by Glauco D’Agostino

The first anniversary of the Ukrainian crisis worsening (war operations had already begun nine years ago) still registers two opposing fronts: that of Western leaders, assertive and insistent on the need for a just war as a resolution of international disputes, versus a pacifist front, incessantly committed for a diplomatic settlement action despite the ideological differences. An Asian coalition certainly not homogeneous stands out today as an international player proposing itself as a mediator, a role belonging to the great powers until recently played by the United States of America, which instead is currently part of the conflict together with the subordinate European allies. Xi Jinping’s peace proposals from China presented today are evidence of this not just on a tactical level but as a long-term strategic agenda for global governance. A hard blow for the arms producers represented in the institutions and for the NATO gas-producing countries that have made and still make enormous profits from the sanctions. Islamic World Analyzes features the following geopolitical analysis by Glauco D’Agostino, first published this month in “Geopolitica. Revistă de Geografie Politică, Geopolitică şi Geostrategie,” Anul XX, nr. 96-97 (4/2022) “CENTRE DE PUTERE AXE ŞI FALII GEOPOLITICE“.

Abstract

The world seems to be heading towards a new multipolar order, or maybe it already is. The driving force behind this process is undoubtedly China. Signs in this sense have been present for many years, though the still immature times and wise prudence advise against accelerations on the subject. The thorniest perspective problem is the placing alongside the dollar of other competing currencies in international transactions. Also, the Kremlin calls for multilateralism as an instrument to rebalance the world order. Thus, the challenge for a reform of the world’s financial architecture is open, this time with the joint competition of China, Russia and India. The Ukrainian crisis is evidence of an alleged world unitary political management with no regard for the consequences in terms of economic and monetary management on the “others.” The vastness of the types of sanctions imposed mainly by the United States led to a substantial global protectionist economic regime and the world divided and polarised.

Xi Jinping’s “New Type of Security Partnership” for the Asia-Pacific region puts no restraints or fences, asks for no restrictive loyalties, and goes beyond any politico-ideological barriers and alliances. At the same time, China is annoyed by the US interventionist approach in what Washington calls the Indo-Pacific. In the background, the thorny question of Taiwan. Beijing’s diplomatic strategy aims to use its influence within Asian supranational bodies to which it belongs, both the interconnection with other institutions concerning Southeast Asia and the Pacific, ASEAN first. The role of India is decisive in this picture, as in 2023, it will chair the SCO and G20 Summits. More and more states join multilateral mechanisms involving now international relations. SCO and EAEU are institutions conceived as a geopolitical strategy for Asia. The BRICS claim a decision-making space for emerging countries, where the Asian contribution is decisive. The BRI implements a mechanism of trade and development agreements free from constraints. Despite centuries-old internal disputes, Asia seems to become a geopolitical player capable of internalising domestic conflicts and overcoming them because of common advantages.

Keywords: Asia, multipolarity, multilateralism, China, Russia, India, Ukraine, United States, sanctions, protectionism, Asia-Pacific, Indo-Pacific, BRICS, SCO, EAEU, BRI.

***

Introduction

The Western recklessness in understanding the inadequacy of the world governance system in the face of changes in international arrangements is surprising. Even more bewildering is the inadequacy of E.U. diplomacy, which, while weakened by Brexit, also closes its doors to Turkey, a NATO ally, and even rejects the Russian Federation as a terrorism state sponsor. The result is Great Britain returning to the arms of its historic ally (Washington, indeed not Brussels) and Ankara and Moscow increasingly looking to Asia. Beijing says thank you.

The geopolitical bloc forming in Asia has been under construction for at least a decade. Still, today it finally finds the room for manoeuvre that the weakening of the Euro-Atlantic economic and political systems allows and indeed causes with its now obsolete ideological rhymes. For the countries of the Waning Sun, a geopolitical adversary is not a competitor to overcome loyally according to the rules of the free market they claim to be inspired by. Simply a contender, as not explicitly deemed an enemy, is never too democratic and never fully respects the human rights of which Washington and Brussels are the sole guardians. Too bad the colonial and war past disproves this claim, but, above all, has perpetuated apparatuses based on the coercion of military power through binding alliances also in terms of geo-economic choices.

In this framework, the countries rejected by the world order power system gear up not to counter the ruling military supremacy (objectively unbeatable on this level) but to achieve the consensus of the “willing” through aggregations open to collaboration and never forced by bonds of loyalty. This is because some of these outcast countries have meanwhile acquired knowledge and skills in other fields of human action (finance, technology, communication) and are trying to understand the 21st century needs more realistically. It is an attempt, of course, and not free of contradictions. The West remains the bulwark of preservation of a power it still holds. But perhaps it does not realise that its hinges are creaking because obsolete vis-a-vis a way of understanding international relations coming and creeping over from the East to involve those subjects not represented by an exclusive and sectarian standard of governance.

Beyond the above assessments acting as a general framework, the following considerations are quite explicative of the alignment processes, especially in Asia as the main theatre of the current and future geopolitical dispute.

Multilateralism as an alternative to the model of governance

The world seems to be heading towards a new multipolar order, or maybe it already is. The driving force behind this process is undoubtedly the People’s Republic of China, which does not intend to be the pivot of this new order because multipolarity does not envisage a unilateral replacement of the shut rule of sovereign power. It would be a contradiction in terms. Therefore, are we at a paradigm shift in the direction of the planet’s destinies? It could be. There are many conservative thrusts, and analysts are divided on the matter. However, signs in this sense have been present for many years. With the assumptions of principle (unrealistic or not), messages conveyed that feel an already existing potential, though the still immature times and wise prudence advise against accelerations on the subject.

