Among mutual accusations of loyalty to global and regional potentates, the movements emerging in the post-Saleh era are weaving a texture of new institutional powers. Or maybe…

by Glauco D’Agostino

Yemen established its identity on both tribal and religious bases. Its 168 tribes represent 85% of the population, since they are rooted in the ethnic Arab Qahtani and Arabized Adnani groups, the former in the South, the latter in the North, Center and West of the country. In turn, Yemeni religious identity, traditionally very heartfelt in a State basing its legal system on the Sharī’a law, comprises two constitutive elements:

- the Sunni one of Shāfi’i or Salafi juridical schools, followed by most of the population, spread in the South and Southeast and along the coasts of the country;

- and the Zaydi Shiite one (known as Hādawi in Yemen), followed by some nine million people (35% of Yemenis), mainly located in the North and Northwest.

Other minority groups are the Ismaili and Twelver Shiites (the latter of Iraqi origin), the Ibadis from Oman and the Saudi Wahhābis. Historically, there was also a Jewish community, mostly emigrated to the State of Israel after it was formed in 1948, whilst an indigenous Christian community is missing.

Currently, though at a popular level the Islamic faiths distinctions don’t pose any barrier between the respective religious communities, the development of political events is leading to a conflict that many analysts regard as dangerous not only for the very existence of Yemen, but also for international balances in the Arabian Peninsula. Obviously, this is a concern mainly expressed by those who estimate a value the institutional stability arising during the past century from the impairing frameworks by the world powers.

Last October 16th, al-Qāʿida-linked militias have clashed with Zaydi Ḥūthi military units in central Yemen, resulting in ten casualties; and the previous week, the same militias have made a devastating suicide bombing against a Ḥūthi rally in Ṣan‘ā’ (in the picture above two images of the old city), killing nearly fifty people. Al-Qāʿida in the Arabian Peninsula, born from the merger of the Yemeni and Saudi qāʿidist formations, considers the Ḥūthis as heretics (since they are Shiite) and as pawns in the Ayatollahs’ hands, especially since their leader Ḥuseyn Badr ed-Dīn al-Ḥūthi, murdered in 2004 in a clash with government military forces, had been suspected of introducing new methods of political activism from Iran. Of course, the Ḥūthis reject this charge, introducing themselves, instead, as a political force defending religious freedom and social justice.

Whatever it is, it’s undeniable the Ḥūthis are on a political rise, and since September 21st have been gaining a controlling influence over government (action endorsed, too, by the UN envoy’s proposed Agreement), by prompting President ‘Abd Rabbuh Manṣūr Hādī to change the government layout according to their directions, and by serving as advisers to President for future options.

The beginning of this political acceleration has had its source in the popular protest against the International Monetary Fund injunction to Yemen for cutting fuel subsidies in order new loans to be granted. In the background, however, a decades-long conflict between Zaydi rebels and government authorities since the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen fall in 1962, which had resulted in the end of local Shiite Imamate after a thousand years. And, yet, a proxy confrontation entrusted to local forces by the major powers and regional potentates, historically vying its territorial quality:

- the use of economic resources;

- control of the Red Sea and Indian Ocean commercial shipping (especially for oil) coming from and bound for Suez Canal;

- military-strategic control of the region, regarded as an access to the Arabian Peninsula and to some of the key geopolitical areas of the world.

Following the arrival of Ḥūthi militias, first in the ‘Amrān Governorate on July 8th, later in the capital Ṣan‘ā’ on August 24th in a peaceful support of popular protests, and after some government concessions are deemed to be insufficient, on September 18th the Ḥūthi military escalation has begun: on 20th they have conquered State TV and 21st the Iman University and the First Armored Division military base of General ‘Alī Mohsen Saleh al-Ahmar, the man who had led the 2004-2010 six military campaigns against Ḥūthis. By then, both the Army and several ministers said they didn’t want to fight the Ḥūthi initiative, by avoiding offering resistance to the Central Bank siege, up to the time when the Ministry of Interior ordered its units to cooperate with the rebels. A move feeding suspicions up on existence of a secret agreement between President Hādī and the Ḥūthi movement for scaling a power order corresponding to a different political era.

