by Glauco D’Agostino

This article was first published in “Geopolitica. Revistă de Geografie Politică, Geopolitică şi Geostrategie“, Anul XV, nr. 68-69 (1 / 2017) “CAUCAZ – RECONCILIERE ȘI RECONSTRUCȚIE“, Editura “Top Form”, Asociaţia de Geopolitica Ion Conea, Bucureşti, 2017.

Abstract

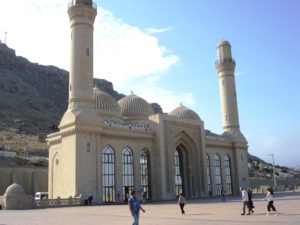

Among the three trans-Caucasian republics, Azerbaijan is currently the most challenging, due to its socio-economic, ethnic, religious and geopolitical features. Its internal problems remain dysfunctional institutions, corruption of the ruling political class, and a growing economic and social gap, which is leaving behind a widespread and grinding poverty over a tumultuous productive development anyhow the country boasts. There is a two-fold aspect of Azerbaijani identity: a Turkic ethnicity; and a membership in the Islamic community. Present Azerbaijan, following a long period of Soviet atheist ideology, is still a strongly secular state. Today’s several mosques are made subject to registration, religion remains excluded from school teaching, and the sale of all religious publications takes place under strict government control. Its secularism, however, did not prevent growth of Muslim feelings by people.

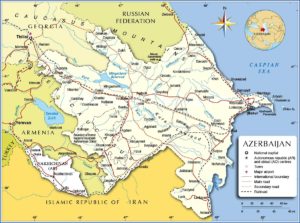

Azerbaijan is swinging between two strong regional influences, Sunni Turkey and Shiite Iran. The Turkish archetype allure evokes that pan-Turkism historically being opposed by Russia over its borders, but today worrying many governments that have achieved independence in the same area. On the other hand, the Azerbaijanis have a common cultural heritage with Iran. Another issue of new relevance worries Bakı rulers: a spillover by Salafist and Wahhābi groups into national boundaries. A thorn hurts the nation heart, as well: the situation of a geographically split territory (the Naxçıvan Autonomous Republic is isolated from the rest of the motherland) and a region, Nagorno-Karabakh, currently occupied by Armenian troops since the early ’90s, although Azerbaijani sovereign rights are recognised by the international community. The related Armenian-Azerbaijani War has also left a legacy of 26,000 deaths and one million refugees. Nagorno-Karabakh is the dominant theme because Azerbaijani territorial integrity is regarded as crucial to preserve national identity.

Keywords: Azerbaijan; Bakı; Nagorno-Karabakh; Artsakh; Naxçıvan; Islam; secularism; Shiism; Salafism; Wahhābism; Turkey; Iran.

Introduction

The Caucasus is the most sensitive Euro-Asian hinge from many points of view, from the geographical to political, economic, cultural and religious ones. All three trans-Caucasian states of Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan will form a most comprehensive compendium of it, epitomising a multi-identity complex, and acting as an East-West and Islam-Christianity bridge.

Among the three republics, Azerbaijan is currently the most challenging, due to its socio-economic, ethnic, religious and geopolitical features. We will devote our focus to this.

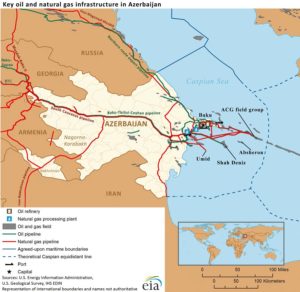

The country is in an oil-bound strong economic expansion [side map and photo 3 by the author] and Bakı is performing an urban and building restyling, making it worthy of admiration by many observers because of living standards you can reach there [photo 1 at the opening, 4, 5 and 6, all by the author, and photo 2 above]. However, its internal problems remain dysfunctional institutions, corruption of the ruling political class, and a growing economic and social gap, which is leaving behind a widespread and grinding poverty over a tumultuous productive development anyhow the country boasts. These findings are not so much different from the ones of the other Caucasian republics, where, according to the British writer Thomas de Waal, a nationalist caste of “modernizers and not reformers”, come to power after the 2003 Georgian Rose Revolution and consolidated also in the neighbouring countries as a model, doesn’t show any interest in institutional democratisation, and inhibits any activities emerging from the civil society.[1] So reforms remain a long-cherished dream.

The present standing shows a country with a Shiite-majority population (about 90%), suffering from Islamist insurrectional attempts by both Sunni and Shiite groups. Above all, a thorn hurts the institutions and civic life hearts, as well: the situation of a geographically split territory (the Naxçıvan Autonomous Republic is isolated from the rest of the motherland by an Armenian-ruled strip, the Syunik Province) and a region, Nagorno-Karabakh, currently occupied by Armenian troops since the early ’90s, although Azerbaijani sovereign rights are recognized by the international community.

Nagorno-Karabakh is 5% of Azerbaijani national territory, and the related Armenian-Azerbaijani War has also left a legacy of 26,000 deaths (mostly Azeris) and one million refugees (including more than 700,000 Azeris fleeing from the disputed mountainous region, the surrounding regions, and Armenia). In addition, the war, which is frozen since the 1994 Russia-brokered ceasefire, continues de facto up a standard of low intensity through acts of hostility that have escalated in recent years. Among the war events, enough to cite April 11th 2016 fighting in Nagorno-Karabakh, which left 64 killed on the field.[2] But it’s sufficient to refer to the Azerbaijani Defence Ministry figures in late 2015 when an impressive 105 cases of Armenian ceasefire break occurred in a single weekend;[3] and substantially the same figures are credited to the Azerbaijanis by the corresponding Armenian body.[4]