Following the 2007-08 global financial crisis, the five emerging economies of as many developing countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa), members of the G20 intergovernmental forum that had given birth to the aggregation called BRICS, immediately arose as an alternative to the governance pattern of the G7 formed by countries gathered around the ideological values of pluralism and democracy. In practice, a contestation of leadership, mainly concerning the structural limits of the response given by the seven most advanced economies towards the consequences of that crisis that have not yet been overcome today.[1] Conversely, still today, the BRICS renovate their trust in the G20 while expressing the conviction “that it is imperative to strengthen macro-policy coordination in driving the world economy out of the crisis.”[2]

Straight to the heart of the challenge, the thorniest perspective problem is the placing alongside the dollar of other competing currencies in international transactions, in any case leaving out the emerging realities of cryptocurrencies without intermediaries in peer-to-peer mode. Already in the 7th Summit of the BRICS Heads of State and Government, held in the Russian city of Ufa, Bashkortostan, on July 8th and 9th, 2015, the final declaration assumed to recognise “the potential for expanding the use of our national currencies in transactions between the BRICS countries. We ask the relevant authorities of the BRICS countries to continue discussion on the feasibility of a wider use of national currencies in mutual trade.”[3]

SCO Meeting of the Council of Heads, Samarkand, Uzbekistan, September 15-16th, 2022 (Source: News 18)

The current importance of that summit is also underlined by Xi Jinping’s appeal for a “strategic and long-term perspective”[4] to two other regional cooperation organisations playing a decisive role in Asia: the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO)[5] and the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU). In turn, Vladimir Putin added at the time: “There is no doubt – we have all necessary premises to expand the horizons of mutually beneficial cooperation, to join together our raw material resources, human capital and huge consumer markets for a powerful economic spurt.” Today the Kremlin calls for multilateralism as an instrument to rebalance the world order while appealing to the United Nations to limit the Western bloc’s influence power as a weapon of ideological and political pressure.

The previous quotes also help to make clear that Moscow’s current apprehensions about in-force finance and international trade management have well-dated[6] origins and that the pandemic and the Ukraine war have only exacerbated its stance.

On April 25th, 2022, at the Innoprom Exhibition in Taškent, Uzbekistan, the Russian Minister of Trade and Industry Denis Valentinovič Manturov (also Deputy Prime Minister since the following July) stated as follows: “What’s happening in the whole world in the past two years, firstly, is the impact of the pandemic. What’s happening in the global economy today gives us an indication of how we need to restructure our logistics, our production cooperation, in what areas we need to develop our economies. This is also, as was commonly said before, de-dollarization. Now we have also added de-euroization, meaning a transition to our own currencies in order to be as independent as possible in terms of mutual settlements in reciprocal deliveries of our products and in mutual cooperation … We see what is happening now in Western Europe, in the United States, it’s pretty much hyperinflation. No one remembers such a thing, or at least this has not happened for a long time, more than 30 years, in these countries. Prices are rising fast for exchange-traded commodities. This is having a strong impact on the development of sectors of industry and the economy in general.”[7]

The propulsive role of BRICS, SCO and EAEU

Thus, the challenge for a reform of the world’s financial architecture is open, this time with the joint competition of China, Russia and India.[8] The cause of the speeding up is the Western boycott of Moscow regarding the system of financial transactions and payments (the SWIFT messaging network); the strategic tool to be adopted is diplomacy towards the BRICS countries, emerging economies together accounting for 18% of the world trade and 25% of foreign investments.[9] In 2017, at the 9th BRICS Summit in Xiàmén, Xi Jinping proposed the group expansion to other countries that shared its objectives, suggesting the diplomatic work for a new, larger grouping, what will be called BRICS+. This yet virtual player advocated not only the close cooperation between SCO and EAEU already solicited at the Ufa Summit but one the institutions such as the Southern Common Market (Mercosur), the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) and the Southern African Customs Union (SACU). When Putin chaired the 12th BRICS Summit held online on November 17th, 2020, he called for the extension of the commercial BRICS Pay system to all BRICS+ (Zongyuan, 2022).

The appeal of Xi and Putin has aroused actual interest in many countries. Among them:

- As regards the BRICS:

- Argentina and Iran applied for admission before Algeria did in November 2022;

- On June 23rd, 2022, Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Egypt showed an interest in joining them at the China-chaired 14th Summit, which played on the issues of cooperation on local currencies, logistics and cross-border e-commerce.

- As regards the SCO:

- In June 2022, Iran, which will become a full member in 2023, asked members to create a single currency for all Organisation countries;

- Last September, Belarus, as an observer country, formalised its request for full access;

- Again in September, Turkey announced by the mouth of President Erdoğan its forthcoming application for membership,[10] thus becoming the first NATO country to join a China-led organisation;[11]

- Qatar, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia have been accepted into the same organisation as “Dialogue partners” (Varma, 2022).

India, which concerning sanctions, is increasing its oil import from Russia, seems intent on using the rénmínbì for related transactions as the Chinese currency has been in April 2022 the fifth most active currency by value for worldwide payments, according to SWIFT data (Buck, 2022). New Delhī has also been non-committal about a G7-countries proposal for a price cap on the Russian oil import as a means of hurting the Russian economy.

Even the New Development Bank (NDB) can be considered a relevant regional aggregation tool to upgrade local currencies. After India proposed it as a multilateral development entity among the BRICS countries, the bank has been active since 2015 and is based in Shànghǎi. It immediately declared itself open to collaborating with other institutions on the issue of environmental protection.[12] Above all, its composition has expanded, in 2021 welcoming Bangladesh, the United Arab Emirates, Uruguay and Egypt among its members. Its operations have allowed funding significant projects, including the Jiangxi Natural Gas Transmission System Development in China, the Bihar Rural Roads and the Madhya Pradesh Major District Roads II in India, The Development of Water Supply and Sanitation Systems in Russia; and the connection of 592 thousand families to water supply and 727 thousand to wastewater collection networks has just been approved in the State of São Paulo, in Brazil.[13]

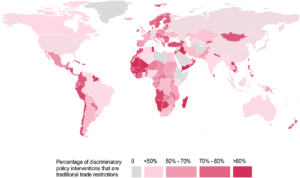

Protectionism and sanctions vs openness to the market

The game seems to play out over sanctions and protectionism on the one hand and openness to the market and liberalisation on the other.[14] Incredibly, the democratic and liberal West, along with its Asian allied offshoots, lines up with the first stance, while the so-called emerging countries, followers of some leaders of a formally communist absolute power, do with the second one. A paradox of history but a fact we live in the present days, as contradictory as you like, but with which we are called to come to terms. It means the balance in a globalised world will only be found by alternative models of managing exchange processes compared to those that prevailed for 80 years following WWII.[15]

Wáng Yì, Chinese State Councillor and Minister of Foreign Affairs (left), meets in Phnom Penh with Hŭn Sên, Prime Minister of Cambodia, October 12th, 2020

