by Glauco D’Agostino

This article was first published in “Geopolitica. Revistă de Geografie Politică, Geopolitică şi Geostrategie“, Anul XXI, nr. 99 (2/2023) “PRESIUNI GEOPOLITICE II“, Editura “Top Form”, Asociaţia de Geopolitica Ion Conea, Bucureşti, 2023.

Fig. 1 – Romania: Vatra Moldoviței (Moldavia), Moldovița Orthodox Monastery, Annunciation Church (by the author)

Abstract

Eastern Europe, from the Baltic to the Black Sea, from the Balkans to the Caspian, exhibits an area of strategic interest for the powers vying for world leadership and a crucial bridge to Asia. Officially, the European Union speaks of Western values, democracy and cooperation. Its very model of integration is based on values. In Eastern Europe, the perception is that a feeling of competition with its new partners rather than cooperation and integration has prevailed in Brussels. A semantic misunderstanding due to historical, cultural and sensitivity differences. This impacts the interpretation of the historical function of Europe and Christianity as its foundation, on the conception of the State and the definition of consequent rights. The West, in general, feels obliged to spread even to the East an Enlightenment-inspired individualist vision of rights that conflicts with the organic-traditional values advocated by many Eastern European realities. Secularism theorises the separation between State and Church as an assumption of democratic institutions and the rejection of religion in the private sphere. But religious institutions have had a leading role in the nation-building process in the East that, in post-Soviet times, allowed them to be considered the only source of legitimate power to reconstitute state authorities.

Another controversial issue concerns national identity and multiculturalism. Brussels does not appreciate the attitude of some European leaders, but this raises the question of individual nation-states’ prerogatives in terms of rights and cultural choices. The model of values to be exported is worth little if those values are interpreted differently in the East. The impression is that the new E.U., the one enlarged to many countries of the former Soviet orbit, discloses an attitude of “Western-style liberal imperialism” but with expansionist overtones. The westernisation of those lands leads towards the homologation of a single thought, in the same way as the Marxist-Leninist assumptions, albeit with different methods and proposals. Anyway, non-negotiable assumptions! East pockets not only liberalism and unlimited individual freedoms but utilitarianism, consumerism, precariousness and inequality.

Keywords: Europe, Eastern Europe, European Union, integration, cooperation, absorption, values, democracy, rights, Christianity, religion, secularism, national identity, multiculturalism.

***

Introduction

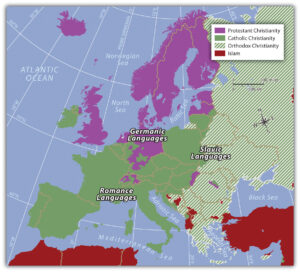

“Europe ends where Western Christianity ends and Islam and Orthodoxy begin.”[1] This is how Samuel Huntington, theorist of waves of democracy and author of The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order, conceived Europe. When he passed away in 2008, the Harvard professor of democratic faith had instead had time to see Orthodox Romania and Bulgaria enter the European Union as member countries. Sure, it is not the event that makes Romanians and other Eastern European peoples European. But an attempt to oppose each other in religious key communities of different sensitivities (as we will see) and nevertheless rooted in common origins displays the lack of caution in confusing the cultural expressions of peoples with the geopolitical conveniences of state establishments.

What was not apparent to the American Huntington in the 1990s was well understood by the Slavic Pope John Paul II in the 1980s when speaking of “unity which is neither absorption nor fusion” in his Encyclical Slavorum Apostoli.[2] So clash versus unity. The question is whether geopolitics can replace religion and culture in interpreting peoples’ lives; if anything, it affects them in the short term. Different languages and different geopolitical eras. In the middle, the fall of the Berlin Wall. And yet, the Western Christianity Slavic Pope, in 1995, citing the Millennium of the Baptism of Kievan Rus’, said related to the concepts of East and West: “The Church must breathe with her two lungs!”[3]

Fig. 5 – Dominant Language Groups and Christian Denominations in Europe (Source: Saylor Academy, 2012)

Europe up to the Urals – another variant of John Paul II’s idea – can be read today in the regional groupings of UN member states. Eastern European states encompass all lands east of Germany, including the Russian Federation, Baltic countries, and all Balkan and Transcaucasian countries.[4] It should be noted that in this cluster of 23 countries overall with a Slavic and Christian majority, as many as 10 of them belong to other ethnic groups (Baltic, Finno-Ugric, Romance-speaking, Caucasian, Turkic, Armenian and Albanian) and 3 (Albania, Azerbaijan and Bosnia and Herzegovina) have a Muslim majority. An area that is certainly not homogeneous to be able to identify its features and behaviours.

The geopolitics factor

Many researchers distinguish between Central and Eastern Europe, but Orthodox Greece is never included among Eastern European countries. Let us leave aside the case of Orthodox Cyprus, which, as an Asian country, is an integral part of the European Union. The evidence is that the criterion adopted is geopolitical. Consequently, all countries once considered to be in the Soviet influence area are Eastern. This argument leads to discrimination, perhaps not even intentional, which causes those nations to be like pariahs of Europe, also now that many are E.U. and NATO members. In 2014, the Polish writer Agata Pyzik, author of Poor but Sexy: Culture Clashes in Europe East and West, interpreted this widespread sentiment in the East: “This rush to the west is a fallout from the ancient divisions of the continent, which have led to the association of everything ‘west’ with civilisation and culture, and everything ‘east’ with barbarism.”[5]

Therefore, geopolitics enters the respect of nations as one of the elements of pressure, perhaps the most conditioning one, on national and international policy choices. Eastern Europe, from the Baltic to the Black Sea, from the Balkans to the Caspian, exhibits an area of strategic interest for the powers vying for world leadership and a crucial bridge to Asia. Nor European-style multilateralism attenuates the stringent claims to economic and social expansion and cultural absorption. In this context, the progressive eastward enlargement of the E.U. and NATO, while not contested diplomatically by the other contenders, did not consider the limits of these operations and the safety margins of neighbouring countries.[6]

