by Glauco D’Agostino

This article was first published in “Geopolitica. Geopolitics, Political Geography and Geostrategy Magazine”, Year XIII, no. 59 (1 / 2015) “THE SAUDI RISING POWER – from Regional to International -“, Top Form Publishing House, Association of Geopolitics “Ion Conea”, Bucharest, 2015.

Summary. The soul of today Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, since its inception just over 80 years ago, has shared the contradictory aspects of tradition and modernity, always hanging between the ethical intransigence of Wahhābi costumes and the exogenous boost to an astounding technological progress, increasingly looking for a difficult coexistence of form and contents.

Summary. The soul of today Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, since its inception just over 80 years ago, has shared the contradictory aspects of tradition and modernity, always hanging between the ethical intransigence of Wahhābi costumes and the exogenous boost to an astounding technological progress, increasingly looking for a difficult coexistence of form and contents.

Saudi architecture cannot escape this seeming contradiction, because, in this specific context, functional aspects should not be irrespective of spiritual demonstration, which the Nation relies on, unlike the assumptions of secularized world; and because Islamic principles are supposed to represent a bridge to the standard distinction between religious and civil architecture, as well as for a cultural connection to the rest of Umma.

Taking for granted such assumptions, the actual adhesion of real action to ideal premises is not just recently questioned and is part of the ordinary debate between critics and experts of the SaudiKingdom.

There is a risk of weakening the very identity the traditional Islamic style portrays even today, and this claim points out an identification loss of different Peninsula regional styles depicting climatic and constitutive conditions of local areas. This as the use of reinforced concrete and introduction of air conditioning have progressively made useless any structural and compositive measures that have historically given form and function to usual both religious and civil buildings.

However, it’s not that this separation between modernity and tradition is proved to be so drastic, as efforts and attempts made by contemporary architects to reach a synthesis demonstrate.

Riyāḍ, with its current nearly six million inhabitants, has had ever growing urban developments. As for urban renewal, Makkah is the city showing the major strains of its historic fabric: much of the old city, made with unbaked mud brick, has been destroyed. Also Jeddah has widely renewed its urban fabric since the 50’s, and, as a result, a number of modern architectures have replaced many ancient historic buildings. Jeddah, however, is not free of Islamic-style new buildings. Madīnah, like Makkah with its Masjid al-Ḥarām, is inextricably connected with the presence of Masjid an-Nabawī, the Prophet’s Mosque. The architectural styles of Ḥijāz as a whole have absorbed the Ottoman political and cultural influence of Egypt, Syria, and Turkey since the XVI century. In FarasānIslands features of buildings have developed into a unique architecture typifying these islands. In terms of castles and palaces, Najrān southern Region exhibits the most significant and unique features in the Arabian Peninsula. In the EasternProvince you will find both Islamic vestiges and very modern universal-style housing and attempts to hybrid architecture.

Ultimately, Riyāḍ Diplomatic Quarter is an example of integration between Islamic tradition and technological development, a model for the Muslim Umma as a whole.

Glaring contrasts and efforts for synthesis

Anyone taking an overview of the Burj al Mamlakah (Kingdom Tower) project (photo 1, at the opening), the skyscraper will stand on the city of Jeddah to its completion within a few years, assume awareness of what Saudi Arabia has decided to become, by accepting the role (also symbolically) of Arab world economic-financial and architectural vanguard. Rating some 1,008 m. high and 167 floors, it will be the tallest building in the world, surpassing of 180 m. the Dubai City Burj Khalīfa (picture 2, right): an investment of US$ 1.23 billion, the first phase of a US$ 20 billion “KingdomCity” development, for a reinforced concrete and steel building with an all-glass façade.

Anyone taking an overview of the Burj al Mamlakah (Kingdom Tower) project (photo 1, at the opening), the skyscraper will stand on the city of Jeddah to its completion within a few years, assume awareness of what Saudi Arabia has decided to become, by accepting the role (also symbolically) of Arab world economic-financial and architectural vanguard. Rating some 1,008 m. high and 167 floors, it will be the tallest building in the world, surpassing of 180 m. the Dubai City Burj Khalīfa (picture 2, right): an investment of US$ 1.23 billion, the first phase of a US$ 20 billion “KingdomCity” development, for a reinforced concrete and steel building with an all-glass façade.

Anyone visiting Dumat al-Jundal ruined city, in al-Jawf northern region on the Jordanian border, and discovering the nearby Caliph ‘Umar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb Mosque (picture 3, left), will realize the Islamic tradition implicit in the history of Arabia and how it has produced a kind of architecture after all not unlike that of the neighboring Middle East’s. The Mosque establishment dates back to 638, that is, to the early Rāshidūn Caliphate, and, despite many alterations, it shows the typical features of Arabic religious architecture, that would have been used for many centuries:

Anyone visiting Dumat al-Jundal ruined city, in al-Jawf northern region on the Jordanian border, and discovering the nearby Caliph ‘Umar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb Mosque (picture 3, left), will realize the Islamic tradition implicit in the history of Arabia and how it has produced a kind of architecture after all not unlike that of the neighboring Middle East’s. The Mosque establishment dates back to 638, that is, to the early Rāshidūn Caliphate, and, despite many alterations, it shows the typical features of Arabic religious architecture, that would have been used for many centuries:

- A ṣaḥn (courtyard) preceding the main prayer hall, that is entered through a door situated in the qiblā wall (that one indicating the direction of prayer and prostration to Makkah);

- T functional scheme, distinctive of Arabic original style, with stone pillars running parallel to the qiblā wall and with wooden lintels;

- Prayer hall roof made of acacia and palm trunks;

- A rectangular minaret with pyramidal roof.

Some of these features, for instance, can be traced back to the original framework of coeval Amr ibn el-Ass Mosque of newborn Fustat (the original core of Cairo), which was established in 642 following the Egypt Arab conquest, still under the Caliphate of ‘Umar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb. Sure, initially Fustat Mosque had no minarets, and even less a pyramidal roof was so common at the time. But these few aforementioned features help to identify some of the architectural constants of religious buildings designed over the centuries in Arabia.