The war in Ukraine appears to be only the effect of a process of destructuring the world order, which began with the end of the Soviet Union in 1991 and continued with the admission of the People’s Republic of China to the WTO in 2001, the subversion of the Islamic world and the NATO eastward expansion. One would say the propelling mechanism of change located in the West, in search of external legitimisation for its overwhelming power that has been strangling it for at least 20 years and condemning it to existential solipsism and the slavery of the representation of a single thought, it’s own. And yet, its obstinacy in playing the ideology card in geopolitics determines the collapse of its power when the other side of the world, beyond doctrinal formulations, seeks horizons of livability and stability so far precluded by external economic and financial dependence. “Asia’s time has come in global governance,” the Chinese State Councillor and Minister of Foreign Affairs, Wáng Yì, suggested a few months ago on the margins of the 5th Session of the 13th National People’s Congress.[16]

Therefore, the Ukrainian crisis is evidence of an alleged world unitary political management with no regard for the consequences in terms of economic and monetary management on the “others,” those who did not have access to that management, as it was not shared.[17] “All States must have equal access to the right to development,” a Sino-Russian Joint Statement set down on the margins of the Beijing Winter Olympics.[18]

The war in Ukraine uncovers these mechanisms by the sanctions on Russia, including secondary extraterritorial ones, the first of this magnitude against a member country of the UN Security Council: economic, financial, commercial, military, diplomatic, sporting, followed by personal and corporate sanctions, and with the burden of freezing bank accounts and properties.[19] In this case, sanctions are an instrument that, regardless of the reasons, is used to try to isolate Russia on a geopolitical level. The result is strengthening the pole based on the three giants of Asia and built on the connected multilateral institutions.

Discriminatory policies interventions that are traditional trade restrictions (Source: Springer Link on Global Trade Alert data, 2018)

The vastness of the types of sanctions imposed mainly by the United States, which until then had concerned only countries of limited geopolitical weight, led to a substantial global protectionist economic regime by limiting the flows of goods, services and people and the world divided and polarised according to the attitude to the sanctions against Moscow: on the one hand, those in favour, on the other, those against, including China, Iran, Syria, North Korea, Myanmar, Venezuela and Cuba, themselves previously hit by Western sanctions (Ekman, 2022). The vote in the UN General Assembly for the resolution demanding a complete withdrawal of Russian forces and a reversal of its decision to recognise the self-declared People’s Republics of Donetsk and Lugansk pointed out a splitting line between the countries. Among the 40 members that pronounced against or abstained, only two, apart from the Russian Federation, are European countries. The remaining are 18 African (out of 47 African Union voters), 15 Asian (including 2 APEC and 2 ASEAN countries), and 4 Latin American.[20] Within the BRICS, only Brazil approved the resolution while criticising the indiscriminate sanctions. As for other regional organisations of which Russia is a member, all SCO (except for absent Uzbekistan) and EAEU countries have shown solidarity with Moscow, either by abstaining or voting against the resolution as in the case of Belarus.

China, the BRI and the Central Asian strategy

A cross of the preceding data shows three powers, such as China, Russia, and India, aggregating well beyond ten countries of the BRICS and SCO combined membership, undertaking a sort of teamwork Beijing names “New Type of Security Partnership”[21] for a policy of “building friendship and partnership with neighbouring countries.” In particular, the strategy Xi Jinping adopted in 2017 for the Asia-Pacific region overturns the practice of alliances based on conflict, wishing that “Countries may become partners when they have the same values and ideals, but they can also be partners if they seek common ground while reserving differences … Major countries should treat the strategic intentions of others in an objective and rational manner, reject the Cold War mentality, respect others’ legitimate interests and concerns, strengthen positive interactions and respond to challenges with concerted efforts. Small and medium-sized countries need not and should not take sides among big countries. All countries should make joint efforts to pursue a new path of dialogue instead of confrontation and pursue partnerships rather than alliances.”[22]

It is an open and flexible strategy putting no restraints or fences and asking for no restrictive loyalties while projecting itself towards mutual inclusion and consultation beyond any politico-ideological barriers and alliances.

The most effective tool China put in place in this direction is the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), where 147 countries have signed a legally non-binding Memorandum of Understanding, according to the updated dossier by the Green Finance & Development Center of the Fanhai International School of Finance (FISF) at the Fudan University of Shànghǎi.[23] Cumulative BRI commitment, amounting to US$ 932 billion, stands out among the study’s main conclusions while specifying the investments in gas and oil in 2022 in the BRI countries were about 80% of Chinese energy investments abroad, including the largest ones in Saudi Arabia and Algeria. One should mark here that both countries are among those who are interested in joining the BRICS, and Algeria has already formally submitted the relevant application last November. As for Saudi Arabia, Chinese investments will increase the synergy between the BRI and Vision 2030, which inspires Riyāḍ. A prime example of positive interaction. In fact, regarding investment projects, the consortium led by EIG Global Energy Partners, which since June 2021 has been controlling the Aramco Oil Pipelines Company,[24] has made the Silk Road Fund and the China Merchants Bank chief investors.

President Vladimir Putin at the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum (SPIEF), June 17th, 2016

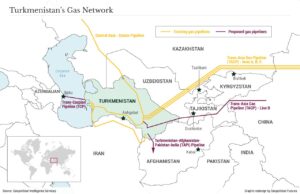

Putin is also playing his cards by targeting initiatives on the security of the export of Russian energy resources.[25] Since 2017, with the first meeting of the SCO Energy Club under the presidency of Erdoğan’s Turkey, the Kremlin has opened up to some observers and dialogue partners who are functional for transporting energy to China, Japan, Korea, India and Europe, the markets with the most significant demand. Thus, it establishes “good neighbourly” relations with countries along the routes of pipelines originating in Russia, such as Mongolia, Afghanistan, Iran, Sri Lanka, and Belarus.[26]

Turkmenistan’s gas network (Source: Stefan Hedlund, Geopolitical Intelligence Services, March 25th, 2019)

