A Country between an Ambiguous Past and a Full-Opening Future

by Glauco D’Agostino

Some of the themes used in the electoral game for the renewal of the National Assembly of Pakistan reveal a condition of extreme fragility of the country and the importance implicit in its geo-political position, on edge, as a non-Arab Islamic entity, between the territorial system of south-central Asia and the political-religious push to the Middle East.

Some of the themes used in the electoral game for the renewal of the National Assembly of Pakistan reveal a condition of extreme fragility of the country and the importance implicit in its geo-political position, on edge, as a non-Arab Islamic entity, between the territorial system of south-central Asia and the political-religious push to the Middle East.

We cannot adhere to the pessimistic positions expressed by the former CIA official Bruce Riedel, director of the Brookings Intelligence Project (part of the Brookings’ New Center for 21st Century Security and Intelligence), which predicts the collapse of Pakistan by 2030; but we must recognize that the situation in the Asian country leads to a serious reflection about its future.

Pakistan comes from the strong growth of the 2000s, with an average 7% annual GDP growth, which has given it as one of the Next Eleven after the BRICS, but its semi-industrialized economy remains today behind many of those in South Asia and mainly depends on international donations and loans from the International Monetary Fund, which are no longer sustainable. Moreover, do not help the difficulties facing the implementation of the South Asian Free Trade Area (SAFTA), the agreement signed in 2004 in Islamabad as part of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation and involving nearly 2 billion people in Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. These difficulties are due to the fact that Islamabad has long resisted the transit of commercial traffic through its territory, especially between India and Afghanistan.

However, the problematic nature of Pakistan is mainly due to its complex politics, to which contribute both the parliamentary forces, as the fundamentalist movements in the area, as, above all, the Armed Forces strong influence. The latter exert the real power, according to many analysts. It certainly does not help to appease the former President Pervez Musharraf’s recent admission on the secret agreement with the United States about drone attacks, which, according to the reliable New American Foundation, murdered at least 1,990 people only in Pakistan, including hundreds of civilians.

So, here are the main issues on the table, at the dawn of a new legislature, following the one in which a civilian government completes its 5-year term for the first time:

- First of all, the relationship between the federal government and the forces of national defense;

- then, the attitude Pakistan should take towards India, its traditional enemy because of the Kashmir issue, that dates now since the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947;

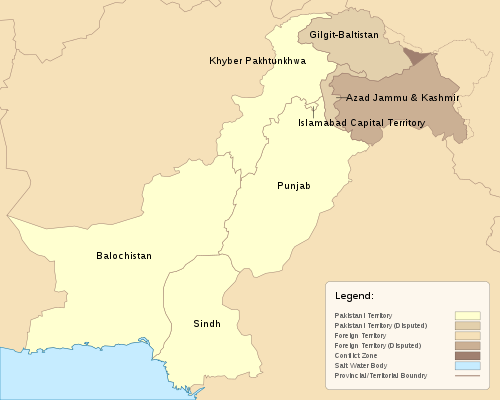

- the effective territory and borders control, especially in the Federal Tribal Areas, Waziristan and Swat Valley, not to mention the rising nationalism in Balochistan;

- the inter-ethnic and inter-religious sectarian violence and bloodshed in the country, with thousands of victims each year.

Regarding the first point, the Army and ISI, the intelligence service, are believed to be crucial on strategic matters (and therefore on the political attitude to be taken with neighboring India, Afghanistan and Iran), as well as for the management of relations with the Tālibān and the contrast of terrorist organizations. And the suspicions advanced in the United States have not yet been dispelled that the Armed Forces were not only aware of the location in which the Shaykh Osama bin Laden was living at the time of his murder (in Abbottābād, in the Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa province), but also they protected him.

Relations with India are definitely influenced by dated statements of General Ashfaq Parvez Kayani (Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces successor to Musharraf), who in 2008 in Brussels would have expressed the belief that Pakistan has nothing in common with India nor culturally or historically or linguistically. But new opportunities arise by the announcement that on April 23rd the main political parties in Pakistan (primarily the Pakistan People’s Party, the Pakistan Muslim League – Nawaz, the Pakistan Muslim League – Quaid, Pakistan Tehrik-e-Insaf) have pledged in their manifestos to promote peace with New Delhi. “The progressive detente with India will benefit both countries, it will be centered on conflict resolution and cooperation, in particular in the energy sector,” says the manifesto of Pakistan Tehrik-e-Insaf (Pakistan Movement for Justice) of Imran Khan.