Therefore, the above two examples are extreme paradigms of the soul of today Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, which, since its inception just over 80 years ago, has shared the contradictory aspects of tradition and modernity, always hanging between the ethical intransigence of Wahhābi costumes and the exogenous boost to an astounding technological progress, increasingly looking for a difficult coexistence of form and contents.

Its architecture cannot escape this seeming contradiction, because, in this specific context, functional aspects should not be irrespective of spiritual demonstration, which the Nation relies on, unlike the assumptions of secularized world; and because Islamic principles are supposed to represent a bridge to the standard distinction between religious and civil architecture, as well as for a cultural connection to the rest of Umma. The Egyptian designer ‘Abdul-Wāḥed el-Wakil, a leading performer of Islamic architectural expression in Saudi Arabia, said: “One of the rare qualities I have in my work is that I’ve really studied sacred art and sacred architecture”.

Taking for granted such assumptions, the actual adhesion of real action to ideal premises is not just recently questioned and is part of the ordinary debate between critics and experts of the SaudiKingdom. “It’s amazing that the nobility and the knowledge once transmitted through sacred architecture today is lost. The cathedrals, the temples in Egypt, they all have a message to give. That is what I attempt in my work. And I do believe it is the lack of sacred attitude that’s causing so many problems today. I’m not talking about fanaticism, but something universal” el-Wakil still said, speaking about his choice for using local materials (earth and stone), also because of their durability and resistance to weather changes. As well because historical patterns testifying the use of stone in the Peninsula don’t lack: for example, the already mentioned Caliph ‘Umar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb Mosque; the early XIX-century Salwa Palace of ad-Dirʿiyya, the ruling center of as-Sa‘ūd’s family; Southern Ḥijāz and Farasān Islands historical architectures; Makkah, Jeddah and other coastal towns comfortable dwellings; the buildings of ʿAsīr southern region, including those ones of some areas where the façades are decorated with white quartz.

Of course, that claim emphasizes a risk of weakening the very identity the traditional Islamic style portrays even today, and points out an identification loss of different Peninsula regional styles depicting climatic and constitutive conditions of local areas. This as the use of reinforced concrete and introduction of air conditioning have progressively made useless any structural and compositive measures that have historically given form and function to usual both religious and civil buildings. And this diversification (religious, civil) makes little sense in architectural archetypes, when you think the mosque prototype is ultimately the Prophet’s house in Madīnah, which was a rudimentary hypostyle construction with various functions (including community gathering and prayer place) and providing an inner courtyard porch. In contrast, dwellings with the following features are now increasingly widespread:

- Large windows in external walls, with related problems of climate control, by now entrusted to a mechanized monitoring rather than the skillful use of natural techniques;

- Outside open gardens to replace the fenced yards, that offer more privacy and respect for neighbors’ rights, even and especially for women, given the context of country religious customs;

- A trend for compacting functions and architectural forms, earlier rationally distributed in separate spaces;

- An excessive use of external decorations (underlining social welfare), in contrast to sobriety of traditional house, all focused on internal livability.

However, it’s not that this separation between modernity and tradition is proved to be so drastic, as efforts and attempts made by contemporary architects to reach a synthesis demonstrate.

However, it’s not that this separation between modernity and tradition is proved to be so drastic, as efforts and attempts made by contemporary architects to reach a synthesis demonstrate.

- Traditional approaches for climatic conditioning, for instance, have been implemented to Jeddah Community Center and to the Corniche Mosques of the same city;

- Arches and colonnades are used in Jeddah International Medical Center;

- Mashrabiyas, the carved latticework screens protecting privacy and allowing fresh air to flow indoors, decorate northern and central Ḥijāz new buildings: the Elaf Taiba Hotel in Madīnah, again the Community Center and some of the Corniche Mosques in Jeddah;

- Qualitative techniques for lighting and ventilation have been adopted in Riyāḍ for the Ministry of Petroleum and Mineral Resources Building (picture 4, above), renovated in 1983, and for the United Nations Agencies office building, which has small triangular openings in the façade walls, Najdi traditional motifs already used in Riyāḍ Qaṣr al-Maṣmak of 1865 such as elements promoting continuous ventilation.

As for climatic conditioning and lighting, King Fahd Library Building in Riyāḍ (foreground in the picture 5, left) is worth mentioning, because of its innovative solutions envisaged in the design and concretized in its 2013 realization. First of all, the filigree steel cable structure of its façades (with changing-colours effects at night) provides protection from the sun, resulting in maximum light penetration and transparency, and meeting traditional Middle Eastern aptitude. The ancient Library building, including a dome (originally in concrete, now reconstructed in steel and glass), is embedded in the frame of a new structure as a whole, by enforcing monument preservation principles. By taking a very original solution, the new Library has a new roof, dotted with skylights, beneath which white membranes distribute the light throughout inner spaces. As a result, the symbolic cube-shaped King FahdLibraryBuilding, inclusive of exhibition areas, a bookshop and a restaurant, plays today the role of one of the most important cultural centres of the country, being part of the developing commercial and residential Olaya District.

As for climatic conditioning and lighting, King Fahd Library Building in Riyāḍ (foreground in the picture 5, left) is worth mentioning, because of its innovative solutions envisaged in the design and concretized in its 2013 realization. First of all, the filigree steel cable structure of its façades (with changing-colours effects at night) provides protection from the sun, resulting in maximum light penetration and transparency, and meeting traditional Middle Eastern aptitude. The ancient Library building, including a dome (originally in concrete, now reconstructed in steel and glass), is embedded in the frame of a new structure as a whole, by enforcing monument preservation principles. By taking a very original solution, the new Library has a new roof, dotted with skylights, beneath which white membranes distribute the light throughout inner spaces. As a result, the symbolic cube-shaped King FahdLibraryBuilding, inclusive of exhibition areas, a bookshop and a restaurant, plays today the role of one of the most important cultural centres of the country, being part of the developing commercial and residential Olaya District.

