By Glauco D’Agostino

While awaiting the expected face-to-face meeting between Presidents, Joe Biden and Xi Jinping, Islamic World Analyzes offers this article by Glauco D’Agostino on the various aspects of the competition for a new world order. The contribution, written before the Gaza crisis broke out on the international scene, is linked to this event not so much because on this occasion, too, a direct clash between the two giants could be envisaged but because it could outline a geopolitical turning point in the direction of new arrangements in global governance. In this sense, a U.S. military commitment in the Asia-Pacific area would see Washington active on a third front after those opened in Ukraine and the Middle East. A considerable gamble?

Abstract

The all-out U.S.-China challenge is now the catalyst for global attention, especially for its progress. The proposed study is based on institutional documents, declarations and assessments in official papers, essays, specialised journals and press articles dealing with interpreting the contenders’ intentions in the most sensitive area, Asia-Pacific. What consequences will the loss of Washington’s hegemony have in passing from a unipolar to a multipolar world? Do the historic alliances still make sense, those generated eighty years ago by the Cold War or that arose after the fall of the Berlin Wall? Are the celebration of ideologies and the End of History myth still effective in facing the dares of a highly technological society? Perhaps the real unknown factor is China since it embarked on the path of economic opening up to world markets. The West’s claim to dominate its behaviour has collided with the single-mindedness of men and institutions determined to compete on one of the cornerstones of Euro-Atlantic thought, economic and financial competition.

The analysis is ruled on qualified sources from opposing fields and, as well, the opinions of “third parties” (Asian and not Asian) experiencing this transitional era with apprehension and reliance on the leadership’s common sense. The results are consistent with two alternative visions of the strategy for the global order, one founded on the dissuasive power of military structures and the other built on the emancipation from the dependencies of alliances. However, none underestimate the dollar’s strength as a global power tool.

Keywords: China, United States of America, Asia-Pacific, India, ASEAN, Global Civilization Initiative, Summit for Democracy.

***

Foreword and purposes

The design of this report is part of broader analyses led on large-scale geopolitical dynamics, in particular, in the Middle East, South-Central Asia, the Maghreb and the Sahel. These studies also aim to monitor the state of health of geopolitics as a discipline. Today, it risks switching from a doctrine to understanding how territorial features (physical-geographical, anthropic, relational, political-economic) affect the multiple geo-strategies of involved international actors to a mere propaganda tool at the service of dominant subjects’ anxiety for power. In the era of global communication, the narration of historical (even current) events determining the future of the overall order is at stake.

Among others, we can glimpse two decisive dangers: the perception of localised warlike events as peculiar and transient contrasts instead of the exploitation of clashes between proxies for the overall leadership of the respective conferring parties; and the information gerrymander to influence public opinion in the directions desired by the guardians of the dominant arrangements. The former leads to face the topic of preserving consolidated systems after the war events of the last century; the latter to the mass media control aimed at conditioning judgements and their consequent political attitudes.

In particular, the history of the last thirty years has led to the alteration of the geopolitics nature towards the role of ideological support for very partial conceptions deemed universal and indisputable: a totalitarian, self-referential world vision, without any distinction to “other” ideal and behavioural postulates and all aimed at a utopian cosmopolitanism. All this to support appreciable values and principles, but above all, functional to the dominance of peoples, territories, relationships, resources and having economic and technological availability as an instrument.

Here’s the context. The competition in the Asia-Pacific we are dealing with here is just one episode of a much broader confrontation with far more relevant specifications.[1] It may correspond to Alfred Thayer Mahan’s geopolitical conceptions of maritime control. The Central Asian control dispute would also meet Halford Mackinder’s Eurasian vision. Today, the protagonists would always be the same: the United States and China. What changes are the quarrel target and the operation methodology, in practice, the geopolitics reading and the new geo-strategies formalisation. The introduction of Artificial Intelligence seems to have disoriented one of the two contenders. The ruling user of that economic and technological availability as the winning asset seems to have changed. Is there such an awareness?

The framework of the findings recorded in this limited examination is varied and composite, depending on the attitudes of the protagonists or analysts: from the scaremonger and prophet of doom to the more proactive and realistic ones. Sometimes ideological sediment remains, yet, placing an alleged ethical judgement at the basis of international politics. Anti-Chinese and anti-Russian aversion has taken the place of anti-Islamic wars. Nevertheless, the awareness shines through that past ideological disputes are no longer sufficient to stop the participation request from developing people and communities. Perhaps ethical judgment should also cover this instance. But the claim correctness is not in question here, rather the ability to intervene in global decision-making processes in defence of one’s geo-political interests, until now sacrificed for the benefit of others.

Technological tools (remote control, Artificial Intelligence, quantum applications) are increasingly changing the methods of geopolitical operations, which today are less connected to the physical domain of the territory. Even the so-called “hybrid wars” have taught that the military hegemony of an area is unrealistic without the consent of involved local actors. Afghanistan and the Sahelo-Saharan area bear witness to this. Beyond interventionist or, conversely, pacifist rhetoric, we need new geo-strategies that are less aggressive and more open to actual international cooperation based on mutual interests to share. Perhaps the Belt and Road Initiative is scary because of this, but Iran and Saudi Arabia, historical adversaries, do not go down the path of forced inhibition. The 21st-century competition takes place on these parameters.

