The coexistence of concurrent Muftiates subsidiary of different aggregations on the territories finds the Kremlin’s disappointment. At the same time, the issue of their autonomy from the State and some manipulations for national purposes make a framework of conflict and uncertainty

By Glauco D’Agostino

Present situation after the progressive fragmentation of the historical Muftiate

Since the fall of the Soviet system, a problem of defining the Russian Muftiates (or alternatively a unified Russian Muftiate) has lasted. They are the Spiritual Administrations of Muslims (DUM) charged with steering verdicts especially on ethics and encouraging Muslim people to accept the State laws through an interpretation compatible with the Sharī’a Law. Institutionalised by Catherine II at the Orenburg Muslim Spiritual Assembly on September 22nd, 1788, the Muftiate operated in Ufa as a centralised body for all Muslims, first of the Empire and then of the Soviet Union, until 1943, when the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, urged by its President Mikhail Ivanovič Kalinin, authorised a corresponding Spiritual Administration of Muslims of Central Asia and Kazakhstan (SADUM) in Taškent; next year, those of Transcaucasia (DUMZ) in Bakı and of Northern Caucasus (DUMSK) in Bujnaksk, Dagestan, were born. Obviously, in May 1944 the Council for Religious Affairs (SDRK) under the Council of People’s Commissars authority was established, and it also included the activity coordination of religions other than Orthodox Christianity. In May 1965, control over the Christian Orthodox and the remaining communities was unified under the Council for Religious Affairs authority.

Today, Islam is officially represented by about 60 institutional entities at a territorial level, even though many of them are affiliated to two umbrella-organisations: the Central Spiritual Administration of Muslims of Russia, based in Ufa, Bashkortostan, and led by Tälğät Safa uğlı Tacetdin; and the Russian Council of Muftīs, established in Moscow and chaired by Rawil uğlı Ğəynetdinev. Both Tatar-born leaders bear the titles of Grand Muftī and Shaykh al-Islām, which identify the activity of Muftīs’ coordination. The second one had the historical function of spiritual and juridical-religious adviser to the Sultans, yet. Tacetdin epitomises the continuity with the Spiritual Administration of Muslims of the European part of the USSR and Siberia (DUMES, as the corresponding Muftiate had been called since 1948). He assumed its presidency in 1980, and this task was reiterated in 1992 when the DUMES had renamed Central Spiritual Board of Muslims of Russia and the European Countries of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CSBM). The current Central Spiritual Administration of Muslims of Russia (TsDUM) claims jurisdiction over the Russian Federation (excluding the territories of Krasnodar and Stavropol’ and the Republics of the North Caucasus) and extends its jurisdiction also to Belarus, Moldova and Latvia.

The other big umbrella-organisation, the 1996-born Russian Council of Muftīs, is a post-Soviet grouping and enjoys the advantage of its headquarters location in the federal capital, which allows it easier access to political and financial institutions. The Council harbours the Spiritual Administration of Muslims of the Russian Federation (DUM RF), renaming of a previous organisation once again chaired by Ğəynetdinev since its establishment in 1994; and since 1998 also the Tobol’sk-based Spiritual Administration of Muslims of the Asiatic Part of Russia (DUM AChR), chaired by the Siberian Tatar Grand Muftī Nafigulla Khudchatovič Ashirov, who is Co-President of the Russian Council of Muftīs, as well.

Grand Muftīs Tacetdin (left) and Ğəynetdinev (right) with His Holiness Kirill, Patriarch of Moscow and all Rus’ and Primate of the Russian Orthodox Church, and President Putin

The Spiritual Administration of Muslims of the Republic of Tatarstan (DUM RT) is a third pole ruled by Kamil Iskәndәr uğlı Sәmigullin [photo below] since 2013. Because of the presence of a “traditional” Islam also linked to the Naqshbandiyya Sufi Brotherhood, this Muftiate plays a role of historical resistance to the big institutional Muftiates (Naqshbandiyya has been an example of Sufi survival in the Soviet Union), as well as a task of political autonomy, which allegedly reflects its tendency to exercise foreign policy functions not always lined up with the Kremlin. The hint is to a pro-Turkish stance and supposed links with a certain neo-Ottomanism of some Turkish Naqshbandi circles. The contrast with the Russian Council of Muftīs has been evident even recently: attending the 6th Congress of Leaders of World and Traditional Religions, held in Kazakhstan last October 10th, Sәmigullin opposed Ğəynetdinev statements about the condition (absolutely sheltered, according to him) of Uyghurs living in the Chinese Xīnjiāng (which Tatars regard as their “blood brothers”). “How can a religious leader not react to anti-religious policies? We in Russia have treasured the lessons of history, and the negative consequences of the fight against religion for the whole society,” Sәmigullin countered.[1] The Council has obviously defended its Grand Muftī, stressing his mediation efforts with the Chinese government in favour of Uyghur Muslims.

