By Glauco D’Agostino

This article was first published in “Geopolitica. Revistă de Geografie Politică, Geopolitică şi Geostrategie”, Anul XIII, nr. 62 (4 / 2015) “Target: EUROPE”, Editura “Top Form”, Asociaţia de Geopolitica Ion Conea, Bucureşti, 2015.

Summary. Beyond an obvious disapproval of war and its adverse effects, there is a kind of inaction in acknowledging artistic heritage and symbolic historic sites as a means of harmony among peoples, just in a spirit to refine the civic and social feeling art brings with it, regardless of the civilization expressing it. This is also a political function! This is why the protection of artistic and cultural heritage is a civic duty, even during conflicts, because of its commitment of recovering the sense of community, even in presence of a feeling of confusion and displacement.

Summary. Beyond an obvious disapproval of war and its adverse effects, there is a kind of inaction in acknowledging artistic heritage and symbolic historic sites as a means of harmony among peoples, just in a spirit to refine the civic and social feeling art brings with it, regardless of the civilization expressing it. This is also a political function! This is why the protection of artistic and cultural heritage is a civic duty, even during conflicts, because of its commitment of recovering the sense of community, even in presence of a feeling of confusion and displacement.

Damage to an architectural complex or an archaeological site comprise a broad range of cases, and could be not only of material and structural nature. Generally, they can be categorized according to the following scheme: material damages; additional damages (without excluding resulting material damages); moral damages.

Abuses by warring parties on historical, artistic and architectural heritage are apparent, which implies not only a lack of sensitivity to the common feeling of affected populations and to the value of historical record, but also an infringement of international law according to the agreements and treaties regulating war laws and crimes.

The problem is cultural sensitivity and that sovereign institutions should adhere to a model of ethical behaviour, which demands, even in wartime, respect for the enemy, and especially for the historical legacy of its guiltless people. But, sadly, sometimes the State is hardly ethical!

Historical, symbolic and / or identity significance of architecture

The recent destruction of the Arch of Triumph in Palmyra (photo 1 by author, at the opening) last October 5th, has shaken the entire world’s conscience, because of the archaeological importance covered by this civil architecture masterpiece from the Roman era, and has raised the unresolved issue of artwork preservation and protection during war events or political upheavals. It’s also true that the precious Arch, built by Emperor Septimius Severus during his rule between 193 and 211 A.D., has not been the only loss in Palmyra, because earlier June 24th two shrines (the XVI-century home-born religious Abū Baha ed-Dīn’s, and Shaykh Moḥammed ‘Alī’s, a descendent of ‘Alī ibn Abū Ṭālib) have been blown up, and August 30th the Temple of Baal (photo 2 by author, left), which was founded in 32 A.D., suffered a similar fate.

The recent destruction of the Arch of Triumph in Palmyra (photo 1 by author, at the opening) last October 5th, has shaken the entire world’s conscience, because of the archaeological importance covered by this civil architecture masterpiece from the Roman era, and has raised the unresolved issue of artwork preservation and protection during war events or political upheavals. It’s also true that the precious Arch, built by Emperor Septimius Severus during his rule between 193 and 211 A.D., has not been the only loss in Palmyra, because earlier June 24th two shrines (the XVI-century home-born religious Abū Baha ed-Dīn’s, and Shaykh Moḥammed ‘Alī’s, a descendent of ‘Alī ibn Abū Ṭālib) have been blown up, and August 30th the Temple of Baal (photo 2 by author, left), which was founded in 32 A.D., suffered a similar fate.

The mention of these blameworthy episodes helps to introduce the topic of conflicts negative effects on architectural heritage (unfortunately too frequent in recent history), of the diversified features and reasons leading to these destructive effects, from the intentional ones to the so called “collateral damages”, up to identifying historical, symbolic and / or identity meanings of architecture as an expressive, as well as “political”, phenomenon.

Aldo Rossi, the well-known Italian Pritzker Prize architect, wrote in his book The Architecture of the City: “The city itself is the collective memory of its people, and like memory it is associated with objects and places”. Therefore, a plastic manifestation of a common feeling, and, as such, aimed to build an identity and a common political and civil action of society. “Material product of politics”, says Eyal Weizman, the Israeli Director of the Centre for Research Architecture at Goldsmiths, University of London. Whenever conditions are established where an internal or external entity challenges that feeling or that ideal and material system, or even that historical meaning, then the architecture as identity and political symbol risks a destruction or a deliberate damage, which mostly disguise its devastating intention. Some rhetoric justifications on “collateral damages” often fall into this category.

Frequently, architecture is used by governments as a current power representation or as an emblem of a historical past it evokes. Political crises succeeding an institutional power fall could arouse in a desire of population or certain its groups for revenge targeting the artistic heritage, habitually earlier manipulated, and then perceived as that power metaphor. Similarly, a devastating fury of a State or international coalition against its counterpart during a war, makes sometimes no distinction between military targets and artistic sites (not to mention other civilian targets), just because of the (disguised) will to hit the nation image, to demonstrate its inherent weakness, and assert its superiority. Robert Bevan, a journalist and heritage consultant, in his book The Destruction of Memory: Architecture at War, speaks of “cultural genocide”, ultimately proposing the elevation of it to a crime punishable by international law.

Conversely, beyond an obvious disapproval of war and its adverse effects, there is a kind of inaction in acknowledging artistic heritage and symbolic historic sites as a means of harmony among peoples, just in a spirit to refine the civic and social feeling art brings with it, regardless of the civilization expressing it. This is also a political function! This is why the protection of artistic and cultural heritage is a civic duty, even during conflicts, because of its commitment of recovering the sense of community, even in presence of a feeling of confusion and displacement.

Typing of damage to property and causes of conflicts from which they originate

Damage to an architectural complex or an archaeological site comprise a broad range of cases, and could be not only of material and structural nature. Generally, they can be categorized according to the following scheme: Material damages

- destruction or serious drop of structure and ornamental features;

- deterioration of urban, rural or environmental spaces (as in the case of extensive bombing on cities or their relevant parts);

- archives deliberately wiped out as part of an ethnic cleansing policy.

Additional damages (without excluding resulting material damages)

- looting;

- occupation or military operations in or around a complex (particularly archaeological sites and ancient towns);

- making areas or buildings inaccessible;

- erection of walls and fences;

- confiscation.

Moral damages

- imposition of architectural style and renaming of inhabited places or historic sites in occupied settlements;

- overlap of an alien spatial and historical storyline (planned act of eradicating a culture reminiscence, by re-interpretation and re-appropriation of space, landscape and places of memories).

On the other hand, causes that trigger the conflicts bringing the aforementioned damages could be established by the following events:

International crises:

- war among nations or coalitions (e.g., Indochina Wars, Cyprus-Turkey War, Iraq-Iran War, Iraq-Kuwait War, Operation Desert Storm, NATO bombing of Serbia, Israel-Gaza War);

- independence wars (e.g., in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina)

- occupation or colonisation of territories (e.g., in Tibet, Lebanon, Nagorno-Karabakh, Eritrea, Iraq, West Bank).

Internal factors:

- implosion of a State (e.g., Vietnam, USSR, Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Libya);

- attempts at secession (e.g., Biafra in Nigeria, Balochistan in Pakistan, Cyrenaica in Libya);

- ethnic and religious cleansing (e.g., Arab villages in Israel, Tibetan monasteries after Chinese occupation, mosques and churches in the Balkans, Azeri-populated towns in the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic, kuffār and non-Islamic people in the Islamic State);

- uprising and political riots (e.g., Civil Wars in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Côte d’Ivoire, Afghanistan and Syria, II Intifāḍa in Palestine, Army-Tālibān War in Pakistani Swat Valley);

- real estate development (e.g., tearing of ancient tombs at Cyrene, in Libya).

