by Glauco D’Agostino

This article was first published in “Geopolitica. Revistă de Geografie Politică, Geopolitică şi Geostrategie”, Anul XV, nr. 70 (2 / 2017) “PROIECŢII GEOPOLITICE PE FALIA EURASIATICĂ“, Editura “Top Form”, Asociaţia de Geopolitica Ion Conea, Bucureşti, 2017. The author is a member of the International Scientific Board of the magazine

Iaşi (Romanian Moldavia), King Stephen III the Great’s Square, Palace of Culture (photo by the author)

Abstract

The USSR and Warsaw Pact breakup led to a new situation, with Romania and Bulgaria joining NATO and the EU, Ukraine and Georgia aspiring to, and Moldova urged by both European and Russian pressures. Meanwhile, a security barrier against NATO has emerged, with the establishment of secessionist independent states, such as Transdnestrija, Abkhazija and South Ossetia, and Crimea reverting to Russia. The other regional player is Turkey, which welcomes millions of Circassians and hundreds of thousands of Abkhazians. Today, Moscow fears the growing nationalism to a Circassian national entity within the Russian Federation. Even the Crimean Tatars trust in Turkish protection.

The most controversial issue in the whole Black Sea region concerns Bessarabia, a region belonging to Romania prior to 1944 and today politically divided between Moldova, Ukraine and Transdnestrija. The Kingdom of Romania was born in 1881 as a development of the Union of the Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, and in 1918 the Great Union of Romania was born. Then, in 1940 the establishment of Moldova as a USSR federal state until its 1991 independence. Today, Romania looks to Moldova with the eyes of ethnic homogeneity and its own historical configuration, and the shadow of Russian annexation of Transdnestrija weighs on Romanians, as they fear a progressive Russkij Mir entrapment, especially after the Crimean record. Then, there are supposed Russian interferences in the Moldovan Gagauzia, which doesn’t sympathise with the Romanian nationalism and itself eventual absorption into a Greater Romania. The counterbalance to Russia in Gagauzia would be Turkey.

Meanwhile, Chișinău rejects the proposals for a Moldovian “asymmetric federation” with Gagauzia and Transdnestrija, but its concerns resided in the Russian military presence in the breakaway state. A Moscow’s current tendency is to create a transmission chain of Russian power over the Black Sea, where Crimea is already part of the Federation territory, and the remnant is an informal complement. The other political axis, the western one, seems to be no longer working because of the changed geopolitical conditions. A new regional character has come on stage: it’s Turkey.

Keywords: Black Sea, Russia, Turkey, Moldova, Romania, Bessarabia, Gagauzia, Transdnestrija, Greater Romania, Russky Mir, Crimea, Ukraine, NATO.

Does the Black Sea unite or divide the peoples settled on its shores? Looking at the current situation, one would say that it divides them. The western shores of the Black Sea in Romania and Bulgaria don’t seem to have much contact with the northern ones in Ukraine and Russia, which in turn are not communicating with each other because of the ongoing war between the two former Soviet nations; the same goes for the Russian banks with the east coast of Georgia. In the latter case, the reason is Abkhazija, the Georgian autonomous region self-proclaimed independent republic in 1992, recognised by the Russian Federation in 2008, and the same year declared as Russian-occupied territory by Georgia.

The Black Sea theme [map to side by NormanEinstein] is, as always, a geopolitical issue, where national and territorial political controversies arise. The main players are the Russian Federation and the West, apart from the fact that while we know well what Russia is, we don’t know what the West is, whether a NATO-branded political-military alliance or a purely intellectual concept identifying itself in an alleged unified civilisation from homogeneous peoples. Except that Turkey, which is not equated to Western civilization, is a NATO member and today in good relations with Moscow; and the European Union, the light of liberal democratic thought, seems to distance itself from American radicalization and also seeks good relations with Moscow. In short, a real snorter of a problem!

Thus, the Black Sea rises in our time as a confrontation blueprint overlooking the interests of the peoples who have settled in; and geopolitics, with its vision too focused on the global economic scenario, not always seems to interpret their material and transcendental interests. With this argument, we intend to stress historical and spiritual aspects concerning the people’s customs and way of life, which are often neglected by the emphasis on the Nation-State concept (the State built on the ethnic concept) certainly does not help understanding events, especially those are currently evolving. This doesn’t mean the aspects of geopolitical and military alliances should be underestimated, on the contrary! But they are certainly not the only ones.

Just from this point of view, the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact breakup led to a new situation in the region, that today sees Romania and Bulgaria joining NATO and the European Union, Ukraine and Georgia aspiring to, and Moldova (already associated with the EU as the previous two States) urged by both EU and Russian pressures. In addition:

- Since last December 23rd, Moldova, after pro-European Nicolae Timofti, has opted for Socialist pro-Russian Igor’ Nikolaevič Dodon as President, who, however, will have to share institutional power until 2018 parliamentary elections with Prime Minister Pavel Filip, Vice-President of the pro-European Democratic Party;[1]

- Bulgaria continues to maintain particularly good relations with Moscow, especially following the election of President Rumen Georgiev Radev (an independent, but supported by the pro-Russian Socialist Party), although the pro-European party Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria won a relative majority of Parliament seats in last March legislative elections.