Border control certainly concerns the issue of Jammu and Kashmir, which is divided by a border practically contested by both countries (India and Pakistan) and is the theater of operations of paramilitary movements such as the Deobandi Harakat ul-Jihād-i-Islami (Movement of Islamic jihād), Harkat-ul-Mujāhidīn-al-Islami (Movement of Islamic Fighters), Laškar-ĕ ṯayyiba (Army of the Good), Jaish-e-Moḥammed (Mohammed’s Army) and Ḥizb-ul Mujāhidīn (Freedom Fighters’ Party); but the question also relates to parts of the national territory not completely controlled by the State, virtually all those areas along the northwestern frontier with Afghanistan (the Durand Line), established 120 years ago, at the beginning of “Great Game”. Do not forget that:

– in these areas Mullāh ‘Omar took refuge after the fall of the Islamic Emirate;

– entire territories are today controlled by Baitullāh Mehsud, not surprisingly called the unofficial South Waziristan’s Emir, and his Deobandi movement Tehrik-i-Tālibān Pakistan (Movement of Pakistani Tālibān);

– the districts of Swat and Malakand have been legally governed under the Sharī’a law since 2009.

The issue of inter-religious conflicts particularly refers to the hostility of some Sunni components against Shia and Aḥmadi communities, the latter of which is so called after the name of its founder, Hadhrat Mirza Ghulām Aḥmad. The Shiites, about 20% of the Pakistani population, are accused of exercising too much power and influence, especially in the Punjab region, and that’s the main reason because they suffer attacks by Wahhabi anti-Shiite organization Laškar-e-Jhangvi. Ahmadiyya, on the other hand, has been declared not belonging to the Muslim community since 1974, when a constitutional amendment proposed by Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto was approved under pressure from the Deobandi movement: the measure had resulted in the escape from the country of Moḥammad Abdus Salām, an Ahmadi afterward Nobel Prize for Physics in 1979, and gave the pretext for persecution of the community that has not ceased, yet.

However, this situation of difficult and troubled coexistence was due to the flowering of political and religious conceptions, as well as historically established in Pakistan. I would like to remind that Muḥammad ‘Alī Jinnah, officially recognized in his homeland as Quaid-e-Azam (the Great Leader) and Baba-e-Qaum (Father of the Nation), was a Shia leader in a predominantly Sunni country; but also that:

– Karachi has been the birthplace of Sultan Maḥommed Shāh, Āgā Khān III and 48th Nizarite Imam;

– Jamā‘at-e-Islami (Islamic Block), the theo-democratic movement of Shaykh Syed Abū ‘l-Aʿlā Mawdūdī, was founded in Lahore;

– in Pakistan the Afghans commanders Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and Burhānuddīn Rabbānī respectively based Ḥizb-e Islami (Islamic Party) and Jamiat-e Islami Afghanistan (Afghan Islamic Block);

– or even that, again in Pakistan, arise characters as Mawlānā Sufi Muḥammad, the founder ofTehrik-e-Nafaz-e-Sharī’at-e-Moḥammadi (Movement for the Implementation of Islamic Law), the Deobandi Mawlana Haq Nawaz Jhangvi, the founder of Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan, the Wahhabi from Punjab Riaz Basra, founder of Laškar-e-Jhangvi, all of them major players in the Asian regional policy in the last few years, whatever you think about their behavior.

Next May 11th, three main parties will contend for 342 seats in the National Assembly:

- the Pakistan People’s Party, led by Bilawal Bhutto Zardari (heir to the political tradition of his mother Benazir Bhutto and his grandfather Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto and, above all, son of the President of Pakistan Asif Ali Zardari), a socialist-oriented party which has its stronghold in the rural Sindh province and in the southern Punjab areas;

- the faction of the Pakistan Muslim League led by Nawaz Sharif (twice Prime Minister from 1990 to 1993 and from 1997 to 1999), a moderate Islamic movement receiving support particularly in the urban areas of Central Punjab;

- Pakistan Tehrik-e-Insaf (Pakistani Movement for Justice), hosted by the former cricketer Imran Khan, a democratic-nationalist and Islamic movement to be regarded as the greatest opponent of the Muslim League of Nawaz.

But, due to the recent ban on the use of religion in the election campaign, interest has also focused on the voting behavior of political groups more properly Islamists, such as:

- Jamā‘at-e-Islami (Islamic Block) of Syed Munawar Ḥasan, a theo-democratic Islamist party opposed to liberalism, socialism and secularism;

- the faction of the Deobandi Jamā‘at ‘Ulemā’-e-Islām (Assembly of Islamic Clergy) led byMawlānā Fazal-ur-Rehman, a socially conservative party, but with moderate socialist orientation in Economics, that was an ally in coalition with the Pakistan People’s Party in the 2008 elections;

- the faction Quaid-e-Azam of the Pakistan Muslim League, led by Chaudhry Shujaat Ḥusayn, a nationalist party that acts as a major ally of the Pakistan People’s Party in Punjab and Balochistan and that in the past years supported the General Musharraf’s regime;

- Muttahida Deeni Mahaz (United Religious Alliance) of Mawlana Sami-ul-Ḥaqq, an alliance of six religious parties opposing the secular politics of the current government.

Nevertheless, among the Islamist forces, Tehrik-i-Tālibān Pakistan, the Taliban Deobandi movement born at the end of 2007 and banned in 2008, has warned citizens from participating in the elections.