The Spiritual Assembly of Muslims of Russia (DSM RF), a new umbrella-organisation, has been operating since late 2016, gathering around its President Al’bir Rifkatovič Krganov the DUM of Moscow and Central Russia, the Omsk, Kemerovo, Khanty-Mansi and Chuvashija Muftiates and some others more of the Volga Region. According to Alexey Malashenko, the Assembly would be born with the support of the Russian Orthodox Church.[2]

A problem still stands with the Russian Muftiates deriving from the jurisdiction of the Spiritual Administration of Muslims of the Northern Caucasus (DUMSK), which ceased operating at the USSR fall and was replaced by a homonymous body in the mid-1990s. Not to mention that the Council of Muslims of the Caucasus, heir to the Soviet-era DUM of Transcaucasia and operating from the Azerbaijani capital Bakı under the authority of the Shiite Grand Muftī Shaykh al-Islām Allahşükür Hümmət Paşazadə, declares its primacy, among others, on the Sunni Muftīs of Chechnya, Dagestan, Ingushetija, Kabardino-Balkarija, Karačaj-Čerkesija and Ad’igeija. However, the reality in the North Caucasus is quite different, due to the fragmentation of Muslims groups claiming administration authority, an internal rivalry and some ambiguities of the Muftiates stances. Suffice to mention the fact that all are affiliated collectively and simultaneously to both the Ğəynetdinev’s Russian Council of Muftīs and the Paşazadə’s Council of Muslims of the Caucasus, preferring the interest in at last affordable alliances. But the differences in the doctrinal approach of the various Muftiates reflect in each one’s action on the basis of the relationships they put on with the authorities of related republics or territories.

In Dagestan, Chechnya and Ingushetija, for example, the presence of Naqshbandiyya (in the version of its Khalidiyya branch) and Qādiriyya, which both entered the Caucasus from Turkey, causes a violent opposition to Salafist and Wahhābi doctrines deemed as “non-traditional”: indeed, Dagestan and Chechnya have banned Wahhābism by law, while it is not affected by federal law. In Kabardino-Balkarija, Karačaj-Čerkesija and Ad’igeija, a weak Sufi positioning and the prevalence of the Ḥanafī juridical-theological school have given rise to a more flexible religious policy, although the first of these republics has also outlawed the Wahhābi organisations since 2001. But within the Coordinating Centre of Muslims of the Northern Caucasus (KTs-MSK), an organisation established in 1998 to counter religious extremism and chaired by the karačaj Ismail Alievič Berdiev since 2013, tensions among Muftīs have come to such an extent as to threaten the exit of Dagestan and Chechnya Muftiates from the organisation. We must think that the latter Republic was the promoter of the Centre’s initiative. And in Ingushetija, Muftī Isa-Khadzhi Khamkhoyev recently “excommunicated” Yunus-bek Bamatgireevič Evkurov [pictured above with President Putin], the Head of the Republic who supports the dialogue between “traditional” and “unorthodox” Islam, “until he stops his discrimination against the clergy.”[3]

In Dagestan, Chechnya and Ingushetija, for example, the presence of Naqshbandiyya (in the version of its Khalidiyya branch) and Qādiriyya, which both entered the Caucasus from Turkey, causes a violent opposition to Salafist and Wahhābi doctrines deemed as “non-traditional”: indeed, Dagestan and Chechnya have banned Wahhābism by law, while it is not affected by federal law. In Kabardino-Balkarija, Karačaj-Čerkesija and Ad’igeija, a weak Sufi positioning and the prevalence of the Ḥanafī juridical-theological school have given rise to a more flexible religious policy, although the first of these republics has also outlawed the Wahhābi organisations since 2001. But within the Coordinating Centre of Muslims of the Northern Caucasus (KTs-MSK), an organisation established in 1998 to counter religious extremism and chaired by the karačaj Ismail Alievič Berdiev since 2013, tensions among Muftīs have come to such an extent as to threaten the exit of Dagestan and Chechnya Muftiates from the organisation. We must think that the latter Republic was the promoter of the Centre’s initiative. And in Ingushetija, Muftī Isa-Khadzhi Khamkhoyev recently “excommunicated” Yunus-bek Bamatgireevič Evkurov [pictured above with President Putin], the Head of the Republic who supports the dialogue between “traditional” and “unorthodox” Islam, “until he stops his discrimination against the clergy.”[3]