Meanwhile, Russian diplomacy has set up a security barrier against NATO promotional influence, provoking and supporting the establishment of independent secessionist states, such as Transdnestrija (from Moldova), Abkhazija and South Ossetia (from Georgia), and, most recently, regaining Crimea from Ukraine in 2014. The effects are certainly destabilising with respect to post-Cold War arrangements, and certainly, some efforts to strengthen regional cooperation have not been very successful:

Meanwhile, Russian diplomacy has set up a security barrier against NATO promotional influence, provoking and supporting the establishment of independent secessionist states, such as Transdnestrija (from Moldova), Abkhazija and South Ossetia (from Georgia), and, most recently, regaining Crimea from Ukraine in 2014. The effects are certainly destabilising with respect to post-Cold War arrangements, and certainly, some efforts to strengthen regional cooperation have not been very successful:

- The Organization of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation, established in 1992 by all seven coastal States, plus Albania, Greece, Armenia, Azerbaijan and (since 2004) Serbia, did not produce realistic proposals;[2]

- whilst a more recent Romanian initiative to strengthen the joint naval presence of Romania, Bulgaria and Turkey NATO countries on the Black Sea has failed for the opposition of the Sofia government.[3] On the other hand, the Atlantic Alliance’s apparent disengagement in the area is in line with President Trump’s invitation to Europe to a greater commitment to its defence, without relying on a ceaseless allies’ involvement in regional crises.

Turkey, a cultural and religious regional player

If this is the political-military framework with an expanding Russian influence, changing the perspective on a level of ethnolinguistic and cultural attractiveness, another regional player is certainly Turkey. The Gagauzis from Moldova and Budzhak, the Tatars from Crimea and Dobrudzha, the K’aračajs, Balkars and Nogais from Northern Caucasus, the Bulgarian Turks and the Crimean K’arajs (for a whole of more than 1.5 million people) are ethnically and linguistically Turkic. And Turkey is home to about 350,000 Bulgarian Turks,[4] 180,000 Tatars, 90,000 Nogais, 20,000 K’aračajs and 15,000 Gagauzis. From the point of view of religious affiliation, the aforementioned ethnic groups are Muslim, except Gagauzis, who are Orthodox Christians, and the K’arajs, who belong to a tiny religious sect of Judaism.[5] This means the appeal of Turkey as a Muslim country extends to religious aspects, involving in the area at least 1.3 million more people than those of Turkic origin, mainly distributed on the Russian-Georgian side of the Black Sea.

In this regard, it’s interesting the affair involving Abkhaz and Circassians, both of Caucasian ethnicity, but the former today are mostly Christian Orthodox, the latter are Muslims of the Ḥanafī theological school of law. Turkey welcomes more than three million Circassians[6] and hundreds of thousands of Abkhaz[7] as a result of the Russian-Circassian and Russian-Turkish wars of the nineteenth century. In addition, the Abkhaz Muslims, in the majority during the 1920s when Abkhazija enjoyed the status of the Soviet Socialist Republic, gradually became a minority compared to the Georgian population since in 1931 Stalin had downgraded it to an Autonomous Republic within the borders of Georgia. Today Moscow fears that Circassians and Muslim Abkhaz together can fuel the growing nationalism calling for a Circassian national entity within the Russian Federation, a project currently hindered by a dispersion of the Circassian population in Kabardino-Balkaria, Adygea and Karačaj-Circassia.[8] In this, Turkey, taking advantage of its great historical and commercial relations with the Republic of Abkhazija (although Ankara doesn’t officially recognise it), could play a propulsion role not welcomed by Moscow, but still less acceptable by Tbilisi, since it claims sovereignty over the secessionist republic. However, the Christian and pro-Western Georgia possibly prefers to maintain good relations with a Muslim NATO country, rather than a hostile Russia that uprooted a large part of its territory.

In this regard, it’s interesting the affair involving Abkhaz and Circassians, both of Caucasian ethnicity, but the former today are mostly Christian Orthodox, the latter are Muslims of the Ḥanafī theological school of law. Turkey welcomes more than three million Circassians[6] and hundreds of thousands of Abkhaz[7] as a result of the Russian-Circassian and Russian-Turkish wars of the nineteenth century. In addition, the Abkhaz Muslims, in the majority during the 1920s when Abkhazija enjoyed the status of the Soviet Socialist Republic, gradually became a minority compared to the Georgian population since in 1931 Stalin had downgraded it to an Autonomous Republic within the borders of Georgia. Today Moscow fears that Circassians and Muslim Abkhaz together can fuel the growing nationalism calling for a Circassian national entity within the Russian Federation, a project currently hindered by a dispersion of the Circassian population in Kabardino-Balkaria, Adygea and Karačaj-Circassia.[8] In this, Turkey, taking advantage of its great historical and commercial relations with the Republic of Abkhazija (although Ankara doesn’t officially recognise it), could play a propulsion role not welcomed by Moscow, but still less acceptable by Tbilisi, since it claims sovereignty over the secessionist republic. However, the Christian and pro-Western Georgia possibly prefers to maintain good relations with a Muslim NATO country, rather than a hostile Russia that uprooted a large part of its territory.

If we turn our gaze more to the west, even the Crimean Tatars trust in the Turkish protection, as far this can be done in the current geopolitical framework with Erdoğan pledging to mend relations with Putin. But there are clear signs of an exponential increase of Tatar diaspora organizations in Ankara and Istanbul. And just a month after Russia annexed Crimea, Erdoğan himself, then Prime Minister, stood out promising protection for Tatar communities, language and culture. The Tatars were the ethnic majority in Crimea before the Khanate would have snatched from the Ottoman Sultanate protection in 1774 and earlier than glorious history of over three centuries would have ended with the 1783 annexation to the Russian Empire. The 1853-56 Crimean War led their mass flight mainly to Anatolia and Dobrudzha. Immediately opposed to the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, they gave rise to the Crimean People’s Republic,[9] the first attempt in the Islamic world to create a secular state with the aim of establishing equal rights for all ethnic groups.