Examples of architectural heritage destructions in the ancient past

Nowadays, war technology development has made the destructive capacity towards artistic heritage much easier and pernicious. This appears even more unbearable to sensitivity of experts in this field and to public opinion, which are increasingly concerned and reactive in condemning human devastating events. But in the past, the limited technological reach of destructive weapons hasn’t produced results less negative to the patrimony and the very existence of the human settlements.

Nowadays, war technology development has made the destructive capacity towards artistic heritage much easier and pernicious. This appears even more unbearable to sensitivity of experts in this field and to public opinion, which are increasingly concerned and reactive in condemning human devastating events. But in the past, the limited technological reach of destructive weapons hasn’t produced results less negative to the patrimony and the very existence of the human settlements.

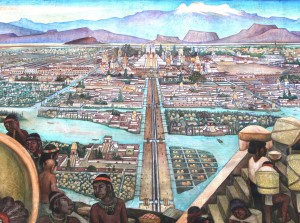

We recall the annihilation of some glorious cities that never again come back to the brightness of their power in the role of a great civilization centre: first, the Punic Carthage, which in 146 B.C. Rome razed to the ground with its temples, circle docks complex, multi-storey apartment blocks, city walls, and which it sowed with salt. Then, the humiliation suffered by Tenōchtitlān and Tlatelolco twin cities (photo 3 above by Wolfgang Sauber, 09.04.2008, from the Mural by Diego Rivera, Mexico City, Palacio Nacional), which together formed the capital of the Aztec Empire and one of the World biggest urban agglomerations of the time. On August 13th, 1521, the Conquistadores plundered it, and immediately after filled its canals, and leveled its heritage, consisting of temples, ziggurats and palaces. Their stones were used for building the present Catholic Cathedral of Santiago Tlatelolco, just on the site of a big Aztec pyramid. By showing a great symbolic and evocative sense, in 1967 the Treaty of Tlatelolco banned nuclear weapons throughout Latin America. The British conquest of Dehlī (the Old City on photo 4 by author, left) on September 21st, 1857, was equally dishonourable, because of the destruction fierceness, with effects comparable to the collapse would be produced in Dresden in 1945 (photo 5 below from Deutsche Fotothek): the occupying forces placed their artillery on the esplanade of Masjid-i-Jahān-Numā, the main mosque of the Mughal Empire, destroying the surrounding area within the guns range, including an incomparable architectural, cultural, artistic, literary and objects heritage.

We recall the annihilation of some glorious cities that never again come back to the brightness of their power in the role of a great civilization centre: first, the Punic Carthage, which in 146 B.C. Rome razed to the ground with its temples, circle docks complex, multi-storey apartment blocks, city walls, and which it sowed with salt. Then, the humiliation suffered by Tenōchtitlān and Tlatelolco twin cities (photo 3 above by Wolfgang Sauber, 09.04.2008, from the Mural by Diego Rivera, Mexico City, Palacio Nacional), which together formed the capital of the Aztec Empire and one of the World biggest urban agglomerations of the time. On August 13th, 1521, the Conquistadores plundered it, and immediately after filled its canals, and leveled its heritage, consisting of temples, ziggurats and palaces. Their stones were used for building the present Catholic Cathedral of Santiago Tlatelolco, just on the site of a big Aztec pyramid. By showing a great symbolic and evocative sense, in 1967 the Treaty of Tlatelolco banned nuclear weapons throughout Latin America. The British conquest of Dehlī (the Old City on photo 4 by author, left) on September 21st, 1857, was equally dishonourable, because of the destruction fierceness, with effects comparable to the collapse would be produced in Dresden in 1945 (photo 5 below from Deutsche Fotothek): the occupying forces placed their artillery on the esplanade of Masjid-i-Jahān-Numā, the main mosque of the Mughal Empire, destroying the surrounding area within the guns range, including an incomparable architectural, cultural, artistic, literary and objects heritage.

These are some of the most outstanding episodes of urban devastation occurred in history. But, of course, there are countless past war events having cleared very important architectural evidence, starting with entire historic complexes, up to individual stylistic examples from different cultures. For example, Susa, one of the main cities of the Ancient Near East, was leveled in 647 B.C. by the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal, who boasted of having “entered its palaces, opened their treasuries where silver and gold, goods and wealth were amassed … destroyed the ziggurat … reduced the temples of Elam to naught; their gods and goddesses I scattered to the winds. The tombs of their ancient and recent kings I devastated … I devastated the provinces of Elam and on their lands I sowed salt”.

These are some of the most outstanding episodes of urban devastation occurred in history. But, of course, there are countless past war events having cleared very important architectural evidence, starting with entire historic complexes, up to individual stylistic examples from different cultures. For example, Susa, one of the main cities of the Ancient Near East, was leveled in 647 B.C. by the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal, who boasted of having “entered its palaces, opened their treasuries where silver and gold, goods and wealth were amassed … destroyed the ziggurat … reduced the temples of Elam to naught; their gods and goddesses I scattered to the winds. The tombs of their ancient and recent kings I devastated … I devastated the provinces of Elam and on their lands I sowed salt”.

More sufficient to recall the destructions of Bet HaMikdash (the Holy Temple in Jerusalem): the first one, by the Babylonians in 587 B.C., the second by the Romans on August 9th, 70 A.D., when the Jewish Diaspora began; or the pointless 1789 storming of Paris Bastille early July 14th, just because it was a symbol bound to monarchy; or Napoleon’s looting during his campaign, that contributed to Louvre Museum fortunes; or the devastation of Manila (photo 6 right on May 1945) in the brutal battle between US and Japan in February-March 1945: the religious heritage, as well as a civil architecture dating back to the founding of the city, were shattered (afterwards, an American-style architecture replaced an aesthetic environment that was a confluence of Spanish, American and Asian cultures); to say nothing of material and moral damage resulting from one of the largest mass murders in history, performed in August 1945 in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, with a total elimination of entire neighborhoods of both cities.

More sufficient to recall the destructions of Bet HaMikdash (the Holy Temple in Jerusalem): the first one, by the Babylonians in 587 B.C., the second by the Romans on August 9th, 70 A.D., when the Jewish Diaspora began; or the pointless 1789 storming of Paris Bastille early July 14th, just because it was a symbol bound to monarchy; or Napoleon’s looting during his campaign, that contributed to Louvre Museum fortunes; or the devastation of Manila (photo 6 right on May 1945) in the brutal battle between US and Japan in February-March 1945: the religious heritage, as well as a civil architecture dating back to the founding of the city, were shattered (afterwards, an American-style architecture replaced an aesthetic environment that was a confluence of Spanish, American and Asian cultures); to say nothing of material and moral damage resulting from one of the largest mass murders in history, performed in August 1945 in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, with a total elimination of entire neighborhoods of both cities.

Destructions of architectural heritage in the recent major conflicts

Indochina Wars (1945-75)

The thirty-year war that upset Vietnam developed across two separate conflicts: the first, fought by France against its Việt Minh foes between the 1945 establishment of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam and the 1954 recognition of country temporary division along the 17th parallel; the second, which also involved Laos and Cambodia, fought by North Vietnam and South Vietnam (the prior supported by the Việt Cộng, USSR, China and other communist allies, and the latter by US and other anti-communist allies), starting with the 1956 Việt Cộng low-level insurgency in South Vietnam, to the Sài Gòn fall by North Vietnamese and Việt Cộng troops on April 30th, 1975.

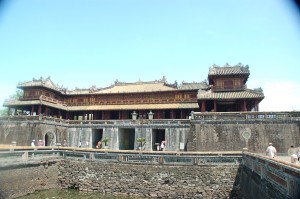

Vinh, the capital of the northern Nghệ An Province, and Huế, the ancient capital of Vietnam as a whole between 1802 and 1945, both of them historical and artistic sites of relevant importance, are two martyred cities of these wars because of the damage they suffered.