Nagorno-Karabakh is 5% of Azerbaijani national territory, and the related Armenian-Azerbaijani War has also left a legacy of 26,000 deaths (mostly Azeris) and one million refugees (including more than 700,000 Azeris fleeing from the disputed mountainous region, the surrounding regions, and Armenia). In addition, the war, which is frozen since the 1994 Russia-brokered ceasefire, continues de facto up a standard of low intensity through acts of hostility that have escalated in recent years. Among the war events, enough to cite April 11th 2016 fighting in Nagorno-Karabakh, which left 64 killed on the field.[2] But it’s sufficient to refer to the Azerbaijani Defence Ministry figures in late 2015 when an impressive 105 cases of Armenian ceasefire break occurred in a single weekend;[3] and substantially the same figures are credited to the Azerbaijanis by the corresponding Armenian body.[4]

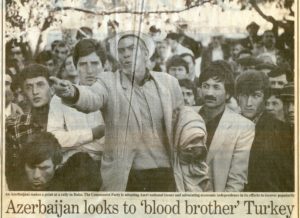

Photo 7 (by Hugh Pope) – On this article published before the USSR fall, a rally in Bakı looking to “blood brother” Turkey

Among the international stakeholders most sensitive to this problem, Turkey has repeatedly expressed concern about the Armenian occupation and raised protests over the UN and other international bodies’ inertia. As for last, Yalçın Topçu, Chief Advisor to President Erdoğan and the Great Unity Party nationalist leader from 2009 to 2011, visiting Bakı on November 21st last year, said: “Despite Khojaly massacre, more than 1 million refugees and internally displaced people, the international community is silent”. Emphasising the Turkic world as one family, he added that “Turkey and Azerbaijan are twin brothers” and “The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict is not only a problem of Azerbaijan but the entire Turkic and Islamic world”.[5]

A complex identity

So, Topçu’s speech stresses a two-fold aspect of Azerbaijani identity:

- A Turkic ethnicity, also marked by the Azeri language derived by south-western Turks’ Oğuz;

- And membership in the Islamic community.

The first Turkic tribes from Central-Eastern Asia settled in the Eastern Caucasus starting from V century A.D., even before the rise of Islamic civilisation; they embraced Islam after the Arab conquest two centuries later and didn’t become a majority in the local population before XI century when Seljuk Sultanate was established. Nevertheless, the Azeris have always had a primary consideration of their Islamic identity with respect to the ethnic one.[6] Shiism and Sufism reached this region at the time of the Shiite Buwaihid Emirate,[7] which ruled the Persian area over X-XI centuries as a protector of the Sunni Abbasid Caliphal dynasty. The Azeri-Kurdish Safavid dynasty, belonging to the homonymous Sufi brotherhood founded in Persia in the XIII century, overlapped Shiism as the State religion to the Sunni faith of most people of the area when it established its Empire in 1501.[8] Destructive Turkish-Persian wars followed, showing religious connotations of a Shiite-Sunni confrontation and involving the Azeri population as a whole.[9] After the XIX-century Russian conquest, the designation of Tatars (an ethnic word in itself) given to Azeris was still referring to the religious identity of the Empire Muslim peoples, and just in the late 1800s, a national consciousness started developing. A result was the awareness of an Azerbaijani people setting up, but also a successful uptake of traditional ethnic (e.g., stemming from nomadic lifestyle) and religious behaviours (arising from belonging to either the Shiite or Sunni community).[10]

When in May 1918 the Azerbaijani members of Parliament declared independence from the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic (founded to counter the October Revolution in Russia), Azerbaijan became the first Muslim republic of modern times. That dream was broken in April 1920, when the Republic of Azerbaijan was conquered by the Red Army and reconstituted as a Soviet republic. As a result, Muslim religious affairs were centralised in Ufa,[11] before in 1943 Soviets would move related competencies for Transcaucasia to Bakı, and manage it through the Muslim Spiritual Directorate, a Shiite-led body with a Sunni deputy.[12] In 1989 the latter was renamed Supreme Board of Muslims of the South Caucasus and, due to its delegitimizing after the USSR’s collapse,[13] since 1992 a Caucasus Muslim Board has been running with jurisdiction still from Bakı over Sunni Muftīs of Georgia, Chechnja, Dagestan, Ingushetija, Kabardino-Balkarija, Karačaj-Čerkesija and Ad’igeija, as well as over the Shiite communities of the former Soviet republics. Since 1993 there has been a High Religious Council of the Caucasian People,[14] yet, and since 2001 the State Committee for Work with Religious Organisations of the Republic of Azerbaijan, in charge of regulating the activities of religious organisations.[15]

Obviously, this plurality of actors entitled to basically similar functions often created a conflict of competence about religious authority tasks in the country, enabling a repressive interference by the Ministry of National Security in religious affairs, at least with regard to the radicalization of movements. As said earlier, this phenomenon is indeed increasing in recent years, and it causes apprehension to the authorities, also because it’s the first time some Shiite organizations are involved: for instance, on November 25th-26th, 2015, in a village of Abşeron Peninsula, close to Bakı, five “radical Islamists” of the Movement for Muslim Unity have been killed and 32 others have been arrested (including its leader Taleh Kamil oğlu Bağırov) over an alleged attempt to “change of the constitutional order” aimed to “the introduction of Sharī’a law in the country”. Actually, riots broke out just after the capture of the movement leader.[16] Perhaps, that should induce the government to consider repressive methods on political and religious groups designed to prevent conflicts not always lead to expected results in restoring order and peace.