Then, the communist persecution, the Sürgünlik (the deportations to Siberia and Central Asia Stalin ordered in 1944)[10] and the “forgetfulness” of Khrushёv over the Tatars did the rest: the latter case occurred when he allowed millions of proscribed by Stalinist purges to come back to their lands, making an exception to Tatars and reducing them to the current number of 230,000, net of those who left Crimea to Ukraine after its annexation in 2014.[11] In short, Crimea has been right the heart of competition on the Black Sea between Islam and Christianity, then between Christianity and Communism, and finally between Christianity, Islam and the secular world, with all resulting political implications about conceptions of state and communities.

Bessarabia: an ethnic-linguistic and historical dilemma

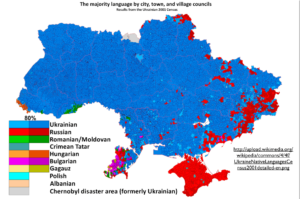

The most controversial issue in the whole Black Sea region, despite ethnic-religious and political problems presented above, concerns a particularly turbulent area from a historical and territorial point of view: Bessarabia, a region belonging to Romania before the Red Army occupied it in 1940 along with northern Bukovina and Hertza (today both in Ukraine). A 1930 census indicated the Bessarabian peoples were predominantly Romanian, with important Russian, Ukrainian, Jewish, and Bulgarian minorities [see map to side]. The National Council of Bessarabia, in the context of a potential Federal Russia after the October Revolution, had established the Moldavian Democratic Republic in late 1917 and had later voted for the unification with Romania at the beginning of 1918.[12] Even before, Bessarabia was born by the 1812 Treaty of Bucharest, when the Ottoman Sultanate had ceded the eastern part of the Principality of Moldavia to the Russian Empire at the end of the Russian-Turkish War and following a long series of temporary occupations by the Tsars. Today, Bessarabia is politically divided among Moldova, Ukraine and Transdnestrija, and therefore lives all the consequences of this political-territorial condition with pro-Western, pro-Russian and pro-Turkish influences.

In Bessarabia, among other ethnic minorities, the above mentioned Turkic and Christian-Orthodox Gagauzis live. Most of them are allocated in Gagauzia, the Autonomous Territorial Unit of Southern Moldova along the Ukrainian border, but about 25,000 of them live in the Budzhak historic region, in the Odessa oblast’. Following an outrush from Ottoman Bulgaria in the first half of the 19th century, today they are located at the border intersection of Romania, Moldova and Ukraine and not far from the southern border of Transdnestrija. The Gagauzis have for the most part over the last two hundred years faced Russian dominance, first by Tsars and then by Soviet Ukraine, while were suspended from a favourable policy and an opposed one of assimilation: for example, they received funding from Emperor Nicholas I to acquire the lands abandoned by Muslim Nogais in Bessarabia after the Treaty of Bucharest; but, when in 1848 they began a nationalist movement, the Cossacks harshly repressed them. It ended similarly when in 1905 they declared the Republic of Comrat (the current capital), and when two years later joined the Moldavians in an anti-Russian uprising.[13] After an association of Gagauzis to the Romanian and Moldavian affairs (respectively since 1918 and 1940), they declared independence in 1991, anticipating by eight days Moldova from the USSR.

In Bessarabia, among other ethnic minorities, the above mentioned Turkic and Christian-Orthodox Gagauzis live. Most of them are allocated in Gagauzia, the Autonomous Territorial Unit of Southern Moldova along the Ukrainian border, but about 25,000 of them live in the Budzhak historic region, in the Odessa oblast’. Following an outrush from Ottoman Bulgaria in the first half of the 19th century, today they are located at the border intersection of Romania, Moldova and Ukraine and not far from the southern border of Transdnestrija. The Gagauzis have for the most part over the last two hundred years faced Russian dominance, first by Tsars and then by Soviet Ukraine, while were suspended from a favourable policy and an opposed one of assimilation: for example, they received funding from Emperor Nicholas I to acquire the lands abandoned by Muslim Nogais in Bessarabia after the Treaty of Bucharest; but, when in 1848 they began a nationalist movement, the Cossacks harshly repressed them. It ended similarly when in 1905 they declared the Republic of Comrat (the current capital), and when two years later joined the Moldavians in an anti-Russian uprising.[13] After an association of Gagauzis to the Romanian and Moldavian affairs (respectively since 1918 and 1940), they declared independence in 1991, anticipating by eight days Moldova from the USSR.

In the present Republic of Moldova, most of the population self-identifies as Moldovan, but in the breakaway Moldovan Republic of Transdnestrija identification is equally tripartite among Moldovans, Russians and Ukrainians. However, whether Moldovans are a territorial variant of the Romanian ethnic group or to be regarded as a separate ethnic group remains controversial. This subject rebounds in linguistic terms on the State regulatory fundamentals, because, while the 1991 Declaration of Independence indicates Romanian as the official language of the State,[14] the existing 1994 Constitution states Moldovan is.[15] A decision by the Constitutional Court of 2013 settles the issue based on the principle that the Declaration of Independence has precedence over the Constitution. Indeed, it seems to be only a nominalistic politically motivated matter, as Moldovan seems to be just the name of Romanian spoken in Moldova during its membership in the Soviet Union.

In the present Republic of Moldova, most of the population self-identifies as Moldovan, but in the breakaway Moldovan Republic of Transdnestrija identification is equally tripartite among Moldovans, Russians and Ukrainians. However, whether Moldovans are a territorial variant of the Romanian ethnic group or to be regarded as a separate ethnic group remains controversial. This subject rebounds in linguistic terms on the State regulatory fundamentals, because, while the 1991 Declaration of Independence indicates Romanian as the official language of the State,[14] the existing 1994 Constitution states Moldovan is.[15] A decision by the Constitutional Court of 2013 settles the issue based on the principle that the Declaration of Independence has precedence over the Constitution. Indeed, it seems to be only a nominalistic politically motivated matter, as Moldovan seems to be just the name of Romanian spoken in Moldova during its membership in the Soviet Union.