The Ḥūthi surge has a clear political valence against the State establishment subjects that, even after the 2011 departure of President `Alī ‘Abdullāh Saleh (leading the highest institution since 1978), have continued to effectively run the Yemeni politics: among them, the General People’s Congress, the Saleh’s secular nationalist party, which had won 80% of the Parliament seats in the 2003 last election; the aforementioned General ‘Alī Mohsen Saleh al-Ahmar, close to the Muslim Brotherhood and a distant cousin of the ousted President; the al-Ahmar family (different from the previous point’s General), dominating the northern tribal Hashid Confederation, not the largest, but certainly the most powerful of the Yemeni Confederations, being inter alia the one which former President Saleh belongs to.

One of the outcomes of National Dialogue Conference, which began March 18th, 2013 and ended January 24th of the current year, has been the agreement in order to turn Yemen into a federal State of six regions, four in the North and two in the South, giving Ṣan‘ā’ a special status of capital out of any regions. That Conference was part of the Gulf Cooperation Council Initiative to chart the post-Saleh transition of power and was subsequent to Resolution 2051 of the UN Security Council, which outlined its process. Under the direction of President Hādī and supervised by a UN representative, the Conference had admitted participation in the work not only to the General People’s Congress and its allies, to the pan-Arabist Yemeni Socialist Party and to the Nasserite Unionist People’s Organisation, but also to the separatist Southern Movement, the Zaydi Ḥūthis and their military wing Anṣār Allāh, and the islamist Yemeni Congregation for Reform (known as al-Islah and affiliated to the Muslim Brotherhood).

However, January 21st the Ḥūthis had left the Conference, following the assassination of one of their Conference components by Salafi elements, whereas Ḥūthis and Salafis warring in the northern Ṣaʿda Governatorate. By doing so, the Ḥūthis had caused the shutdown of Conference, closed with the signature of a document in favor of a federal Yemen, which, if implemented, would weaken the quasi-independence situation achieved by Ḥūthis in the city of Ṣaʿda in 2011, with its Governatorate back under federal control, but leaving it without outlets to any Red Sea ports. That would explain the pre-emptive Ḥūthi move of the Ḥudaida port seizure in mid-October, which could herald the break-out towards Bāb al-Mandab and the resulting shipping control of the namesakeStrait.