One more note concerning the spectrum of this report relates to the use of language and its influence on public opinion. Communication is of fundamental importance at a time when Artificial Intelligence is about to open up new horizons in this field, a minefield according to Western countries. The U.S. and the E.U., while attending the 2021 Trade and Technology Council and with unambiguous references to China, raised concerns about its use for classification systems aimed at large-scale social control. Heterogony of ends, one could say, for those who have based their geopolitical influence on communication control.

The improper and methodologically incorrect use of terms such as “dictator,” “massacre,” “axis of evil,” “terrorist,” and “jihādist,” for instance, belongs to political propaganda and not to geopolitics. Even the systematic suspicions about using tools you can’t handle properly belong to this case. The fairness of using sound independent sources addresses the same issue. Maybe it’s not enough if a piece of news comes from the White House or the State Department. It could also be instrumental in fake news.

All that is what this umpteenth study experience has proposed in the context of a broader observation run over time and in several territorial and disciplinary fields.

Introduction

“My gut tells me we will fight in 2025. Xi secured his third term and set his war council in October 2022. Taiwan’s presidential elections are in 2024 and will offer Xi a reason. United States presidential elections are in 2024 and will offer Xi a distracted America. Xi’s team, reason, and opportunity are all aligned for 2025.” The warning, rather than a prediction, comes from none other than Gen. Michael A. Minihan, head of Air Mobility Command of the U.S. Air Force.[2] Yet, at the 2022 G20 Bali Summit, Joe Biden and Xi Jinping also ruled out a return to the Cold War.

Minihan’s seems to be a sign of desperation rather than hope for the States, now entangled in a spiral of continuous belligerence, which since the Fall of the Berlin Wall has seen them intervene in the most varied theatres of war, from Panama to the Gulf, from Somalia to former Yugoslavia, from Haiti to Afghanistan, from Yemen to Iraq, from Pakistan to Libya, from Uganda to Niger and Syria. All of these countries were allegedly threatening Washington’s interests. Today is China’s turn, whose last armed conflict, excluding the skirmishes with India, was resolved in 1991 with Vietnam.

The geopolitical attitude of Beijing, so threatening according to Washington, is substantiated by the mind of Henry Huiyao Wang, Founder and President of the Center for China and Globalization (CCG): “China is the only third party to come out of this direct fight and has economic ties with Russia, Ukraine, the EU and the US.”[3] Meanwhile, the White House, through the AUKUS trilateral security partnership signed with the United Kingdom, is working to convey the technology for the construction of nuclear-powered submarines to Australia, altering the geography of the Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zones (NWFZ) in the Southern Hemisphere and inducing an escalation in the arms race.

Where are the United States and China going? What role do they play in the Pacific, and with what prospects? Is it enough to adopt the generic “national interest” concept to refer to the equally generic “international order”? Perhaps the sorry experience of the Eight-Nation Alliance that invaded China at the beginning of the last century and determined its dependence on the West cannot be repeated.

Chinese Dream or challenges to Euro-Atlantic security?

The hyper-quoted phrase about the trembling world after China waking, ascribed to Napoleon via Lenin and Alain Peyrefitte, seems to suddenly materialise in current events, leaving its literary and scenographic nature and entering this decade the 21st-century geopolitical reality at full speed.

Still, the preparation was meticulous. Under the banner of Artificial Intelligence, China represents an idea of the future as opposed to Western lethargy.[4] According to Asia Times’ Business Editor David Goldman, China will surpass the US as a superpower since it aims to control the key technologies of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, especially artificial intelligence applications to large data sets.[5]

And so the Chinese Dream, evoked in 2012 by Xi Jinping over the Road to National Rejuvenation exhibit at the National Museum of China in Tian’anmen Square, continues its journey.[6] As for its motivations, the analysis by Xiāng Lánxīn, Professor of History and International Relations at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies (IHEID) in Geneva, is interesting. He identified some Chinese dreams: to restore the past glory of the state and the Imperial memory of a modern, wealthy and mighty China; and to maintain social stability, making Chinese people proud and happy.

In the inaugural session of the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of China, President Xi was clear: ensure the nation leads the world in terms of composite national strength and international influence. And, more recently, at the High-level Meeting CPC-World Political Parties, held in Beijing last 15 March, while proposing the Global Civilization Initiative, he stressed the need for countries to refrain from imposing their own values or models on others and fully harness the relevance of their histories and cultures to the present times.[7]

The United States, well aware of the Chinese President’s declared intention to create a new regional order led by Asian nations, replies to the Global Civilization Initiative with the Summit for Democracy, which not by chance took place this year two weeks after the above-mentioned international meeting in Beijing. Against respect for the values of “other civilizations”, Biden contrasts supporting democratic institutions, human rights, the rule of law, and media freedom.