Riyāḍ, Konstantinos Doxiadis’ legacy and Najd

Riyāḍ (“The Gardens” is its meaning), since 1824 the Emirate of Najd capital (Second Saudi State) and since 1932 capital of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, with its current nearly six million inhabitants, has had ever growing urban developments, beginning with its royal residential district modernization in 1950 and the 60’s city grid pattern introduced by Konstantinos Doxiadis and his ekistics theory, previously put in place in Islāmābād, Pakistan. Over the last 40 years the city has played its most interesting cards of urban renewal on three action levels:

- The rehabilitation of historic districts, as it has been done since 1976 for Qaṣr al-Hokm district, an ongoing work, yet. Within district, this project has also involved the aforementioned Qaṣr al-Maṣmak and the reconstruction in 1992 of the Imām Turki bin ‘Abdullāh Grand Mosque (for 17,000 worshipers) by Jordanian architect Jamāl Rasem Badran;

- A revival of traditional Islamic architecture, as was the case of al-An Governor’s Palace rebuilding and Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency new head office, the latter having been designed with a traditional aesthetics, but with modern materials, methods, and functions;

- The development of “modernity” notion, by implementing major urban projects devoted to business and residence: King ‘Abdullāh Financial District is one of those ones, still now under construction, with 59 towers and 12,000 residents to be allocated, resulting in an investment of US$ 7.8 billion. The concept is to fully mainstream the most versatile Saudi people to Western standards. “But this integration stops at the district’s edge”, The New York Times roared in a 2010 article, acknowledging, however, that “the design guidelines say nothing about the separation of the sexes”.

But in fact, Riyāḍ has historically been part of the housing and cultural system of “upland” (“Najd” in Arabic, exactly) central region of Saudi Arabia, consisting of oases settlements within a semi-desertic Bedouins-inhabited landscape.

Let’s piece together the prevailing design themes in the ancient buildings of this region:

- unfired-brick or mud thick walls, ensuring load resistance and heat insulation performances;

- roofs built with tree stems and branches and plastered with mud;

- frequent presence of saw-tooth parapets and triangular relief decorations.

Even today, old traditional houses show the following construction features, although differences still remain between northern and southern parts of the region:

Northern Najd

- wide main doorways with rectangular or arched steps;

- lacking presence of outside portals;

- double access to larger homes: one for men and their male visitors, the other one for women;

- inner courtyard, where room doors and windows open in.

Southern Najd

- multi-storey buildings;

- courtyard surrounded by fodder storage chambers, warehouse for agricultural equipments, and the main staircase;

- upper floors for family rooms, a family elder special private chamber, kitchen, and services areas;

- a housework or gathering terrace, surrounded by a high wall, that is usually perforated to allow for air circulation.

Makkah and its relationship with al-Masjid al-Ḥarām

As for urban renewal, Makkah is the city showing the major strains of its historic fabric: much of the old city, made with unbaked mud brick, has been destroyed.

The determinant factor of its history is the presence of Masjid al-Ḥarām, the Sacred Mosque, the largest in the world, covering an area of 356,800 sq.m. (including indoor and outdoor prayer areas), and which may accommodate up to 4 million believers during Ḥājj. Its current basic layout dates back to 1577 (the age of Ottoman Sultan Selīm II), when the great Turkish Imperial architect Mi’mâr Sinân Âğâ, the Süleymaniye Mosque designer twenty years earlier, was commissioned to renovate the main Makkah mosque. Subsequent renovations were implemented in 1629, during the reign of Sultan Murād IV. But the turning point for the Mosque and the city itself was the decision of His Majesty King Sa‘ūd to proceed in 1955 to the first expansion of the Sacred Mosque in more than a thousand years, by increasing five-fold its area at the time, and replacing the seven short minarets with as many 89-meter other ones. At the same time, 300 m.-long aṣ–Ṣafā and al-Marwah Walk (bound to saʿy walking rite) (picture 6, above) was fully covered and included in the Masjid. Even more important than the previous one, has been the expansion King Fahd started in 1982 and should have completed six years later, the most impressive in the Mosque history. We won’t indulge in describing all the technological innovations introduced with these further works (air-conditioning plants, heat-resistant marble tiles on the floor, a drainage system, escalators, new sound systems). Nowadays, al-Masjid al-Ḥarām is once more expanding, by work started eight years ago and lasting up to 2020 at a cost of US$ 10.6 billion: by then, the whole area will have reached 40 hectares and the number of minarets will have been increased from the current 9 to a total of 11.

The determinant factor of its history is the presence of Masjid al-Ḥarām, the Sacred Mosque, the largest in the world, covering an area of 356,800 sq.m. (including indoor and outdoor prayer areas), and which may accommodate up to 4 million believers during Ḥājj. Its current basic layout dates back to 1577 (the age of Ottoman Sultan Selīm II), when the great Turkish Imperial architect Mi’mâr Sinân Âğâ, the Süleymaniye Mosque designer twenty years earlier, was commissioned to renovate the main Makkah mosque. Subsequent renovations were implemented in 1629, during the reign of Sultan Murād IV. But the turning point for the Mosque and the city itself was the decision of His Majesty King Sa‘ūd to proceed in 1955 to the first expansion of the Sacred Mosque in more than a thousand years, by increasing five-fold its area at the time, and replacing the seven short minarets with as many 89-meter other ones. At the same time, 300 m.-long aṣ–Ṣafā and al-Marwah Walk (bound to saʿy walking rite) (picture 6, above) was fully covered and included in the Masjid. Even more important than the previous one, has been the expansion King Fahd started in 1982 and should have completed six years later, the most impressive in the Mosque history. We won’t indulge in describing all the technological innovations introduced with these further works (air-conditioning plants, heat-resistant marble tiles on the floor, a drainage system, escalators, new sound systems). Nowadays, al-Masjid al-Ḥarām is once more expanding, by work started eight years ago and lasting up to 2020 at a cost of US$ 10.6 billion: by then, the whole area will have reached 40 hectares and the number of minarets will have been increased from the current 9 to a total of 11.