Fig. 10 – Hungary: Budapest, Pest, Catholic Basilica of the Roman rite of St. Stephen I of Hungary (by the author)

The entry of Slovenia, the Western Slavic and the Baltic and Finno-Ugric countries into the E.U. in 2004 is understandable and appropriate. The opening to the countries bordering the western Black Sea is already problematic on geopolitical grounds, with the entry in 2007 of Romania and Bulgaria, the first countries with an Orthodox majority. In 2013, Croatia’s accession allowed Brussels a path to the other countries of the former Yugoslavia. NATO seems to be the spearhead, with the entry in 1999 of three countries of the Visegrád Group (Poland, Czech Republic and Hungary) into membership, followed in 2004 by the Baltic Countries, Slovakia (the fourth of the Visegrád Group), Slovenia, Romania, and Bulgaria. On the Balkan route, Croatia and Albania joined the Atlantic Alliance in 2009, as did Montenegro and North Macedonia in 2017 and 2020. Excluding NATO installations, Eastern Europe is already crowded with U.S. military bases: among those operated by the Army, Navy and Air Force, 7 are located on the western Black Sea coast, 5 on the Baltic shores, and 2 in Kosovo. It reveals the guidelines and priorities of the White House’s geo-strategic action in the area.

Demonstrating resilience, Putin has watched for ten years without blinking the political and military pushes coming from the West. The balance shattered in 2008 when the NATO Summit in Bucharest, despite the Kremlin’s state of perplexity, declared its acceptance of Ukraine and Georgia’s candidacies. The Russian Federation reacts immediately, recognising the Georgian secessionist states of Abkhazija and South Ossetia. Then the events in Ukraine, with the Maidan Revolution in 2014, which Moscow interpreted as a coup d’état, and the consequent reaction with the annexation of Crimea, followed by the counter-reaction of Kyiv against the Donbass, by the failed Minsk Agreements, up to the current fratricidal war which is bloodying traditionally neighbouring peoples. We will not retrace the too well-known events because the intent is always to underline the pressures that Eastern Europe is undergoing on various fronts.

The value factor

Officially, the European Union speaks of Western values, democracy and cooperation. Its very model of integration is based on values. In Eastern Europe, the perception is that a feeling of competition with its new partners rather than cooperation and integration has prevailed in Brussels.[7]

Fig. 12 – Belarus: Baránavichy (Brest), Orthodox Church of the Holy Myrrh-Bearers (Source: https://megaconstrucciones.net/)

The Association Agreements with Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia, the result of the Eastern Partnership (EaP) initiative, appear more as the implementation of geopolitical interests on the Black Sea route than functional tools for the rise of local development in a civic and economic sense. The same goes for other now uncomfortable neighbours outside the Union, such as Belarus, which was induced to be suspended from the Eastern Partnership in 2021, perhaps because it has been a founding member of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) since 2015 and could act as a link between Europe, with which it borders across three frontiers, and Trans-Uralic Asia. In the case of Russia, after the suspension in 2014 of its participation in the G8, by the following year, it was no longer a strategic partner with the E.U. In 2016, the Belarus-born Alena Karastseleva, Director of the Institute for Global Sustainable Development at the University of Warwick, England, noted “what is now seen as the open and ‘exclusive’ competition between the E.U. and Russia in the eastern region, which stabilisation is claimed to be only possible through their further expansion into the contested territories, once on the ‘path of war’.”[8]

Perhaps, there is a short circuit that concerns integration and values. A semantic misunderstanding due to historical, cultural and sensitivity differences. This impacts the interpretation of the historical function of Europe and Christianity as its foundation, on the conception of the State and the definition of consequent rights.

The Copenhagen criteria for acquiring E.U. membership guarantees “democracy, the rule of law, human rights and respect for and protection of minorities, the existence of a functioning market economy.”[9] The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union refers to “universal values,” “democracy,” and “rules of law.”[10] About the rights deriving from it, the Charter cites the 1950 Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms and subsequent protocols. We assume that the 13 continental states that have become E.U. members after the solemn proclamations of the criteria and the fundamental rights, respectively, in 1993 and 2000, share the assumptions. There is no need to address juridical questions on how these rights are applied or on possible violations, but rather to underline substantial differences of cultural views between some secularised state institutions and religious ones concerning the issue.

The religion factor

As for religions, Orthodox and Catholics are the majority of the population in this area. Despite a significant decline in Christian affiliation and religious commitment throughout Western Europe and the substantial stability in Central and Eastern Europe in an out-and-out revival of religion after the USSR collapse,[11] the West, in general, feels obliged to spread even to the East an Enlightenment-inspired individualist vision of rights that conflicts with the organic-traditional values advocated by many Eastern European realities.[12] For this reason, if and when one intends to allude to abortion, same-sex marriages, surrogacy and euthanasia as human rights, this conflicts with the conscience of most citizens of the East, whether or not they are faithful to a religious belief.[13]

This is how the Holy and Great Synod of the Orthodox Church of 2016 expressed itself on the subject:[14]

Contemporary society approaches marriage in a secular way with purely sociological and realistic criteria, regarding it as a simple form of relationship – one among many others – all of which are entitled to equal institutional validity … The approach to human rights on the part of the Orthodox Church centers on the danger of individual rights falling into individualism and a culture of ‘rights’. A perversion of this kind functions at the expense of the social content of freedom and leads to the arbitrary transformation of rights into claims for happiness, as well as the elevation of the precarious identification of freedom with individual license into a “universal value” that undermines the foundations of social values, of the family, of religion, of the nation and threatens fundamental moral values.