In the new Russian-ruled Crimea since 2014, the Muftiate is acted by the Religious Directorate of Muslims of Crimea and Sevastopol’ (DUMKS). Its Muftī Emirali Ablaev [photo below], who had already been at the helm of the Spiritual Direction of Muslims of Crimea (SDMC) since 1999, in the late October this year has been once again elected in Simferopol’ by the 6th Qoroltaj of the Crimean Tatars (the Great Assembly in the Mongolian tradition). This election was immediately refuted by Ayder Rustemov, who, in turn, had been elected in 2016 in Kiev Muftī of the DUM of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, in practice an independent branch alternative to the official Muftiate new course. This is because the DUMKS may no longer coordinate its action with the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People, which opposed the Russian annexation and has been declared an extremist organisation by the authorities. As a result, the Mejlis has worked for the birth of a new Ukrainian-based Crimean Muftiate. Another contrast among Muslims, yet, this time due to purely national political reasons, on both sides!

Thus, the Muftiates fragmentation has also led to the co-existence on the same regional areas of competing Islamic Spiritual Administration affiliated to different aggregations. In 2015, the Kurgan oblast’ had two Muftīs, the Siberian one of Tyumen’ (with the already mentioned Khanty-Mansi autonomous district) had three, and the Sverdlovsk’ (with the city of Ekaterinburg) even six, as Alexey Malashenko and Alexey Starostin report.[4]

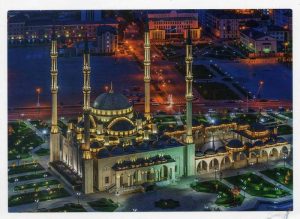

A mosque in Tyumen’

Muftiates function and relationship with the public authorities

The lack of a unitary authority representing the Islamic interlocutor to the institutions finds the Kremlin disappointment, also because it results in different attitudes of the same institutional bodies towards the organisations that alternately propose themselves as exclusive speakers of the Islamic requests on the same areas. This has raised a debate in the Muslim communities to the point of pushing someone to demand a return to the Soviet-era system when the Muftiates were real institutionalised subjects, even if this way the State while being secured about a loyal behaviour of believers, used them as control authorities of the related religious minorities and settlement lands. Right in the middle of the Stalin era and the aftermath of the establishment of a system based on four territorially defined Muftiates, the Council for Religious Affairs developed a debate about the usefulness of a single Muftiate on the basis of these issues:

- Uniformed program for organisational and administrative activities of the Islamic communities of the USSR;

- Centralised assistance to Muslims for the pilgrimage to Mecca and other holy places;

- Unified management of educational institutions, with the coordination and guidance of their activities;

- Coordinated actions in the release of magazines, prayer books and other printed materials;

- Coordination of the hospitality of foreign Muslim delegations hosted by the USSR.[5]

A final decision had been taken in 1949, when the Council, expression of a formally atheist regime, had spoken in favour of the status quo because a unified Muftiate would have risked strengthening the Muslim participation in religious life.

In light of these considerations, some stances are not certainly surprising, such as those Vladislav Kondratiev reported on Nezavisimaja Gazeta and referring to Nazymbek Aktazhievič Ilyazov, Chief of the Astrakhan Muftīs, when he states that “now it is essential to revive the Soviet tradition of governing the religious sphere of public life” and “Muslim Spiritual Directorates should work in the interests of the state” (Malashenko, 2018). These are emphases aimed at increasing collaboration with the authorities and reassuring them when faced with the extremism danger, although they raise a shadow of distrust over the issue of autonomy that the Muftiate should preserve vis-à-vis the State. Sәmigullin, the young President of the DUM of the Republic of Tatarstan, says: “Even though the religion is separate from the state it lives in the soul of our people.”[6] And Grand Muftī Ashirov adds: “A secular court should not pass judgments on the problems of Islam, and especially its sacred texts” (Malashenko, 2018). On the other hand, Ilyazov joined the TsDUM of Grand Muftī Tacetdin, who claims a full continuity of administration and functions with the Soviet period on a religious (not certain political) level, and ultimately the same religious approach in the attitude towards the State. But, according to Malashenko, it is the Russian Orthodox Church itself that rejects this approach that would undermine the principles of religious self-government.