Secularism, the revival of Islam, and post-Soviet political model

Present Azerbaijan, following a long period of Soviet atheist ideology, is still a strongly secular state, as ruled by the 1995 Constitution (amended in 2002): “Religion in the Azerbaijan Republic is separated from the state. All religions are equal before the law”.[17] Nevertheless, while in the mid-’80s only 16 mosques stood open for worship across the country and none of them in Nagorno-Karabakh,[18] today’s several mosques are anyway made subject to registration, religion remains excluded from school teaching, and sale of all religious publications takes place under strict government control. In addition, there are no government campaigns against alcohol and pork consumptions, and bearded men and women wearing a hijāb are very few.[19]

Azerbaijani secularism, however, did not prevent the growth of Muslim feelings by people, which more and more turn to faith as a response to the problems of their own existential condition. According to the Caucasus Research Resource Centers, a network of training and support to research established in 2003 in Tbilisi, Erevan and Bakı, the share of those who consider religion very important in their everyday lives had a significant rise in recent years, even though most of Azerbaijanis deem themselves as secular and act accordingly. Of course, attitudes vary with the age of the involved subjects, because it’s a physiological fact that the older generations (still bound to a Soviet lifestyle) are more prone to a laity-based behaviour, while new generations (41% of the population is under 25) are more open to a spiritual and symbolic appeal of religions.[20] This same phenomenon generally occurs in the former communist countries, but it’s exactly the opposite of what occurs in the so-called “Western” countries!

Then, the question is: What has enabled this revival of Islam in Azerbaijan after 70 years of Communist regime? The assumed answers reflect these concurring factors:

- Islam has been perceived as an element able of filling a lack of ideals left by the USSR collapse;[21]

- Islam has well represented a people’s need to recognise themselves in a historically achieved national identity, with its values and traditions;[22]

- Islam has played a role of people’s amalgam in addressing the issue of Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, and many of its Imām won by fighting a high reputation in the Azerbaijanis’ eyes;[23]

- Secularism, as the only relevant ideology in educational centres, has prompted a reaction, especially among young people, who are turning to Islam as a basis for salvation.[24]

The post-Soviet Azerbaijan and its people had soon looked at the West as a new model of inspiration. Quickly, a disenchantment by both institutions and people took the place of any expectations, especially due to a US attitude concerning aid to Azerbaijan:[25] on October 24th, 1992, the US Congress passed the Freedom for Russia and Emerging Eurasian Democracies and Open Markets Support Act (FREEDOM Support Act), from which, under Section 907 of the Act, Azerbaijan was ruled out “until the President determines (…) that the Government of Azerbaijan is taking demonstrable steps to cease all blockades and other offensive uses of force against Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh”.[26] Not even the provision, introduced in 2002, that the US can yearly waive it may ease the feeling of a boycott towards Azerbaijan, the only post-Soviet country to be excluded from providences. Furthermore, the US attitude about the conflict from the beginning was homolog to Russia’s, namely in favour of Armenia, and humanitarian relief was targeted towards the territory controlled by the separatist forces.[27]

Therefore, Nagorno-Karabakh represented the discriminating matter for identifying Azerbaijani friends and enemies, at least as long as the White House showed no interest in exploiting the oil fields in the Caspian Sea, but since with no change in its foreign policy choices on the Caucasian dossier. Economic interest, more than humanitarian values, many Azerbaijanis think, and nobody questions now the same logical leading to Western operations in Iraq has been imposing on them.

Photo 12 – President İlham Əliyev (Source: http://www.virtualkarabakh.az/read.php?lang=1&menu=5&id=5382#.WMcot9LhC70)

All that, along with a semi-authoritarian attitude of both Presidents Əliyev (father and son), who have followed one another since independence, has helped the birth of a radical Islam, mainly a Sunni-array one. Salafism is growing in Northern provinces bordering with the Russian Republic of Dagestan.[28] But the influence exerted over the past decades by religious preachers from abroad is likely to pour on Azerbaijan as a matter of international political nature.

Regional influences

Azerbaijan is swinging between two strong regional influences, Sunni Turkey and Shiite Iran, each of them taking steps to support their own religious beliefs by funding mosques, organisations and related activities.[29] On the other hand, precisely a secular and modernist lifestyle of a large portion of its population has prompted Azerbaijani governments to good relationships with the State of Israel since the early days after independence: “We share the same view of the world, I guess”, Michael Lotem, then Ambassador of Israel in Bakı and now Consul General in St. Petersburg, went to say in 2012. “We share quite a few common problems. For us Israelis to find a Muslim country which is so open, so friendly, so progressive, is not something the Israelis take for granted”, he added.[30] At the same period, Foreign Policy magazine reported the achievement of an Azerbaijani-Israeli agreement that would allow the use of Azerbaijani territory in case of Israeli attacks against Iran. Despite an obvious denial of both parties, it’s clear Iran constitutes an obsession for Azerbaijan. Just as it’s obvious that many Azerbaijanis, even among pro-Turkish Sunnis, don’t welcome alliances aimed to strike a Muslim country, particularly if these covenants are implemented with bitter enemies of Palestinian or Lebanese “brothers”.[31]

It’s a complex problem and certainly taking sides in international politics for an Azerbaijani citizen doesn’t assume the same approach followed in the West world. The Turkish archetype allure evokes that pan-Turkism historically being opposed by Russia over its borders, but today worrying many governments that have achieved independence in the same area. The Iranian issue is twofold, involving attraction and fear at the same time. The Azeri population is mostly Shiite and shares the same belief with Iran. From that comes the support Tehrān has given and still provides to various Azerbaijani Shiite groups, also utilising the fascination the Islamic Revolution exerts as a religious and social redemption tool. Iran allocated significant humanitarian aid to refugee camps from Nagorno-Karabakh through its Azerbaijani branches of Imām Khomeini Imdad Committee (which operated from 1993 to 2011) and of Iranian Ḥizb Allāhs.[32]