Fig. 14 – Russia: Moscow, Patriarch Kirill celebrates the Liturgy of St. Basil the Great at the Cathedral Church of Christ the Saviour (Source: https://basilica.ro/)

Distinguishing between traditsija (a tradition in the sense of custom) and Predanie (Tradition as transmission), Kirill, Patriarch of Moscow and all Rus’, wrote when he was still the Metropolitan of Smolensk and Kaliningrad:[15]

We understand any deviation from the Predanie as a violation of the norm of faith, or heresy … Following this norm non only does not constrain man’s freedom but protects him, as mother’s bosom from death.

Not lacking, however, openings of different addresses, the Russian Orthodox Church states:

Human rights cannot be superior to the values of the spiritual world … should not come into inflict with the Divine Revelation … For many people in various parts of the world it is not so much secularized standards of human rights as the creed and traditions that have the ultimate authority in their social life and inter-personal relations.[16]

Fig. 16 – Russia: Moscow, the new Mosque Jum’ah (of Friday Prayer) (Source: http://rusarab.ru/media/)

On the Islamic front, in 2014, Tatar Rawil İsməğil uğlı Ğəynetdinev, at the time Grand Muftī of the Moscow-based Spiritual Board of Muslims of the European Region of Russia, said:[17]

Beginning with the Renaissance, Europeans have rejected faith in the Creator, because it was burdensome to them. The pursuit of wealth for personal gain eclipsed everything else, individual desires were placed above common interests, and an anthropocentric type of thinking dominated. These were called universal values, and then these values were spread across the entire world, including by colonialist methods.

This difference in approach to values opens up the issue of relations between the state and religious institutions, one of the more controversial, mainly because of the ideological attitude the West brings with it as a legacy of political liberalism, which the East has never known. The extremity of this concept, secularism, theorises the separation between State and Church as an assumption of democratic institutions and the rejection of religion in the private sphere. As stated in 2002 by the Romanian Mihai Baciu as rapporteur before the Committee on Culture, Science and Education of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, religion and politics “can never be totally separated … [Religion] cannot stand aloof from the public sphere.”[18] In their work of expansion to the East, Brussels and Washington have failed to consider “the principle of symphonia (complementarity) of the political and religious leadership … [which] has always been at the crux of Orthodoxy’s enculturation and adaptation to circumstances.”[19] Complementarity involves recognition and acceptance of each other’s roles of authority (ethical and spiritual on the part of the Church and sovereignty on the part of the State), but also mutuality of support in attitude.

Religious institutions have had a leading role in the nation-building process in the East, which was renewed in the institutional de-Sovietisation of the new countries after 1989 and which, in some situations, allowed them to be considered the only source of legitimate power to reconstitute state authorities.[20] Think of the boost the Catholic Church has given to the post-communist political reconstruction of Poland and the function the Orthodox Church has held for national values and identities in all the Orthodox-majority European countries freed from Soviet influence.

We then understand the apprehension of these Churches for the “free market in beliefs” brought about by religious missionaries from outside (Baciu, 2002) and the penetration of new religious movements as neo-protestant born-again evangelical groups (such as Baptists, Pentecostals, Adventists and the Brethren Assemblies),[21] Neopagan, Neoshamanic, and New Age movements.[22] As for the first group, the formation of specific Roma Pentecostal Churches in Romania and Bulgaria after 1991 is documented for the respective countries by Sorin Gog (cit.), from the Babeș-Bolyai University in Cluj-Napoca, Milena Benovska-Sabkova, from the South-West University of Blagoevgrad, and Velislav Altanov, from the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences.[23] In the case of the New Ages, Gog claims that their “alternative spiritualities” have even penetrated the fields of psychology, management, healthcare, welfare and business and conquered “economists, lawyers, teachers, creative workers, service specialists, IT-personnel, engineers, experts, consultants,” that is the beating heart of the States.[24]

Fig. 17 – Armenia: Tsakhkadzor (Kotayk), Armenian Apostolic Ketcharis Monastery, Church of the Surp Nshan (Holy Sign of Cross) (by the author)

However, the States’ attitude towards religious institutions is complex and varied in the East. In general, direct state funding of Churches does not exist; only some Orthodox-majority countries refer to the prevailing Church or recognise its special status by law; those with a Catholic majority signed concordats with the Holy See or have “recognised churches;” Armenia and Moldova ban proselytism on their territory; in Estonia, where the majority of people declares they are not affiliated with any religion, while the remainder is Christian in any case, Churches based in other countries may not own real estate (Baciu, 2002).

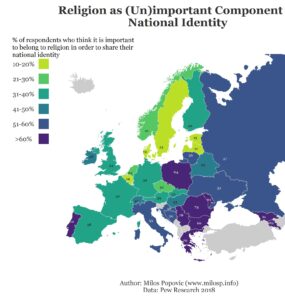

The identity factor

In Western European countries, religious, ethnic or linguistic recognition as a factor of national belonging, regarded as a feature of Orthodox-majority countries, is not decisive (Pew Research Center, 2018). But precisely the national identities issue is nonetheless present even outside the area of Orthodoxy diffusion, given that some modernist squads often criticise the Visegrád Group, made up of Central European countries, for its trait of “identity, patriotism, collective memory and the protection of territory and values.”[25] Brussels, as well, has raised doubts about the lack of solidarity of these countries towards the formulation of European policy during the 2015 migration crisis[26] and on their legislation about multiculturalism, national identity, judicial system and even the rule of law.