However, loyalty to the Russian Federation is not questioned here. All the leaders of the main Muftiates – Tacetdin, Ğəynetdinev, Sәmigullin, Berdiev – support the Kremlin line regarding policy toward Muslim communities at home and abroad. The exception is Ashirov, who also joined the Russian Council of Muftīs and has raised concern for the Russian war in Syria and the resulting bombing. Moscow does not certainly worry about this, because it is aware that the destinies of the relationship with the Russian Islam lay on the responsiveness of the latter religious staff. The Muftīs’ cadres are renewing for age reasons and the young people going to hold the office open to new ideas. Depending on your point of view, this can be an advantage or a disadvantage.

Elderly people, all trained at the Bukhara Mir-i-Arab Madrasa [side photo by the author] (which is particularly important because it was the only operating one throughout the Soviet Union when the Communist atheism prevented any religious activities),[7] are reluctant to change but, on the other hand, ensure greater reliability from the perspective of political authority in terms of contribution to the training of believers respectful of institutional prerogatives. The new generation of Muftīs, which is not compromised by any collaboration with the Soviet system and well-versed in modern technologies, has a greater ability to reach the younger part of the faithful and influence their behaviour. Conversely, some raise doubts as to whether these Muftīs are actually able or not to be attractive in competition with other interests that the secularised world or vice versa the Islamic radicalism offer.

Elderly people, all trained at the Bukhara Mir-i-Arab Madrasa [side photo by the author] (which is particularly important because it was the only operating one throughout the Soviet Union when the Communist atheism prevented any religious activities),[7] are reluctant to change but, on the other hand, ensure greater reliability from the perspective of political authority in terms of contribution to the training of believers respectful of institutional prerogatives. The new generation of Muftīs, which is not compromised by any collaboration with the Soviet system and well-versed in modern technologies, has a greater ability to reach the younger part of the faithful and influence their behaviour. Conversely, some raise doubts as to whether these Muftīs are actually able or not to be attractive in competition with other interests that the secularised world or vice versa the Islamic radicalism offer.

In other words, the remark affects the function of Muftiates as reference points for the Islamic communities and whether for this goal they should pursue a path of “traditional” (Ḥanafī and Sufi) or “non-traditional” (Salafist and Wahhābi) Islam according to customs and traditions of the territories. But even more so, whether the Muftiate institution is still adequate to define the attitude of believers (especially the younger generations) or the latter self-rule in religious and political terms on the basis of other social components (political or civic movements). In this sense, what Gabdulla-khazrat Galiulla, Muftī of the DUM of Tatarstan from 1992 to 1998, stated is suggestive: “In a state with non-Muslim form of government where Muslims make up minority, it is only through political movements that the interests and rights of believers can be defended. It is the only way to influence on the decisions made by authorities.”[8]

It is a fact that since the perestrojka introduction and then the disastrous Soviet Union fall, the Muftiate institution is left weakened by the multiplication of subjects claiming legitimacy. It is hard to say, yet, how much any reasons of doctrinal affiliation, contrasts due to personal ambitions or a political push for autonomy by regional institutional players interested to intercept the consensus of authorities and communities in the Muslim world affected this weakening.

In the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s, the religious-political situation was knotty, and we give an account of this. The first Muftiate to fall was the DUM of Northern Caucasus in 1989 when the Muftī Maḥmud-ḥājji Gekkiev was ousted from his office on charges of having joined the Ḥanafī school and being unable to represent the Shāfi‘i faithful who are a majority in Chechnya, Dagestan and Ingushetija. The following year the Duma of Dagestan was born, the first in a series that would involve the other Muslim communities of Northern Caucasus on a regional basis. But also the Tacetdin’s DUMES, which was renamed TsDUM of Russia and the European countries of the Commonwealth of Independent States in 1992, began undergoing the first defections. The first one was the DUM of Bashkortostan, re-established by the new Muftī Nurmukhamet Magafurovič Nigmatullin, who is still at the Muftiate helm. Soon after, those of the Imām-Muḥtasib (Representative of the Muftiate) of the Republic of Tatarstan and several others of the Volga region and Siberia followed, all subsequently joining the DUM of the Central European Region of Russia, the forerunner of Ğəynetdinev’s DUM of the Russian Federation.