But Azerbaijan has a common cultural heritage with the bulky neighbour, which results from history. The Azeris lived under the Persian Empire until 1813, when, at the end of the Russo-Persian ten-years War, the Treaty of Gülüstan (a village not far from Nagorno-Karabakh) pursued an Azeri population partition between the Romanov’s Tsarist and the Qājār’s Persian Empires. By the subsequent Treaty of Türkmənçay in 1828, the Persian Khanates of Naxçıvan and Talış passed into Russian hands, as well.[33] Ever since, the Azeris live separated each other, as a result of a border that, even after Azerbaijan independence, has strengthened the difficulty of its crossing, due to mutual mistrust. This is easily explained:

- 15-25 million Azeris (depending on different estimates)[34] live nowadays in the Islamic Republic of Iran, which is 18-30% of the Iranian population as a whole. And these rates go up when considering those who originate from Azeri households or places, as just the name of Rahbar Khāmene’i (coming from a city of an Iranian Province of Eastern Azerbaijan) proves;[35]

- The Islamic Republic of Iran has covertly supported Armenia in the Nagorno-Karabakh crisis precisely because of its concerns of secession by Azeri-populated areas, alleged of pursuing the reunification to the Republic of Azerbaijan.[36] It’s also true that its initial neutrality and, in fact, mediating position during the conflict has never questioned Azerbaijan right to keep its territorial integrity, not even after the ceasefire. But no pressure was ever made by Tehrān to induce Erevan to become more reasonable, also so as not to annoy Moscow;[37]

- The Āyatollāhs wary of Azerbaijani foreign policy swings, however always pro-Turkish, and today apparently pro-Israel, as mentioned above.

Photo 14 (by the author) – Şəki-Qəbələ route, a woman at work in a village of refugees from Nagorno-Karabakh

Apart from the Shiite one of Iranian source, another issue of new relevance worries Bakı rulers: a spillover by Salafist and Wahhābi groups into national boundaries, mainly from Dagestan and Saudi Arabia. It’s not that their doctrines have charmed too much the strong sense of tradition permeating Azeri consciousness and behaviour,[38] but their option for Azerbaijani reasons in Nagorno-Karabakh, their very participation in the conflict (even though limited in time), and calls to the international Islamic community as a whole for an anti-Armenian jihād aroused interest and a number of adhesions from the population, even due to impossible answers from Russian and Western models. This effort has succeeded particularly among refugees from the occupied territories, who required and still require practical and moral relief to their status of displaced people, not just in terms of any comfort, but lacking by now of their very identity, as well.

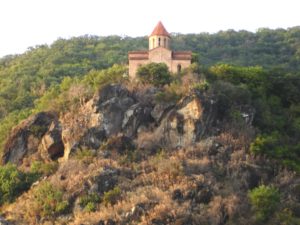

The Nagorno-Karabakh issue

As you can see, Nagorno-Karabakh is the dominant theme once again, because Azerbaijani territorial integrity is regarded as crucial to preserve national identity. According to current Armenian naming, the new political entity born by occupation is called Artsakh, a clear reminder to an Armenian kingdom that kept its independence until the XIII century during the settlement process of Turkic peoples in Transcaucasia. The name of Nagorno-Karabakh is an umpteenth compromise (this time of a linguistic nature) among Turkish, Persian and Russian culture, all of them being dominant in the XIX century: Karabakh, already existing in the XIII-century Georgian and Persian historical sources, is a fusion of respectively Turkish and Persian words kara (black) and bāgh (garden), while Nagorno is a Russian prefix translating the adjective mountainous. Karabakh identifies a mixed-populated region, whose highland is inhabited mainly by Armenians and the lowland mainly by Azeris.

The question of sovereignty over Nagorno-Karabakh arose during the First World War from both the 1917 implosion of the Tsarist Empire and the defeat of the Ottoman Sultanate. After efforts for acquiring Nagorno-Karabakh to their respective territory made by Turkey in 1918 and by newborn Democratic Republics of Armenia and Azerbaijan throughout their short life, under Bolshevik domain, both Soviet Socialist Republics of Armenia and Azerbaijan claimed sovereignty over the region. In 1921 a decision by the Stalin-led Narkomnats (People’s Commissariat of Nationalities) opposed the promises of the local Soviet leaders to assign Nagorno-Karabakh, Naxçıvan and Syunik to Armenia. Stalin, who was primarily looking at the events involving an almost-dying Ottoman Sultanate, ordered the assignment of the first two regions to Azerbaijan and the latter to Armenia. In 1923 the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast’ was born as an integral part of the Azerbaijan SSR and with Stepanakert as its capital city.[39]

The difficulties Soviet authorities had testified the complexity of the Nagorno-Karabakh affair, lasting to the present days. Difficulties of dealing with the related war under only one of the typical interpretative categories regulating the arrangement of an international dispute. Basically, strife may be regarded as:

- An ethnic conflict;

- A religious conflict;

- A territorial conflict.

Each of these categorizations implies different instruments of action for solving disputes. A problem arises when you were to agree that those three aspects contribute to finding their causes.

The interpretation of the conflict as a religious war is still the weakest argument, without denying interested boosts on either side designed to manipulate faith as a cultural heritage bulwark of their respective civilisations or to foment nationalist territorial appetites by making use of crusading pitches or, alternately, like those restricted to a jihād. The Republican Party of Armenia motto “Our strength is our faith”, uttered while using priests’ images, witnesses the need of nationalist political groups to lean on the Armenian Apostolic Church.[40] And we must remember precisely this ecclesial institution keeps alive among the Armenians a memory of what they call “the Armenian genocide” by the Turks (to whom the Azeris are ethnically assimilated) during the First World War. Similarly, Islam has had a revival in Azerbaijan as a result of the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, and the nationalist movements have taken advantage of that. But what is not acceptable is to swap consequences with causes.