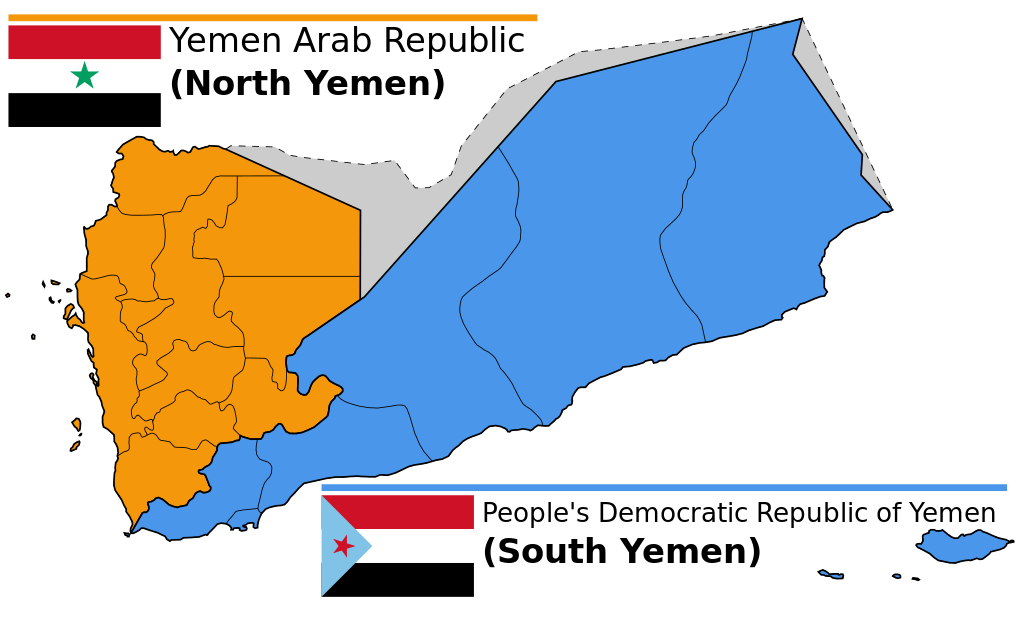

A secessionist threat by the Southern Movement has to be added to the Zaidi restlessness in the north. The former appears as a cluster of anti-governmental organizations heirs to the factions opposing during the 1994 civil war the historical northern dominance. In fact, after the 1990 unification of northern Yemen Arab Republic and southern People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen, with Saleh as President, the new government had been established on the basis of a compromise between the two ruling parties in the prior States, that is, the General People’s Congress in the North and the Yemeni Socialist Party in the South; but in 1993 ʿAlī Sālim al-Bayḍ, the Vice President representing the southern populations, had accused the government of marginalizing the South, resulting in his come back to Aden with intentions of defiance towards Saleh. This had paved the way for participation in the government of al-Islah Islamist party, whose founder is former mujāhid of the anti-Soviet Afghanistan war Shaykh ’Abdul Majid az-Zindani. The al-Islah leader, when in May of 1994 a civil war had begun, had condemned the southern secessionist movement as a “foreign conspiracy”, by stressing the fact that the Marxist Soviet-inspired ideological origin of the resigned southern leaders from government would have demanded an answer in terms, as well as military, of political loyalty to the Islamic basics of the Yemeni State. Aden had fallen in July of that year and former President al-Bayḍ had found refuge in Oman, but the “southern issue” in Yemen would have continued to be a problem for the Ṣan‘ā’ government, even though not longer a danger. At least so far!

Actually, the 1994 crisis had its roots primarily in an economic yet unresolved issue; and particularly in the income distribution from oil resources. These resources are located mostly in the South, but their revenues are centralized, without the government involving the influential tribal authorities of the territory, and above all without a fair sharing (according to southern claims) in terms of financial returns for development. Added to this are political claims regarding freedom of presenting unrestricted secessionist options under the patronage of some movements.

The Ḥūthi and southern questions have been for the last decade undermining the credibility, if not the legitimacy, of a government weakened in its prerogatives to represent the institutional power, for the benefit of a representativeness strengthening of civil society, not least its tribal and religious traditional components. The reasons can be identified in just a few determinants, such as:

- a widespread corruption in all sectors of society, without the successive governments (suspected of being part of this ethical drift) have been able to fight it;

- perception of the institutions as an expression of Saudi and North American interests rather than national ones, with an obvious depletion of resources and of Yemenis’ economic conditions, and responsible for increasing social inequality;

- a security policy previously regarded as ambiguous (and today perhaps constantly evolving), now accommodating with the USA “ally” up to the point of enabling on its sovereign territory several military actions against al-Qāʿida damaging domestic and international law, now militarily fighting Islamists and opposition groups which may actually represent a political counterpoint to the al-Qāʿida military power.

Particularly the latter point makes clear the confusion which, in truth, belongs not only to Yemeni government, but today also to the international players. Therefore, al-Qāʿida is the enemy and the international community wants to fight it. The Zaydis do so, but, since they are Shiite, could be Iran allies and this is not good, nay for some they are terrorists. But Zaydis are countered by Saudis, who are Wahhābi (as al-Qāʿida chromosomes are) but US allies. Al-Islah Muslim Brothers oppose Zaydis as Saudis do, but the latter fight them and in their homeland Muslim Brotherhood is illegal, nay deemed useful to terrorism, even though its senior member Tawakkol Karman received the 2011 Nobel Prize for Peace. And the United States? Don’t worry. As usual, it’s up to it giving report cards and “terrorism” licenses. Now this one, now that one, according to contingencies. And between a punitive action and the next one. But it’s needless to ask it for a long-term strategy!

The truth is the Islamic world representation is sometimes very complex and it’s not easy to reproduce it according to geo-political and alliance patterns which XX century Western observers and analysts were used to. This explains the macroscopic evaluation “errors” about men and organizations made by many, holders of Chancelleries functions in primis. Enough to mention the cases of Qaḏāfī, Ṣaddām Ḥusayn, bin Lādin, who have been celebrated at certain stages of history and vilified in others; or the Muslim Brothers, Ḥizb Allāh, Ḥamās, sometimes regarded as subversive or even terrorists movements and other times widely and internationally recognized when they joined governments of their respective countries.