Beijing pays the same attention to the countries of Central Asia, having since 2010 become their first trading partner to the detriment of Europe. Since 2020, it has launched the C+C5 meetings (China plus 5 Central Asian countries) to contain the effects of the similar US C5+1 initiative.[27] China thus moves from bilateral trade relations to a level of multilateral political cooperation,[28] among other things also including Turkmenistan, a traditionally neutral state at the time and therefore outside the SCO and EAEU. Indeed, Moscow does not welcome some Chinese initiatives in Central Asia, including the Free Economic Zone within the SCO and the creation of dedicated banks and funds for development (Pandey, 2022). However, even recently, on the sidelines of the 7th China-Asia-Europe Expo held in Ürümqi, Xīnjiāng, the 2022 Silk Road Economic Belt Core Area Development Summit Forum addressed the topic of a potential Free Trade Zone with SCO participation centred on Xīnjiāng as a hub. The initiative is linked to the BRI promotion in Central Asia and Europe through the numerous existing international freight train services reaching as far as Germany.[29]

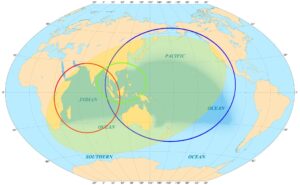

Indo-Pacific or Asia-Pacific?

If true that Beijing pushes west for greater regional security or for a more profitable connection with the energy supplier countries it urgently needs,[30] it is showing even greater interest in the Asia-Pacific areas. China is annoyed by the US interventionist approach in what Washington calls the Indo-Pacific through geopolitical tools such as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) between the US, Japan, India and Australia, the AUKUS Trilateral Pact between Australia, the UK and the United States,[31] and the Summit for Democracy[32] which emphasised the fight against autocracies and respect for human rights in an anti-Chinese perspective, with speeches by anti-government activists from Hong Kong. In the background, the thorny question of Taiwan.

Again Chinese Minister Wáng Yì says: “US leaders and senior officials have stated that the US has no intention to seek a new Cold War or change China’s system, that the revitalization of US alliances is not anti-China, that the US does not support «Taiwan independence», and that it is not looking for conflict or confrontation with China. Regrettably, however, these statements are just verbal assurances and have yet to be put into practice. The reality we have seen is this: the US is going to great lengths to engage in intense, zero-sum competition with China, it keeps provoking China on issues concerning our core interests, and it is taking a string of actions to piece together small blocs to suppress China … This is by no means some kind of blessing for the region, but a sinister move to disrupt regional peace and stability” (Embassy of the PRC in the US, 2022).

Reference to the Cold War occurs in many documents. “The sides oppose further enlargement of NATO and call on the North Atlantic Alliance to abandon its ideologized cold war approaches,” the 2022 Sino-Russian Joint Statement explicitly says, echoing the 2017 China White Paper. This highlights that Moscow is interested in Beijing’s opposition to NATO expansion. Likewise, Beijing is seeking Moscow’s consensus on the issues of Taiwan, the Pacific, and the trilateral security partnership AUKUS posing “serious risks of nuclear proliferation” (Office of the President of Russia, 2022).

China intends to fend itself against the U.S. “provocations” according to the principles of the Global Security Initiative[33] launched by Xi Jinping on 21 April 2022 at the annual Bó’áo Forum for Asia, a non-profit organisation that since 2001 has brought together 28 countries from Asia and Australasia. During that meeting, the Chinese President expressed his opposition to “unilateralism … double standards, the abuse of unilateral sanctions and «long-arm jurisdiction»,” and the need to avoid “building one’s own security on the basis of other countries’ insecurity.”[34] Therefore, Beijing moves on to counterattack with the weapons of diplomacy. For example, a few days earlier, it signed a security pact with the Solomon Islands, South Pacific, allowing China to “make ship visits to, carry out logistical replenishment in, and have stopover and transition in Solomon Islands.”[35]

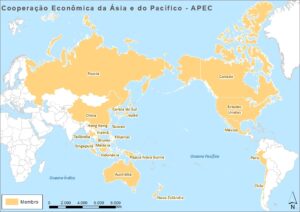

But Beijing’s diplomatic strategy aims to use its influence within Asian supranational bodies to which it belongs, such as APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation), CICA (Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia) and the Beijing Xiāngshān Forum, both the interconnection with other institutions concerning Southeast Asia and the Pacific, such as the political-economic union ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) through its related mechanisms (ASEAN+6, East Asia Summit-EAS, Regional Forum-ARF, Defence Ministers Meeting Plus-ADMM+, Expanded Maritime Forum-EAMF).

At the virtual 2020 ASEAN Summit hosted by Vietnam, 15 Asia-Pacific countries signed a free trade agreement named Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), the largest trade bloc in history, which includes all ASEAN countries but also, besides China, historical Washington’s allies, such as Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand. This is a diplomatic success for Beijing’s soft power as it significantly expands its network of commercial partners throughout the Pacific (Ekman, 2022). Eswar Prasad, a professor of economics and trade policy at Cornell University and the former head of the International Monetary Fund’s China Division, comments: “The trade pact more closely ties the economic fortunes of the signatory countries to that of China and will over time pull these countries deeper into the economic and political orbit of China.”[36]

The role of India is decisive in this picture. Even though out of BRI and RCEP, it is a member of BRICS and SCO but also QUAD and IPEF. The latter is Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity economic initiative launched in May 2022 by Biden to balance RCEP and not by chance including Japan, South Korea and Australia.[37] The presence of New Delhī in IPEF is part of the Act East Policy established in 2014 by Prime Minister Narendra Modi and aimed at increasing relations with ASEAN, just the same intentions described for Beijing’s strategy towards South-East Asia. This convergence worries Washington since if it is true that 7 out of the 10 ASEAN partners adhere to the IPEF, it is also true that New Delhī has already shown a distance from the first objective (“pillar”) of the initiative, which regards trade.[38] And in 2023, India will chair the SCO and G20 Summits.