NATO’s new Strategic Concept adopted at the Madrid Summit in June 2022 is more explicit when, in an unprecedented attack on China, it claims that “it strives to subvert the rules-based international order” and “the deepening strategic partnership between the People’s Republic of China and the Russian Federation and their mutually reinforcing attempts to undercut the rules-based international order run counter to our values and interests.”[8] Even the direct intervention of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization in the Pacific quadrant represents a novelty and a worrying surge due to its military nature. And the reasons for this stance are even more so: “the systemic challenges posed by the PRC to Euro-Atlantic security.” As if to say NATO will not allow the birth of a regional leader in the Pacific to challenge the alleged American predominance.

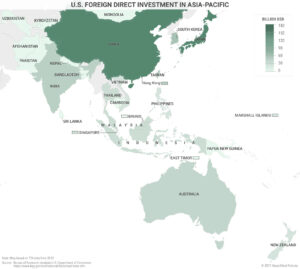

Beyond the data on the levels of trade and investment, Washington is aware of the decline of its influence in the region[9] and pictures it in a Chinese attack on the international order, as if the increased importance of Asian players conflicted with international law. Of course, China is the beneficiary of it since it has promoted and created adequate bilateral cooperation between countries of the area, following the geopolitical doctrine that inspires it for partnerships that do not target an assumed enemy or any third party.[10]

Diplomatic strategy versus military strategy

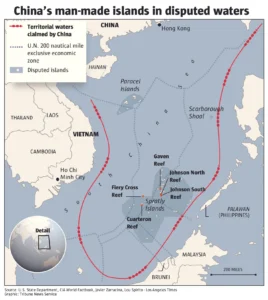

The goal that pits the two superpowers is the control of the entire Asian maritime trade.[11] The framework explains the increasing attention the White House strategy of President Obama and his Secretary of State Hillary Clinton placed to the region since 2011 and the consequent Chinese response in the South China Sea through its maritime dynamism.

Leaving aside the conspiracy theory about a Chinese “grey zone” strategy, Beijing intends to pursue a diplomatic rather than a military strategy to achieve its goals. An example is the security pact with the former British Protectorate of the Solomon Islands, South Pacific, which since April last year, has been allowing China to make ship visits, carry out logistical replenishment, and have stopover and transition. Washington, in turn, responded in February this year by reopening its embassy in Honiara, on the Guadalcanal island, after 30 years. Perhaps historical pride (the Guadalcanal campaign) or geopolitical realism, the fact is that the Americans do not intend to leave China a space in the Pacific for which they feel are responsible.

What is sure, the Asia-Pacific area will not have (and does not already have) a single hegemonic power in an out-and-out transition from a unipolar to a multipolar world. As reported in his interview with The Atlantic magazine,[12] Stephen Biddle, Professor at the School of International and Public Affairs, Columbia University, is convinced of it.

But President Biden was already convinced of it when he launched his Interim National Security Strategic Guidance. After recognising that the distribution of power across the world is changing, he also stated: “China … is the only competitor potentially capable of combining its economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to mount a sustained challenge to a stable and open international system.”[13] Elbridge Colby, a co-founder of The Marathon Initiative for preparing the U.S. for an era of sustained big power competition, is even more trenchant. In his recent book, The Strategy of Denial, he wrote: “Even though U.S. military dominance over China is certainly desirable, it is simply no longer attainable.”

American concerns were followed by the firm attitudes of the European Union from the E.U. Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific, in particular, the emphasis on the importance of a meaningful European naval presence in the Indo-Pacific.[14] And, among the most determined European countries, Germany of Olaf Scholz, in office from the end of 2021, stood out. Many analysts believe the Chancellor’s government, which supports anyway the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) proposed to encourage investment between the E.U. and China, is much less sympathetic towards Beijing than his predecessor Angela Merkel, to the point of considering China as a systemic rival.[15]

The U.S. and E.U. are taking countermeasures against China’s engagement in the Asia-Pacific, intensifying their presence in the region through trade agreements, but also with approaches covering security and military involvement of their allies and the prospect of sharing intelligence, exercises or even joint command centres. In particular, President Biden intends to co-opt E.U. and NATO into a safeguard umbrella for his allies in the Pacific. The White House relies on the role of Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand, the Philippines, and Thailand; and, to underline the partnership with non-member states of the area, at the 32nd NATO Summit in Madrid last year, the first four mentioned countries were invited for the first time to participate in the proceedings.

Of course, the strong bond connecting the United States to Taiwan lies under the Taiwan Relations Act, which since 1979 has been regulating non-diplomatic relations between the two governments.[16] Among the thousands of tensions shaking daily diplomacy and public opinion on the military situation around the island and with the recent supply of defensive weapons to Taipei, President Biden assures that the United States does not support changes in the status quo from either side, closing both the probability of Taipei’s unilateral independence and a Chinese annexation by force.

Relations with India and ASEAN

Washington Indo-Pacific strategy, formalised by President Trump in 2019 with the document A Free and Open Indo-Pacific,[17] calls together “allies, partners, and regional institutions such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the Mekong states, the Pacific Island countries, Taiwan,” but reserves the appellation of “our strategic partner” to India. According to the White House intentions, New Delhī should still be a pillar of American policy in the Pacific since it has already adhered to geopolitical instruments for the containment of China, such as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) together with the U.S., Japan and Australia, and the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity initiative including Japan, South Korea and Australia.