The Sacred Mosque presence has also affected Makkah urban development, by attracting substantial investment in its surrounding area. Examples of this are the Abraj al-Bayt Towers (picture 7, left), a post-modern-style project by the Lebanese Dar al-Handasah consulting organization, made with a steel / concrete composite structural system between 2004 and 2012 at a cost of US$ 15 billion. The highest of its towers, the Mecca Royal Hotel Clock Tower (picture 8, left), reaches 601 m. in height, has 120 floors, and encloses a large prayer room for more than 10,000 people, an Islamic Museum, a Lunar Observation Centre, and a clock with the world’s largest face. The dimensional, aesthetic, stylistic and functional contrast between al-Masjid al-Ḥarām and the Abraj al-Bayt Towers is yet another example of coexistence between traditional and modern architecture, although, as mentioned above, the Sacred Mosque does not retain much of the original structures, but still represents a symbolic element for the entire Muslim Umma. Unfortunately, the choice of Towers location has also resulted in the demolition of Ajyad Fortress Ottoman citadel, built in 1780, and in the leveling of the hill overhanging the Ka’ba site, where it stood.

The Sacred Mosque presence has also affected Makkah urban development, by attracting substantial investment in its surrounding area. Examples of this are the Abraj al-Bayt Towers (picture 7, left), a post-modern-style project by the Lebanese Dar al-Handasah consulting organization, made with a steel / concrete composite structural system between 2004 and 2012 at a cost of US$ 15 billion. The highest of its towers, the Mecca Royal Hotel Clock Tower (picture 8, left), reaches 601 m. in height, has 120 floors, and encloses a large prayer room for more than 10,000 people, an Islamic Museum, a Lunar Observation Centre, and a clock with the world’s largest face. The dimensional, aesthetic, stylistic and functional contrast between al-Masjid al-Ḥarām and the Abraj al-Bayt Towers is yet another example of coexistence between traditional and modern architecture, although, as mentioned above, the Sacred Mosque does not retain much of the original structures, but still represents a symbolic element for the entire Muslim Umma. Unfortunately, the choice of Towers location has also resulted in the demolition of Ajyad Fortress Ottoman citadel, built in 1780, and in the leveling of the hill overhanging the Ka’ba site, where it stood.

But the Abraj al-Bayt Towers are not the only striking case in point. Another Makkah settlement, the hybrid-style US$ 2.7 billion-cost Jabal Omar Development (pictures 9 and 10, right), a commercial and residential centre for 40,000 inhabitants started in 2008 and whose completion is scheduled by 2020, is being built in a land close to the Sacred Mosque.

But the Abraj al-Bayt Towers are not the only striking case in point. Another Makkah settlement, the hybrid-style US$ 2.7 billion-cost Jabal Omar Development (pictures 9 and 10, right), a commercial and residential centre for 40,000 inhabitants started in 2008 and whose completion is scheduled by 2020, is being built in a land close to the Sacred Mosque.

Jeddah, its architectural eclecticism and Wakil’s work

Also Jeddah, the coastal city by Ottoman and Egyptian influences, has widely renewed its urban fabric since the 50’s, and, as a result, a number of modern architectures have replaced many ancient historic buildings. Having become the stopover today welcoming most of the pilgrims from abroad aimed at Makkah, in 1981 it inaugurated the King ‘Abdul-’Azīz International Airport, at present among the world largest air terminals. Designed by well-known Bangladeshi-American structural engineer and architect Fazlur-Rahamān Khān, it stands out for the newfangled roof solution (that is composed of a series of tent-like canopies), for its universal-style Ḥājj Terminal (specially built in 1982 to handle pilgrims) and the King Fahd Royal Reception Pavilion (with traditional Islamic form). The National Commercial Bank HQ is of the same age. With its 27 floors torn by three high and profound openings on the façades, it’s marked by the subsequent three courtyards, which protect offices from direct sunlight, by resulting in further external controlled ventilation, in addition to the internal mechanized one.

Jeddah, however, is not free of Islamic-style new buildings, such as Dār adh-Dhikr al-Ḥākim School of 1994-95 and its 2004 extension. And even of the hybrid-style ones, as it’s the case of 1983-84 al-Andalus Elementary School and 2011 el-Khereiji Group Office Building.

In this regard, we cannot speak of revivalist architecture in Jeddah, without stressing the work of the aforementioned Egyptian architect ‘Abdul-Wāḥed el-Wakil, especially (but not only) in building mosques: these ones show all load-bearing baked-brick walls, and other traditional elements, such as vaults and domes, muqarnas, surfaces covered by white plaster or granite. Reinforced concrete is just used for foundations, lintels, and flat ceilings. Marble and granite are utilized for floors, walls, maḥārīb (the niches), and even minaret balconies.

The main his works in this city, all commissioned since 1979 to 1990 by the Ministry of Pilgrimage and Endowments, or the Municipality of Jeddah, or even by private citizens, are the following ones:

Mosques on the Corniche:

a) The Island Mosque (1986) is designed as a simple-shaped sculptural element in the landscape of an artificial island. A rectangular prayer hall, a porticoed ṣaḥn facing the sea, a square minaret, a dome on octagonal drum are included in its 400 sq.m. It does not contain separate areas for male and female;

b) The Sulayman Mosque (1980-88), a mixture of traditional Arab and contemporary styles, is externally austere. Its designer has taken care of re-introducing disused traditional Islamic elements, such as a central dome, an internal courtyard, the women’s prayer mezzanine;

c) The Corniche Mosque (1986-88) is a rural vernacular free-style 195 sq.m.-large architecture. It’s entered from the qiblā wall through a covered big room, a narthex and a riwaq (portico) overlooking the sea, towards the domed prayer chamber. It shows a thick octagonal minaret off and a catenary vaults;

d) The Moḥamed Farsi (Ruwais) Mosque (1989), a 216 sq.m.-large vernacular architecture, is a leading landmark because of three domes lining the qiblā wall.