In future, India will surely maintain its good historical relationship with Moscow. Since last October, Russia has become its chief oil supplier, overtaking Iraq and Saudi Arabia. Hardeep Singh Puri, Indian Minister of Petroleum and Natural Gas, both Housing and Urban Affairs, expresses himself as follows regarding potential moral conflicts for the war in Ukraine: “We have a 1.34 billion population, and we have to ensure that they are supplied with energy … We buy whatever is available.”[39]

Final remarks

Washington and Brussels choose sanctions, an act of war, as a channel to resolve international conflicts. Because sanctions are an act of war starving peoples and mainly building walls that prevent the free movement of people and goods. We speak of the essence of two values that had indicated us as the foundations of Western civilisation: peace and the free market. Not that these have not been repeatedly violated in the past or will not be in the future. We are not puritanical enough to believe it. Only how they are carried out nowadays leaves us speechless, not for ethical reasons (we are not puritans, I repeat), but because these mechanisms for executing international politics prove unproductive and are harmful to a correct geopolitical vision and diplomacy value. They push for war on an assumed ethical judgment that contradicts geopolitics as much as diplomacy. The solutions are identified on a punitive basis similar to the criminal laws of the nation states because the White House proposes itself as a referee, nay a court of last resort. An illegitimate and unrealistic practice in its claim, but it nevertheless worked in the past against weak and defenceless countries or even against individual unwelcome personalities. Something else is against countries that are weighty and sit on the UN Security Council.

The results are a world split into two parts, a new Cold War nobody misses and the reintroduction of protectionist systems limiting the free market environment. It is as if, in a now globalised reality, Washington and Brussels regard the world as reduced in its dimensions and international relations to Euro-Atlantic ones. Indeed, billions of people and millions of communities live outside that area, operate, trade, study, love, and pray outside the Western-style canons, even though up to now, they too have had to follow the behaviours (many righteous) and receive gadgets (many profitable or amusing) “recommended” by the West. To be ironic, I imagine in Russia you live badly without Coca-Cola, just as in the West do without original, non-smuggled caviar. In practice, the model proposed by Washington and Brussels is for everyone to consume their product. It just doesn’t work that way. The sanctioned countries export their energy products to the other half of the world as sanctioning bodies regulate their thermostats and pay more for the energy products imported from a few non-sanctioned countries.

The isolation of Russia, if this was the specific goal of the Euro-Atlantic sanctions, was and is illusory. Sure, the sanctioning devices hit Moscow’s finances immediately, but in the long run, they allow it to open up new markets that also mean political influence. New Delhī, while condemning the Russian invasion of Ukraine, has refused to adhere to the unfair sanctions enacted by many countries. At the same time, in India, oil imports from the Federation have increased by 23 times in 10 months.

Furthermore, more and more states join multilateral mechanisms involving now international relations. SCO and EAEU are institutions of Asian origin and conceived as a geopolitical strategy for Asia. The BRICS mark an attempt to claim a decision-making space for emerging countries where the Asian contribution is dominant and decisive. The BRI implements a mechanism of trade and development agreements free from constraints and ideological prejudices.

Could this attitude be the key to future international relations? Might. Provided that the principle of self-determination of peoples so dear to Woodrow Wilson is not only interpreted as a legal cornerstone for the definition of national state boundaries but also as the right of peoples to achieve an autonomous economic, social and cultural development, applying the concept of external self-determination. Specifically, the South for the South and not a residual subject of policies that are functional to the needs of the more advanced economies.

In this framework, the South of the world is ready to challenge Western paternalism precisely on the ground of its inspiring principles, not by facing up to them as in the past with useless Third Worldist theories, but by acknowledging those principles and at the same time demonstrating the ability to manage own peculiar development processes without imposing limiting subordination, especially in matters of finance and the economy.

The second condition is that on a geopolitical level, it should be acknowledged that extremist stances such as extreme isolationism or indiscriminate cosmopolitanism are not viable environments in an interconnected world. The value of multilateralism is just the confrontation between subjects who recognise each other to a compromise on interests that do not always converge. Indeed. The question “Indo-Pacific or Asia-Pacific?” asked in the text indicates the evolution of a duel for dominance over the Asian area. Nothing new. Only this time, the contenders are not all outside the area, unlike in the past when the British, French, Dutch and Americans divided up much of Asian territory. Despite centuries-old internal disputes, Asia seems to become a geopolitical player capable of internalising domestic conflicts and overcoming them because of common advantages.

Mainly Beijing has understood that the imperial strategy of divide and rule is less productive than that based on the reconciliation of disputes. Chinese diplomacy, through the SCO, invites Moscow and the EAEU to settle any disagreements on Central Asia and brings together India and Pakistan, Iran and Turkey, historically adversaries, around the same table. The multilateral aggregations born around the strongest countries represent this attempt. If Washington and Brussels approach them in a Cold War spirit as in the past, the future will lead to much more problematic conflicts than the one in Ukraine. The White House seemed to understand this after the failures in Afghanistan and Iraq. But the renewed strategy of expanding military alliances and unrest in the streets, which drive diplomacy peppered with steady regime-change auspices, will surely not help regain the influence lost in the Middle East and Central Asia, as well as in the Asia-Pacific area.

Even the Chinese economic and geopolitical dominance in Africa gained with neither wars nor bellicose attitudes would enter the same reasoning. But it’s another story.

REFERENCES

- Aneja, Atul (July 10th, 2015). BRICS, SCO, EAEU can define new world order: China, Russia. Retrieved from https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/BRICS-SCO-EAEU-can-define-new-world-order-China-Russia/article60334704.ece.

- Balci, Baris and Hacaoglu, Selcan (September 18th, 2022). Turkey Seeks to Be First NATO Member to Join China-Led SCO. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-09-17/turkey-seeks-china-led-bloc-membership-in-threat-to-nato-allies?srnd=fixed-income&leadSource=uverify%20wall.

- British Petroleum (2021). Statistical Review of World Energy | 70th Retrieved from https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/business-sites/en/global/corporate/pdfs/energy-economics/statistical-review/bp-stats-review-2021-full-report.pdf.

- Buck, Graham (June 23rd, 2022). BRICS countries keen to develop own payment systems – Industry roundup: 23 June. Retrieved from https://ctmfile.com/story/brics-countries-keen-to-develop-own-payment-systems-industry-roundup-twenty-third-june.

- Chu, Daye (September 20th, 2022). Talks emerge over a potential SCO FTZ, with NW.China’s Xinjiang as hub. Retrieved from https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202209/1275707.shtml.