The principle of legality is one of the Europe cornerstones conveyed in the Charter of Fundamental Rights, authorising some analysts to object to the democratic nature of these countries, primarily Poland and Hungary.[27] In particular, Brussels does not appreciate the attitude of the Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and some of his accents of 2018 raise concern: “Central Europe … has a special culture. It is different from Western Europe.” Even more explicit when he stated “the right to defend [its] Christian culture, and the right to reject the ideology of multiculturalism” (Pew Research Center, 2018). However, Budapest does not like the attitude of Brussels when it limits individual nation-states’ prerogatives in terms of rights and cultural choices. It sees it as a top-down approach, not allowing participation in building a mutual path. This brings us back to the reflections of Julian Pänke, from the Department of Political Science and International Studies (POLSIS) of the University of Birmingham, UK, on the European Union “as a liberal empire based on strategies of geopolitical modelling of hierarchy in centre-periphery relations and normative discourses to legitimise that hierarchical order.”[28]

It is yet another semantic short circuit with purely political implications if it is true the E.U. has based since 2020 precisely on the postulates of democracy and legality that conditionality mechanism subordinating access to European funding to compliance with those assumptions.[29] It is indeed a foreign policy conditioning over the 4 of Visegrád, struck down as Euro-sceptics and considered ambivalent regarding relations with Moscow, a sort of “mini Trojan horses.”[30] In other words, further pressure bordering on blackmail, exerted by a community body increasingly moving towards delegitimising its credibility. In practice, the line has passed among the Brussels bureaucrats that it is enough to have relations with the Kremlin to be necessarily suspected of illiberality and anti-democratic. Furthermore, the standardisation of this suspicion could, in turn, appear somewhat illiberal and anti-democratic.

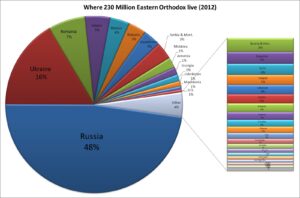

The history factor

Russia and Ukraine host a large part of the Orthodox population in this area of the European sub-continent.[31] The ethnic and religious Russian minority in Ukraine is a significant problem for the acclaimed homogeneity of Ukrainians as a nation. Here we limit the analysis to ascertaining the complexity of a land that is fascinating for its versatility but rich in cultural influences playing a decisive part in its history. In terms of religious presence, a particular historical (but also geopolitical) value throughout Eastern Europe has been acquired by the local Eastern Catholic Churches, “particular” churches sui iuris of the Byzantine rite but in full communion with the Pope in Rome, each competent for almost all Slavic countries, Romania, Armenia, and Albania. Ukraine also has its Greek Catholic Church, second only to the Latin Church in terms of believers number, whose recognition by Rome dates back to the Union of Brest of 1595, established by Orthodox hierarchies of Ruthenia (roughly the current Ukraine and Belarus) at odds to the elevation of Moscow to Patriarchate.

That event, sanctioned on the soil of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, makes us understand how the coldness between Ukrainians and Russians has deep historical roots, but also why the link between Poles and Lithuanians and their feeling of aversion towards Moscow persists nowadays, following the Commonwealth tripartition by the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia, and the Habsburg monarchy of 1795 until independence in 1918. And yet, the cultural imprint of that tripartition is still alive and detectable in Vilnius (which became Russian), in Lviv and Cracow (Habsburg), and in Poznań and Gdańsk (Prussian).

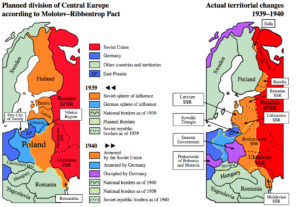

Perhaps the nationalism characteristic of Eastern Europe is a little shocking, but the borders of some nations are determined by wars and not by liberation movements. After WWI, Russian Vil’no first became Lithuanian Vilnius and then Polish Wilno; Habsburg Lemberg and Krakau became Polish Lwów and Kraków; and Prussian Posen and Danzig became Poznań and Gdańsk. After WWII, the Soviet Union again acquired Vil’no and Lvov on behalf of Lithuania and Ukraine, but also the German Immanuel Kant’s Königsberg, which has since been called Kaliningrad and today has the strategic importance to be a Russian navy base in the Baltic, although separated from the rest of the Russian Federation by Lithuanian and Belarusian territories. Of course, they are examples of widespread situations in Eastern Europe and determined by the subversion of Empires that had given stability to the continent and beyond. They are also outcomes of those Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact secret protocols, which, in addition to the situations described for Lithuania and Ukraine, ended up delivering Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina to the Soviet orbit, determining new borders to the advantage of Moldova and Ukraine and to the detriment of Romania, which in turn was the result of the Union with Transylvania of Alba Iulia, formerly Habsburg.[32]

This historical review, which has the Vilnius-Lviv-Bessarabia geographical axis as its focal point, serves to witness that the region between the Baltic and the Black Seas cannot be considered a new barrier dividing Huntington-style civilisations, nor a sort of Iron Curtain advanced for geopolitical reasons, as much as the crossroads of historical cultures layered over the centuries and rejecting rigid ideological barriers. Here, cultures formed over the centuries intersect in a difficult coexistence made up of national pride and suspicions, settled on newly formed state structures conceiving ethnic groups and languages based on contingent political borders and not vice versa. These barriers are often caused by geopolitical pressures leading to oppositions and misunderstandings functional to specific interests. The easy game of divide et impera is always in play in Europe.

Fig. 27 – Ukraine: Metropolitan Epiphany, Primate of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine (Source: Brewminate)

Churches are by no means immune from this context. Today in Ukraine, apart from the historically formed Greek Catholic Church, Orthodoxy is represented by the Orthodox Church of Ukraine and the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate), which rightly mirrors the current geopolitical situation but calls, as well, for reflections on the autocephaly institution in the Orthodox Church. There were three Churches in Ukraine until 2019, when, in the presence of war in Donbass, the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople recognised the autocephaly of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine, a merger of the self-proclaimed Kyiv Patriarchate (deemed schismatic by the Moscow Patriarchate competent for jurisdiction) and another autocephalous branch born in 1917 after the Russian Empire dissolution. In addition to Constantinople, only the Patriarchate of Alexandria and the Churches of Cyprus and Greece have recognised that of Ukraine, while many other autocephalous Churches have not formalised recognition.