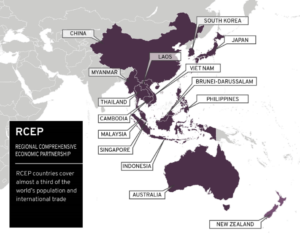

However, India, which anyway shows no interest in possible collaborations with NATO, does not intend to be a tributary of American interests, and it counterbalances those adhesions by membership in the Russo-Chinese-led Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) and the BRICS, which make no secret of considering alternatives to the G7 governance pattern. Delhī shows caution in its attitude towards Beijing, which deems QUAD as an informal anti-China security group, and towards Moscow, with which it does not want to interrupt its historical security ties.[18] And it demonstrates scepticism towards multilateral trade agreements led by Japan (the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, CPTPP, heir to the never-ratified Trans-Pacific Partnership, TPP) or by ASEAN (the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, RCEP).

The relationship with ASEAN has right been at the heart of China’s and the U.S. appetites, the former directly through the RCEP since 2020 and the latter through the 2022 ASEAN-U.S. Comprehensive Strategic Partnership.[19] Beijing and Washington are, respectively, the ASEAN region’s largest trading partner and its highest source of foreign direct investment. But, if trade opportunities open up for Beijing throughout the Pacific area, that Asian political-economic entity is the essential gateway for Washington to support its resolution of regional-led strategic balances (Sexton, 2022).

In 1996, ASEAN promoted the need for a regional Code of Conduct (CoC) in the South China Sea to mitigate Chinese claims in the area.[20] Twenty-seven years after that proposal by the foreign ministers of the member countries, no agreement has been reached. The legal framework is complicated, but diplomatic negotiations with the concerned states are even more so.

Analysts are also divided over the interpretations of the story. Ian Storey, a senior fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore, says: “Should the CoC be legally binding? Most ASEAN member states appear to support that, but China is opposed.” Sourabh Gupta, a resident senior fellow at the Institute for China-America Studies (ICAS) in Washington, is more problematic when arguing that Beijing believes “there should be no role for external companies in key areas of marine economic cooperation, primarily oil and gas development, nor any joint military exercising with extra-regional states.” Basically, according to B.A. Hamzah, the Director of the Centre for Defence and International Security Studies at the National Defence University of Malaysia, Beijing’s logic is: “If the CoC cannot keep the U.S. military at bay, why should Beijing ratify it? To China, ASEAN has been working as a proxy for Washington.”[21]

The analysis by Digby James Wren, senior special adviser at the International Relations Institute, Royal Academy of Cambodia, is incisive: “The US’ efforts to drive a wedge between ASEAN and other economies as well as divide ASEAN has prompted some ASEAN member states to delay or refuse to sign the China-sponsored South China Sea Code of Conduct and develop closer diplomatic and commercial ties with China’s Taiwan.”[22] A realistic view is that of Bilahari Kausikan, former Singaporean Ambassador-at-Large: “The CoC is an instrument being used by both sides, not just China, to manage the relationship. When the relationship is tense, we don’t discuss the CoC. When the relationship improves, we pretend to discuss the CoC.”

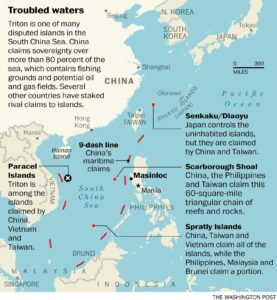

The territorial disputes China is involved in concern:

- its function as de jure or de facto administrator (e.g. the Paracel Islands, contested by Vietnam and Taiwan, as well, and the Scarborough Shoal, also claimed by the Philippines and Taiwan);

- its role as a military investor deemed illegal, as well as other military forces from Malaysia, Vietnam, Taiwan or the Philippines (as on the Spratly Islands);

- its claim of islands falling within Beijing’s nine-dash line “arising from historical practices before the formation of modern international laws of the sea.”[23] It overlaps with the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) claims of Taiwan, the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Sultanate of Brunei Darussalam;

- the belonging of a territory to one of its EEZs, such as the Socotra Rock in the Yellow Sea, contested by South Korea.

Other territorial disputes in South-East Asia involve the region’s countries among themselves but without ASEAN directly intervening in the resolution, which is instead devolved into bilateral negotiations. Among these, the following stand out:[24]

- the definition of Indonesia and Malaysia’s territorial waters in the Sulawesi Sea and the southernmost part of the Strait of Malacca;

- the delimitation of the Indonesian EEZ boundary line with Vietnam and the Philippines;

- the delineation of the continental shelf between Vietnam and Malaysia;

- the definition of ownership over some shoals in the Spratly Islands, contested by Vietnam and the Philippines;

- the dispute between Malaysia and the Philippines over much of the eastern part of the State of Sabah, belonging to the Malaysian federal state and claimed by the Philippines as the successor to the Sultanate of Sulu.