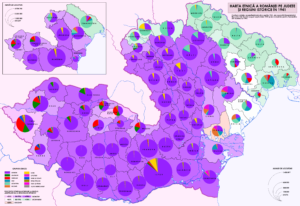

The ethnic map of Romania in 1941 at the level of the counties and the historical regions (by Andrein & Colinspancev)

During Romanian sovereignty over the entire Bessarabia before 1940, there was no ethnic and linguistic distinction between Romanians and Moldovans, all identified as Romanians (as noted in the 1930 census). However, Moldovans were called people from the Principality of Moldavia existing for more than five centuries; and today in Romania there is no lack of initiatives by Moldovan residents there towards the recognition of minority status, while all proposals have no success, despite support from the Republic of Moldova government authorities.

Disputes among Romania, Moldova and Ukraine

The Kingdom of Romania was born in 1881 as a development of the United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, which had been formed in 1859, formally settled three years later, and called Romania since 1866. Before Kingdom establishment, the Union of the Principalities was still under formal Ottoman sovereignty, though under a real Russian protectorate. At the end of the Russo-Turkish War, during which Romania sided with the Russians, the Peace of San-Stefano and the Treaty of Berlin were signed in 1878. The great powers agreed to the independence of Romania and the establishment of the Principality of Bulgaria, which however remained subordinate to Russian influence, though nominally a vassal of the Ottoman Sultanate. Bulgaria would have gained independence in 1908, while in 1918 the Alba Iulia Declaration would have given life to the Great Union of Romania, with the incorporation of Bessarabia (until then under Russian domination), Transylvania, Bukovina and the newly proclaimed Republic of Banat (all under the domination of defeated Austro-Hungarian Empire) to the Kingdom of Romania. The name of Moldavia, however, reappeared in 1924 within Soviet Ukraine as the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic,[16] composed of the present Transdnestrija and some territories of present-day Ukraine, that is, less than one-third of historical Moldavia. Then, in 1940 the creation of the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic as a federated state of the USSR,[17] a condition has lasted until it gained independence in 1991.

Now, all the aforementioned territories of the Kingdom of Romania were inhabited by a Romanian majority, with the exception of Bukovina which was populated in roughly equal parts by Ukrainians and Romanians. Next, the 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact would have resulted in the annexation to the USSR of the northern part of the region (mostly inhabited by Ukrainians) as a “minor reparation for the enormous loss inflicted on the Soviet Union and Bessarabia’s population by 22 years of Romanian reign over Bessarabia”. Today, Romanian Bukovina obviously has a majority of the Romanian population, but the controversy doesn’t stop because Ukrainian censuses continue to separate Romanians and Moldovans in Northern Bukovina, as well as at the national level.

The Romanian claims on Bessarabia represent a current political fact. In the author’s photo, writings on the Dâmboviţa River banks in Bucharest, August 2017

There is, therefore, a dispute by Romania over Moldova and Ukraine with regard to the recognition of the Romanian ethnicity, which Bucharest tends to extend to Moldovans. The above arguments have a significant political dimension in diplomatic and institutional relations among the countries of the area. Romania looks to Moldova with the eyes of ethnic homogeneity and its own historical configuration and could claim to intervene wherever the right of “Romanians” is questioned. On the Moldovan side, Mircea Ion Snegur, the first President since independence, declared in 1991: “Independence is of course a temporary condition. At first, there will be two Romanian states, but this will not last long. I repeat again that the independence of Soviet Moldova is a step, not an end”.[18] And Charles King, Professor of International Affairs at Georgetown University, wrote in 1994: “Moldovan should be no more than a regional identity in a reconstituted Greater Romania”.[19] While in 2009, pro-European Traian Băsescu, then President of Romania, reiterated the non-recognition of the borders with Moldova as “a consequence of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact”.[20]

The Romanian mistrust of Moscow expansionism and the Gagauzia case

The critics of these positions regard them as an extension of the 1918-40 “Greater Romania” pride to the present-day[21] and point out that Romania was the first country to recognize the new Republic of Moldova after its independence from the USSR.

Fullest extent of territory claimed by Novorossija, including the self-proclaimed People’s Republics of Donetsk and Lugansk

The right to defend the “Romanians” beyond the borders of Romania might also mean a clear response to the Kremlin theories about the right to defend the “Russians” wherever they are[22] (see the War in Donbas since 2014 and the resulting self-proclaimed People’s Republics of Donetsk and Lugansk).[23] It’s a purely geopolitical issue about opposition to Moscow’s expansionism and solidarity with Kiev, which overwhelms potential historical claims on the Budzhak region (still a shadow of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact). Also because the shadow of Russian annexation of Transdnestrija (which, by the way, has been the Moldavian area of longer Soviet membership, and its proclamation of independence continues to be supported by Moscow) weighs on the perception of Romanians, as they fear a progressive Russkij Mir entrapment, especially after the annexation of Crimea to the Ukraine damage; and the claim advanced by pro-Russian elements from Odessa for establishing Novorossija as a federal state within Ukraine[24] remembers too much the Imperial province of Russia that in the early 1900’s extended from Bessarabia to Donbas.

And then, supposed interferences from Russia on political issues in Gagauzia are lasting, yet:

- Specifically, those it exerted three years ago during the non-binding popular referendum, which revealed a preference for greater ties with Russia through the Eurasian Economic Union, the rejection of a Moldovan association with the European Union, and, indeed, the option of a Gagauzia independence in the event Moldova would reunite with Romania or become full EU or NATO member;[25]

- And a presumed pressure one year later, when the pro-Russian Irína Fëdorovna Vlah was elected as the Governor of the Autonomous Territorial Unit.