Fig. 29 – Bulgaria: Sofia, Orthodox Cathedral of Aleksandr Nevskij (Source: Project Hop, History of the Orthodox People)

To better understand the matter, we need to go back to 2016, when the Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew gathered in Crete the already mentioned Holy and Great Synod, summoning the representatives of the other three historical Patriarchates of Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem and of the other ten Patriarchates and recognised autocephalous Churches. A few days earlier, the Ukrainian Rada “voted in a resolution asking the Ecumenical Patriarchate to approve an independent national church on its territory, outside Moscow’s jurisdiction,”[33] confirming the political significance the Synod assumed. The result of this interference, perceived as pressure by many ecclesiastics, was the non-attendance of the delegations of the Patriarchates of Antioch, Moscow, Bulgaria and Georgia. Thus, the recognition of the Synod also fell, as it was not ecumenical and to be considered only an ordinary Council.

The relationship between the Patriarchate of Moscow and the Ecumenical one had already begun to deteriorate over the past twenty years due to the recognition by Constantinople of the autonomy of the Estonian Apostolic Orthodox Church since placed under the Phanar direct jurisdiction. The topic became particularly sensitive, considering the Estonian origins of then-Patriarch Aleksij, born in Tallinn. And since the misunderstandings have had a crescendo and continue nowadays, given the restoration of the Latvian Orthodox Church by the Latvian Parliament in 2022.

Several similar episodes to Ukraine and Latvia cases had occurred in the past. From the historical point of view and as far as we are concerned, autocephaly, precisely for the jurisdictions usually coinciding with national borders, has led in recent centuries to the conditioning by the Nation-States arising from the Empires’ disintegration. For instance, in Greece, Serbian Vojvodina, United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, and Bulgaria, autocephalies have been demanded (or granted, as in the Bulgarian case) within the framework of independence against the Ottomans, even though others have been requested by the local clergy, as in Georgia in 1917 and Albania in 1922. Constantinople recognised all those Churches, but in general, recognition remains a problem because the limits of the authority of the primus inter pares in the matter of jurisdiction are still controversial, and the non-recognition is often interpreted as hostility towards national independence.

Among the thorniest problems is the dispute between the two autonomous Metropolises of Chișinău and All Moldova, under the Moscow Patriarchate jurisdiction, and that of Bessarabia, reactivated in 1992 under the Romanian Patriarchate, which re-proposes the historic Russian-Romanian conflict over those lands, given that the Moldovan government considers the Metropolis of Bessarabia a “breakaway movement” (Baciu, 2002).

Final remarks

China looks at Europe as the Western offshoot of the Euro-Asian continent; the United States regards it as the eastern part of the Western world; Russia as the beneficiary of its energy policy (did it at least until the sanctions); the European Union as a land for the expansion of democratic liberalism; Eastern European countries as the Christianity source; each of the European countries as the instrument of its own material or spiritual well-being, according to their sensitivities. All these perceptions share the ideologic vision of a profane messianism which translates into the idea of domination. The little respect for peoples’ history and customs led to the standardisation of principles and behaviours as yesterday’s winners imposed (and today’s emulators go on) their own economic, political, social and cultural hegemony.

In the case of Eastern European countries, their history was not born with the USSR’s fall and not even with the nightmare of the communist occupation of their institutions and lives. I would add not even with the assignment of a State to each Nation, as the latter meaning is ethnic and not necessarily corresponding to an institutional command structure. We can deem the division of Europe into 55 States (including the de facto ones, such as Kosovo, Northern Cyprus, Transdnestrija, South Ossetia and Abkhazija) as a conquest of democracy and independence, yet, we must compare it, in regards to the stability of the Continent, with the 32 existing before WWII and the 23 before WWI. As if to say, wars lead to the multiplication of players active in the geopolitical game, following the strategy of divide and rule functional to some of the subjects outside the area.

The subdivision of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia also responded to non-religious and not even ideological sakes (given the permanence in the power of the communist Slobodan Milošević), but to weaken the Balkan resistance to geopolitical pressure from the West. The fierce war in Yugoslavia passed off as an internal war between religions, brought the conflict back to Europe and served to shatter the ethnic unity of the South Slavs with the formation of 7 new state entities. And the people of Czechoslovakia (again a Slavic subject in question) suffered the same fate, albeit with different methods after the so-called 1989 Velvet Revolution. Once again, the Balkan strategy was implemented, the same the Congress of Berlin had conceived in 1884-85 to corner the Ottoman and Russian Empires. Hence, nationalism has deep roots and has nothing to do with totalitarianism and despotism. It is the reaction, the historical nemesis, the flip side of liberal and Enlightenment rhetoric. Often one has to dig deep to identify the aggressors and the victims, the instigators and the useful idiots in their employ.

More concretely, this essay identifies some problems inherent in the relationship between Eastern and Western Europe to stimulate a debate on whether (sic stantibus rebus or in fieri) a more cooperative nexus or a predominance aimed at cold casting prevails. The impression is that the new European Union, the one enlarged to many countries of the former Soviet orbit (and which makes no secret of co-opting them all), discloses an attitude of “Western-style liberal imperialism” but with expansionist overtones borrowed from Napoleonic Paris. On the other hand, the model of values to be exported is worth little if those values are interpreted differently in the East. The paradox is that Eastern citizens have gone from the political and cultural imposition of Communism to conditioning (which is not an imposition) about sharing those values as a prerequisite for being considered liberal and democratic. From one ideology to another without being able to utter a word, even if many accept this new condition because the West brings economic prosperity and development rather than values!

