21 Dhul Qaidah 1401. University of Minnesota, Human Rights Library. Retrieved from http://hrlibrary.umn.edu/instree/islamic_declaration_HR.html

- Ismail, Zenobia (2018). Using Zakat for international development. K4D Helpdesk Report. Retrieved from https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/123456789/13647/Using_Zakat_for_International_Development.pdf

- Kaldor, Mary (2005). Old Wars, Cold Wars, New Wars, and the War on Terror, public lecture delivered on behalf of the Cold War Studies Centre, London School of Economics, 2 February 2005. International Politics, 42(4), 491-498.

- Keane, John (2003). Global Civil Society? New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Kershner, Isabel (2010, May 31). Deadly Israeli Raid Draws Condemnation. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/01/world/middleeast/01flotilla.html

- Khader, Rafia (2018). 2018 Symposium on Muslim Philanthropy and Civil Society. Journal of Muslim Philanthropy & Civil Society, II(II), 76-81. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

- Khan, Ajaz Ahmed, Tahmazov Ismayil and Abuarqub, Mamoun (2009). Translating faith into development. Birmingham, United Kingdom: Islamic Relief Worldwide. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.561.4906&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Knutte & Associates, P.C. (2016). The Zakat Foundation of America Report on the Audit of the Financial Statements for the Years Ended June 30, 2015 and 2014. Darien, Illinois. Retrieved from http://zakat-publications.s3.amazonaws.com/4250/zf-2015-auditors-report.pdf

- Kroessing, Mohammed Ralf (2008). Concepts of Development in Islam: A Review of Contemporary Literature and Practice. University of Birmingham, UK, International Development Department, Religions and Development Research Programme, Working Paper 20. Retrieved from: http://epapers.bham.ac.uk/1501/1/Kroessin_2008_Concepts.pdf

- Lohmann, Roger A. (2007). Charity, Philanthropy, Public Service, or Enterprise: What Are the Big Questions of Nonprofit Management Today?. Public Administration Review, 67(3), 437-444. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00727.x

- Maududi, Sayyid Abulalá (2007). Human rights in Islam. 2nd rev. ed. Markfield, Leicestershire, UK: Islamic Foundation.

- May, Samantha (n.d.). Muslim Charitable Giving, Civil Society and the potential for Social Cohesion: Zakat and Sadaqah (draft). Retrieved from https://ecpr.eu/Filestore/PaperProposal/a9cb4efb-21d1-4005-86dc-b6b89ee061e5.pdf

- Metcalfe-Hough, Victoria, Keatinge, Tom and Pantuliano, Sara (2015). UK humanitarian aid in the age of counter-terrorism: perceptions and reality, Humanitarian Policy Group Working Paper. London, United Kingdom: Overseas Development Institute. Retrieved from https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/9479.pdf

- Mitsuo, Nakamura (2001). Introduction. In Mitsuo, Nakamura, Siddique, Sharon and Bajunid, Omar Farouk, Islam & Civil Society in Southeast Asia (1-30). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS). Retrieved from https://ibnughony.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/islam-and-civil-society-in-southeast-asia-mitsuo-nakamura.pdf

- Mohamed-Saleem, Amjad (2014). Understanding the role of ‘Zakat’ in humanitarian response. Bristol, United Kingdom: Development Initiatives Ltd. Retrieved from http://devinit.org/post/understanding-role-zakat-humanitarian-response/ and http://data.devinit.org/methodology.

- Muhtada, Dani (2014). Islamic Philanthropy and the Third Sector: The Portrait of Zakat Organizations in Indonesia. Islamika Indonesiana, 1(1), 106-123.

- O’Connell, Brian (1999). Civil Society: The Underpinnings Of American Democracy. Tufts University. Hanover and London: University Press of New England.

- Organisation of the Islamic Conference (OIC) (1990). Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam. Retrieved from https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Cairo_Declaration_on_Human_Rights_in_Islam

- Organisation of the Islamic Conference (OIC) (1993). Resolution No. 41/21-P on Coordination among Member States in the Field of Human Rights. Karachi, Islamic Republic of Pakistan: Twenty-First Islamic Conference of Foreign Ministers, Session of Islamic Unity and Cooperation for Peace, Justice and Progress. Retrieved from https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Cairo_Declaration_on_Human_Rights_in_Islam

- Ranci, Costanzo (2001). Democracy at Work: Social Participation and the “Third Sector” in Italy. Daedalus, 130(3), Part II Politics and Society, 73-84.

- Saggiomo, Valeria (2012). Islamic NGOs in Africa and their notion of development. The case of Somalia. Storicamente 8, Dossier Religion and Capitalism in Africa. Bologna, Italy: Alma Mater Studiorum – Università di Bologna, Dipartimento di Discipline Storiche, Antropologiche e Geografiche.

- Salim, Iyas (2012). From Humanitarian to Development Assistance Agency: Case Study of a Transnational Muslim Civil Society Organization, IHH in Palestine, Research Note. Journal of Global Studies, 3, 137-162. Kyoto, Japan: Doshisha University, Graduate School of Global Studies.

- Sigillò, Ester (2016). Tunisia’s Evolving Islamic Charitable Sector and Its Model of Social Mobilization. In Informal Networks and Political Transitions in the MENA and Southeast Asia, Washington, D.C.: Middle East Institute. Retrieved from https://www.mei.edu/publications/tunisias-evolving-islamic-charitable-sector-and-its-model-social-mobilization

- Soli, Evie and Merone, Fabio (2013). Tunisia: the Islamic associative system as a social counter-power. Retrieved from https://www.opendemocracy.net/north-africa-west-asia/evie-soli-fabio-merone/tunisia-islamic-associative-system-as-social-counter-power

- Stirk, Chloe (2015). An Act of Faith: Humanitarian Financing of Zakat (Briefing paper). Retrieved from http://devinit.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/ONLINE-Zakat_report_V9a-1.pdf

- The World Bank (2008). Palestinian Economic Prospects: Aid, Access and Reform Economic Monitoring Report to the Ad Hoc Liaison Committee. Retrieved from http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTWESTBANKGAZA/Resources/AHLCSept15,08.pdf

- Traer, Robert (n.d.). Religious Communities in the Struggle for Human Rights. Retrieved from http://www.religion-online.org/article/religious-communities-in-the-struggle-for-human-rights/

- United Nations. Civil Society and the Question of Palestine. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/unispal/data-collection/civil-society/

- UNRWA (20 November 2017). National Zakat Foundation Worldwide Declares UNRWA Programmes for Vulnerable Palestine Refugees Zakat Eligible. Retrieved from https://www.unrwa.org/newsroom/press-releases/national-zakat-foundation-worldwide-declares-unrwa-programmes-vulnerable

- Weiss, Holger (2002). Reorganising Social Welfare among Muslims: Islamic Voluntarism and other Forms of Communal Support in the Northern Ghana. Journal of Religion in Africa, 32(1), 83-109. doi: 10.1163/15700660260048483