Vinh was known for its ancient citadel, up to its utter destruction given in the 50’s during the First Indochina War and by US bombing in the Second War. Huế (the Imperial Citadel in photo 7 by author on the left) has been reduced to rubble on January 31st, 1968, by US bombing during the Tết offensive replying Communist capture of the city, and as part of the Operation Rolling Thunder begun in 1965. But also the extensive damage to the capital Hà Nội and to Hải Phòng, the largest port of North Vietnam, during the 1972 Operation Linebacker II are to be remembered.

Vinh was known for its ancient citadel, up to its utter destruction given in the 50’s during the First Indochina War and by US bombing in the Second War. Huế (the Imperial Citadel in photo 7 by author on the left) has been reduced to rubble on January 31st, 1968, by US bombing during the Tết offensive replying Communist capture of the city, and as part of the Operation Rolling Thunder begun in 1965. But also the extensive damage to the capital Hà Nội and to Hải Phòng, the largest port of North Vietnam, during the 1972 Operation Linebacker II are to be remembered.

Iraq-Iran War (1980-88)

This conflict started when Iraq invaded the Islamic Republic of Iran and caused damage to the artistic heritage mainly of the Iranian province of Khūzestān, regarded as the “birthplace of the nation”, since its city Susa was the Elamite capital city, one of 4 capitals of the Achaemenid Persian Empire, and one of the two capitals of the Parthian Empire. Many cities have been almost completely destroyed by the invading Iraqi army, like Khorramshahr, the most important Iranian port prior to the war, has been. Some others suffered the shelling of cultural and historic sites, like Susa (photo 8, right) and Ābādān.

This conflict started when Iraq invaded the Islamic Republic of Iran and caused damage to the artistic heritage mainly of the Iranian province of Khūzestān, regarded as the “birthplace of the nation”, since its city Susa was the Elamite capital city, one of 4 capitals of the Achaemenid Persian Empire, and one of the two capitals of the Parthian Empire. Many cities have been almost completely destroyed by the invading Iraqi army, like Khorramshahr, the most important Iranian port prior to the war, has been. Some others suffered the shelling of cultural and historic sites, like Susa (photo 8, right) and Ābādān.

Iraq-Kuwait War (1990-91) and Operation Desert Storm (1991)

The Iraqi occupation and annexation of Kuwait has damaged the National Museum in Kuwait City, which was looted of 30,000 pieces of Islamic art collection. But the ensuing Operation Desert Storm in January-February 1991, executed by a US-led coalition of 34 nations against Iraq, resulted in major damage to the Iraqi historical and artistic heritage.

Tell al-Lahm, the modern site of the Sumerian Gulf seaport of Ku’ara founded in the 25th century B.C., has been partially razed by U.S. troops to install firing positions.

The Neo-Sumerian Great Ziggurat of the ancient Ur city-state (photo 9 on the right by Hardnfast, 20 September 2005), close to the modern Nāşirīya, is well-known. The huge building, dating back to the 21st century B.C. and already decayed 15 centuries later, in 1991 has been targeted by shots of small firearms, which damaged its brickwork. Furthermore, an attack on a nearby Iraqi air base ditched four big bomb craters just about the ziggurat tower and hundreds of holes in one of its reconstructed walls.

The Neo-Sumerian Great Ziggurat of the ancient Ur city-state (photo 9 on the right by Hardnfast, 20 September 2005), close to the modern Nāşirīya, is well-known. The huge building, dating back to the 21st century B.C. and already decayed 15 centuries later, in 1991 has been targeted by shots of small firearms, which damaged its brickwork. Furthermore, an attack on a nearby Iraqi air base ditched four big bomb craters just about the ziggurat tower and hundreds of holes in one of its reconstructed walls.

The archaeological site of Ctesiphon, the capital city of the Parthian and Sasanian Empires, suffered air attacks on a nearby weapons depot, causing serious cracks in the 4th century A.D. Ṭāq-e Kesrā (the īwān of Sasanian Shāhanshāh Chosroes I, photo 10, right), the largest single-span vault of unreinforced brickwork in the world. Its restoration started in 2013 in cooperation with the University of Chicago.

The archaeological site of Ctesiphon, the capital city of the Parthian and Sasanian Empires, suffered air attacks on a nearby weapons depot, causing serious cracks in the 4th century A.D. Ṭāq-e Kesrā (the īwān of Sasanian Shāhanshāh Chosroes I, photo 10, right), the largest single-span vault of unreinforced brickwork in the world. Its restoration started in 2013 in cooperation with the University of Chicago.

Yugoslavia implosion: the aftermath (1991-2002)

The gradual disintegration of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia started when Croatia, Slovenia and Macedonia declared their independence in 1991, followed by Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1992. The resulting conflicts between Yugoslav People’s Army and the separatists, which are usually treated as separate wars although they are linked by the same motivations, mainly related to Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, so a distinction is made between the Croatian War, fought between 1991 and 1995, and Bosnia and Herzegovina War between 1992 and the signing of the General Framework Agreement for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina on December 14th, 1995. But the Kosovo War, too, that has lasted 17 months between 1998 and the 1999 establishment of the UN Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo and was fought by the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia against the Kosovo Liberation Army (since March 1999 supported by the Albanian army and NATO), is part of the same separatist scenario.

The most important damaged places in Croatia have been the World Heritage sites of Dubrovnik, Split and the Plitvice Lakes National Park in 1991 and 1992: among them, the ancient walled city of Dubrovnik was shelled, 56% of its civil and religious buildings were damaged to some degree and 9 buildings totally destroyed. Also the town of Vukovar suffered heavy damage of its architectural heritage (Baroque buildings, the Franciscan monastery, the 18th century Eltz Manor, the water tower) and a steady deterioration of its urban spaces.

The greatest damage to the architectural heritage in Bosnia and Herzegovina mainly concerned the historical and religious buildings, and among them some 1,500 mosques were dynamited and razed to the ground. In Bosanska Krajina, Banja Luka, the largest city of the 1992-self-proclaimed Republika Srpska, saw all its 16 mosques destroyed, including the 16th century Ottoman Mosques named Ferhat-pašina (now under rebuilding, as from photo 11 on the left by Zlatno krilo, 2 January 2014), the major symbol for all its inhabitants, and the nearby Arnaudija.

The greatest damage to the architectural heritage in Bosnia and Herzegovina mainly concerned the historical and religious buildings, and among them some 1,500 mosques were dynamited and razed to the ground. In Bosanska Krajina, Banja Luka, the largest city of the 1992-self-proclaimed Republika Srpska, saw all its 16 mosques destroyed, including the 16th century Ottoman Mosques named Ferhat-pašina (now under rebuilding, as from photo 11 on the left by Zlatno krilo, 2 January 2014), the major symbol for all its inhabitants, and the nearby Arnaudija.

The 1992-95 siege of the multi-ethnic city of Sarajevo, with its 80,000 bombing, has severely affected its rich blend of cultures and architectures, because it sought undermining a hundred years of Muslims, Turks, Serbs, Croats, and Jews peaceful coexistence, and because it has sternly injured its physical structure, especially its most interesting neighbourhoods, as the old Oriental and the Art Nouveau Viennese districts. Along with its 15th century public buildings and mosques and the Olympic facilities, we want to recall two fine institutions of Stari Grad (the Old town) which have been targeted and almost completely destroyed as a priority, due to their symbolic value to the city: the Institute for Oriental Studies, which contained most of Bosnian historical and literary documents, and the Austro-Hungarian eclectic, predominantly pseudo-Moorish Vijećnica, that housed the National and University Library of Bosnia and Herzegovina and is now a national monument (photo 12 above by author).