Sure, in the West, people have not proven the tragedy of Communism, with its profoundly materialistic character aimed at tearing down fundamental social structures such as the family and total control of public and private life.[34] They have had no experience of the repression virulence and anti-religious propaganda, while the streets of Rome and Paris were awash with red flags. But Eastern Europe is also Russia of Lavr Kornilov and the samizdat, Hungary of 1956 and Venerable József Mindszenty, Poland of Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński and Solidarność, Romania of Toma Arnăuțoiu and the victims of the mass purges of the Orthodox hierarchies, Bulgaria of the Goryani movement, and so on. Yet, the westernisation of those lands leads towards the homologation of a single thought, in the same way as the Marxist-Leninist assumptions, albeit with different methods and proposals. Anyway, non-negotiable assumptions!

Naturally, the concept of values and democracy has a different cultural, social and political development between the still-suffering East and the pleasure-loving (perhaps no longer) West. East pockets not only liberalism and unlimited individual freedoms but utilitarianism, consumerism, precariousness and inequality. It risks losing its Tradition, spiritual values and social interaction. It might not be a balanced, cooperative relationship. It might look like a cultural, social and political absorption. Not the best of democracy and liberality.

Europe is not reduced to the economic-commercial dimension of the European Union. Pope John Paul II spoke of a community of spirit, not of coins or bartering. Europe, not necessarily in political terms, is built on a foundation of symmetry between different peoples and proactive spiritual harmony. A doubt arises: did the preclusions the West motivated during the Cold War hide a contrast not so much ideological as of imperial territorial and economic supremacy?

Pope John Paul II, who wished for a united continent “from the Atlantic to the Urals,” already in 1982 from Santiago de Compostela, addressed Europe this way: “Rebuild your spiritual unity, in a climate of full respect for other religions and genuine freedoms … Find yourself again, be yourself.”[35]

REFERENCES

- Agadjanian, Alexander and Rousselet, Kathy (2005). Globalization and Identity Discourse in Russian Orthodoxy. In Roudometof, Victor, and Agadjanian, Alexander and Pankhurst, Jerry, Eastern Orthodoxy in a Global Age: Tradition Faces the Twenty-first Century, I Part East European Experiences, pp. 29-57. Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press.

- Baciu, Mihai (March 27th, 2002). Religion and change in central and eastern Europe. Retrieved from Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, https://assembly.coe.int/nw/xml/XRef/X2H-Xref-ViewHTML.asp?FileID=9678&lang=EN.

- Benovska-Sabkova, Milena and Altanov, Velislav (March 2009). Evangelical conversion among the Roma in Bulgaria: Between capsulation and globalization. Transitions, 48(2), 133-156.

- Cabada, Ladislav and Waisová, Šárka (2018). The Visegrad Group as an Ambitious Actor of (Central-) European Foreign and Security Policy. Politics in Central Europe, 14(2). doi: 10.2478/pce-2018-0006.

- Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (December 18th, 2000). Official Journal of the European Communities. Retrieved from https://www.europarl.europa.eu/charter/pdf/text_en.pdf.

- D’Agostino, Glauco (2010). Sulle Vie dell’Islam. Percorsi storici orientati tra dottrina, movimentismo politico-religioso e architetture sacre (Historical and Architectural Itineraries across the Muslim Countries). Rome, Italy: Gangemi.

- D’Agostino, Glauco (2017). Black Sea: Towards Areas of Influence on Moscow-Ankara Axis? Revistă de Geografie Politică, Geopolitică şi Geostrategie, 70(2). Bucureşti: Editura Top Form, Asociaţia de Geopolitica Ion Conea.

- D’Agostino, Glauco (June 2018). Tatarstan-Putin: A Crossed Challenge, London: Glimmer Publishing.

- D’Agostino, Glauco (July 4th, 2021). The Human Fraternity: Dialogue in Diversity Versus Cosmopolitanism. Retrieved from https://www.islamicworld.it/wp/the-human-fraternity-dialogue-in-diversity-versus-cosmopolitanism/

- European Parliament and Council of European Union (December 16th, 2020). Regulation (EU, Euratom) 2020/2092 on a general regime of conditionality for the protection of the Union budget. Official Journal of the European Union. Retrieved from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2020/2092/oj.

- Ferlat, Anne (2003). Neopaganism and new age in Russia. Folklore, 23, pp. 40-48. doi: 10.7592/FEJF2003.23.newage.

- Gauthier, François (2022). Religious change in Orthodox-majority Eastern Europe: from Nation-State to Global-Market. Theory and Society, 51, pp.177-210. doi:10.1007/s11186-021-09451-3.

- Gog, Sorin (March 2009). Post-Socialist Religious Pluralism. How do Religious conversions of Roma fit into the wider Landscape. From Global to Local Perspectives. Transitions, 48(2), 93-108. Retrieved from https://scholar.google.com/citations?view_op=view_citation&hl=en&user=CL-H78wAAAAJ&citation_for_view=CL-H78wAAAAJ:M3ejUd6NZC8C.

- Gog, Sorin (December 2016). Alternative Forms of Spirituality and the Socialization of a Self-Enhancing Subjectivity: Features of the Post-Secular Religious Space in Contemporary Romania. Studia Universitatis Babes-Bolyai Sociologia, 61(2), 97-124.

- Holy and Great Council (June 14th, 2016). Encyclical of the Holy and Great Council of the Orthodox Church. Retrieved from https://www.holycouncil.org/encyclical-holy-council.

- Huntington, Samuel Phillips (1996). The clash of civilizations and the remaking of world order. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

- John Paul II (Giovanni Paolo II) (November 9th, 1982). Atto Europeistico a Santiago de Compostela. Retrieved from https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/it/speeches/1982/november/documents/hf_jp-ii_spe_19821109_atto-europeistico.html.

- John Paul II (June 2nd, 1985). Slavorum Apostoli. Retrieved from https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_jp-ii_enc_19850602_slavorum-apostoli.html.

- John Paul II (Ioannes Paulus PP. II) (May 25th, 1995). Ut Unum Sint. On commitment to Ecumenism. Retrieved from https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_jp-ii_enc_25051995_ut-unum-sint.html#%242D.