Back to Yemen, how many remember that former President Saleh is a Zaydi Shiite and, when the Ḥūthis challenged his power, tried to oppose his religious identity to an alleged Shafi’i plot in an extreme attempt to save himself? Who in the 33-year President’s rule has raised objections on his religious beliefs, perhaps in order to speculate on his unconventional political work? Why doing so today towards a Zaydi political component on which the world has cast a shadow, by politically aligning with the international balances?

The Zaydis not only are today an integral part of Yemeni society, but they have forged its history and character, that is the core components of its identity. Since the time of its first Imām Hādī ilā al-Ḥaqq (Guide to Truth) Yaḥyā bin al-Ḥusayn more than 1100 years ago, the Imamate has been the religious and political reference of Yemenis (as it has been recognized in its legitimacy also because of Imām lineage from ‘Alī ibn Abū Ṭālib via his son Ḥasan), though not always it had control of the entire territory and hardly ever of the eastern territory of Ḥaḍramaut, which has remained loyal to Shafi’i Sunni Islam and Sufism. The identity problem of the South, which brings with it the colonial heritage of the Aden Protectorate (in the map below its extension before 1959), comes also from this evidence.

The issue of the actual political exercise of a no longer infallible Imām, already set since the eighth century by the Zaydis at their doctrine birth, is the aspect that most distinguishes them from Twelver Shiites and puts them in opposition to the Ayatollahs’ Iran. It’s therefore difficult assuming a convergence on a doctrinal level, as could not be excluded a rapprochement on a political level. But, while validating this hypothesis, an Imamate revival even in its political dimension (which has often been assigned to the Zaydi intentions by the Yemeni governments) could never be endorsed by the Iranian Supreme Guide, who is the hidden Imām’s representative.

Ultimately, political Islam plays today a founding role in the new Yemen, not yet stabilized after the tensions followed to Saleh’s removal. These are the main areas aggregating Islamist militants:

- the Muslim Brothers, represented in Parliament by the Yemeni Congregation for Reform and in the society by a strong social component in the economic, military, tribal fields, as well as of diplomacy and the communication world. Since they have been the major allies of President Hādī and his party, they have come into conflict with him as a result of decision to admit the Ḥūthis in the National Dialogue Conference. After the taking of ‘Amrān Hashid stronghold exactly by Ḥūthis and a resulting weakening of Ahmar family, its ally, the role of al-Islah party is now downsized compared to the past;

- the Ḥūthis, which we have been widely talked about earlier. Since they never hit Western targets, analysts don’t consider them a threat outside Yemen. Led by Shaykh Sayyid ’Abdul-Malik al-Ḥūthi, a historic leader Ḥuseyn Badr ed-Dīn’s younger brother, they blame government for failed development and abandonment of Shiite-inhabited areas, which are among the poorest in the country;

- the Salafis, articulated in three main branches: the one referring to Egyptian Shaykh ‘Abdur-Rahman ‘Abdul-Khaliq’s philosophical movement; the radical one, inspired by the Athari thinker Muqbil bin Hādī al-Wadi’i, in turn influenced by Saudi Juhaimān al-ʿUtaibī; and the jihādist one of Syrian Shaykh Moḥammed Srour;

- Jamāʿat Anṣār ash-Sharīʿa, established in 2009 as an aggregation of various insurgent movements, including al-Qāʿida in the Arabian Peninsula, and mainly active in the South. Headed by Emir Nāṣir ‘Abd el-Karīm al-Wuhayshi (also known as Abū Basir), between 2011 and 2012 the organization has maintained control for over a year of the important harbor city of Zinjibār, on the southern coast, and other key towns in the area, all of them declared as Islamic Emirates.

The upcoming presidential elections are on next February Yemeni agenda. Quite a challenge for incumbent President Hādī, in extension after a two-year mandate received by 2012 polls! A challenge not so much towards whomsoever dares to vie in 2015 (if the date will be confirmed), rather to the need for change strongly expressed from the country bowels, to the point of evoking Imamate restoration and a secession threat by a substantial part of the territory. Politics must give these needs some convincing answers, unless it prefers choosing the way of an impossible continuity with the arrangements of the past. In this case, it will be chaos, which, of course, the generous people of Yemen do not deserve!