The 1992-95 siege of the multi-ethnic city of Sarajevo, with its 80,000 bombing, has severely affected its rich blend of cultures and architectures, because it sought undermining a hundred years of Muslims, Turks, Serbs, Croats, and Jews peaceful coexistence, and because it has sternly injured its physical structure, especially its most interesting neighbourhoods, as the old Oriental and the Art Nouveau Viennese districts. Along with its 15th century public buildings and mosques and the Olympic facilities, we want to recall two fine institutions of Stari Grad (the Old town) which have been targeted and almost completely destroyed as a priority, due to their symbolic value to the city: the Institute for Oriental Studies, which contained most of Bosnian historical and literary documents, and the Austro-Hungarian eclectic, predominantly pseudo-Moorish Vijećnica, that housed the National and University Library of Bosnia and Herzegovina and is now a national monument (photo 12 above by author).

Another city which, like Sarajevo, saw the whole urban system injured is Mostar, the most destroyed urban settlement during the war, and whose name comes from the Serbo-Croatian word “most” (the bridge). And right one of its bridge is left in the everyone’s memory as a paradigm of a fierce and senseless war: the 16th century Ottoman stone Stari Most, designed in 1566 by Mi’mâr Hajruddin (a pupil of the Turkish Imperial architect Mi’mâr Sinân Âğâ), has been destroyed on November 9th, 1993, and later rebuilt in 2004 (photo 13 on the left by Alistair Young, 27 August 2008).

Another city which, like Sarajevo, saw the whole urban system injured is Mostar, the most destroyed urban settlement during the war, and whose name comes from the Serbo-Croatian word “most” (the bridge). And right one of its bridge is left in the everyone’s memory as a paradigm of a fierce and senseless war: the 16th century Ottoman stone Stari Most, designed in 1566 by Mi’mâr Hajruddin (a pupil of the Turkish Imperial architect Mi’mâr Sinân Âğâ), has been destroyed on November 9th, 1993, and later rebuilt in 2004 (photo 13 on the left by Alistair Young, 27 August 2008).

Even Belgrade was bombed by NATO air strikes, in the context of the Operation Noble Anvil, triggered in 1999 between March and June with no UN Security Council approval: one of the most embarrassing bombed targets was the Chinese embassy, as well. During April and May, Kneza Miloša Street as a whole, a major downtown artery with scenic and architectural features, was bombed quite a lot of times, resulting in the destruction of many institutional buildings and the damage of several others of artistic interest. Indeed, all the buildings in this street show considerable architectural and stylistic quality, due to ornamentations of their façades, decorations of their interiors and sculptures, paintings, and artistic objects contained inside.

Palestinian II Intifāḍa (2000-05) and Israel-Gaza War (2014)

The Second Intifāḍa and Israel-Gaza War are rooted in the effects of the Jewish State establishment in Tel Aviv on May 14th, 1948 (5th, Iyar, 5708 in the Jewish calendar) and in the nearly constant conflicts between Israelis and Palestinians since have resulted. Then, on November 15th, 1988, the declaration of a Palestinian State in fieri, with East Jerusalem as its capital, and on May 4th, 1994, the setting up of the Palestinian National Authority as an autonomous institutional entity.

Also known as al-Aqṣā Intifāḍa, the Second Intifāḍa started in September 2000, when Ariʼēl Sharōn, the future 11th Prime Minister of Israel, challenged them (according to Palestinian feeling) by visiting the Temple Mount. The 2014 Israel-Gaza War was a military operation called Operation Protective Edge, launched by Israel on July 8th until August 26th, 2014, against the Ḥamās-ruled Gaza Strip.

During the Second Intifāḍa, Israel destroyed or harmed many Palestinian historical, cultural and religious sites throughout the Occupied Territories. Ḥebron, the old city of Bethlehem and its Church of the Nativity suffered from irreparable damage. The Old City of Nāblus, which boasts mosques, churches, mausoleums, khans, bath houses, and historic houses among its heritage, had most of the architectural injure, because they include assets dating back to Roman, Byzantine, Crusader, Mamluk and Ottoman eras. Between April 2002 and March 2003, Israeli military forces launched air and ground offensives against Nāblus. Many sites suffered destruction, such as: Masjid al-Khadra, the oldest city mosque; the 17th century St. Demetrios Greek Orthodox Church; al-Wakalat Khan; and also al-Jadīdeh Ḥammām, al-Fāṭimiyeh female preparatory school, Kanaan an-Nabulsi Soap Factories and both Shuby and Hosh Freitekh residential complexes, all of the latter built in the Ottoman era.

As of 2001, when the “Public Movement for The Security Fence” coaxed the Israeli government for building a barrier separating the Palestinian territories from Israel (photo 14 on the right in East Jerusalem), the West Bank underwent a deterioration of urban spaces, as well as the impact of policies of colonization and ethnic and religious cleansing. Sherin Sahouri, Head of the Maintenance and Restoration Department within the Department of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage in Rāmallāh, puts it this way: “Another major threat to Palestinian heritage is the separation wall constructed by Israel in the occupied Palestinian territory, including in and around Jerusalem. This is a huge system of concrete walls, razor wire, trenches and fences, cutting into the West Bank and Gaza and separating people from their land and history. The great impacts of the wall on Palestinian daily life are not only economic and social, but also entail a destructive impact on numerous important archaeological remains, heritage sites and cultural landscapes”.

As of 2001, when the “Public Movement for The Security Fence” coaxed the Israeli government for building a barrier separating the Palestinian territories from Israel (photo 14 on the right in East Jerusalem), the West Bank underwent a deterioration of urban spaces, as well as the impact of policies of colonization and ethnic and religious cleansing. Sherin Sahouri, Head of the Maintenance and Restoration Department within the Department of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage in Rāmallāh, puts it this way: “Another major threat to Palestinian heritage is the separation wall constructed by Israel in the occupied Palestinian territory, including in and around Jerusalem. This is a huge system of concrete walls, razor wire, trenches and fences, cutting into the West Bank and Gaza and separating people from their land and history. The great impacts of the wall on Palestinian daily life are not only economic and social, but also entail a destructive impact on numerous important archaeological remains, heritage sites and cultural landscapes”.

During the 2014 Israel-Gaza War, the third major offensive in Gaza since 2008, the Gaza Strip suffered harms in its architectural heritage, along with 7,000 demolished homes, 89,000 damaged, and 60,000 homeless people as a result. Among all, the historic sandstone Jāmaʿ al-ʿUmarī al-Kabīr (photo 15, right), the Great Mosque of Gaza located in the old city, was bombed by Israeli forces on August 2nd, 2014, and almost completely destroyed. Its portico and minaret dated back to the Mamluk era.

During the 2014 Israel-Gaza War, the third major offensive in Gaza since 2008, the Gaza Strip suffered harms in its architectural heritage, along with 7,000 demolished homes, 89,000 damaged, and 60,000 homeless people as a result. Among all, the historic sandstone Jāmaʿ al-ʿUmarī al-Kabīr (photo 15, right), the Great Mosque of Gaza located in the old city, was bombed by Israeli forces on August 2nd, 2014, and almost completely destroyed. Its portico and minaret dated back to the Mamluk era.

Iraq War (2003-11 and 2014-present)

Iraq War consisted of three phases: the March-April 2003 invasion of Iraq by a US-led coalition under the code name Operation Iraqi Freedom; the U.S.-led country occupation until December 2011, that was opposed by an insurgency; the Operation Inherent Resolve, established again by a U.S.-led coalition against the Islamic State in September 2014 and still active. Prior to the invasion, professional associations and leading scholars of archaeology, art and history warned US authorities about likely dangers to Iraqi cultural heritage in the event of war, and, above all, when indiscriminate military operations would have been conducted. Some of the results are listed below.