Other mosques:

e) The Harithy Mosque (1986) is adorned by marble muqarnas in the two minarets balconies and in the miḥrāb, and by ceramic tiles from Kütahya, Western Turkey;

f) The Juffali Mosque (1986) is a vernacular old Jeddah-type mosque for 2,000 worshipers;

g) H.M. King Sa‘ūd Mosque (1987) (an īwān of its central court in the picture 11 on the left, by Zohair Harb), the largest one in Jeddah, is inspired by the Persian “four-īwān” scheme, particularly by the XVII-century Safavid-style Imām Mosque of Eşfahān. Its white monumental aspect is emphasized by the muqarnas-decorated entrance, imitating the huge portal of the Mamlūk-style Mosque-Madrasa of Sultan Badr-ad-Dīn al-Ḥasan in Cairo. On the other hand, the current mosque is the reconstruction of that Mamlūk and Moorish-style one built in the 1950’s. It encompasses a 5,000 sq.m. four-īwān rectangular prayer hall, the main large brick dome of 20 m span and rising 42 m, two undersized domes and a series of smaller ones, a 65 m. three-tiered minaret in brick masonry;

g) H.M. King Sa‘ūd Mosque (1987) (an īwān of its central court in the picture 11 on the left, by Zohair Harb), the largest one in Jeddah, is inspired by the Persian “four-īwān” scheme, particularly by the XVII-century Safavid-style Imām Mosque of Eşfahān. Its white monumental aspect is emphasized by the muqarnas-decorated entrance, imitating the huge portal of the Mamlūk-style Mosque-Madrasa of Sultan Badr-ad-Dīn al-Ḥasan in Cairo. On the other hand, the current mosque is the reconstruction of that Mamlūk and Moorish-style one built in the 1950’s. It encompasses a 5,000 sq.m. four-īwān rectangular prayer hall, the main large brick dome of 20 m span and rising 42 m, two undersized domes and a series of smaller ones, a 65 m. three-tiered minaret in brick masonry;

h) The ʿAzīziyyah Mosque (1988), 1,715 sq.m. for 1,000-2,000 worshipers, has a hypostyle plan (consisting of six aisles parallel to the qiblā wall), a small dome, and a graceful pencil-shaped minaret. It hosts residences for the imām and muezzin and teaching areas;

i) The Abraj (bin Lādin) Mosque (1988), 123 sq.m., retrieves Ottoman prototypes, specifically (except for its size) the XVI-century Sinân’s Princess Esmahan Mosque in Istanbul (better known as Sokollu Meḥmet Pasha Mosque). It has a rectangular domed prayer chamber, three domed bays, and a squared-base hexagonal pencil-minaret with a balcony supported by muqarnas vaults. It’s enriched by a marble miḥrāb.

Civil architectures:

j) The Sulayman Palace (1979) is a multi-storey coral and teak building, very well designed also for the rationality of intended uses (private areas, public areas, a guesthouse, a service wing);

k) The Jeddah Light (1990) (picture 12, right) is a 113 m.-high concrete and steel lighthouse, with a cylindrical shape, and carrying a spheroid globe.

k) The Jeddah Light (1990) (picture 12, right) is a 113 m.-high concrete and steel lighthouse, with a cylindrical shape, and carrying a spheroid globe.

Madīnah “the Radiant”, its ancient mosques and Masjid an-Nabawī

The cities of Saudi Arabia where Wakil has stood out for his works are also Madīnah and Makkah. In the latter city, Hafayer Mosque, close to Masjid al-Ḥarām, was completed in 2008. In Madīnah, three mosques he rebuilt are relevant:

a) Masjid Quba’ (picture 13, left) is the oldest mosque in the world. Built of palm logs and bricks by the Prophet Muḥammad in 622, then expanded in 684, renovated and enlarged in 706, again renovated in 1160 and several more times during Ottoman rule, its latest reconstruction in 1986 has followed the traditional local style: a rectangular prayer hall is topped with six large domes and is served by four minarets with decorated octagonal shafts; its ṣaḥn is covered by a retractable tent-like;

a) Masjid Quba’ (picture 13, left) is the oldest mosque in the world. Built of palm logs and bricks by the Prophet Muḥammad in 622, then expanded in 684, renovated and enlarged in 706, again renovated in 1160 and several more times during Ottoman rule, its latest reconstruction in 1986 has followed the traditional local style: a rectangular prayer hall is topped with six large domes and is served by four minarets with decorated octagonal shafts; its ṣaḥn is covered by a retractable tent-like;

b) Masjid al-Qiblatain (the Mosque of the Two Qiblās) (picture 14, right) was founded in 623 and is linked to the change of prayer direction from Jerusalem to Makkah that Archangel Gabriel ordered the Prophet. In the 1960’s this mosque was looking like a vernacular architecture of the Southern Arabian Peninsula, and it maintained a raised flat miḥrāb on the Jerusalem qiblā. Its 1992 reconstruction provides enough spaces for 2,000 worshipers. It shows a dome and a false dome, linked by small cross vaults in the Makkah direction, as well as two twin minarets. The main symmetric prayer hall is stressed by barrel-vaults running parallel to the qiblā wall;

b) Masjid al-Qiblatain (the Mosque of the Two Qiblās) (picture 14, right) was founded in 623 and is linked to the change of prayer direction from Jerusalem to Makkah that Archangel Gabriel ordered the Prophet. In the 1960’s this mosque was looking like a vernacular architecture of the Southern Arabian Peninsula, and it maintained a raised flat miḥrāb on the Jerusalem qiblā. Its 1992 reconstruction provides enough spaces for 2,000 worshipers. It shows a dome and a false dome, linked by small cross vaults in the Makkah direction, as well as two twin minarets. The main symmetric prayer hall is stressed by barrel-vaults running parallel to the qiblā wall;

c) Jama Masjid has been rebuilt where it’s believed the first Friday prayers were conducted.