- D’Agostino, Glauco (April 13th, 2022). West Progressive Isolation, Divisive Sanctions, and Asia under Sino-Russian Aegis. Retrieved from https://www.islamicworld.it/wp/west-progressive-isolation-divisive-sanctions-and-asia-under-sino-russian-aegis/

- D’Agostino, Glauco (July 2nd, 2022). From the BRICS, a free market lesson to the West. A matter of style! Retrieved from https://www.islamicworld.it/wp/from-the-brics-a-free-market-lesson-to-the-west/

- D’Agostino, Glauco (2022). Tehrān towards Beijing and Moscow: strategic alliances and overcoming divergences. Revistă de Geografie Politică, Geopolitică şi Geostrategie, 92-93(1). Bucureşti: Editura Top Form, Asociaţia de Geopolitica Ion Conea.

- Dragneva, Rilka (October 2018). The Eurasian Economic Union: Putin’s Geopolitical Project. Philadelphia, PA: Foreign Policy Research Institute. Retrieved from https://www.fpri.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/rpe-6-dragneva-final2.pdf.

- EIG-led Consortium including Silk Road Fund and Other Investors Complete Acquisition of 49% of Aramco Oil Pipelines Company (June 25th, 2021). Retrieved from http://www.silkroadfund.com.cn/enwap/27389/27391/42229/index.html.

- Ekman, Alice (July 22nd, 2019). China’s ‘New Type of Security Partnership’ in Asia and Beyond: A challenge to the Alliance System and the ‘Indo-pacific’ Strategy. Zurich, Switzerland: Center for Security Studies, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (ETH). Retrieved from https://isnblog.ethz.ch/uncategorized/chinas-new-type-of-security-partnership.

- Ekman, Alice (April 2022). China and the Battle of Coalitions. The ‘circle of friends’ versus the Indo-Pacific strategy. Chaillot Paper / 174. Paris: European Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS). Retrieved from https://www.iss.europa.eu/sites/default/files/EUISSFiles/CP_174_0.pdf.

- Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the United States of America (March 7th, 2022). State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi Meets the Press. Retrieved from http://us.china-embassy.gov.cn/eng/zgyw/202203/t20220308_10649559.htm.

- Giri, Chaitanya and Agarwal, Aashna (April 2nd, 2019). India & the influential SCO Energy Club. Retrieved from https://www.gatewayhouse.in/india-sco-energy/

- Gunia, Amy (November 17th, 2020). Why the U.S. Could Be the Big Loser in the Huge RCEP Trade Deal Between China and 14 Other Countries. Retrieved from https://time.com/5912325/rcep-china-trade-deal-us/

- Hashimova, Umida (July 20th, 2020). China Launches 5+1 Format Meetings With Central Asia. Retrieved from https://thediplomat.com/2020/07/china-launches-51-format-meetings-with-central-asia/

- Liptak, Kevin (May 23rd, 2022). Biden unveils his economic plan for countering China in Asia. Retrieved from https://edition.cnn.com/2022/05/22/politics/joe-biden-japan-monday/index.html.

- Lissovolik, Yaroslav (December 2018). Building with BRICS and BEAMS: a Constructivist Approach to Global Economic Architecture. Valdai Discussion Club. Retrieved from https://valdaiclub.com/files/21698/

- Lyons, Kate and Wickham, Dorothy (April 20th, 2022). The deal that shocked the world: inside the China-Solomons security pact. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/apr/20/the-deal-that-shocked-the-world-inside-the-china-solomons-security-pact.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China (May 20th, 2022). BRICS Joint Statement on “Strengthen BRICS Solidarity and Cooperation, Respond to New Features and Challenges in International Situation”. Retrieved from https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/202205/t20220520_10690224.html#:~:text=Theyper%20cent20reaffirmedper%20cent20theirper%20cent20commitmentper%20cent20to,basedper%20cent20onper%20cent20mutuallyper%20cent20beneficialper%20cent20cooperation.

- Nedopil, Christoph (July 2022). China Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Investment Report H1 2022. Shanghai: Green Finance & Development Center, FISF Fudan University. Retrieved from https://greenfdc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/GFDC-2022_China-Belt-and-Road-Initiative-BRI-Investment-Report-H1-2022.pdf.

- New Development Bank (December 29th, 2018). NDB’S Lending Commitment in 2018 Increased by 167%, Bringing Aggregate Approval Volume to USD 8 Billion. Retrieved from https://www.ndb.int/press_release/ndbs-lending-commitment-2018-increased-167-bringing-aggregate-approval-volume-usd-8-billion/

- New Development Bank (July 20th, 2022). New Development Bank (NDB) Approves USD 875 Million for Water, Sanitation, Ecotourism and Transport in Brazil, China and India. Retrieved from https://www.ndb.int/press_release/new-development-bank-ndb-approves-usd-875-million-for-water-sanitation-ecotourism-and-transport-in-brazil-china-and-india/

- Office of the President of Russia (February 4th, 2022). Joint Statement of the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China on the International Relations Entering a New Era and the Global Sustainable Development. Retrieved from http://en.kremlin.ru/supplement/5770.

- Pandey, Sanjay K. (September 2022). India, Central Asia and SCO: Prospect and Challenges, in Indian Council of World Affairs, “Renewing the Shanghai Spirit. India’s Presidency of Shanghai Cooperation Organization.” New Delhi: Sapru House. Retrieved from https://www.icwa.in/pdfs/ICWASCOGuestColumn.pdf.

- Press Trust of India (November 6th, 2022). Russia Becomes India’s Top Oil Supplier In October. Retrieved from https://www.outlookindia.com/business/russia-becomes-india-s-top-oil-supplier-in-october-news-235173.

- Rajagopalan, Rajeswari Pillai (May 7th, 2022). China’s Xi Proposes Global Security Initiative. Retrieved from https://thediplomat.com/2022/05/chinas-xi-proposes-global-security-initiative/

- Russia proposes partners in EAEU, BRICS, SCO increase settlements in national currencies (April 25th, 2022). Retrieved from https://interfax.com/newsroom/top-stories/78552/

- Sinha, Saurabh (September 10th, 2022). India stays out of Indo-Pacific trade pillar. Retrieved from https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/why-india-opted-out-of-joining-trade-pillar-of-ipef-for-now/articleshow/94106662.cms#:~:text=LOS%20ANGELES%3A%20India%20has%20chosen%20to%20opt%20out,the%20same%20to%20issues%20like%20environment%20and%20labour.

- Stronski, Paul and Sokolsky, Richard (January 2020). Multipolarity in Practice: Understanding Russia’s Engagement With Regional Institutions. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved from https://carnegieendowment.org/files/Stronski_Sokolsky_Multipolarity_final.pdf.