The political influence in the quarrels was particularly evident in Chechnya, Ingushetija and Dagestan, all republics more exposed to politicisation due to the more pronounced population affiliation to the Islamic faith: 96, 99 and 94% respectively. The touchstones were the 1994-96 and 1999-200 Russian-Chechen Wars. Already by the dissolution of the Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Socialist Republic in 1991 and the subsequent Chechen Republic of Ichkeria proclamation, young Chechen Imāms under the authority of the Naqshbandi Muftī Magomed-Bashir-ḥājji Arsanukaev of the newly-proclaimed DUM of Chechnya had not endorsed the separatist line of Chechen President Dzhokhar Musaevič Dudaev. But so would have the Qādiri Arsanukaev’s successors, first of all, Akhmad-ḥājji Abdulkhamidovič Kadyrov since 1993 and then Akhmad Shamaev since 2000, the same year Kadyrov became Chechnya acting Head. Both Muftīs opposed the breakaway theses by radical Islamism and its main political figures, such as Generals Shamil’ Salmanovič Basaev, Salman Betyrovič Raduev, Khunkar-Pasha Germanovič Israpilov and the Saudi Sāmir Ṣālaḥ ʿAbd Allāh al-Suwaylim (known as Amīr Khaṭṭāb) or the propaganda Head of the Republic of Ichkeria, Movladi Saidarbievič Udugov, and the Dagestani Wahhābi Mullāh Mukhammad Bagautdin. Conversely, in Ingushetija, a more fruitful agreement was established between the Muftī Shaykh Magomed Albogachiev and the two successive Presidents of the Republic Ruslan Sultanovič Aushev and Murat Magometovič Zjazikov [photo above], more inclined towards peace and stability of the region. It was perhaps for this reason that when the Coordinating Centre of Muslims of the Northern Caucasus (KTs-MSK) was born in 1998, Muftī Albogachiev assumed its presidency.

The political influence in the quarrels was particularly evident in Chechnya, Ingushetija and Dagestan, all republics more exposed to politicisation due to the more pronounced population affiliation to the Islamic faith: 96, 99 and 94% respectively. The touchstones were the 1994-96 and 1999-200 Russian-Chechen Wars. Already by the dissolution of the Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Socialist Republic in 1991 and the subsequent Chechen Republic of Ichkeria proclamation, young Chechen Imāms under the authority of the Naqshbandi Muftī Magomed-Bashir-ḥājji Arsanukaev of the newly-proclaimed DUM of Chechnya had not endorsed the separatist line of Chechen President Dzhokhar Musaevič Dudaev. But so would have the Qādiri Arsanukaev’s successors, first of all, Akhmad-ḥājji Abdulkhamidovič Kadyrov since 1993 and then Akhmad Shamaev since 2000, the same year Kadyrov became Chechnya acting Head. Both Muftīs opposed the breakaway theses by radical Islamism and its main political figures, such as Generals Shamil’ Salmanovič Basaev, Salman Betyrovič Raduev, Khunkar-Pasha Germanovič Israpilov and the Saudi Sāmir Ṣālaḥ ʿAbd Allāh al-Suwaylim (known as Amīr Khaṭṭāb) or the propaganda Head of the Republic of Ichkeria, Movladi Saidarbievič Udugov, and the Dagestani Wahhābi Mullāh Mukhammad Bagautdin. Conversely, in Ingushetija, a more fruitful agreement was established between the Muftī Shaykh Magomed Albogachiev and the two successive Presidents of the Republic Ruslan Sultanovič Aushev and Murat Magometovič Zjazikov [photo above], more inclined towards peace and stability of the region. It was perhaps for this reason that when the Coordinating Centre of Muslims of the Northern Caucasus (KTs-MSK) was born in 1998, Muftī Albogachiev assumed its presidency.