Final remarks

Two months before China formally joined the WTO, the United States and its allies invaded its neighbouring country Afghanistan and two years earlier bombed the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade “by mistake.” Someone could maliciously see a link in it, namely that of preventive warnings at a time Beijing entered the competition in global trade. Those were the years of Jiang Zemin, who continued the reforming work begun by Deng Xiaoping, and the start of George W. Bush’s warlike season that would lead to the 2008 financial crisis.

Despite its Non-market economy status recognised by the WTO access protocols, the process of opening up the economy began for China with the “deregulation” in the state industry sectors and the projection on the market of foreign investments in all sectors, leading China to the world’s first place in the GDP (PPP assessed in Int’l$) and in international trade, surpassing the US by 6,000 and 9,000 billion dollars respectively.[25] What worries Washington today is, in terms of the world economy, also the Chinese predominance in the supply of rare-earth elements and the production of electronics components, personal computers, air conditioners and telephones; in terms of geopolitics, its ability to involve dozens of countries in the Belt and Road Initiative, following Xi’s strategy according to which countries can also be partners if they seek common ground while reserving differences.[26]

How to face this awakening of China? It doesn’t seem the White House has clear ideas about this. If the ground is the Cold War, as President Xi denounces against Washington, for the United States, confrontation is a non-runner. The pacts signed in Yalta and Potsdam with the Soviet Union provided a tacit understanding of sharing the world in two blocs based on the balance of armaments. The challenge Beijing is launching is built on the economic competition field, a cornerstone of Western thought and where the U.S. has rooted its hegemony.

A rallying call on the ideological commitment to defend democracy and against authoritarianism may not be enough for President Biden. Exhibiting these arguments is already an acknowledgement of surrender on a pragmatism level. And so, while Xi imperturbably follows his strategic planning road to 2049, aggregating more and more countries around the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, the centres of American power are discussing whether the opponent should be identified in Beijing (as Trump predicted) or in Moscow (as in fact, Biden assures). Unsettled, now the Administration finds itself with two fronts open simultaneously on the Black Sea and the Pacific and relies on NATO (which Trump had practically resized) to open war scenarios in the East. However, between scandals and trials, the backdrop could change in October next year when the two enemies (rather than antagonists) will compete in the polls for a dispute it is hoped will have, this time, shared results, at least in terms of rule-of-law acceptance.

America no longer has the resources to bear the cost of world development it has led for 30 years. Its empire is falling due to a lack of credibility rather than rival aggressiveness,[27] as had already happened to the U.K. after WWII, with the inevitable replacement of the leadership on the seas. But over the control of the sea is once again being played the fate of the world after 80 years.

This lack of credibility is affecting the dollar, the tool of the undisputed power of the U.S. domain. But new Chinese activism is also appearing on this terrain and is slowly making inroads into the economic-financial system. The rénmínbì, whose internationalisation is believed to be gradual but inevitable, appears as one of the most active currencies by value for payments worldwide. Sure, it cannot currently compete with the power of the dollar or the euro, which jointly make up three-quarters of international transactions. However the cases of deviation from the current system are growing. For instance:[28]

- China has already established agreements with more than 25 countries to settle mutual rénmínbì payments between companies and financial institutions with direct access to domestic (China National Advanced Payment System, CNAPS) and international (Cross Border Interbank Payment System, CIPS) payment systems.

- After Bank Indonesia’s call in October last year to reduce Indonesian financial markets’ reliance on the U.S. dollar, a two-way payment system based on national currencies is making its way, as already agreed by China, Japan, Thailand, Malaysia, and such as Singapore and the Philippines planning to do.

- Following Saudi-Chinese talks in March 2022, officials from both countries are considering pricing some oil sales in rénmínbì instead of U.S. dollars.

- India, which has not joined the sanctions against Russia, has disclosed the possibility of using the rénmínbì for imports of its oil. India considers the New Development Bank (NDB), proposed by Delhī as a multilateral development entity among the BRICS countries, a regional aggregation tool for promoting local currencies.

- Last year, Sberbank, one of the dominant lending institutions in Russia, announced the issuance of rénmínbì

- Earlier this year, the Central Bank of Brazil signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the People’s Bank of China to establish rénmínbì as a commercial and financial transaction tool.

The last examples mentioned relate to India, Russia and Brazil, three of the BRICS countries. The reported actions result from the Ufa Declaration, which in July 2015 concluded the 7th BRICS Summit with the exhortation addressed to member countries to encourage the use of national currencies in mutual transactions (D’Agostino, 2022). Eight years later, a theorisation with a political flavour is still on the way to being translated into concrete realisation. And yet, the proposing international aggregation is gaining strength, as, in line with Xi’s New Type of Security Partnership, it constitutes neither an alliance nor an ideological front, while requests for membership are intensifying (from the Islamic Republic of Iran to Algeria, from Egypt to the United Arab Emirates, from Ethiopia to Argentina) and interest in membership is growing (more than 25 countries, most of which have an Islamic majority and half are Asian).