But it’s true a Russian influence on Gagauzis is historically remarkable, not only politically. Since 1991, the Gagauzis have used the modern Turkish alphabet, after having used the Cyrillic one since 1957, but still today the vast majority of people fluently speak Russian as a mother tongue alongside the local one, despite the official language of the state is Moldovan (or Romanian, as seen above).[26] Mikhail Formuzal, Irína Vlah’s predecessor, had this to say in 2008: “Our people are an integral part of the Russian World … and while it sounds paradoxical, knowledge of the Russian language is one guarantor of our self-preservation, including our ethnic identity”.[27]

Sure, the 160,000 Gagauzis from Moldova, culturally a mix of Turkish and Balkan morals, don’t sympathise with the Romanian nationalism and their eventual absorption into a Greater Romania, as they fear the autonomy currently have enjoyed since 1994 should be suppressed as was the case for the Hungarian Autonomous Regions in 1968.[28] Indeed, Comrat multiplies efforts for the Moldovan Parliament allowing a Tatarstan-style law on the language and local culture promotion. Doing so, it bothers pro-Romanians, who give to the proposal an alleged obvious intent to move away from the dominant culture in Chișinău. Paradoxically, Gagauzis find them as allies for the same goal of fighting the dominant Russian culture. Antinomies that are exactly the figure of a political situation in this area!

Nearby, more than 100,000 Moldovans and Gagauzis living in Budzhak seem not to suffer discrimination by the Ukrainians,[29] who are only 40% of the region’s population; especially the Gagauzis, given the favours they enjoy by law in terms of their language use and the incentives they receive to integrate into civil life. Rather, it’s precisely Ukrainians who have to worry about the growing pro-Russian feelings among other ethnic minorities.[30]

Many people hope the counterbalance to Russia in Gagauzia would be Turkey again, because of its already highlighted ethnolinguistic and cultural ties and its direct or vassalage Ottoman historical domain around almost all the Black Sea coastal arc. In fact, you can perceive a Turkish presence in the needy Moldovan autonomous territory through the economic aid provided by the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency, the government body responsible for assistance to countries with a low Human Development Index.[31] And this is what Gagauzia needs, opportunities to attract investments and financial resources.

Too bad for the Romanians the short-sighted European Union doesn’t realise Ankara’s active role in the area and continues to reject it, forcing it to a compromise with Moscow. “Defend me, Lord, from my friends”, titled a glorious Romanian daily.[32] On a Moldovan news portal in the Russian language, you can read: “The idea of Gagauzia as a bridge between Turkey and Russia has always been rather whimsical … what has prompted the two countries to turn to this strategy? Whether the vicissitudes of bilateral relations or something else, it is important today for Gagauzia to take full advantage of the opportunity”.[33] And there are those who, while acknowledging and appreciating this design represents a platform for developing cooperation between Russia and Turkey, admit that Turkish and Russian (or Russo-Turkish) interest for Gagauzia can hide a likely (alternative or joint) hegemonic design to win spheres of influence.[34]

Moldova: towards an “asymmetrical federation”?

Meanwhile, the Moldovan disputes between the Autonomous Territorial Unit of Gagauzia and the State appear to be getting stronger. The reason lies in different interpretations of the autonomy concept and its wording in the “Law on the Special Legal Status of Gagauzia”,[35] and, in this regard, the autonomous region contests above all that legal disputes are to be settled by the State Chancellery of Moldova.[36] Comrat charges Chișinău, among other things, the following penalties for its autonomy:

- An attempt to resize the Statute of Autonomy by a proliferation of national laws and government resolutions and orders that are incompatible with the Statute itself;[37]

- A strengthened control over territorial affairs in Gagauzia;

- The rejection of Gagauzia sovereignty proposals within the framework of a Confederation with Moldova and Transdnestrija.

The argument of a Confederation follows the same replica of the Moldovan Republic of Transdnestrija in response to the offer from the Republic of Moldova to establish a “self-administered territory” for the five districts beyond the Dnestr and the city of Tiraspol’, the capital of the secessionist state.[38] Some people remember that, despite the achieved status of independence, in 2003 Transdnestrija had agreed to the idea of a Moldovan “asymmetrical federation”, with common defence and currency (the Kozak Memorandum),[39] but then Moldovan President, the Communist Vladimir Nikolaevič Voronin, who had acquiesced at first, had rejected it in 2004 under pressure from the U.S., European Union and Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe.[40] Once again Chişinău’s concerns resided in the Russian military presence in the breakaway state so that in 2005 the Moldovan Parliament approved a measure to demilitarise and democratise the area as a prerequisite for any agreement. A Tiraspol’s response had come a year later, with another reaffirmation of its independence, yet, through a referendum with 97% approval.[41]

Traian Băsescu (left) and Nicolae Timofti, respectively former Presidents of Romania and Moldova, in the July 17th, 2013 meeting (Source: Președinția Moldovei)

However, diplomacy runs on other tracks. It was August last year when James Pettit, U.S. Ambassador to Moldova, said: “There is the issue of Transdnestrija, that is not even under central government control, but needs a special status which is an ultimate goal, but a special status within the Republic of Moldova”,[42] angering former Romanian President Traian Băsescu. Of course, the President in Chişinău was Timofti and Obama was sitting at the White House. But perhaps, if a Trump-Putin axis really exists, then today Moldovan Prime Minister Pavel Filip should worry!

Conclusion

Ghosts don’t end up shaking chains of claims. After all, history means something to the people, and not enough diplomatic assurances, military alliances and massive amounts of money to appease the ghosts of dependence and submission. Because too often peoples and ethnic groups have been subjected in the recent past to commands, attempts at assimilation and even deportations. The Crimean and Dobrudzha Tatars and the Gagauzis bear witness. But not only them.