Mīqāt al-Madīnah Mosque Complex, instead, was born by the draft for 5,000 worshipers Wakil made in 1987, with the function to receive and provide services to those who make the pilgrimage to Madīnah.

Despite the historical legacy of ṣafīḥa (Charter of Madīnah), attesting the Umma birth and the first political organization of Muslim people, the fate of Madīnah al-Munawwarah (“the Radiant City”) is, like Makkah, inextricably connected with the presence of a site cloaked in sacredness: it’s Masjid an-Nabawī, the Prophet’s Mosque (picture 15, right), the second holiest place in the world after Masjid al-Ḥarām. And, as the latter mosque, it has had a continuous expansion and an incredible aesthetic and technological transformation.

Despite the historical legacy of ṣafīḥa (Charter of Madīnah), attesting the Umma birth and the first political organization of Muslim people, the fate of Madīnah al-Munawwarah (“the Radiant City”) is, like Makkah, inextricably connected with the presence of a site cloaked in sacredness: it’s Masjid an-Nabawī, the Prophet’s Mosque (picture 15, right), the second holiest place in the world after Masjid al-Ḥarām. And, as the latter mosque, it has had a continuous expansion and an incredible aesthetic and technological transformation.

Over the VII-VIII centuries, Caliphs ‘Umar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb, ‘Uthmān ibn ‘Affān e al-Walīd I (whose latter name is tied to the creation of the first miḥrāb) one by one dealt with its enlargement; then, the Abbasids did repeatedly the same, and the Egyptian Mamlūks were responsible for building the dome (now green-coloured since 1839) above the Prophet’s tomb. The Ottomans proceeded to a further enlargement under the Sultanate of ‘Abdü’l-Mecīd-i I in 1849 (a XIX century Mosque depiction in the picture 16 on the right, used by BishkekRocks). By Kingdom of Saudi Arabia establishment, and since the early 1950’s, Sovereigns ‘Abd al-’Azīz, Faiṣal and Khālid produced significant changes and extensions to its area and to the mosque buildings, which were equipped with air-conditioning systems by King Faiṣal. In turn, King Fahd initiated the biggest expansion in this mosque history, making it “equal [to] the area of the city of Madīnah in ancient times”, quoting his own words; but, he did it even implementing cutting-edge technological arrangements, such as twenty seven moving steel domes in the new roofs, or the giant umbrellas opening automatically for shading courtyards (picture 17 above, by Sekretärin); and yet, service and transport tunnels and parking garages have been built underground. Today Masjid an-Nabawī counts ten 105 m.-high minarets and can accommodate 600,000 worshipers (increasing to 1 million during the Ḥājj period).

Over the VII-VIII centuries, Caliphs ‘Umar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb, ‘Uthmān ibn ‘Affān e al-Walīd I (whose latter name is tied to the creation of the first miḥrāb) one by one dealt with its enlargement; then, the Abbasids did repeatedly the same, and the Egyptian Mamlūks were responsible for building the dome (now green-coloured since 1839) above the Prophet’s tomb. The Ottomans proceeded to a further enlargement under the Sultanate of ‘Abdü’l-Mecīd-i I in 1849 (a XIX century Mosque depiction in the picture 16 on the right, used by BishkekRocks). By Kingdom of Saudi Arabia establishment, and since the early 1950’s, Sovereigns ‘Abd al-’Azīz, Faiṣal and Khālid produced significant changes and extensions to its area and to the mosque buildings, which were equipped with air-conditioning systems by King Faiṣal. In turn, King Fahd initiated the biggest expansion in this mosque history, making it “equal [to] the area of the city of Madīnah in ancient times”, quoting his own words; but, he did it even implementing cutting-edge technological arrangements, such as twenty seven moving steel domes in the new roofs, or the giant umbrellas opening automatically for shading courtyards (picture 17 above, by Sekretärin); and yet, service and transport tunnels and parking garages have been built underground. Today Masjid an-Nabawī counts ten 105 m.-high minarets and can accommodate 600,000 worshipers (increasing to 1 million during the Ḥājj period).

Ḥijāz stylistic influences, its towers, its castles

Makkah, Jeddah and Madīnah, the three cities mentioned above (plus the mountain city of Ṭā’if, in the Makkah Region), are all part of the large western geographic region of Ḥijāz, which, due to its geographic location, has absorbed the Ottoman political and cultural influence of Egypt, Syria, and Turkey since the XVI century, and, consequently, the architectural styles from time to time prevailing in these lands of the same Caliphate are the matrix of similarities you may meet in the region buildings. Obviously, this is even more true for the northern and central parts of Ḥijāz, while in Southern Tihāmah (the Red Sea coastal plain) most of old dwellings are similar in construction to the huts found on the nearby eastern coast of Africa; and in the remnant southern parts, less uniform features are applied, because of climate and economic factors.

As already done for Najd, we highlight the architectural features of traditional buildings:

Northern and Central Ḥijāz

- two to four-storey buildings;

- access from an arched doorway;

- external walls plastered with white or blue-coloured lime;

- multi-floor mashrabiyas, decorating doors, windows and the main façades of larger buildings, with water jars hung behind the wooden screens.

Southern Ḥijāz

- stone buildings;

- mud-plastered outer and inner walls;

- in some areas, painted designs (mostly created by women) on walls and stairwells;

- abundance of fortified structures, such as forts (with rectangular plans) and watchtowers (with circular bases), built in towns, open plains and valleys, on hills and mountaintops, because of foreign invasions and regional turmoil.