The Azerbaijan-born journalist Shahla Sultanova supports the view that religion has been a key constituent factor for the birth of national identity: “I propose it is Islam that stayed at the core of new identities. Islam was successful as a core for people to gather around, and it became partly responsible for the formation of a new identity. Islamic activity seemed to have more success among the population, as its basic values are flexible for self-awareness and forming a national identity”.[41] And, according to Georgian Nino Chikovani, “Analysis of the role of religion in the Caucasian conflicts in the 1990s reveals the fact that religion did not play a leading role in these conflicts; it had a function of demarcation in cases when the opposed parties represented different religions. The conflicts led to strengthening the mutual distrust, but the conflicts resulted from the politicising of ethnicity and not from religion”.[42] These above-mention theories are not at odds with each other, since both claim more on the role of internal cohesion covered by Islam, rather than a contrast to external religious constituents.

The dispute over Nagorno-Karabakh reinvigorated after that in February-March 1986 Mikhail Gorbachёv, General Secretary of the Central Committee of the USSR Communist Party, announced at its 27th Congress a program of economic reforms, which quickly raised a demand for political reforms and triggered territorial claims among federated republics one against another. When in February 1988 the Artsakh Movement was born with the purpose of merging Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia, still under USSR authority, Gorbachёv, despite popular intentions were discordant, thought convenient to present the Azerbaijani-Armenian dispute as an ethnic and religious controversy to be able to better crush it by force. But he was also encouraged by Azerbaijani political circles, which aimed to involve alongside them countries such as Turkey, on one hand, and Iran, Saudi Arabia and Pakistan, on the other, all particularly sensitive to the value of ethnic or religious unity.[43] In fact, the Organization of the Islamic Conference was the first to take a stand against the Armenian occupation and for the restoration of international legality in Nagorno-Karabakh. However, a religious aspect never prevailed in the contenders’ attitude, but rather the ethnic aspect among the Armenians and the territorial aspect among the Azerbaijanis.

In July 1988 popular anti-Soviet and independence sentiments in Azerbaijan inspired the establishment of the Popular Front of Azerbaijan, an organisation with nationalist connotations to defend Nagorno-Karabakh. The extreme version of such feelings caused serious anti-Armenian massacres. Taking as a basis such episodes, but with a clear intent to crush an emerging political force with a major ability to aggregate and deemed to be dangerous for the Union cohesion, January 19th, 1990, Gorbachёv launched a military attack against Bakı, causing hundreds of victims and thereby permanently alienating the Azeri confidence.

After Azerbaijan gained independence from the USSR in October 1991, next December 10th in Nagorno-Karabakh and Azerbaijani Shaumjan district a referendum without the consent of the new Republic of Azerbaijan and boycotted by the Azeri population approved the independence of the region, followed January 6th, 1992, by the proclamation of the Republic of Artsakh (otherwise of Nagorno-Karabakh). Several UN Security Council resolutions condemned the secession as being contrary to international standards, thus confirming the belonging of Nagorno-Karabakh to Azerbaijan, but any ruling in this regard was turned down by separatist authorities.[44]

Not only that, but the slaughter of hundreds of Azeris in Khojaly on February 25th-26th, 1992, performed by militias from Armenia and Commonwealth of Independent States (at the time formed by Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan), and the Armenian capture of Şuşa (otherwise Shushi) next May 9th, followed by devastating looting, further soured the conflict. On June 16th, 1992, just on the wave of indignation and of a territorial integrity claim, Əbülfəz Elçibəy, a Naxçıvan-born former Soviet dissident and later Popular Front founder, was elected as President of the new republic, starting a policy on the restitution of mosques and church properties seized by the Soviets.

On June 24th, 1993, Heydər Əliyev, former Deputy Premier of the USSR and First Secretary of Communist Party of Azerbaijan in the period 1982-87, in his capacity as Chairman of the National Assembly gained by a few days, took the office of President of Azerbaijan in the absence of power following President Elçibəy’s removal. Practically, an exclusion from the highest office, since that time exerted by another Naxçıvan-born political leader, the same Əliyev who, as Chairman of the Supreme Soviet of Naxçıvan, in late 1991 had distanced himself not only from Moscow but also from Bakı. Against the backdrop, the 1992 military and diplomatic crisis involving Armenia, Turkey and Azerbaijan precisely on the Naxçivan exclave, which, it should be recalled, borders with Iran and Turkey, as well. The story was frozen right from Əliyev’s assumption of power in Bakı. President Əliyev inaugurated a dynastic power that, for better or worse, has been ruling Azerbaijan for 24 years.

Conclusion

Hard to bet on what the future of Azerbaijan will be because its geopolitical stance requires a tactical realism that often dulls long-term strategies. The Moscow-Ankara-Tehrān agreement on the Syrian issue is likely to spill out over the entire Middle East and the Caucasus region order, and this might affect the solutions to the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. That’s the point. Considering the Kremlin gives large protection to Erevan, will the newfound diplomatic harmony among the regional powers surrounding it successfully or unfavourably affect Azerbaijan territorial disputes with Armenia? And which working capacity will have any protection policies Turkey and Iran eventually wish to submit to a mediation board with the Russian Federation?

In this context and in the light of the new US withdrawal policy followed by Trump, even a request or expectation to cancel Section 907 of the FREEDOM Support Act (which prevents US economic aid) perhaps makes no sense. And the Minsk Group, working with no effectiveness within the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe to foster negotiations on Nagorno-Karabakh, is possibly outdated with regard to its running, as its Presidency is jointly assigned to the United States, Russia and France, even though there are some pending proposals for its integration with Turkey and Germany or the European Union.