- Stuenkel, Oliver (2020). The BRICS and the Future of Global Order (Second Edition). Lanham, Boulder, New York, London: Lexington Books.

- Toosi, Nahal (November 4th, 2021). An ‘Illustrative Menu of Options’: Biden’s big democracy summit is a grab bag of vague ideas. Retrieved from https://www.politico.com/news/2021/11/04/biden-democracy-summit-technology-519530.

- Turkey’s Erdogan targets joining Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, media reports say (September 17th, 2022). Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/turkeys-erdogan-targets-joining-shanghai-cooperation-organisation-media-2022-09-17/

- United Nations (2022). Aggression against Ukraine : resolution / adopted by the General Assembly. Retrieved from https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3959039.

- Varma, D. Bala Venkatesh (September 2022). India and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization: Looking Forward to the 2023 Summit, in Indian Council of World Affairs, “Renewing the Shanghai Spirit. India’s Presidency of Shanghai Cooperation Organization.” New Delhi: Sapru House. Retrieved from https://www.icwa.in/pdfs/ICWASCOGuestColumn.pdf.

- Xinhua (July 24th, 2015). NDB president says to work with AIIB. Retrieved from http://www.china.org.cn/business/2015-07/24/content_36136846.htm.

- Xinhua (January 11th, 2017). Full text: China’s Policies on Asia-Pacific Security Cooperation. Retrieved from The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, http://english.www.gov.cn/archive/white_paper/2017/01/11/content_281475539078636.htm.

- Xinhua (April 21st, 2022). Keynote Speech by Xi Jinping at the Opening Ceremony of the Boao Forum for Asia Annual Conference 2022 (Full Text). Retrieved from http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-04/21/content_5686424.htm.

- Yang, Jiang (October 10th, 2022). China leading the race for influence in Central Asia. Copenhagen, Denmark: Danish Institute for International Studies. Retrieved from https://www.diis.dk/en/research/china-leading-the-race-influence-in-central-asia.

- Zongyuan, Zoe Liu (July 6th, 2022). The BRICS Show Resilience Amid Global Tumult. Retrieved from https://cpecwire.com/economy/brics-countries-pay-bank/

[1] Paul Stronski and Richard Sokolsky (January 2020). Multipolarity in Practice: Understanding Russia’s Engagement With Regional Institutions. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved from https://carnegieendowment.org/files/Stronski_Sokolsky_Multipolarity_final.pdf.

[2] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China (May 20th, 2022). BRICS Joint Statement on “Strengthen BRICS Solidarity and Cooperation, Respond to New Features and Challenges in International Situation”. Retrieved from https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/202205/t20220520_10690224.html#:~:text=Theyper%20cent20reaffirmedper%20cent20theirper%20cent20commitmentper%20cent20to,basedper%20cent20onper%20cent20mutuallyper%20cent20beneficialper%20cent20cooperation.

[3] Oliver Stuenkel (2020). The BRICS and the Future of Global Order (Second Edition), Ch. 6 Ufa, Goa, Xiamen, and Johannesburg: Towards a China-centric BRICS Grouping (2015-2019), p. 113. Lanham, Boulder, New York, London: Lexington Books.

[4] Atul Aneja (July 10th, 2015). BRICS, SCO, EAEU can define new world order: China, Russia. Retrieved from https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/BRICS-SCO-EAEU-can-define-new-world-order-China-Russia/article60334704.ece.

[5] In particular, “the SCO has established cooperative relations with major international organizations including the United Nations (UN), Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO), Conference on Interactions and Confidence Building Measures in Asia (CICA) and others.” D. Bala Venkatesh Varma (September 2022). India and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization: Looking Forward to the 2023 Summit, in Indian Council of World Affairs, “Renewing the Shanghai Spirit. India’s Presidency of Shanghai Cooperation Organization.” New Delhi: Sapru House. Retrieved from https://www.icwa.in/pdfs/ICWASCOGuestColumn.pdf.

[6] Rilka Dragneva (October 2018). The Eurasian Economic Union: Putin’s Geopolitical Project. Philadelphia, PA: Foreign Policy Research Institute. Retrieved from https://www.fpri.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/rpe-6-dragneva-final2.pdf.

[7] Russia proposes partners in EAEU, BRICS, SCO increase settlements in national currencies (April 25th, 2022). Retrieved from https://interfax.com/newsroom/top-stories/78552/

[8] Zongyuan Zoe Liu (July 6th, 2022). The BRICS Show Resilience Amid Global Tumult. Retrieved from https://cpecwire.com/economy/brics-countries-pay-bank/

[9] Graham Buck (June 23rd, 2022). BRICS countries keen to develop own payment systems – Industry roundup: 23 June. Retrieved from https://ctmfile.com/story/brics-countries-keen-to-develop-own-payment-systems-industry-roundup-twenty-third-june.

[10] Turkey’s Erdogan targets joining Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, media reports say (September 17th, 2022). Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/turkeys-erdogan-targets-joining-shanghai-cooperation-organisation-media-2022-09-17/

[11] Baris Balci and Selcan Hacaoglu (September 18th, 2022). Turkey Seeks to Be First NATO Member to Join China-Led SCO. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-09-17/turkey-seeks-china-led-bloc-membership-in-threat-to-nato-allies?srnd=fixed-income&leadSource=uverify%20wall.

[12] Xinhua (July 24th, 2015). NDB president says to work with AIIB. Retrieved from http://www.china.org.cn/business/2015-07/24/content_36136846.htm.

[13] New Development Bank (December 29th, 2018). NDB’S Lending Commitment in 2018 Increased by 167%, Bringing Aggregate Approval Volume to USD 8 Billion. Retrieved from https://www.ndb.int/press_release/ndbs-lending-commitment-2018-increased-167-bringing-aggregate-approval-volume-usd-8-billion/; New Development Bank (July 20th, 2022). New Development Bank (NDB) Approves USD 875 Million for Water, Sanitation, Ecotourism and Transport in Brazil, China and India. Retrieved from https://www.ndb.int/press_release/new-development-bank-ndb-approves-usd-875-million-for-water-sanitation-ecotourism-and-transport-in-brazil-china-and-india/

[14] Yaroslav Lissovolik (December 2018). Building with BRICS and BEAMS: a Constructivist Approach to Global Economic Architecture. Valdai Discussion Club. Retrieved from https://valdaiclub.com/files/21698/

[15] Alice Ekman (April 2022). China and the Battle of Coalitions. The ‘circle of friends’ versus the Indo-Pacific strategy. Chaillot Paper / 174. Paris: European Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS). Retrieved from https://www.iss.europa.eu/sites/default/files/EUISSFiles/CP_174_0.pdf.