The Black Sea problem lies in the consolidation of 19-20th-century nation-states, with a homogeneous population of different stories and, conversely, with countrymen too often separated by impermeable boundaries like impenetrable walls. For different reasons, Romania and Bulgaria have not yet overcome the WWII traumas, with the consequences of territorial mutilations or limited sovereignties. Moldova, Ukraine, Georgia and Russia itself seek a role that makes sense in the aftermath of the Soviet era. They swing among defending territorial unity, building new alliances and testing new expansionism while attending (some of them collusively, others impotently) the emergence of new state entities such as Transdnestrija, Abkhazija and South Ossetia, or self-sufficient rebelling regions such as Donetsk and Lugansk.

A fragmentation virus expands, overtly contrasting, on a historical level, the season of unifying Empires, such as the Ottoman’s (which at the end of the 16th century, along with its vassal states, controlled almost all Black Sea coastal countries) or the Russian’s (which, still in its Soviet version, had aggregated in terms of influence the northern arc of coastal countries). And worthless doctrinal references or temptations of siding “a priori” (a result of a now-gone ideological past), because grass-roots veracity proves far more complex than the simplified explanations suggested by respective government propaganda.

Russian Black Sea Fleet, 2X Nanuchka Class Guided Missile Corvettes (Source: http://foxtrotalpha.jalopnik.com/putins-game-of-battleship-the-black-sea-fleet-and-why-1537656215/1538692035)

Moscow’s current tendency to create a security barrier against NATO (which the Kremlin perceives as aggressive and arrogant towards it) seems to be undeniable. And it behaves so partly by soft diplomacy (a revealed harmony with Turkey and the U.S.), partly by a strategic destabilisation of significant areas. States looking at Putin with suspicion, even for legitimate concern over their full sovereignty and international viability, identify the route Chișinău-Tiraspol’-Comrat-Odessa-Sevastopol’-Simferopol’-Donetsk-Lugansk-Sukhumi-Tskhinvali as a long transmission chain of Russian power, where the central part of the run (Crimea, with its base of the Russian Black Sea Fleet) is already evidently and resolutely part of the Federation territory, and the remnant is an informal complement.

If this is true, the other route Sofia-Bucharest-Kiev-Tbilisi, the political axis detractors accuse of being at the service of the West, seems no longer working because of the changed geopolitical conditions. The West, while pledging to fight a more and more elusive “terrorist” enemy, crumbles as a concept and as a guarantor of territorial balances it was helping to shape for more than 70 years.

So what to do? A new regional character has come on stage, and, whether others like it or not, will play that role history has always assigned it: it’s Turkey. Maybe the other regional performers should make a virtue out of necessity. Putin’s Russia has already done so. The others, with due care and precautions, should recall the putative allies to their responsibilities, or, with required doubts and suspicions, should take note.

After all, this could be a forerunner of a new shared Black Sea structure based on the Russo-Turkish influence, as you had never seen in history!

[1] The cohabitation between the President and Prime Minister proves particularly difficult on foreign policy issues, where competence remains in the hands of the latter. Just in these days, there is another misunderstanding (or rather a divergence) between the two on the expulsion of five Russian diplomats from the Embassy in Chişinău ordered by Filip. See Moldova at impasse; President for Russia, Premier for Europe (June 2nd, 2017). Retrieved from http://www.fort-russ.com/2017/06/moldova-at-impasse-president-for-russia.html.

[2] Corina Rebegea (March 27th, 2017). The Black Sea As Battleground for Information Warfare: A View from Bucharest. Retrieved from http://www.eurasiareview.com/27032017-the-black-sea-as-battleground-for-information-warfare-a-view-from-bucharest/

[3] Bulgaria Rejects NATO Fleet in the Black Sea, Romania Hurriedly Backs Off (20.06.2016). Retrieved from https://sputniknews.com/world/201606191041590077-bulgaria-romania-nato-fleet/

[4] Ministry of Interior, General Directorate of Civil Registration and Nationality, Turkish Statistical Institute (06 July 2015). Place of Birth Statistics, 2014. Retrieved from http://www.turkstat.gov.tr/PreHaberBultenleri.do?id=21505.

[5] Mikhail Kizilov (April 9-12, 2003). Karaites and Karaism: Recent Developments, paper presented at the CESNUR 2003 Conference, Vilnius, Lithuania. Retrieved from CESNUR, Center for Studies on New Religions, http://www.cesnur.org/2003/vil2003_kizilov.htm.

[6] Kadir I. Natho (2009). Circassian History, Xlibris Corporation, USA, p. 505; and Sufian Zhemukhov (December 2008). Circassian World Responses to the New Challenges, in PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo, No. 54, p. 2.

[7] Amidst Ukraine Crisis, Turkey Courts Tatars, Abkhaz, and Gagauz in Soft-Power Campaign for Black Sea Dominance (May 18th, 2014). Retrieved from http://springtimeofnations.blogspot.it/2014/05/after-crimea-turkey-courts-tatars.html.

[8] Ibid.

[9] James B. Minahan (2000). One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups, Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut (USA), p. 189.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Updated Crimean Census Numbers (March 12nd, 2016). Retrieved from https://eurasianstudies.wordpress.com/2016/03/12/updated-crimean-census-numbers/

[12] Cristina Petrescu (2001). Contrasting/Conflicting Identities: Bessarabians, Romanians, Moldovans, in Nation-Building and Contested Identities: Romanian & Hungarian Case Studies, Regio Books (Budapest) Editura Polirom (Iaşi), p.156.