This issue is not just about alliances or the historical legacy of their own cultures. Azerbaijan has a problem with the inner governance of institutions and on relationship with religious representation, primarily with the various Islamic faiths, even and especially in presence of a secular constitutional framework. In the former case, an efficiency enhancement and a moralization of the public apparatus, along with a resurgence of ethical principles in the civil society behaviour, take place through a proactive (and not merely repressive!) action to be activated in the law, security, civil liberties, education and social justice fields, towards recovery of a rapidly deteriorating social structure due to a tumultuous economic development. In the latter case, a secular model aseptically reproducing a refusal to recognize the religious role in the society (in line with the worst current practices of the Western world, or even worse, of the past Soviet world) would not help to patch up an awareness in the society of the historical role of the Azeri gens, and would ultimately meet standards of a mere national territoriality with no historical depth of identity. This all, of course, is in compliance with the religious freedoms granted by the Constitution.

We like to conclude with a quote exactly in this sense by a controversial figure, Heydər Əliyev himself, who, as a Shiite President but with the past tense of a top Communist leader, so stated, yet, at the International Symposium on “Islamic Civilization in the Caucasus” in 1998: “We, Azerbaijanis, being proud of Islamic religion, never treated negatively other religions, had no enmities with them, never intrigued and obliged other people to profess forcibly our religion. Generally, tolerance to other religions, living side by side with other religions under conditions of mutual understanding are peculiarities of Islamic values. During a stretch of history, it reflected itself in Azerbaijan and in the Caucasus as well. Christianity, the Judaism had existed and existing now in Azerbaijan along with Islamic religion since the oldest times”.[45]

It was yet more evidence, at the top level, that no religious legitimacy is given to the Azerbaijani-Armenian conflict.

[1] Hovhannes Hovhannisyan (July 23rd, 2016). Religion and religious Institutions in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict: does the religious factor play a role? Retrieved from Religions in Armenia, http://www.religions.am/eng/articles/religion-and-religious-institutions-in-the-nagorno-karabakh-conflict_–does-the-religious-factor-play-a-role/

[2] Fatima Tlisova and Mehdi Jedinia (April 11th, 2016). What’s Hiding Behind Russia’s Calls for Peace in Nagorno-Karabakh. Retrieved from http://www.voanews.com/a/russia-nagorno-karabakh-azerbaijan-armenia/3279945.html

[3] Armenia continues to violate ceasefire with Azerbaijan (December 6th, 2015). Retrieved from trend news agency, http://en.trend.az/azerbaijan/karabakh/2465804.html

[4] Azerbaijan uses mortars, grenade launchers in ceasefire violations (December 5th, 2015). Retrieved from http://www.panarmenian.net/eng/news/201788/Azerbaijan_uses_mortars_grenade_launchers_in_ceasefire_violations.

[5] Gunay Hasanova (November 21st, 2016). Official: Nagorno-Karabakh conflict is problem of entire Turkic, Islamic world. Retrieved from Azernews, http://www.azernews.az/karabakh/105401.html

[6] Caroline Cox and John Eibner (n.d.). Ethnic Cleansing in Progress: War in Nagorno Karabakh. Retrieved from Sumgait.info, http://sumgait.info/caroline-cox/ethnic-cleansing-in-progress/basic-facts.htm

[7] Islam in Azerbaijan (n.d.). Retrieved from Azerbaijan, http://www.azerbaijans.com/content_500_en.html

[8] Glauco D’Agostino (June 2010). Sulle Vie dell’Islam. Percorsi storici orientati tra dottrina, movimentismo politico-religioso e architetture sacre (Historical and Architectural Itineraries across the Muslim Countries), Gangemi, Rome, Italy, see p. 145.

[9] Hidayat Orudjev (2011). Background, Problems, and Prospects of Inter-Religious Dialogue in Azerbaijan, in World Religions in the Context of the Contemporary Culture: New Perspectives of Dialogue and Mutual Understanding, St. Petersburg Branch of the Russian Institute for Cultural Research, St. Petersburg, Part II, chapter 4, pp. 89 and 92.

[10] Caroline Cox and John Eibner (n.d.). Ethnic Cleansing in Progress, cit.

[11] Hidayat Orudjev (2011). Background, Problems, and Prospects of Inter-Religious Dialogue in Azerbaijan, cit., Part II, Chapter 4, p. 90.

[12] Paul Goble (July 9th, 2014). Window on Eurasia: A Sunni-Shiia Clash in Azerbaijan. Retrieved from Window on Eurasia – New Series, http://windowoneurasia2.blogspot.it/2014/07/window-on-eurasia-sunni-shiia-clash-in.html

[13] Zeyno Baran and Svante E. Cornell (2010). The Caucasus, in Barry Rubin, Guide to Islamist Movements, vol. 1, M.E. Sharpe, Armonk (New York)-London (England), p. 205.

[14] Alexander Agadjanian, Ansgar Jödicke and Evert van der Zweerde (n.d.). Religion, Nation and Democracy in the South Caucasus, Routledge, London (UK). Retrieved from https://books.google.it/books?id=JxbEBAAAQBAJ&pg=PT174&lpg=PT174&dq=Supreme+Board+of+Muslims+of+the+South+Caucasus&source=bl&ots=iRh8vAbANb&sig=CguyltPRwAQj5f7JK8O3F8S7uZc&hl=it&sa=X&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Supreme%20Board%20of%20Muslims%20of%20the%20South%20Caucasus&f=false.

[15] Svante E. Cornell (October 2006). The Politicization of Islam in Azerbaijan. Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program, Johns Hopkins University, Washington, D.C., pp. 64-66.