Neither the White House nor the world’s major financial institutions seem to officially care about it since the dollar constitutes the foreign exchange reserves of the states. “The dollar is our currency, but it’s your problem,” said 1971 U.S. Secretary of the Treasury John Connally Jr. to his Group of Ten interlocutors. But perhaps the multipolar world is already in sight, and nobody knows if it will not be without jolts.

REFERENCES

Al Mayadeen. “Bank Indonesia calls against payments in US Dollars.” October 15th, 2022. https://english.almayadeen.net/news/economics/bank-indonesia-calls-against-payments-in-us-dollars.

Bajrektarevic, Anis H. “Unavoidability of Sino-American Rift: History of Strategic Decoup.” International Institute for Middle East and Balkan Studies (IFIMES), December 25th, 2021. https://mailchi.mp/753db3b52d87/analysis-prof-dr-anis-h-bajrektarevic-unavoidability-of-sino-american-rift-history-of-strategic-decoupling?e=9ba89dd268.

Biden, Joseph R., Jr. “Interim National Security Strategic Guidance.” The White House, March 2021. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/NSC-1v2.pdf, 7-8.

Cash Treasury Management File. “BRICS countries keen to develop own payment systems – Industry roundup: 23 June.” June 23rd, 2022. https://ctmfile.com/story/brics-countries-keen-to-develop-own-payment-systems-industry-roundup-twenty-third-june.

China.org.cn. “A New Type of Security Partnership.” November 4th, 2021. http://www.china.org.cn/english/china_key_words/2021-11/04/content_77851554.html#:~:text=A%20New%20Type%20of%20Security%20Partnership%20The%20Eighth,governance%20responding%20to%20the%20development%20of%20the%20times.

Colley, Christopher K. “The Emerging Great Power Triangle: China, India and the United States in the Indian Ocean Region.” In Essays on the Rise of China and Its Implications, edited by Abraham M. Denmark and Lucas Myers, 59-86. Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, 2021.

Council of the European Union. “EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific.” April 16th, 2021. https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-7914-2021-INIT/en/pdf.

D’Agostino, Glauco. “Global Governance: Is Asia’s Time Coming?” Geopolitica. Revistă de Geografie Politică, Geopolitică şi Geostrategie, no. 96-97 (4/2022): 49-70, Bucureşti: Top Form. https://www.geopolitic.ro/2023/02/global-governance-asias-time-coming/

D’Agostino, Glauco. “Tehrān towards Beijing and Moscow: Strategic alliances and overcoming divergences,” Geopolitica, n. 92-93 (1/2022), Bucureşti: Top Form. https://www.geopolitic.ro/2022/02/tehran-towards-beijing-moscow-strategic-alliances-overcoming-divergences/

Department of State, United States of America. “A Free and Open Indo-Pacific. Advancing a Shared Vision.” November 4th, 2019. https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Free-and-Open-Indo-Pacific-4Nov2019.pdf.

Fiorina, Jean-François. “Suite de mon recueil de phrases géopolitiques (aujourd’hui la Chine)”. LinkedIn, April 26th, 2022.

Geopolitical Report ISSN 2785-2598. “Can Saudi Arabia Switch From The US Dollar To The Chinese Yuan?” no. 30 (4/2023), Rome, Italy: SpecialEurasia.

Can Saudi Arabia switch from the US dollar to the Chinese yuan?

Hayton, Bill. “After 25 Years, There’s Still No South China Sea Code of Conduct.” Foreign Policy, July 21st, 2021.

After 25 Years, There’s Still No South China Sea Code of Conduct

International Monetary Fund. “World Economic Outlook Database.” April 2023. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2023/April.

Kohlmann, Thomas. “Opinion: Germany makes long overdue economic pivot in Asia.” Deutsche Welle, November 19th, 2022. https://www.dw.com/en/opinion-germany-makes-long-overdue-economic-pivot-in-asia/a-63804530.

Lamothe, Dan. “U.S. general warns troops that war with China is possible in two years.” The Washington Post, January 27th, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/2023/01/27/us-general-minihan-china-war-2025/

Mandeville, Laure and Goldman, David P. “AT tells Le Figaro why China is winning the tech war.” Asia Times, December 14th, 2020.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. “Xi Jinping Attends the CPC in Dialogue with World Political Parties High-level Meeting and Delivers a Keynote Speech.” March 16th, 2023. https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/zxxx_662805/202303/t20230317_11043656.html.

NATO / OTAN. “NATO 2022 Strategic Concept.” June 29th, 2022. https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2022/6/pdf/290622-strategic-concept.pdf.

Nguyen, Hong Thao. “Malaysia’s New Game in the South China Sea.” The Diplomat, December 21st, 2019. https://thediplomat.com/2019/12/malaysias-new-game-in-the-south-china-sea/

Porcaro, Giuseppe, García-Herrero, Alicia, and Guangzhao, Lyu. “China’s tales of the future.” Podcast audio August 2022 from ZhōngHuá Mundus by Bruegel.

Sexton, Renard. “Finding a Balanced China Policy: Constraints and Opportunities for Southeast Asian Leaders.” In Essays on China and U.S. Policy, edited by Lucas Myers, 501-519. Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, 2022.