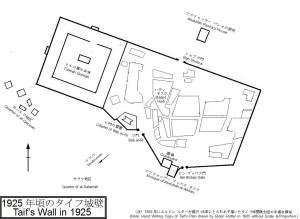

Examples of castles and towers in Southern Ḥijāz are countless. Let’s mention here: the square watchtower in Muhail ʿAsīr (around 1850); the four-storey Qaṣr Shubra of Ṭā’if (a 1925 site plan in the picture 18 to the left) (torn down in around 1858, rebuilt in the early 1900’s and today Museum of Arab and Muslim Traditions), named after a similar Cairo palace, and showing mashrabiyas of wood from Turkey and formal entrance stairs with marble imported from Italy; Qaṣr al-Muwaih (in the Makkah Region), built by the Ottomans; the Castle with twin towers of al-Bāha (in the namesake region); the Castle of Jabal Fayfā’ (in the Jāzān Region).

Examples of castles and towers in Southern Ḥijāz are countless. Let’s mention here: the square watchtower in Muhail ʿAsīr (around 1850); the four-storey Qaṣr Shubra of Ṭā’if (a 1925 site plan in the picture 18 to the left) (torn down in around 1858, rebuilt in the early 1900’s and today Museum of Arab and Muslim Traditions), named after a similar Cairo palace, and showing mashrabiyas of wood from Turkey and formal entrance stairs with marble imported from Italy; Qaṣr al-Muwaih (in the Makkah Region), built by the Ottomans; the Castle with twin towers of al-Bāha (in the namesake region); the Castle of Jabal Fayfā’ (in the Jāzān Region).

FarasānIslands belong to the just mentioned Jāzān Region, where features of buildings have developed into a unique architecture typifying these islands:

- houses of limestone and adobe;

- interior walls decorated with ornately mashrabiya-like carved gypsum patterns;

- self-styled traditional decorative interiors, moreover similar (but not the same) to certain Najdi plaster work.

On these islands you will find two coeval evidences of local architecture:

On these islands you will find two coeval evidences of local architecture:

a) Aḥmed Munawar ar-Rifā‘ī’s house (around 1922) (picture 19, right) is built of stone and the external walls of the majlis (the sitting room of important homes) are clothed by geometric plastered ledges and bars. Frescoes grace the interior of all majlis walls. Other rooms have carved gypsum walls, coloured-glass windows, and hand-painted wooden beams;

b) An-Najdi Mosque (1929) has a rectangular plan of about 560 sq.m. It encompasses two prayer halls with twelve small domes, a women’s praying area inside a further building, one minaret. The peculiarity is that its walls are chiefly composed of roughly-cut hard coral blocks covered with gypsum. As in the previous house, carved gypsum screens adorn its walls and perform well ventilation and sun-protection functions.

Najrān Region and Sharqīyah

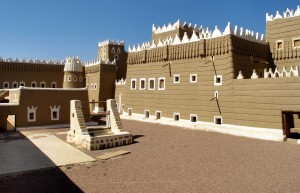

In terms of castles and palaces, however, Najrān southern Region, located along the Yemeni border and characterized by traditional mud architecture, exhibits the most significant and unique features in the Arabian Peninsula. One of the finest examples is probably Qaṣr al-‘Amārah (GovernatorateCastle) (picture 20, left), in its capital city Najrān. Built in 1944 of mud structures, with its foundations of stones, and renovated in 1986-87, it’s housing the Governor and his deputy leaders. It holds 65 rooms in 625 sq.m. and is surrounded by high walls marked by round watchtowers on the four corners. An old mosque and a pre-Islamic well testify of site antiquity. Its façades have narrow doors and high windows, in accordance with the principles of safety, defense and climate moderation; the use of gypsum is aimed to underline buildings aesthetics, as well as to protect mud structures from rapid erosion.

In terms of castles and palaces, however, Najrān southern Region, located along the Yemeni border and characterized by traditional mud architecture, exhibits the most significant and unique features in the Arabian Peninsula. One of the finest examples is probably Qaṣr al-‘Amārah (GovernatorateCastle) (picture 20, left), in its capital city Najrān. Built in 1944 of mud structures, with its foundations of stones, and renovated in 1986-87, it’s housing the Governor and his deputy leaders. It holds 65 rooms in 625 sq.m. and is surrounded by high walls marked by round watchtowers on the four corners. An old mosque and a pre-Islamic well testify of site antiquity. Its façades have narrow doors and high windows, in accordance with the principles of safety, defense and climate moderation; the use of gypsum is aimed to underline buildings aesthetics, as well as to protect mud structures from rapid erosion.

When moving in Sharqīyah (the EasternProvince), you can see old buildings and houses built of limestone and with wooden structural elements connecting buttresses. Local architecture is featured by vertical window bays in its façades, whose walls are covered by plaster or gypsum. Its roofs are generally composed of palm branches, while some others are equipped with ventilation towers, drawing air into a duct system, which, in turn, reaches inner home areas for temperature mitigation and ventilation purposes. This natural “passive” technology is similar to the one utilized in the oases of southern Iran desert zones, resulting in similarities even in the architecture and urban landscapes of both these areas facing the Gulf, that historically have been influenced each other.

In the EasternProvince you will find both Islamic vestiges and very modern universal-style housing and attempts to hybrid architecture.

In al-Hufūf, former Province capital and major urban centre in al-Ahsa Oasis, the Jawatha Mosque, built in the seventh year of Hijrā (628-29), and whose then remnants are five IX-century mud-brick small arches, was the earliest mosque built in eastern Arabia, and it followed slightly Madīnah Mosques in performing the first Friday congregation prayers. It boasts in its oral tradition (but without any historical records) of having preserved Ḥajar al-Aswad (the Black Stone) for nearly 22 years, since believers of the Ismāʿīli Qarmaṭiyya had removed it from the Ka’ba in 930. The city has also latest historical evidences, such as the early XIX-century domed Ibrāhīm Pasha Mosque or the Old Governor’s Palace, built approximately in 1907.