[16] Nurgul Novruz (November 30th, 2015). Deadly Clashes Between Police and Shia Muslims in Azerbaijan. Retrieved from Institute for War and Peace Reporting, https://iwpr.net/global-voices/deadly-clashes-between-police-and-shia-muslims.

[17] The Constitution of the Republic of Azerbaijan, Chapter II Basis of State, art. 18 Religion and state. Retrieved from http://en.president.az/azerbaijan/constitution.

[18] Caroline Cox and John Eibner (n.d.). Ethnic Cleansing in Progress, cit.

[19] Shahla Sultanova (August 15th, 2013). Azerbaijan: Islam Comes with a Secular Face. Retrieved from http://www.eurasianet.org/node/67396.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Shahla Sultanova (November 1st, 2011). National Identity, the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict and Revival of Islam in Azerbaijan. Retrieved from http://caucasusedition.net/analysis/national-identity-the-nagorno-karabakh-conflict-and-revival-of-islam-in-azerbaijan/

[22] Gunay Efendiyeva and Bakhtiyar Aliyev (2011). Interreligious Dialogue in the Context of Contemporary Culture: Islam, Christianity, and Other Religions in Azerbaijan, in World Religions in the Context of the Contemporary Culture, cit., Part III, Chapter 3, p. 176.

[23] Hovhannes Hovhannisyan (July 23rd, 2016). Religion and religious Institutions in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, cit.

[24] Svante E. Cornell (October 2006). The Politicization of Islam in Azerbaijan, cit. p. 10.

[25] Shahla Sultanova (November 1st, 2011). National Identity, the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict and Revival of Islam in Azerbaijan, cit.

[26] Section 907 of the Freedom Support Act (Public Law 102-511). Retrieved from http://karabakhfacts.com/section-907-of-the-freedom-support-act-public-law-102-511/

[27] Svante E. Cornell (October 2006). The Politicization of Islam in Azerbaijan, cit., p. 9.

[28] John J. Xenakis (December 7th, 2015). World View: Azerbaijan Faces Rising Radical Shia Islamist Insurgency. Retrieved from http://www.breitbart.com/national-security/2015/12/07/world-view-azerbaijan-faces-rising-radical-shia-islamist-insurgency/

[29] Paul Goble (July 9th, 2014). Window on Eurasia, cit.

[30] James Reynolds (August 12th, 2012). Why Azerbaijan is closer to Israel than Iran. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-19063885.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Shahla Sultanova (November 1st, 2011). National Identity, the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict and Revival of Islam in Azerbaijan, cit.

[33] Rashad A. Huseynov (2014). History and evolution of Islamic institutions in Azerbaijan (XIX-XXI centuries). Retrieved from Journal of Social, Political and Economic Studies, Volume 8, Issue 1-2 2014, https://www.academia.edu/9040323/History_and_evolution_of_Islamic_institutions_in_Azerbaijan_XIX-XXI_centuries_The_Caucasus_Globalization_Journal_of_Social_Political_and_Economic_Studies_Volume_8_issue_1-2_2014, pp. 1-2.

[34] Rasmus Christian Elling (February 2013). Minorities in Iran: Nationalism and Ethnicity after Khomeini, Palgrave Macmillan, New York (N.Y.).

[35] James Reynolds (August 12th, 2012). Why Azerbaijan is closer to Israel than Iran, cit.

[36] Shahla Sultanova (November 1st, 2011). National Identity, the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict and Revival of Islam in Azerbaijan, cit.

[37] Hovhannes Hovhannisyan (July 23rd, 2016). Religion and religious Institutions in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, cit.

[38] Shahla Sultanova (August 15th, 2013). Azerbaijan: Islam Comes with a Secular Face, cit.

[39] Caroline Cox and John Eibner (n.d.). Ethnic Cleansing in Progress, cit.

[40] Hovhannes Hovhannisyan (July 23rd, 2016). Religion and religious Institutions in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, cit.

[41] Shahla Sultanova (November 1st, 2011). National Identity, the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict and Revival of Islam in Azerbaijan, cit.

[42] Nino Chikovani (2011). Christianity and Islam in Modern Georgia: the Experience, Challenges, and Search for Responses, in World Religions in the Context of the Contemporary Culture, cit., chapter 6, p. 107.

[43] Hovhannes Hovhannisyan (July 23rd, 2016). Religion and religious Institutions in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, cit.

[44] Shahla Sultanova (November 1st, 2011). National Identity, the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict and Revival of Islam in Azerbaijan, cit.

[45] The speech of the President of the Azerbaijan Republic Heydar Aliyev at the international symposium on the topic “Islamic civilization in the Caucasus” (December 9th, 1998). Retrieved from “Heydar Aliyev Heritage” International Online Library, http://lib.aliyev-heritage.org/en/9045952.html

References

- Agadjanian, Alexander, Jödicke, Ansgar and van der Zweerde, Evert (n.d.). Religion, Nation and Democracy in the South Caucasus, Routledge, London (UK). Retrieved from https://books.google.it/books?id=JxbEBAAAQBAJ&pg=PT174&lpg=PT174&dq=Supreme+Board+of+Muslims+of+the+South+Caucasus&source=bl&ots=iRh8vAbANb&sig=CguyltPRwAQj5f7JK8O3F8S7uZc&hl=it&sa=X&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Supreme%20Board%20of%20Muslims%20of%20the%20South%20Caucasus&f=false.

- Armenia continues to violate ceasefire with Azerbaijan (December 6th, 2015). Retrieved from trend news agency, http://en.trend.az/azerbaijan/karabakh/2465804.html

- Azerbaijan uses mortars, grenade launchers in ceasefire violations (December 5th, 2015). Retrieved from http://www.panarmenian.net/eng/news/201788/Azerbaijan_uses_mortars_grenade_launchers_in_ceasefire_violations.