[13] Nikolas Kozloff (04/09/2017). Reflections on Ukraine, Russian Destabilization, Ethnic Separatism, the Gagauz People, a Voyage to Odessa and the So-Called “Bessarabian Republic”. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/reflections-on-ukraine-russian-destabilization-ethnic_us_58ea8f5ee4b0acd784ca599c.

[14] Presidency of the Republic of Moldova (n.d.). Declaration of Independence of the Republic of Moldova. Retrieved from http://www.presedinte.md/eng/declaration.

[15] Constitution of the Republic of Moldova, Title I General principles, art. 13 State Language, Use of Other Languages (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.constcourt.md/public/files/file/Actele%20Curtii/acte_en/MDA_Constitution_EN.pdf.

[16] Charles King (2000). The Moldovans: Romania, Russia, and the Politics of Culture, Hoover Institution Press, Stanford, California (USA), p. 52.

[17] Charles King (2000). The Moldovans, cit., pp. 93-94.

[18] John R. Haines (September 16th, 2016). Gagauzia: A Bone in the Throat. Retrieved from Foreign Policy Research Institute, http://www.fpri.org/article/2016/09/gagauzia-bone-throat-moldova/

[19] Charles King (June 1994). Moldovan Identity and the Politics of Pan-Romanianism, in Slavic Review, Volume 53, Issue 2, p. 345.

[20] John R. Haines (September 16th, 2016). Gagauzia: A Bone in the Throat, cit.

[21] Corina Rebegea (March 27th, 2017). The Black Sea As Battleground for Information Warfare, cit.

[22] Where and how Romania will fight Russia – Part I (2015/05/01). Retrieved from http://euromaidanpress.com/2015/05/01/where-and-how-romania-will-fight-russia-part-i/#arvlbdata.

[23] Howard Amos, Oksana Grytsenko and Shaun Walker (12 May 2014). Ukraine: pro-Russia separatists set for victory in eastern region referendum. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/may/11/eastern-ukraine-referendum-donetsk-luhansk.

[24] Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (21 April 2014). Latest from the Special Monitoring Mission to Ukraine – based on information received up until 20 April 2014, 20:00 (Kyiv time). Retrieved from http://www.osce.org/ukraine-smm/117881.

[25] Gagauz Autonomy Marks 20 Years of Pride and Prejudice (December 22nd, 2014). Retrieved from https://moldovanpolitics.com/tag/gagauz-referendum-2014/

[26] John R. Haines (September 16th, 2016). Gagauzia: A Bone in the Throat, cit.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Amidst Ukraine Crisis, Turkey Courts Tatars, Abkhaz, and Gagauz in Soft-Power Campaign for Black Sea Dominance (May 18th, 2014), cit.

[29] Nikolas Kozloff (04/09/2017). Reflections on Ukraine, Russian Destabilization, Ethnic Separatism, the Gagauz People, a Voyage to Odessa and the So-Called “Bessarabian Republic”, cit.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Amidst Ukraine Crisis, Turkey Courts Tatars, Abkhaz, and Gagauz in Soft-Power Campaign for Black Sea Dominance (May 18th, 2014), cit.

[32] Dan Dungaciu: „Apără-mă, Doamne, de prieteni“: Despre declaraţiile ambasadorului american la Chişinău în zece puncte (Dan Dungaciu: “Defend me, Lord, from my friends”: About the statements of the American Ambassador to Chişinău in ten points) (29 August 2016). Retrieved from http://adevarul.ro/international/europa/exclusiv-dan-dungaciu-apara-ma-doamne-prieteni-despre-declaratiile-ambasadorului-american-chisinau-zece-puncte-1_57c44c5b5ab6550cb832935c/index.html.

[33] Dmitrij Kara (4-07-2016). Русско-турецкое «потепление», как окно возможностей для Гагаузии: перспективы и риски (Russian-Turkish “warming” as a window of opportunities for Gagauzia: perspectives and risks). Retrieved from http://budjakonline.md/blogi/3284-russko-tureckoe-poteplenie-kak-okno-vozmozhnostey-dlya-gagauzii-perspektivy-i-riski.html.

[34] Vjacheslav Krachun (9 сентября 2015). Евразийская Гагаузия, как площадка для взаимодействия России и Турции (Eurasian Gagauzia, as a platform for cooperation between Russia and Turkey). Retrieved from https://regnum.ru/news/polit/1966341.html.

[35] Law on the Special Legal Status of Gagauzia (Gagauz-Yeri) (23.12.94), Nr.344-XIII, with amendments moved in accordance with Law No. 191-XV of 08.05.2003.

[36] John R. Haines (September 16th, 2016). Gagauzia: A Bone in the Throat, cit.

[37] Oleh Protsyk (2010). Gagauz autonomy in Moldova: the real and the virtual in post-Soviet state design, in Marc Weller and Katherine Nobbs, Asymmetric Autonomy and the Settlement of Ethnic Conflicts, Penn Press, Philadelphia.

[38] Charles King (June 1994). Moldovan Identity and the Politics of Pan-Romanianism, cit., p. 361.

[39] Officially, Russian Draft Memorandum on the Basic Principles of the State Structure of a United State in Moldova (17 November 2003). Retrieved from https://www.scribd.com/document/192677525/Kozak-Memorandum.

[40] John R. Haines (September 16th, 2016). Gagauzia: A Bone in the Throat, cit.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Ibid.

References

- Amidst Ukraine Crisis, Turkey Courts Tatars, Abkhaz, and Gagauz in Soft-Power Campaign for Black Sea Dominance (May 18th, 2014). Retrieved from http://springtimeofnations.blogspot.it/2014/05/after-crimea-turkey-courts-tatars.html.

- Amos, Howard, Grytsenko, Oksana and Walker, Shaun (12 May 2014). Ukraine: pro-Russia separatists set for victory in eastern region referendum. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/may/11/eastern-ukraine-referendum-donetsk-luhansk.