- Kazharski, Aliaksei (May 11th, 2021). The Visegrád Group: an uneasy balance between East and West. Retrieved from European Consortium for Political Research, https://theloop.ecpr.eu/the-visegrad-group-an-uneasy-balance-between-east-and-west/

- Korosteleva, Elena A. (September 2016). The EU, Russia and the Eastern region: the analytics of government for sustainable cohabitation. Cooperation and Conflict, 51(3), doi:10.1177/0010836716631778.

- Koziej, Stanislaw (July 26th, 2018). The Visegrad Group and Europe’s security system: a story to watch. Retrieved from Geopolitical Intelligence Services, https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/visegrad-group/

- Leustean, Lucian N. (2018). Eastern Orthodoxy, Geopolitics and the 2016 ‘Holy and Great Synod of the Orthodox Church.’ Geopolitics, 23(1). doi: 10.1080/14650045.2017.1350843.

- Nitoiu, Cristian and Sus, Monika (2019). Introduction: The Rise of Geopolitics in the EU’s Approach in its Eastern Neighbourhood. Geopolitics, 24(1), 1-19. doi:10.1080/14650045.2019.1544396.

- Pänke, Julian (2019). Liberal Empire, Geopolitics and EU Strategy: Norms and Interests in European Foreign Policy Making. Geopolitics, 24(1), 100-123. doi: 10.1080/14650045.2018.1528545.

- Pew Research Center (May 10th, 2017). Religious Belief and National Belonging in Central and Eastern Europe. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2017/05/10/religious-affiliation/

- Pew Research Center (October 29th, 2018). Eastern and Western Europeans Differ on Importance of Religion, Views of Minorities, and Key Social Issues. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2018/10/29/eastern-and-western-europeans-differ-on-importance-of-religion-views-of-minorities-and-key-social-issues/

- Presidency of European Council (June 21st-22nd, 1993). Relations with the Countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Retrieved from https://www.europarl.europa.eu/enlargement/ec/pdf/cop_en.pdf.

- Pyzik, Agata (June 20th, 2014). The Baltics: what’s wrong with being ‘east’ anyway? Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jun/20/lithuania-latvia-estonia-baltics-guardian-new-east.

- Russian Orthodox Church, Department for External Church Relations (2008). The Russian Orthodox Church’s Basic Teaching on Human Dignity, Freedom and Rights. Retrieved from https://old.mospat.ru/en/documents/dignity-freedom-rights/iii/

- Tchakarova, Velina (2017). Competing geopolitical approaches towards Eastern Europe. AIES (Austria Institut für Europa und Sicherheitspolitik). Retrieved from https://www.aies.at/download/2017/AIES-Fokus_2017-04.pdf.

- United Nations, Department for General Assembly and Conference Management (n.d.). Regional groups of Member States. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/dgacm/en/content/regional-groups, achieved March 2nd, 2023.

- Vondra, Alexandr (May 31st, 2018). Cold war between Visegrad and Brussels. Retrieved from https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/angry-brussels/

- Yannoulatos Anastasios, Archbishop (2003). Facing the World. Orthodox Christian Essays on Global Concerns. Yonkers, New York: SVS (St Vladimir’s Seminary) Press.

- Yelensky, Victor (March 7th, 2006). Globalization, Nationalism, and Orthodoxy: The Case of Ukrainian Nation Building. In Roudometof, Victor, and Agadjanian, Alexander and Pankhurst, Jerry, Eastern Orthodoxy in a Global Age: Tradition Faces the Twenty-first Century, pp. 144-177. Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press.

[1] Samuel Phillips Huntington (1996). The clash of civilizations and the remaking of world order, Ch. 7 Core States, Concentric Circles, and Civilizational Order, p. 158. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

[2] John Paul II (June 2nd, 1985). Slavorum Apostoli. Ch. VII The Significance and Influence of the Christian Millennium in the Slav World. Retrieved from https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_jp-ii_enc_19850602_slavorum-apostoli.html.

[3] Ioannes Paulus PP. II (May 25th, 1995). Ut Unum Sint. On commitment to Ecumenism. Ch. II The Fruits of Dialogue. Retrieved from https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_jp-ii_enc_25051995_ut-unum-sint.html#%242D.

[4] United Nations, Department for General Assembly and Conference Management (n.d.). Regional groups of Member States. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/dgacm/en/content/regional-groups, achieved March 2nd, 2023.

[5] Agata Pyzik (June 20th, 2014). The Baltics: what’s wrong with being ‘east’ anyway? Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jun/20/lithuania-latvia-estonia-baltics-guardian-new-east.

[6] Velina Tchakarova (2017). Competing geopolitical approaches towards Eastern Europe. AIES (Austria Institut für Europa und Sicherheitspolitik). Retrieved from https://www.aies.at/download/2017/AIES-Fokus_2017-04.pdf.

[7] Cristian Nitoiu and Monika Sus (2019). Introduction: The Rise of Geopolitics in the EU’s Approach in its Eastern Neighbourhood. Geopolitics, 24(1), 1-19. doi:10.1080/14650045.2019.1544396.

[8] Elena A. Korosteleva (September 2016). The EU, Russia and the Eastern region: the analytics of government for sustainable cohabitation. Cooperation and Conflict, 51(3), doi:10.1177/0010836716631778.

[9] Presidency of European Council (June 21st-22nd, 1993). Relations with the Countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Retrieved from https://www.europarl.europa.eu/enlargement/ec/pdf/cop_en.pdf.

[10] Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (December 18th, 2000). Official Journal of the European Communities. Retrieved from https://www.europarl.europa.eu/charter/pdf/text_en.pdf.

[11] Pew Research Center (October 29th, 2018). Eastern and Western Europeans Differ on Importance of Religion, Views of Minorities, and Key Social Issues. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2018/10/29/eastern-and-western-europeans-differ-on-importance-of-religion-views-of-minorities-and-key-social-issues/

[12] Anastasios Yannoulatos, Archbishop (2003). Facing the World. Orthodox Christian Essays on Global Concerns. Yonkers, New York: SVS (St Vladimir’s Seminary) Press.