The bombing of religious buildings, a method to ignite conflicting armed forces and discourage the populace, began at once. On April 11th, 2003, the Abū Ḥanīfa Shrine in Baġdād suffered damage to the top of a tower, hit by a U.S. rocket. In the capital city also the 14th century Persian-style Mustanṣarieh Madrasa and the 16th century Saray Mosque were affected by fire or subsequent looting. On November 10th, 2004, a coalition bombardment destroyed 65 mosques in Fallūja, including the Khulafāʾ ar-Rāshid Mosque.

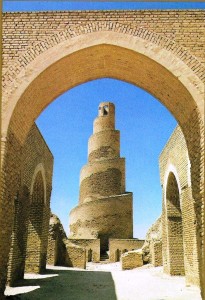

The city of Sāmarrā was particularly shocked by damage to two of its religious Iraqi masterpieces: the 9th century Arab-style spiral-shaped Malwiyya minaret (photo 16 by Mustafa Al Najjar, left); and the 10th century Persian-style al-‘Askarī Shiite Mosque and Shrine Complex.

The city of Sāmarrā was particularly shocked by damage to two of its religious Iraqi masterpieces: the 9th century Arab-style spiral-shaped Malwiyya minaret (photo 16 by Mustafa Al Najjar, left); and the 10th century Persian-style al-‘Askarī Shiite Mosque and Shrine Complex.

At the time of its edification, the 52m-high Malwiyya tower was part of the largest mosque in the world, later destroyed in 1278 by the Mongols. The minaret and the mosque were built in 851 by al-Mutawakkil (the ʿAbbāsid Caliph ruling since 847 to 861), when Sāmarrā had already been appointed new capital of the ʿAbbāsid Empire since 15 years. From September 2004 to March 2005 the minaret had been used by US military as a guard site. On April 1st, 2005, the minaret crest was shelled by insurgents, in an evident endeavour to stop snipers. The minaret outside was restored in the 1990’s. Instead, al-‘Askarī Mosque is one of the most important Shiite mosques in the world (following Najaf and Kerbala): it houses the remains of ‘Alī al-Hādī and his son Ḥasan al-‘Askarī, respectively 10th and 11th Twelver Shiite Imām, and is located next to the temple of the Imām-Māhdī Abū ‘l-Qāsim Hujjat Muḥammad, the hidden 12° Imām. On February 22nd, 2006, it was bombed and severely damaged, and in 2009 its golden dome and minarets were rebuilt.

Also several out of 12,000 archaeological sites located in the country were not spared from conflict effects. Permanent injure has occurred to the ancient sites of Babylon, Ur and Kish, due to an illegal occupation by coalition forces and the placement of large encampments or the digging of trenches close to these sites. At Ur, bomb craters can be seen in the surrounding areas, and the aforementioned Neo-Sumerian Great Ziggurat was hit again, after being targeted in 1991 Operation Desert Storm.

Unforgiving impacts on old neighbourhoods with historical and artistic value occurred during the siege by coalition forces. In August-September 2004, the central area of Najaf holy city (Imām ‘Alī ibn Abū Ṭālib’s Holy Shrine in photo 17, left) was destroyed during the Second Insurrection, when the US-led coalition countered the Jaysh al Māhdī (Māhdī Army) paramilitary of the Shiite theologian Sayyed Muqtadā aṣ-Ṣadr. In the following November, aerial and ground attacks from the same coalition destroyed old buildings in Tal ʿAfar, Ramādī and Sāmarrā.

Unforgiving impacts on old neighbourhoods with historical and artistic value occurred during the siege by coalition forces. In August-September 2004, the central area of Najaf holy city (Imām ‘Alī ibn Abū Ṭālib’s Holy Shrine in photo 17, left) was destroyed during the Second Insurrection, when the US-led coalition countered the Jaysh al Māhdī (Māhdī Army) paramilitary of the Shiite theologian Sayyed Muqtadā aṣ-Ṣadr. In the following November, aerial and ground attacks from the same coalition destroyed old buildings in Tal ʿAfar, Ramādī and Sāmarrā.

Other remarkable examples of civil architecture have suffered damage of various kinds: the 12th century ʿAbbāsid Palace, the Ottoman Qishla (military barracks complex), the Iraq Museum and Iraq National Archives, all of them located in Baġdād; the Mōṣul Museum has been ransacked by stealing of hundreds of precious objects, such as Assyrian artefacts from Balawat, Ninive and Nimrud.

Even before its proclamation on June 29th, 2014, the creation process of the Islamic State led to some execrable acts, even against targets of Iraqi Islamic piety, as they were deemed heterodox with respect to its own conception about Islam. Just in and around Mōṣul, it destroyed or damaged 30 shrines and 15 mosques and hosseiniyeh (halls for Shiite ritual ceremonies). Between them, Yūnis’ and Daniel’s tombs (the prior in photo 18, left), the shrines of two Prophets revered by both Christians and Muslims, have been blown up on July 24th, 2014, “in front of a large gathering of people”, according to an eyewitness.

Even before its proclamation on June 29th, 2014, the creation process of the Islamic State led to some execrable acts, even against targets of Iraqi Islamic piety, as they were deemed heterodox with respect to its own conception about Islam. Just in and around Mōṣul, it destroyed or damaged 30 shrines and 15 mosques and hosseiniyeh (halls for Shiite ritual ceremonies). Between them, Yūnis’ and Daniel’s tombs (the prior in photo 18, left), the shrines of two Prophets revered by both Christians and Muslims, have been blown up on July 24th, 2014, “in front of a large gathering of people”, according to an eyewitness.

Reporting of damage to architectural heritage in other conflicts

Occupations and / or colonisations

Apart from aforementioned forms of occupation or colonisation (in the former Yugoslavia, in Israel and Iraq), more similar actions must be recalled.

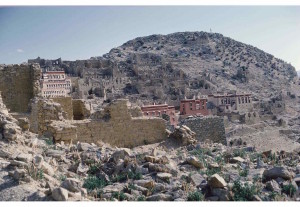

Following the 1950 Chinese occupation, between 1959 and 1961 Tibet suffered the destruction of most of its 6,000 monasteries (Ganden monastery, 1985, in photo 19, right). During the “Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution”, that lasted 10 years starting in 1966, a campaign was launched against cultural sites throughout the People’s Republic of China. Tibetan monasteries were affected again by the introduction of a secular education, and very few of them remained undamaged.

Following the 1950 Chinese occupation, between 1959 and 1961 Tibet suffered the destruction of most of its 6,000 monasteries (Ganden monastery, 1985, in photo 19, right). During the “Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution”, that lasted 10 years starting in 1966, a campaign was launched against cultural sites throughout the People’s Republic of China. Tibetan monasteries were affected again by the introduction of a secular education, and very few of them remained undamaged.

In 1974 a coup d’état, aimed to annex Cyprus to Greece, pushed Turkey to occupy the northern part of the island, which in 1983 declared its independence as Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. In 1984 UNESCO stated: “Unfortunately, in the area occupied by the Turkish army, museums and monuments have been pillaged or destroyed”. According to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Cyprus (thus, a report that might be biased) the extent of cultural property damage in the northern part is the following: 500 Greek Orthodox churches and chapels have been pillaged, vandalized, or demolished; 133 churches, chapels, and monasteries have been desecrated; the whereabouts of 15,000 paintings are unknown; and 77 churches have been turned into mosques, 28 are being used by the Turkish military forces as hospitals or camps, and 13 are used as agricultural barns.