Schuman, Michael. “China Could Soon Be the Dominant Military Power in Asia.” The Atlantic, May 4th, 2023. https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2023/05/china-military-size-power-asia-pacific/673933/

The White House. “ASEAN-U.S. Leaders’ Statement on the Establishment of the ASEAN-U.S. Comprehensive Strategic Partnership.” November 12th, 2022. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/11/12/asean-u-s-leaders-statement-on-the-establishment-of-the-asean-u-s-comprehensive-strategic-partnership/

United States Congress. “Taiwan Relations Act.” U.S. Government Information, April 10th, 1979. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-93/pdf/STATUTE-93-Pg14.pdf.

Universo Online. “Brasil exportará para China sem passar por dólar.” March 29th, 2023. https://noticias.uol.com.br/colunas/jamil-chade/2023/03/29/brasil-exportara-para-china-sem-passar-por-dolar.htm.

Valor International. “Agreements could increase use of renminbi in Brazil-China trade.” 14 febbraio 2023. https://valorinternational.globo.com/economy/news/2023/02/14/agreements-could-increase-use-of-renminbi-in-brazil-china-trade.ghtml.

Wren, Digby James. “NATO part of US ocean-front strategy.” China Daily, February 2nd, 2023. https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202302/02/WS63db2ee3a31057c47ebac8ea.html.

Xiangmiao, Chen. “’Four Sha’ rumors aiming to fool world contrary to development trend of SCS.” Global Times, January 24th, 2022. https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202201/1246779.shtml.

Xie, Tao. “Opinion: Is President Xi Jinping’s Chinese dream fantasy or reality?” CNN, March 14th, 2014. https://edition.cnn.com/2014/03/14/world/asia/chinese-dream-anniversary-xi-jinping-president.

Xinhua. “Full text: China’s Policies on Asia-Pacific Security Cooperation.” The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, January 11th, 2017. http://english.www.gov.cn/archive/white_paper/2017/01/11/content_281475539078636.htm.

Yuniar, Resty Woro. “Explainer | Indonesia’s land and maritime border disputes with Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam.” South China Morning Post, January 12th, 2022. https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/explained/article/3163035/indonesias-land-and-maritime-border-disputes-malaysia.

***

[1] On the matter, see also my paper “Global Governance: Is Asia’s Time Coming?” Geopolitica. Revistă de Geografie Politică, Geopolitică şi Geostrategie, no. 96-97 (4/2022): 49-70, Bucureşti: Top Form, https://www.geopolitic.ro/2023/02/global-governance-asias-time-coming/; and “Tehrān towards Beijing and Moscow: strategic alliances and overcoming divergences,” Geopolitica, no. 92-93 (1/2022), Bucureşti: Top Form, https://www.geopolitic.ro/2022/02/tehran-towards-beijing-moscow-strategic-alliances-overcoming-divergences/

[2] Dan Lamothe, “U.S. general warns troops that war with China is possible in two years,” The Washington Post, January 27th, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/2023/01/27/us-general-minihan-china-war-2025/

[3] Jean-François Fiorina, then the Deputy CEO of the Grenoble École de Management, reported it in French. Jean-François Fiorina, “Suite de mon recueil de phrases géopolitiques (aujourd’hui la Chine).” LinkedIn, April 26th, 2022.

[4] Giuseppe Porcaro, Alicia García-Herrero, and Lyu Guangzhao, “China’s tales of the future,” podcast audio August 2022 from ZhōngHuá Mundus by Bruegel, https://open.spotify.com/episode/5LefIkEP9dQHeNgUkf9RyM?si=59013b27ada74628&nd=1.

[5] Laure Mandeville and David P Goldman, “AT tells Le Figaro why China is winning the tech war,” Asia Times, December 14th, 2020, https://asiatimes.com/2020/12/at-tells-le-figaro-why-china-is-winning-the-tech-war/

[6] Tao Xie, “Opinion: Is President Xi Jinping’s Chinese dream fantasy or reality?” CNN, March 14th, 2014, https://edition.cnn.com/2014/03/14/world/asia/chinese-dream-anniversary-xi-jinping-president.

[7] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, “Xi Jinping Attends the CPC in Dialogue with World Political Parties High-level Meeting and Delivers a Keynote Speech,” March 16th, 2023, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/zxxx_662805/202303/t20230317_11043656.html.

[8] NATO / OTAN, “NATO 2022 Strategic Concept,” Par. Strategic Environment, p. 5, June 29th, 2022, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2022/6/pdf/290622-strategic-concept.pdf.

[9] Renard Sexton, “Finding a Balanced China Policy: Constraints and Opportunities for Southeast Asian Leaders,” in Essays on China and U.S. Policy, ed. Lucas Myers (Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, 2022), 501-519.

[10] China.org.cn. “A New Type of Security Partnership.” November 4th, 2021, http://www.china.org.cn/english/china_key_words/2021-11/04/content_77851554.html#:~:text=A%20New%20Type%20of%20Security%20Partnership%20The%20Eighth,governance%20responding%20to%20the%20development%20of%20the%20times.

[11] According to the Review of Maritime Transport 2021 by the U.N. Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Asian global maritime trade maintained a 41% share of total goods loaded and makes use of eight out of the top ten ports, which include five in China.