Dhahran and Dammām, instead, show the most modern face of the Eastern Province: one of the most interesting universal-style buildings is the Saudi Association for Energy Economics HQ in Dhahran; whilst, a traditional Islamic style is used both in the King ‘Abdul-’Azīz Royal Saudi Air Base of Dhahran and in the King Fahd International Airport of Dammām. Both of them, however, apply the latest and most sophisticated equipments, paying tribute to a running technological progress. The first, having been planned in 1961 as a civil airport, shows a minaret-like flight control tower. The latter, supposed to be the largest airport in the world in terms of area, was built starting in 1983, already completed seven years later, and made operative since 1999, by accepting also the traffic previously held by Dhahran airport. Its mosque for 2,000 worshipers, built on the car park roof, combines modern-style features with Islamic architectural elements, such as arches, domes, doors with Islamic decorations and carvings.

A case-study: the Diplomatic Quarter in Riyāḍ

Riyāḍ Diplomatic Quarter actually implements a Saudi utopian dream, or, better, it’s pretty close to it. It’s an endeavour for a urban, relational, functional, and stylistic viable integration.

Following the decision of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to transfer all diplomatic representations from Jeddah to Riyāḍ, the Master Plan of a new quarter in the capital city for at least 120 diplomatic missions and 24,000 people was set up in 1977 by local architects. Six years later, its construction began. Block 3 Centre (its core and the object of this case), completed about 30 years ago, in addition to embassies and consulates “comprises residential areas for officials and diplomats, as well as some basic cultural, religious, administrative and commercial facilities of the community, including a Friday mosque, a government service complex, a central square (Maidan), with shopping arcades, gardens, restaurants, etc.”, according to the official report of The Āgā Khan Award for Architecture.

The Centre features are inspired by a traditional Najdi architecture; in particular:

- the external walls are treated as city walls;

- projecting decorative bands mark the various floor levels;

- stepped crenellations adorn the roof levels;

- sand-colours stucco on metal lath covers outer surfaces, according to the texture of traditional mud façades.

Sequences of different spaces, plazas and landscapes areas create the traditional atmosphere of older settlements.

The organization of spaces is very rational:

- the Centre unfolds in a linear spine;

- the Block as a whole is organized around the Maidan;

- each building is designed around an inner courtyard.

The Block is accessible through two main gateways. A traffic system separating road transports and pedestrians, by leaving the Centre surface free of interferences and noise: walkers get in on the ground level and vehicles on lower level, where parking and service access are available.

Maidan (crowded every day at night, during holidays and special events) is bordered by shaded riwak (arcades) on two sides. The Friday mosque (for 7,000 worshipers) shuts a Maidan side along the traditional patterns of a Najdi design: a gateway marked by two tall minarets drives to the mosque hypostyle ṣaḥn, and then to the prayer hall; green spaces with fountains are also provided.

The buildings of the Government complex are organized around the central atrium, which is used as a cooling space, and a number of open courtyards.

The Āgā Khān Award for Architecture, which rewarded the Centre Block 3 in 1989, speaks of “an ideal model for cities in Islamic and Arab societies for having attractively preserved the traditional link between the mosque and the other public services of the city. The landscaping of the entire project has been planned as a self-sustaining ecological system, using, where appropriate, plant materials to be found in the surrounding desert environment. The jury found the landscaping to be a realistic and imaginative understanding of the natural and spatial organisation in hot and arid regions”.

Ultimately, this is an example of integration between Islamic tradition and technological development, a model for the Muslim Umma as a whole. This is what Saudi Arabia can realize today and rightly may dream implementing in its near future!

Bibliography

- Abdelhalim, Halim: Diplomatic Quarter Central Area, Block 3 Centre, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 1989 Technical Review Summary, in Al-Kindi Plaza, The Aga Khan Award for Architecture, 1989;

- al-Asad Mohammad: Saudi Mosques. Jeddah and Medina, Saudi Arabia, 1989 Technical Review Summary, in Corniche Mosque, The Aga Khan Award for Architecture, 1989;

- D’Agostino, Glauco: Sulle Vie dell’Islam. Percorsi storici orientati tra dottrina, movimentismo politico-religioso e architetture sacre (Historical and Architectural Itineraries across the Muslim Countries), Gangemi, Rome, Italy, June 2010;

- Dethier, Jean: Down to earth, Thames and Hudson, London, 1982;

- Grabar, Oleg: Muqarnas. An Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture, E. J. Brill, Leiden, The Netherlands, 1991;

- Gause, F. Gregory III: Kings for All Seasons: How the Middle East’s Monarchies Survived the Arab Spring, Brookings Doha Center Analysis Paper n. 8, September 2013;

- Ḥāmid, Aḥmad: Hassan Fathy and Continuity in Islamic Architecture. The Birth of a New Modern, The AmericanUniversity in Cairo Press, New York, NY, 2010;

- al-Hariri-Rifai, Wahbi & al-Hariri-Rifai, Mokhless: The Heritage of The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, GDG Publications, Washington, D.C. 1990;

- al-Ibrahim, Mohammed Hossein: The Criticism of Modern Architecture in Saudi Arabia, in Architecture and Planning, vol. 2, Journal of King Saud University, Riyadh, 1990;

- Kerr, Laurie: The Mosque to Commerce, Culturebox, Dec. 28 2001;

- al-Khil, Ibrahim Abdallah: Town Planning in Arab and Islamic Countries, Albenaa Architecture Magazine, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 1st year, n. 2, April / May, 1979;

- Mileto C., Vegas F., García L., Cristini V.: Vernacular Architecture. Towards a Sustainable Future, CRC Press / Balkema, Leiden, The Netherlands, 2015;

- Noakes, Greg: The Servants of God’s House, Saudi Aramco World, January / February 1999;

- Petersen, Andrew: Dictionary of Islamic Architecture, Routledge, London, 1996;

- Sedgwick, Mark J. – Against the Modern World: Traditionalism and the Secret Intellectual History of the Twentieth Century, Oxford University Press, 2004.