On June 6th, 1982, in Lebanon the Peace of Galilee began. Beyond its reassuring name, it pointed to Israeli invasion of country’s south to counter Palestine Liberation Organization militias. Among the negative effects, apart from the September massacre of Palestinian refugees and Lebanese Shiite civilians gathered in the Sabra and Shatila camps, in the capital suburbs, we should remember heavy damage to Beirut (shelled by Israeli artillery and bombed by Israeli aircraft for ten weeks), to the southern cities of Sidon and Tyre and to the archaeological site of the latter.

Even before the 1991 USSR dissolution, the Artsakh Movement, operating since February 1988 in the predominantly Armenian-populated Azerbaijani Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast’, tried to attach the region to Soviet Armenia. On September 2nd, 1991, the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic was declared with an Armenian support. This is the start of the Nagorno-Karabakh War, which has been lasting since 1991 to 1994. Azeri military were shelling the capital Stepanakert from the historical town of Şuşa (or Shushi), a major Azeri stronghold in Karabakh, until the urban settlement fell down on May 9th, 1992, and was looted and burnt by Armenians. As a result, Şuşa Muslim Azeri heritage changed its features to an Iranian style and the local-style houses were moulded in Armenian fashion, in accordance with the original identity of the city.

At the end of the 1998-2000 Ethiopian-Eritrean War on sovereignty over a disputed territory along their border, Ethiopia occupied about a quarter of Eritrea in its south and west, destroying many places of its cultural heritage (e.g. sycamore trees, sacred to people as symbolic elements, some patriots’ cemeteries) and some of its important infrastructures. Among many towns and villages suffering damage, the market town of Senafe was destroyed under military occupation. The nearby archaeological site of Metera, a witness of pre-Axumite civilisation, contains the Hawulti stele (photo 20, left), the oldest example of the Old Ethiopic script dating back to the middle of the first millennium B.C., which was purposely shot down by an explosive put by Ethiopian troops.

At the end of the 1998-2000 Ethiopian-Eritrean War on sovereignty over a disputed territory along their border, Ethiopia occupied about a quarter of Eritrea in its south and west, destroying many places of its cultural heritage (e.g. sycamore trees, sacred to people as symbolic elements, some patriots’ cemeteries) and some of its important infrastructures. Among many towns and villages suffering damage, the market town of Senafe was destroyed under military occupation. The nearby archaeological site of Metera, a witness of pre-Axumite civilisation, contains the Hawulti stele (photo 20, left), the oldest example of the Old Ethiopic script dating back to the middle of the first millennium B.C., which was purposely shot down by an explosive put by Ethiopian troops.

Civil Wars in Africa

Since the 1960’s, African countries have suffered from many inner political riots. We must remember some of the harmful effects on their artistic heritage.

Following the 1960-63 Nigeria decolonisation process, the south-eastern Igbo people, one of the largest African ethnic groups, seceded from Nigeria, by proclaiming the Republic of Biafra on May 30th, 1967, that continued its function until 1970. Among the various effects on the cultural sector of the entire Nigeria, those ones suffered just in Biafra are particularly serious. A significant example is the looting of the Oron Museum, located near Calabar, today in the southern Cross River State. The museum housed hundreds Ekpu (ancestral figures, photo 21, right) of the Oron people, engraved by the inhabitants of the area, and probably the oldest and finest existing wood carving in Africa. By the end of the civil war, the extent of produced damage showed the museum had been almost completely destroyed and emptied of its major collections, including almost all Ekpu carvings. Their remains are now housed in the same renewed museum, along with other ethnographic artefacts from across Nigeria.

Following the 1960-63 Nigeria decolonisation process, the south-eastern Igbo people, one of the largest African ethnic groups, seceded from Nigeria, by proclaiming the Republic of Biafra on May 30th, 1967, that continued its function until 1970. Among the various effects on the cultural sector of the entire Nigeria, those ones suffered just in Biafra are particularly serious. A significant example is the looting of the Oron Museum, located near Calabar, today in the southern Cross River State. The museum housed hundreds Ekpu (ancestral figures, photo 21, right) of the Oron people, engraved by the inhabitants of the area, and probably the oldest and finest existing wood carving in Africa. By the end of the civil war, the extent of produced damage showed the museum had been almost completely destroyed and emptied of its major collections, including almost all Ekpu carvings. Their remains are now housed in the same renewed museum, along with other ethnographic artefacts from across Nigeria.

The 1991-2002 Sierra Leone Civil War began with a coup attempt by a nationalist group and saw the intervention of National Patriotic Front of Liberia and the British ground force. In 1999 many mosques and churches were razed to the ground.

In the same year, given the insufficient results of the 1996 Abuja Accord that ended the seven-year-long First Civil War, in Liberia a Guinea-backed group rose against the Charles McArthur Taylor’s government, thus starting the Second Civil War. In the final stage of the conflict, which ended in 2003 with the Taylor’s resignation, a US-led Joint Task Force Liberia and Côte d’Ivoire have been also involved, the latter interfering from its territory by attacks. In the last year of war, 5,000 artefacts from the National Museum in Monrovia were looted, and now some a hundred of the largest ones stay on.

Following a 2007 disarmament process ending the First Civil War, in Côte d’Ivoire a political clash between the Catholic Christian incumbent President Laurent Gbagbo and the Muslim President-elect Alassane Dramane Ouattara caused the Second Civil War in March-April 2011, until Gbagbo was captured with French troop’s assistance. During the battle for Abidjan, the Museum of Civilizations was looted.

Political riots in Asia

After USSR withdrawal from Afghanistan, as a result of April 14th, 1988 Geneva Accords, and the fall of Moḥammad Najibullah’s communist regime on June 28th, 1992, the pro-Western Tajik Burhānuddīn Rabbānī, Jamiat-e Islami Afghanistan party official leader, settled the new Islamic State of Afghanistan. This outcome was not shared by Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, Ḥizb-e Islami leader and founder, who launched a bloody civil war among winners, until Kabul was conquered on September 27th, 1996, by Sunni religious-political movement of Tālibān.

During that time, when Kabul, Mazār-i Sharīf and Kandahār have been the scene of major armed conflicts, the National Museum of Afghanistan in Kabul has been regarded as the greatest artistic loss. In May 1993, the Museum was destroyed by shelling that burned all its contents, and soon after a looting began, resulting in a stealing of more than four thousand items. The same fate has befallen to the nearby Institute of Archaeology. But even previously, starting one year before, more than 70% of the National Museum collections and the totality of Archaeological Institute objects were stolen and exported to other countries.

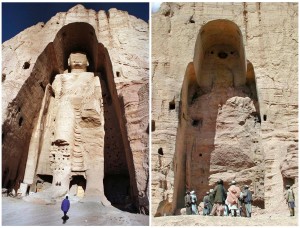

Following the 1997 formal establishment of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, with a diplomatic recognition of the United Arab Emirates, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, the Tālibān began an eradication policy of all images from the pre-Islamic past. In this period, the major act of destruction concerning artworks hit the 7th century B.C. two giant Buddha’s statues of Bamiyan (photo 22, left), cut in the surrounding sandstone cliffs of the Hazara-inhabited town of central Afghanistan. These transcendental figures from Mahayana Buddhist tradition were supposed to represent the depictions of Vairocana (or Mahāvairocana), the universal aspect of Siddhārtha Gautama, the Buddha of Wisdom (Prajñādhika Buddha), and his historical manifestation as one of the persons of the Śākyamuni Trinity (Wise men of the Śākya clan). On February 26th, 2001, Mullāh ‘Omar, Commander of the Faithful and Tālibān supreme leader, stated: “these idols have been gods of the infidels”; then, he ordered their destruction.