[16] Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the United States of America (March 7th, 2022). State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi Meets the Press. Retrieved from http://us.china-embassy.gov.cn/eng/zgyw/202203/t20220308_10649559.htm.

[17] Glauco D’Agostino (July 2nd, 2022). From the BRICS, a free market lesson to the West. A matter of style! Retrieved from https://www.islamicworld.it/wp/from-the-brics-a-free-market-lesson-to-the-west/

[18] Office of the President of Russia (February 4th, 2022). Joint Statement of the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China on the International Relations Entering a New Era and the Global Sustainable Development. Retrieved from http://en.kremlin.ru/supplement/5770.

[19] Glauco D’Agostino (April 13th, 2022). West Progressive Isolation, Divisive Sanctions, and Asia under Sino-Russian Aegis. Retrieved from https://www.islamicworld.it/wp/west-progressive-isolation-divisive-sanctions-and-asia-under-sino-russian-aegis/

[20] United Nations (2022). Aggression against Ukraine : resolution / adopted by the General Assembly. Retrieved from https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3959039.

[21] Alice Ekman (July 22nd, 2019). China’s ‘New Type of Security Partnership’ in Asia and Beyond: A challenge to the Alliance System and the ‘Indo-pacific’ Strategy. Zurich, Switzerland: Center for Security Studies, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (ETH). Retrieved from https://isnblog.ethz.ch/uncategorized/chinas-new-type-of-security-partnership.

[22] Xinhua (January 11th, 2017). Full text: China’s Policies on Asia-Pacific Security Cooperation. Retrieved from The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, http://english.www.gov.cn/archive/white_paper/2017/01/11/content_281475539078636.htm.

[23] Christoph Nedopil (July 2022). China Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Investment Report H1 2022. Shanghai: Green Finance & Development Center, FISF Fudan University. Retrieved from https://greenfdc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/GFDC-2022_China-Belt-and-Road-Initiative-BRI-Investment-Report-H1-2022.pdf.

[24] EIG-led Consortium including Silk Road Fund and Other Investors Complete Acquisition of 49% of Aramco Oil Pipelines Company (June 25th, 2021). Retrieved from http://www.silkroadfund.com.cn/enwap/27389/27391/42229/index.html.

[25] Sanjay K. Pandey (September 2022). India, Central Asia and SCO: Prospect and Challenges, in Indian Council of World Affairs, cit.

[26] Chaitanya Giri and Aashna Agarwal (April 2nd, 2019). India & the influential SCO Energy Club. Retrieved from https://www.gatewayhouse.in/india-sco-energy/

[27] Yang Jiang (October 10th, 2022). China leading the race for influence in Central Asia. Copenhagen, Denmark: Danish Institute for International Studies. Retrieved from https://www.diis.dk/en/research/china-leading-the-race-influence-in-central-asia.

[28] Umida Hashimova (July 20th, 2020). China Launches 5+1 Format Meetings With Central Asia. Retrieved from https://thediplomat.com/2020/07/china-launches-51-format-meetings-with-central-asia/

[29] Chu Daye (September 20th, 2022). Talks emerge over a potential SCO FTZ, with NW.China’s Xinjiang as hub. Retrieved from https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202209/1275707.shtml.

[30] China is the biggest energy-consuming country in the World, followed by United States, India, and Russia (Data 2020). British Petroleum (2021). Statistical Review of World Energy | 70th edition. Retrieved from https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/business-sites/en/global/corporate/pdfs/energy-economics/statistical-review/bp-stats-review-2021-full-report.pdf.

[31] Glauco D’Agostino (2022). Tehrān towards Beijing and Moscow: strategic alliances and overcoming divergences. Geopolitica. Revistă de Geografie Politică, Geopolitică şi Geostrategie, 92-93(1). Bucureşti: Editura Top Form, Asociaţia de Geopolitica Ion Conea.

[32] Nahal Toosi (November 4th, 2021). An ‘Illustrative Menu of Options’: Biden’s big democracy summit is a grab bag of vague ideas. Retrieved from https://www.politico.com/news/2021/11/04/biden-democracy-summit-technology-519530.

[33] Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan (May 7th, 2022). China’s Xi Proposes Global Security Initiative. Retrieved from https://thediplomat.com/2022/05/chinas-xi-proposes-global-security-initiative/

[34] Xinhua (April 21st, 2022). Keynote Speech by Xi Jinping at the Opening Ceremony of the Boao Forum for Asia Annual Conference 2022 (Full Text). Retrieved from http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-04/21/content_5686424.htm.

[35] Kate Lyons and Dorothy Wickham (April 20th, 2022). The deal that shocked the world: inside the China-Solomons security pact. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/apr/20/the-deal-that-shocked-the-world-inside-the-china-solomons-security-pact.

[36] Amy Gunia (November 17th, 2020). Why the U.S. Could Be the Big Loser in the Huge RCEP Trade Deal Between China and 14 Other Countries. Retrieved from https://time.com/5912325/rcep-china-trade-deal-us/

[37] Kevin Liptak (May 23rd, 2022). Biden unveils his economic plan for countering China in Asia. Retrieved from https://edition.cnn.com/2022/05/22/politics/joe-biden-japan-monday/index.html.

[38] Saurabh Sinha (September 10th, 2022). India stays out of Indo-Pacific trade pillar. Retrieved from https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/why-india-opted-out-of-joining-trade-pillar-of-ipef-for-now/articleshow/94106662.cms#:~:text=LOS%20ANGELES%3A%20India%20has%20chosen%20to%20opt%20out,the%20same%20to%20issues%20like%20environment%20and%20labour.

[39] Press Trust of India (November 6th, 2022). Russia Becomes India’s Top Oil Supplier In October. Retrieved from https://www.outlookindia.com/business/russia-becomes-india-s-top-oil-supplier-in-october-news-235173.