Ingushetija, Erzi Nature Reserve

The situation in Dagestan is much more manifold because the control of the Muftiate goes through the influence of the main ethnic groups settled there: the Avars, who are the foremost, the Dargwas, the Kumyks and the Laks. Following a Kumyk interlude at the top of the new DUMD, in 1992 the Avars, who already dominated in the Soviet era, conquered the primacy in the Muftiate with their candidate; but immediately, Laks, Kumyks and Dargwas established sequentially their own independent Muftiates, which those of Southern Dagestan and the Turkic Nogai minority added to. In 1994 the definitive turning point: the Dagestan government recognised the DUMD as the only Islamic authority on its territory and denied the registration to the Nogai Muftiate and its renewal to all other self-proclaimed Muftiates. After this decision, the Avars began a period of dominance together with the Sufi Brotherhood Naqshbandiyya, which the DUMD power practically relied on while counteracting its historical Wahhābi foes.

In the meantime, in the Republic of Tatarstan, a clash was ready within the DUM between two figures who, while opposing Grand Muftī Tacetdin’s intransigent defence of a strong and indivisible State, had divergent stances of each one relationship with the State itself: Gabdulla-khazrat Galiulla, Muftī of DUM RT since 1992, did not hide his annoyance at the interference President Mintimer ulı Şəymiyev did in religious affairs; Gusman-khazrat Iskhakov, one of the Tartar national movement ideologues already before the USSR fall, had as his programmatic basis the loyal collaboration with the State, from which the religious institutions expected the necessary aids. Galiulla had already started from the middle of the decade to forge links with nationalist movements, including the Party of Tatar National Independence İttifaq, which was the first non-Communist party in Tatarstan and since 1990 called for the recognition of the Tatar State as an international entity, the Milli Mejlis (National Congress), a body claiming the representation of the Tatar people interests; and the People’s Patriotic Union of Russia (NPSR) opposition party, whose leader Gennadij Andreevič Zyuganov, First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation, had challenged Boris El’tsin in the 1996 presidential election.

Showing up these not favourable references, Galiulla lost the Muftiate presidency in February 1998, when the opponent Iskhakov won the election with President Şəymiyev’s apparent support. The following year, the Parliament of Tatarstan approved the law “On Freedom of Conscience and Religious Organisations,” which regulated the State-Islam relations and recognised the DUM RT as the only centralised Islamic organisation representative of all the others. Moreover, this law recognised the special role of Islam in the history and society of the Republic, a similar recognition two years earlier the Duma of the Russian Federation had granted to the Orthodox Christianity with respect to Russia as a whole.

The unresolved issue of the Muftiates political role

In short, in the ‘90s all the main conditions fitting a redefinition of the authorities running the current Muftiates were made up, although new fragmentations and recompositions were not lacking even in the following decades. All the problems connected with this issue remain in the background and determine the difficulty of the relationship among the religious institutions. However, the debate continues brightly around a series of topics concerning not only religious issues in a strict sense but also the relationship of Islam with the society and institutions and ultimately its role in the political sphere. For instance:

- The lack of autonomy of the Muftiates, which are often treated as government agencies due to their control by the institutions at a territorial or federal level also because of financial provisions the latter make available to them;

- The recognition of a single religious institution by some local authorities, entailing not only an undue secular state interference in religious affairs but also the effect of pushing unrecognised organisations towards radical demands on a religious level and independentist stances on the political;

- The manipulation of Islam for political purposes (nationalist or for purely secular power), of which several regional leaders are accused, especially in the regions of the North Caucasus and Volga when they push for the connection of national and religious identities;

- The prohibition of founding political parties on a religious basis, which leads to a weakening of the social demands of those who naturally join forces around Islamic associations and do not find represented their interests in the institutional fora and a recognised leadership;

- The presence of foreign financial aids from Islamic countries towards internal religious activities (establishment of mosques, foundations, institutes and Islamic centres), which causes a dependence also in terms of religious practice and affiliation often not welcome on the territory;

- The emergence of so-called “Islamic radicalism” (basically the Salafist and Wahhābi movements), whose universal appeal is opposed both by the supporters of “traditional Islam” and the defenders of national specificities and often treated by the Russian Federation (wrongly or rightly) under the fight against terrorism.

The leaders of Russian Muftiates, but also the Kremlin and local authorities, will have to deal with these problems and demonstrate balance, responsibility and respect for the Islamic communities. The latter must recognise themselves as partakers of the great Russian soul, but in any case, they cannot give up either their history or tradition or belonging to a wider community, the Umma.