Following the 1997 formal establishment of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, with a diplomatic recognition of the United Arab Emirates, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, the Tālibān began an eradication policy of all images from the pre-Islamic past. In this period, the major act of destruction concerning artworks hit the 7th century B.C. two giant Buddha’s statues of Bamiyan (photo 22, left), cut in the surrounding sandstone cliffs of the Hazara-inhabited town of central Afghanistan. These transcendental figures from Mahayana Buddhist tradition were supposed to represent the depictions of Vairocana (or Mahāvairocana), the universal aspect of Siddhārtha Gautama, the Buddha of Wisdom (Prajñādhika Buddha), and his historical manifestation as one of the persons of the Śākyamuni Trinity (Wise men of the Śākya clan). On February 26th, 2001, Mullāh ‘Omar, Commander of the Faithful and Tālibān supreme leader, stated: “these idols have been gods of the infidels”; then, he ordered their destruction.

At this juncture, a weakness of UNESCO action has been highlighted when using institutional channels to achieve the protection purposes it intends; since, in the present case, that UN organization, although it was aware of the destructive intent, had trouble to alert the diplomatic network precisely because the international community did not recognize the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. The upshot was that the action could not be timely, and therefore failed to prevent the destruction of both masterpieces.

In nearby Pakistan, as well, Swat Valley, that formerly was a Vajrayāna (Tantric) Buddhist centre with about 1,400 monasteries, boasts a presence of Buddhist stupas and bas reliefs, clay-moulded Buddha’s statues and rock carvings. In November 2007, Deobandi Tālibān groups challenged the Pakistan Armed Forces, causing damage to the artistic heritage in several parts of the Valley. Among them: near Mangalore, the carved giant Buddha’s statue was attacked; in the small village of Jehanabad, the Seated Buddha’s face was dynamited; Kushan-era stupas and statues were demolished; the hill station of Maalam Jabba was destroyed; the Swat Museum, containing collections of Gandhāra sculptures, is currently occupied by Pakistan Army.

But Pakistan also faces attempts to secede from its territory. For example, the Balochistan Liberation Army has been active since 2000. In 2013 it attacked by rockets (by nearly demolishing it) the Residency in Ziarat where Muḥammad ‘Alī Jinnah, Qāʾid-e Aʿẓam (the Great Leader) and Baba-e-Qaum (Father of the Nation), spent his last days. In 2014, the home reopened after its reconstruction.

A current issue: the Syrian Civil War (2011-present)

Since 2013, protests against President Baššar al-Asad’s government resulted in the excesses of Syrian Civil War, with interventions of international armed forces. The outcomes are evident damage to cultural and artistic heritage of the country. Here are a few examples of major harms.

In Damascus, the partly-byzantine-style Umayyad Great Mosque, commissioned in 706 A.D. by al-Walīd I ibn ‘Abd al-Malik and at that time one of the biggest existing buildings, has been struck by mortars in its western front.

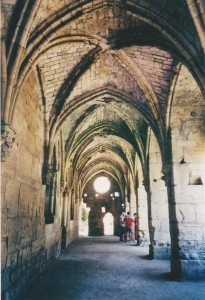

The two castles of Qal’aat al-Hosn (best known as Krak des Chevaliers, the stronghold and headquarters of the Knights Hospitaller) and Qal’aat Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn, among the world’s most important military castles that are still preserved, were targeted in attacks. The prior was bombed in July 2012 by Syrian military, because Free Syrian Army fighters, a group of defected Syrian Armed Forces officers aimed to bring down the system, were reportedly using the castle. This action damaged its walls and the inner historic chapel (photo 23 by author, right). Airstrikes continued in 2013 and 2014 until Syrian Army captured it in March.

The two castles of Qal’aat al-Hosn (best known as Krak des Chevaliers, the stronghold and headquarters of the Knights Hospitaller) and Qal’aat Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn, among the world’s most important military castles that are still preserved, were targeted in attacks. The prior was bombed in July 2012 by Syrian military, because Free Syrian Army fighters, a group of defected Syrian Armed Forces officers aimed to bring down the system, were reportedly using the castle. This action damaged its walls and the inner historic chapel (photo 23 by author, right). Airstrikes continued in 2013 and 2014 until Syrian Army captured it in March.

In addition to the destructions we have referred to at the top of this study, the ancient site of Palmyra sustained a military occupation and significant damage to its rich archaeological heritage: the Roman barracks of Diocletian’s camp have been damaged; a fortification has been built atop the ancient city wall; new defensive structures have been risen adjacent to the Qal’aat ibn Maan, the Druze Castle overlooking the archaeological site and dating back to the 13th century; snipers have been placed in the Roman theatre, and rocket launchers and tanks inside the archaeological site; looting have been occurring in the archaeological area since 2012.

In Homs, Khālid ibn al-Walīd Mosque (photo 24, right), built in Turkish National Renaissance style with Mamluk influence, has been completely destroyed in 2014, while in Hama a fire burned the upper part of the big Noria-Ga’bariyya waterwheel, one of 17 masterpieces used to take water from the Orontes River. Qal’aat al-Mudiq, a 12th century citadel in the same province, has been shelled, damaging the ancient fort walls.

In Homs, Khālid ibn al-Walīd Mosque (photo 24, right), built in Turkish National Renaissance style with Mamluk influence, has been completely destroyed in 2014, while in Hama a fire burned the upper part of the big Noria-Ga’bariyya waterwheel, one of 17 masterpieces used to take water from the Orontes River. Qal’aat al-Mudiq, a 12th century citadel in the same province, has been shelled, damaging the ancient fort walls.

In Aleppo, one of the world’s oldest continuously-inhabited cities and now victim of the most intense civil war combats, by September 2012 the fighting and the resulting fire have severely damaged its 14th century al-Madina aswāq (the ancient markets), the largest covered historic markets in the world, as well as the 15th century Ḥammām Yalbougha an-Nasry and Khan Qurt Bey, the mid-16th century Khusruwiye Mosque and the 19th century Carlton Citadel Hotel (both the latter now completely destroyed), the Grand Serail, the outer wall and the medieval iron doors of the Citadel, and other medieval buildings in the ancient city. In 2013, also al-Jāmiʿ al-Kabīr (photo 25 by Preacher lad, right), the Great Mosque undertaken in 715 by Umayyad Caliph al-Walīd I, suffered damage to the walls and courtyard, and its 11th century 46m-high stone minaret was reduced to rubble.

In Aleppo, one of the world’s oldest continuously-inhabited cities and now victim of the most intense civil war combats, by September 2012 the fighting and the resulting fire have severely damaged its 14th century al-Madina aswāq (the ancient markets), the largest covered historic markets in the world, as well as the 15th century Ḥammām Yalbougha an-Nasry and Khan Qurt Bey, the mid-16th century Khusruwiye Mosque and the 19th century Carlton Citadel Hotel (both the latter now completely destroyed), the Grand Serail, the outer wall and the medieval iron doors of the Citadel, and other medieval buildings in the ancient city. In 2013, also al-Jāmiʿ al-Kabīr (photo 25 by Preacher lad, right), the Great Mosque undertaken in 715 by Umayyad Caliph al-Walīd I, suffered damage to the walls and courtyard, and its 11th century 46m-high stone minaret was reduced to rubble.

Since the autumn of 2012, Buşrá ash-Shām and the southern Da’ara governorate have experienced tank shelling and bombing. Damage is limited to al-‘Umarī Mosque, while the Roman Theatre has been used by snipers, regularly shooting from it.

In the eastern city of Deir ez-Zor (a neighbourhood after the battle of October, 26th, 2014 in photo 26, right), a historic pedestrian suspension bridge has been shelled in 2013 and demolished in 2014, while the Armenian Genocide Memorial has been destroyed.

In the eastern city of Deir ez-Zor (a neighbourhood after the battle of October, 26th, 2014 in photo 26, right), a historic pedestrian suspension bridge has been shelled in 2013 and demolished in 2014, while the Armenian Genocide Memorial has been destroyed.