[12] He said: “We’re headed to a likely future of competing spheres of influence … You’ll have a more differentiated pattern of power and influence in the region in which there isn’t just one hegemon who can go anywhere they want and do whatever they want.” See Michael Schuman, “China Could Soon Be the Dominant Military Power in Asia,” The Atlantic, May 4th, 2023, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2023/05/china-military-size-power-asia-pacific/673933/

[13] Joseph R. Biden, Jr., “Interim National Security Strategic Guidance,” The White House, March 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/NSC-1v2.pdf, 7-8.

[14] Council of the European Union, “EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific,” April 16th, 2021, https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-7914-2021-INIT/en/pdf.

[15] Thomas Kohlmann, “Opinion: Germany makes long overdue economic pivot in Asia,” Deutsche Welle, November 19th, 2022, https://www.dw.com/en/opinion-germany-makes-long-overdue-economic-pivot-in-asia/a-63804530.

[16] United States Congress, “Taiwan Relations Act,” U.S. Government Information, April 10th, 1979, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-93/pdf/STATUTE-93-Pg14.pdf.

[17] Department of State, United States of America, “A Free and Open Indo-Pacific. Advancing a Shared Vision,” November 4th, 2019, https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Free-and-Open-Indo-Pacific-4Nov2019.pdf.

[18] Christopher K. Colley, “The Emerging Great Power Triangle: China, India and the United States in the Indian Ocean Region,” in Essays on the Rise of China and Its Implications, ed. Abraham M. Denmark and Lucas Myers (Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, 2021), 59-86.

[19] The White House, “ASEAN-U.S. Leaders’ Statement on the Establishment of the ASEAN-U.S. Comprehensive Strategic Partnership,” November 12th, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/11/12/asean-u-s-leaders-statement-on-the-establishment-of-the-asean-u-s-comprehensive-strategic-partnership/

[20] The Chinese newspaper Global Times, inspired by the official newspaper of the Communist Party of China, the People’s Daily, relates the levels of Chinese claim in the South China Sea as follows: “In general, China’s SCS claims include three levels: first, China has sovereignty over the islands in the South China Sea, including the Four Sha [four island groups in the SCS]. Second, according to the UNCLOS [U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea], China enjoys internal waters, territorial waters, a contiguous zone, an exclusive economic zone, and a continental shelf based on the four islands. Third, China has historical rights in the SCS.”

[21] Bill Hayton, “After 25 Years, There’s Still No South China Sea Code of Conduct,” Foreign Policy, July 21st, 2021, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/07/21/south-china-sea-code-of-conduct-asean/

[22] Digby James Wren, “NATO part of US ocean-front strategy,” China Daily, February 2nd, 2023, https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202302/02/WS63db2ee3a31057c47ebac8ea.html.

[23] Chen Xiangmiao, “’Four Sha’ rumors aiming to fool world contrary to development trend of SCS,” Global Times, January 24th, 2022, https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202201/1246779.shtml.

[24] Resty Woro Yuniar, “Explainer | Indonesia’s land and maritime border disputes with Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam,” South China Morning Post, January 12th, 2022, https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/explained/article/3163035/indonesias-land-and-maritime-border-disputes-malaysia; Nguyen Hong Thao, “Malaysia’s New Game in the South China Sea,” The Diplomat, December 21st, 2019, https://thediplomat.com/2019/12/malaysias-new-game-in-the-south-china-sea/

[25] International Monetary Fund, “World Economic Outlook Database,” April 2023, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2023/April.

[26] Xinhua, “Full text: China’s Policies on Asia-Pacific Security Cooperation,” The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, January 11th, 2017, http://english.www.gov.cn/archive/white_paper/2017/01/11/content_281475539078636.htm.

[27] Anis H. Bajrektarevic, “Unavoidability of Sino-American Rift: History of Strategic Decoup,” International Institute for Middle East and Balkan Studies (IFIMES), December 25th, 2021, https://mailchi.mp/753db3b52d87/analysis-prof-dr-anis-h-bajrektarevic-unavoidability-of-sino-american-rift-history-of-strategic-decoupling?e=9ba89dd268.

[28] The information sources of the news are: Valor International, February 14th, 2023, https://valorinternational.globo.com/economy/news/2023/02/14/agreements-could-increase-use-of-renminbi-in-brazil-china-trade.ghtml; Al Mayadeen, October 15th, 2022, https://english.almayadeen.net/news/economics/bank-indonesia-calls-against-payments-in-us-dollars; Geopolitical Report ISSN 2785-2598, no. 30 (4/2023), Rome, Italy: SpecialEurasia, https://www.specialeurasia.com/2023/04/13/saudi-arabia-us-dollar-yuan/; Cash Treasury Management File, June 23rd, 2022, https://ctmfile.com/story/brics-countries-keen-to-develop-own-payment-systems-industry-roundup-twenty-third-june; Universo Online, March 29th, 2023, https://noticias.uol.com.br/colunas/jamil-chade/2023/03/29/brasil-exportara-para-china-sem-passar-por-dolar.htm.