[13] Glauco D’Agostino (July 4th, 2021). The Human Fraternity: Dialogue in Diversity Versus Cosmopolitanism. Retrieved from https://www.islamicworld.it/wp/the-human-fraternity-dialogue-in-diversity-versus-cosmopolitanism/

[14] Holy and Great Council (June 14th, 2016). Encyclical of the Holy and Great Council of the Orthodox Church. Retrieved from https://www.holycouncil.org/encyclical-holy-council.

[15] Alexander Agadjanian and Kathy Rousselet (2005). Globalization and Identity Discourse in Russian Orthodoxy. In Victor Roudometof, Alexander Agadjanian, and Jerry Pankhurst, Eastern Orthodoxy in a Global Age: Tradition Faces the Twenty-first Century, I Part East European Experiences, pp. 29-57. Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press.

[16] Russian Orthodox Church, Department for External Church Relations (2008). The Russian Orthodox Church’s Basic Teaching on Human Dignity, Freedom and Rights, III. 2 Human rights in Christian worldview and in the life of society. Retrieved from https://old.mospat.ru/en/documents/dignity-freedom-rights/iii/

[17] Glauco D’Agostino (June 2018). Tatarstan-Putin: A Crossed Challenge, Ch. 1, p. 6. London: Glimmer Publishing.

[18] Mihai Baciu (March 27th, 2002). Religion and change in central and eastern Europe. Retrieved from Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, https://assembly.coe.int/nw/xml/XRef/X2H-Xref-ViewHTML.asp?FileID=9678&lang=EN.

[19] François Gauthier (2022). Religious change in Orthodox-majority Eastern Europe: from Nation-State to Global-Market. Theory and Society, 51, pp.177-210. doi:10.1007/s11186-021-09451-3.

[20] Victor Yelensky (March 7th, 2006). Globalization, Nationalism, and Orthodoxy: The Case of Ukrainian Nation Building. In V. Roudometof, A. Agadjanian, and J. Pankhurst, Eastern Orthodoxy in a Global Age, cit., pp. 144-177.

[21] Sorin Gog (March 2009). Post-Socialist Religious Pluralism. How do Religious conversions of Roma fit into the wider Landscape. From Global to Local Perspectives. Transitions, 48(2), 93-108. Retrieved from https://scholar.google.com/citations?view_op=view_citation&hl=en&user=CL-H78wAAAAJ&citation_for_view=CL-H78wAAAAJ:M3ejUd6NZC8C.

[22] Anne Ferlat (2003). Neopaganism and new age in Russia. Folklore, 23, pp. 40-48. doi: 10.7592/FEJF2003.23.newage.

[23] Milena Benovska-Sabkova and Velislav Altanov (March 2009). Evangelical conversion among the Roma in Bulgaria: Between capsulation and globalization. Transitions, 48(2), 133-156.

[24] Sorin Gog (December 2016). Alternative Forms of Spirituality and the Socialization of a Self-Enhancing Subjectivity: Features of the Post-Secular Religious Space in Contemporary Romania. Studia Universitatis Babes-Bolyai Sociologia, 61(2), 97-124.

[25] Ladislav Cabada and Šárka Waisová (2018). The Visegrad Group as an Ambitious Actor of (Central-) European Foreign and Security Policy. Politics in Central Europe, 14(2). doi: 10.2478/pce-2018-0006.

[26] Alexandr Vondra (May 31st, 2018). Cold war between Visegrad and Brussels. Retrieved from https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/angry-brussels/

[27] Aliaksei Kazharski (May 11th, 2021). The Visegrád Group: an uneasy balance between East and West. Retrieved from European Consortium for Political Research, https://theloop.ecpr.eu/the-visegrad-group-an-uneasy-balance-between-east-and-west/

[28] Julian Pänke (2019). Liberal Empire, Geopolitics and EU Strategy: Norms and Interests in European Foreign Policy Making. Geopolitics, 24(1), 100-123. doi: 10.1080/14650045.2018.1528545.

[29] European Parliament and Council of European Union (December 16th, 2020). Regulation (EU, Euratom) 2020/2092 on a general regime of conditionality for the protection of the Union budget. Official Journal of the European Union. Retrieved from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2020/2092/oj.

[30] Stanislaw Koziej (July 26th, 2018). The Visegrad Group and Europe’s security system: a story to watch. Retrieved from Geopolitical Intelligence Services, https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/visegrad-group/

[31] Pew Research Center (May 10th, 2017). Religious Belief and National Belonging in Central and Eastern Europe. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2017/05/10/religious-affiliation/

[32] Glauco D’Agostino (2017). Black Sea: Towards Areas of Influence on Moscow-Ankara Axis? Geopolitica. Revistă de Geografie Politică, Geopolitică şi Geostrategie, 70(2). Bucureşti: Editura Top Form, Asociaţia de Geopolitica Ion Conea.

[33] Lucian N. Leustean (2018). Eastern Orthodoxy, Geopolitics and the 2016 ‘Holy and Great Synod of the Orthodox Church.’ Geopolitics, 23(1). doi: 10.1080/14650045.2017.1350843.

[34] Glauco D’Agostino (2010). Sulle Vie dell’Islam. Percorsi storici orientati tra dottrina, movimentismo politico-religioso e architetture sacre (Historical and Architectural Itineraries across the Muslim Countries), Ch. 7 L’Islam e il nazionalismo ideologico, p. 205. Rome, Italy: Gangemi.

[35] Giovanni Paolo II (November 9th, 1982). Atto Europeistico a Santiago de Compostela. Retrieved from https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/it/speeches/1982/november/documents/hf_jp-ii_spe_19821109_atto-europeistico.html.