International agreements protecting religious and artistic heritage from attacks

In light of the above, abuses by warring parties on historical, artistic and architectural heritage are apparent, which implies not only a lack of sensitivity to the common feeling of affected populations and to the value of historical record, but also an infringement of international law according to the agreements and treaties regulating war laws and crimes. Below, the main international regulatory tools are cited as reference points to handle the matter:

- The Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907;

- Treaty on the Protection of Artistic and Scientific Institutions and Historic Monuments (or Roerich Pact) of 1935;

- Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, of 1949;

- The Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, of 1954;

- UNESCO Recommendation on International Principles Applicable to Archaeological Excavations, of 1956.

The second treaty of 1899 The Hague Convention, “with respect to the Laws and Customs of War on Land”, in the Section II “On hostilities”, forbids, moreover, “to destroy or seize the enemy’s property, unless such destruction or seizure be imperatively demanded by the necessities of war” (art. 23), and “the attack or bombardment of towns, villages, habitations or buildings which are not defended” (art. 25). It continues: “In sieges and bombardments all necessary steps should be taken to spare as far as possible edifices devoted to religion, art, science, and charity, hospitals, and places where the sick and wounded are collected, provided they are not used at the same time for military purposes” (art. 27), and it bans “the pillage of a town or place, even when taken by assault” (art. 28). Furthermore, in the Section III “On military authority over hostile territory”, the treaty says that “Family honours and rights, individual lives and private property, as well as religious convictions and liberty, must be respected. Private property cannot be confiscated” (art. 46), “Pillage is formally prohibited” (art. 47), “No general penalty, pecuniary or otherwise, can be inflicted on the population on account of the acts of individuals for which it cannot be regarded as collectively responsible” (art. 50).

The fourth treaty of 1907 The Hague Convention substantially confirmed and specify the provisions of the previous treaty on the matter.

The Roerich Pact, after the name of its Russian promoter Nikolaj Konstantinoviæ Rerikh, was signed in Washington D.C. Even though it has had a poor implementation, it’s important for its role in the development of international law to create a planned process to protect cultural property during war. Its main principle (not welcomed by the successive international regulations) is an unrestrained option to preservation of cultural values over military requirement.

Indeed, Part III “Status and Treatment of Protected Persons” of the IV Geneva Convention states: “Any destruction by the Occupying Power of real or personal property belonging individually or collectively to private persons, or to the State, or to other public authorities, or to social or cooperative organizations, is prohibited, except where such destruction is rendered absolutely necessary by military operations” (art. 53), somehow reaffirming what art. 23 of the second treaty of 1899 The Hague Convention had already expressed.

The Hague Convention of 1954 provides a detailed framework of regulatory formulations for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, particularly by qualifying definition, protection, safeguarding, and respect for cultural property, occupation of the whole or part of a territory, immunity of cultural property under special protection from seizure, capture and prize. A Second Protocol to the Hague Convention was adopted in March 1999.

The 1956 New Delhi UNESCO Recommendation on Archaeological Excavations, which is not legally binding, in its Section VI “Excavations in occupied territory” states: “In the event of armed conflict, any Member State occupying the territory of another State should refrain from carrying out archaeological excavations in the occupied territory. In the event of chance finds being made, particularly during military works, the occupying Power should take all possible measures to protect these finds, which should be handed over, on the termination of hostilities, to the competent authorities of the territory previously occupied, together with all documentation relating thereto” (art. 32).

A wish of hope

Definitely, international treaties and agreements are not enough to avoid havoc of architectural works and archaeological remains perpetrated in time of war, both for legal reasons (slipperiness of rules, ratification problems by individual countries, difficulties in incorporating legal provisions as mandatory rules), and for grounds of cultural policy, given the lack of training of civil and military authorities in approaching the issue, often felt not a priority over the warfare urgencies. Nor can we deal here with the thorny questions of identifying responsibilities, referral to the International Criminal Court and applying sanctions imposed by it.

The problem is cultural sensitivity, we said, and that sovereign institutions should adhere to a model of ethical behaviour, which demands, even in wartime, respect for the enemy, and especially for the historical legacy of its guiltless people. But, sadly, sometimes the State is hardly ethical!

I close by the words Paolo Gentiloni, Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation of Italy, said in the context of the “Protecting Cultural Heritage – An Imperative for Humanity” initiative, he presented at the UN in New York last September 27th: “Cultural heritage is a reflection of human history, civilization and the coexistence of multiple peoples and their ways of life. Its protection is a shared responsibility of the international community, in the interest of future generations”. And Irina Bokova, Director General of UNESCO, added: “Culture is on the frontline of conflict – we must place it at the heart of peace-building”.

Bibliography

- Bevan, Robert: The Destruction of Memory: Architecture at War, Reaktion Books, London, 2006;

- Boyd, Gary A., Queen’s University Belfast, UK and Linehan, Denis, University College Cork, Ireland: Ordnance: War + Architecture & Space, Ashgate, January 2013;

- D’Agostino, Glauco: Sulle Vie dell’Islam. Percorsi storici orientati tra dottrina, movimentismo politico-religioso e architetture sacre (Historical and Architectural Itineraries across the Muslim Countries), Gangemi, Rome, Italy, June 2010;

- Gorman, G.E. and Shep, Sydney J.: Preservation management for libraries, archives and museums, Facet Publishing, London, 2006;

- Lambert, Simon and Rockwell, Cynthia: Protecting Cultural Heritage in Times of Conflict, ICCROM, Rome, Italy, 2010-11;

- Lynn Schmidt, Victoria: Story Structure Architect, Writer’s Digest Books, Cincinnati, Ohio, 2005;

- Mancini, J.M. and Bresnahan, Keith: Architecture and Armed Conflict. The Politics of Destruction, Routledge, London and New York, 2015;

- Matthiae, Paolo: Distruzioni, saccheggi e rinascite. Gli attacchi al patrimonio artistico dall’antichità all’Isis, Mondadori Electa, 2015;

- Micewski, Edwin R. and Sladek, Gerhard: Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict – A Challenge in Peace Support Operations, Austrian Military Printing Press, Vienna, 2002:

- O’Keefe, Roger: The Protection of Cultural Property in Armed Conflict, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2006;

- Peeri, S.: Baghdad modern architecture and heritage, translated by J. L. Chehayed, Archange Minotaure publishing, Paris, 2008;

- Piquard, Brigitte and Swenarton, Mark: Architecture and Conflict. Introduction Learning from architecture and conflict, in The Journal of Architecture, Volume 16, Number 1, 2011;

- Posner, Eric: The International Protection of Cultural Property: Some Skeptical Observations, Chicago Journal of International Law 213, 2007;

- Prstojević, Miroslav: Forgotten Sarajevo, MI, Sarajevo / Wien, 2010;

- al-Radi, S.: War and Cultural Heritage: Lessons from Lebanon, Kuwait and Iraq, in De kracht van cultuur, Netherlands, October 2003;

- Ristic, Mirjana: Sniper alley: military urbanism of the besieged Sarajevo, in Between Architecture of War and Military Urbanism, ULD 10, Tallinn, 2013;

- Rossi, Aldo: The Architecture of the City, The Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts, Chicago, Illinois, and Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, New York, N.Y., 1982;

- al-Taie, Entidhar, al-Ansari, Nadhir and Knutsson, Sven: The Progress of Buildings Style and Materials from the Ottoman and British Occupations of Iraq, Journal of Earth Sciences and Geotechnical Engineering, vol. 2, no.2, 2012;

- Toman, Jiří: Cultural Property in War; improvement in Protection, UNESCO, Paris, 2009;

- Tresilian, David: Cultural Catastrophe Hits Iraq, in Al Ahram, April 24-30, 2003;

- Weizman, Eyal: The Hollow Land. Israel’s Architecture of Occupation, Verso, London, 2007.