- Baran, Zeyno and Cornell, Svante E. (2010). The Caucasus, in Barry Rubin, Guide to Islamist Movements, vol. 1, M.E. Sharpe, Armonk (New York)-London (England).

- Chikovani, Nino (2011). Christianity and Islam in Modern Georgia: the Experience, Challenges, and Search for Responses, in World Religions in the Context of the Contemporary Culture: New Perspectives of Dialogue and Mutual Understanding, Petersburg Branch of the Russian Institute for Cultural Research, St. Petersburg.

- Cornell, Svante E. (October 2006). The Politicization of Islam in Azerbaijan. Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program, Johns Hopkins University, Washington, D.C.

- Cox, Caroline and Eibner, John (n.d.). Ethnic Cleansing in Progress: War in Nagorno Karabakh. Retrieved from info, http://sumgait.info/caroline-cox/ethnic-cleansing-in-progress/basic-facts.htm

- D’Agostino, Glauco (June 2010). Sulle Vie dell’Islam. Percorsi storici orientati tra dottrina, movimentismo politico-religioso e architetture sacre (Historical and Architectural Itineraries across the Muslim Countries), Gangemi, Rome, Italy.

- Efendiyeva, Gunay and Aliyev, Bakhtiyar (2011). Interreligious Dialogue in the Context of Contemporary Culture: Islam, Christianity, and Other Religions in Azerbaijan, in World Religions in the Context of the Contemporary Culture: New Perspectives of Dialogue and Mutual Understanding, Petersburg Branch of the Russian Institute for Cultural Research, St. Petersburg.

- Elling, Rasmus Christian (February 2013). Minorities in Iran: Nationalism and Ethnicity after Khomeini, Palgrave Macmillan, New York (N.Y.).

- Goble, Paul (July 9th, 2014). Window on Eurasia: A Sunni-Shiia Clash in Azerbaijan. Retrieved from Window on Eurasia – New Series, http://windowoneurasia2.blogspot.it/2014/07/window-on-eurasia-sunni-shiia-clash-in.html

- Hasanova, Gunay (November 21st, 2016). Official: Nagorno-Karabakh conflict is problem of entire Turkic, Islamic world. Retrieved from Azernews, http://www.azernews.az/karabakh/105401.html

- Hovhannisyan, Hovhannes (July 23rd, 2016). Religion and religious Institutions in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict: does the religious factor play a role? Retrieved from Religions in Armenia, http://www.religions.am/eng/articles/religion-and-religious-institutions-in-the-nagorno-karabakh-conflict_–does-the-religious-factor-play-a-role/

- Huseynov, Rashad A. (2014). History and evolution of Islamic institutions in Azerbaijan (XIX-XXI centuries). Retrieved from Journal of Social, Political and Economic Studies, Volume 8, Issue 1-2 2014, https://www.academia.edu/9040323/History_and_evolution_of_Islamic_institutions_in_Azerbaijan_XIX-XXI_centuries_The_Caucasus_Globalization_Journal_of_Social_Political_and_Economic_Studies_Volume_8_issue_1-2_2014.

- Islam in Azerbaijan (n.d.). Retrieved from Azerbaijan, http://www.azerbaijans.com/content_500_en.html

- Novruz, Nurgul (November 30th, 2015). Deadly Clashes Between Police and Shia Muslims in Azerbaijan. Retrieved from Institute for War and Peace Reporting, https://iwpr.net/global-voices/deadly-clashes-between-police-and-shia-muslims.

- Orudjev, Hidayat (2011). Background, Problems, and Prospects of Inter-Religious Dialogue in Azerbaijan, in World Religions in the Context of the Contemporary Culture: New Perspectives of Dialogue and Mutual Understanding, Petersburg Branch of the Russian Institute for Cultural Research, St. Petersburg.

- Reynolds, James (August 12th, 2012). Why Azerbaijan is closer to Israel than Iran. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-19063885.

- Section 907 of the Freedom Support Act (Public Law 102-511). Retrieved from http://karabakhfacts.com/section-907-of-the-freedom-support-act-public-law-102-511/

- Sultanova, Shahla (November 1st, 2011). National Identity, the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict and Revival of Islam in Azerbaijan. Retrieved from http://caucasusedition.net/analysis/national-identity-the-nagorno-karabakh-conflict-and-revival-of-islam-in-azerbaijan/

- Sultanova, Shahla (August 15th, 2013). Azerbaijan: Islam Comes with a Secular Face. Retrieved from http://www.eurasianet.org/node/67396.

- The Constitution of the Republic of Azerbaijan, Chapter II Basis of State, art. 18 Religion and state. Retrieved from http://en.president.az/azerbaijan/constitution.

- The speech of the President of the Azerbaijan Republic Heydar Aliyev at the international symposium on the topic “Islamic civilization in the Caucasus” (December 9th, 1998). Retrieved from “Heydar Aliyev Heritage” International Online Library, http://lib.aliyev-heritage.org/en/9045952.html

- Tlisova, Fatima and Jedinia, Mehdi (April 11th, 2016). What’s Hiding Behind Russia’s Calls for Peace in Nagorno-Karabakh. Retrieved from http://www.voanews.com/a/russia-nagorno-karabakh-azerbaijan-armenia/3279945.html

- Xenakis, John J. (December 7th, 2015). World View: Azerbaijan Faces Rising Radical Shia Islamist Insurgency. Retrieved from http://www.breitbart.com/national-security/2015/12/07/world-view-azerbaijan-faces-rising-radical-shia-islamist-insurgency/