- Bulgaria Rejects NATO Fleet in the Black Sea, Romania Hurriedly Backs Off (20.06.2016). Retrieved from https://sputniknews.com/world/201606191041590077-bulgaria-romania-nato-fleet/

- Constitution of the Republic of Moldova, Title I General principles, art. 13 State Language, Use of Other Languages (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.constcourt.md/public/files/file/Actele%20Curtii/acte_en/MDA_Constitution_EN.pdf.

- Dan Dungaciu: „Apără-mă, Doamne, de prieteni“: Despre declaraţiile ambasadorului american la Chişinău în zece puncte (Dan Dungaciu: “Defend me, Lord, from my friends”: About the statements of the American Ambassador to Chişinău in ten points) (29 August 2016). Retrieved from http://adevarul.ro/international/europa/exclusiv-dan-dungaciu-apara-ma-doamne-prieteni-despre-declaratiile-ambasadorului-american-chisinau-zece-puncte-1_57c44c5b5ab6550cb832935c/index.html.

- Gagauz Autonomy Marks 20 Years of Pride and Prejudice (December 22nd, 2014). Retrieved from https://moldovanpolitics.com/tag/gagauz-referendum-2014/

- Haines, John R. (September 16th, 2016). Gagauzia: A Bone in the Throat. Retrieved from Foreign Policy Research Institute, http://www.fpri.org/article/2016/09/gagauzia-bone-throat-moldova/

- Kara, Dmitrij (4-07-2016). Русско-турецкое «потепление», как окно возможностей для Гагаузии: перспективы и риски (Russian-Turkish “warming” as a window of opportunities for Gagauzia: perspectives and risks). Retrieved from http://budjakonline.md/blogi/3284-russko-tureckoe-poteplenie-kak-okno-vozmozhnostey-dlya-gagauzii-perspektivy-i-riski.html.

- King, Charles (June 1994). Moldovan Identity and the Politics of Pan-Romanianism, in Slavic Review, Volume 53, Issue 2.

- King, Charles (2000). The Moldovans: Romania, Russia, and the Politics of Culture, Hoover Institution Press, Stanford, California (USA).

- Kizilov, Mikhail (April 9-12, 2003). Karaites and Karaism: Recent Developments, paper presented at the CESNUR 2003 Conference, Vilnius, Lithuania. Retrieved from CESNUR, Center for Studies on New Religions, http://www.cesnur.org/2003/vil2003_kizilov.htm.

- Kozloff, Nikolas (04/09/2017). Reflections on Ukraine, Russian Destabilization, Ethnic Separatism, the Gagauz People, a Voyage to Odessa and the So-Called “Bessarabian Republic”. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/reflections-on-ukraine-russian-destabilization-ethnic_us_58ea8f5ee4b0acd784ca599c.

- Krachun, Vjacheslav (9 сентября 2015). Евразийская Гагаузия, как площадка для взаимодействия России и Турции (Eurasian Gagauzia, as a platform for cooperation between Russia and Turkey). Retrieved from https://regnum.ru/news/polit/1966341.html.

- Law on the Special Legal Status of Gagauzia (Gagauz-Yeri) (23.12.94), Nr.344-XIII, with amendments moved in accordance with Law No. 191-XV of 08.05.2003.

- Minahan, James B. (2000). One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups, Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut (USA).

- Ministry of Interior, General Directorate of Civil Registration and Nationality, Turkish Statistical Institute (06 July 2015). Place of Birth Statistics, 2014. Retrieved from http://www.turkstat.gov.tr/PreHaberBultenleri.do?id=21505.

- Moldova at impasse; President for Russia, Premier for Europe (June 2nd, 2017). Retrieved from http://www.fort-russ.com/2017/06/moldova-at-impasse-president-for-russia.html

- Natho, Kadir I. (2009). Circassian History, Xlibris Corporation, USA.

- Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (21 April 2014). Latest from the Special Monitoring Mission to Ukraine – based on information received up until 20 April 2014, 20:00 (Kyiv time). Retrieved from http://www.osce.org/ukraine-smm/117881.

- Petrescu, Cristina (2001). Contrasting/Conflicting Identities: Bessarabians, Romanians, Moldovans, in Nation-Building and Contested Identities: Romanian & Hungarian Case Studies, Regio Books (Budapest) Editura Polirom (Iaşi).

- Presidency of the Republic of Moldova (n.d.). Declaration of Independence of the Republic of Moldova. Retrieved from http://www.presedinte.md/eng/declaration.

- Protsyk, Oleh (2010). Gagauz autonomy in Moldova: the real and the virtual in post-Soviet state design, in Marc Weller and Katherine Nobbs, Asymmetric Autonomy and the Settlement of Ethnic Conflicts, Penn Press, Philadelphia.

- Rebegea, Corina (March 27th, 2017). The Black Sea As Battleground for Information Warfare: A View from Bucharest. Retrieved from http://www.eurasiareview.com/27032017-the-black-sea-as-battleground-for-information-warfare-a-view-from-bucharest/

- Russian Draft Memorandum on the Basic Principles of the State Structure of a United State in Moldova (17 November 2003). Retrieved from https://www.scribd.com/document/192677525/Kozak-Memorandum.

- Updated Crimean Census Numbers (March 12nd, 2016). Retrieved from https://eurasianstudies.wordpress.com/2016/03/12/updated-crimean-census-numbers/

- Where and how Romania will fight Russia – Part I (2015/05/01). Retrieved from http://euromaidanpress.com/2015/05/01/where-and-how-romania-will-fight-russia-part-i/#arvlbdata.

- Zhemukhov, Sufian (December 2008). Circassian World Responses to the New Challenges, in PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo, No. 54.