[1] Vladimir Rozanskij (November 8th, 2018). Moscow, Kazan, the Caucasus: divisions among the Muslims of Russia, from AsiaNews.it.

[2] Alexey Malashenko (February 2018). Islam in Today’s Russia, in Aldo Ferrari, Russia 2018. Predictable Elections, Uncertain Future, Ledizioni LediPublishing, Milano, Italy.

[3] Ingush Mufti unexplainedly absent from North Caucasus Muftiate conference (19 September 2108), from OC Media.

[4] Alexey Malashenko, Alexey Starostin (September 30th, 2015). The Rise of Nontraditional Islam in the Urals, Carnegie Moscow Center, Moscow, Russia.

[5] Renat I. Bekkin (2017). The Muftiates and the State in the Soviet Time: The Evolution of Relationship, in Z.R. Khabibullina, Российский ислам в трансформационных процессах современности: новые вызовы и тенденции развития в XXI веке (Islam in Russia during today’s transformation processes: New challenges and development trends in the 21st century), Уфимского научного центра Российской академии наук (Ufa Scientific Centre of the Russian Academy of Sciences), Dialog, Ufa.

[6] Glauco D’Agostino (2018). Tatarstan-Putin: A Crossed Challenge, Glimmer Publishing, London-Istanbul-Moscow-Delhi-Jakarta.

[7] Glauco D’Agostino (June 2010). Sulle Vie dell’Islam. Percorsi storici orientati tra dottrina, movimentismo politico-religioso e architetture sacre (Historical and Architectural Itineraries across the Muslim Countries), Gangemi, Rome, Italy.

[8] Azat Khurmatullin, Kazan Russian Islamic University (June 20th, 2008). Islam and political evolutions in Tatarstan, paper presented at the meeting Russia and Islam: Institutions, Regions and Foreign Policy, University of Edinburgh (UK), Old College.

Bibliography

- Bekkin, Renat (2017). The Muftiates and the State in the Soviet Time: The Evolution of Relationship, in Z.R. Khabibullina, Российский ислам в трансформационных процессах современности: новые вызовы и тенденции развития в XXI веке (Islam in Russia during today’s transformation processes: New challenges and development trends in the 21st century), Уфимского научного центра Российской академии наук (Ufa Scientific Centre of the Russian Academy of Sciences), Dialog, Ufa.

- Clifford, Bennett (21 September 2016). Sufi-Salafi Institutional Competition and Conflict in the Chechen Republic, in GeoHistory, School of Russian and Asian Studies (SRAS), Woodside, CA, USA.

- D’Agostino, Glauco (2018). Tatarstan-Putin: A Crossed Challenge, Glimmer Publishing, London-Istanbul-Moscow-Delhi-Jakarta.

- D’Agostino, Glauco (June 2010). Sulle Vie dell’Islam. Percorsi storici orientati tra dottrina, movimentismo politico-religioso e architetture sacre (Historical and Architectural Itineraries across the Muslim Countries), Gangemi, Rome, Italy.

- Halbach, Uwe (19 August 2009). Islam in the North Caucasus, in Archives de sciences sociales des religions [Online], 115, juillet-septembre 2001.

- Ingush Mufti unexplainedly absent from North Caucasus Muftiate conference (19 September 2108), from OC Media.

- Khurmatullin, Azat, Kazan Russian Islamic University (June 20th, 2008). Islam and political evolutions in Tatarstan, paper presented at the meeting Russia and Islam: Institutions, Regions and Foreign Policy, University of Edinburgh (UK), Old College.

- Malashenko, Alexey (February 2018). Islam in Today’s Russia, in Aldo Ferrari, Russia 2018. Predictable Elections, Uncertain Future, Ledizioni LediPublishing, Milano, Italy.

- Malashenko, Alexey and Starostin, Alexey (September 30th, 2015). The Rise of Nontraditional Islam in the Urals, Carnegie Moscow Center, Moscow, Russia.

- Ponarin, Eduard (April 2008). The Potential of Radical Islam in Tatarstan, Open Society Institute, International Policy Fellowship Program, Budapest, Hungary.

- Rozanskij, Vladimir (November 8th, 2018). Moscow, Kazan, the Caucasus: divisions among the Muslims of Russia, from it.

- Shikhsaidov, Amri (n.d.). Islam in Dagestan, CA&C Press AB, Sweden.

- Uppsala Universitet (6-8 October 2016). Abstracts and Biographies, International conference The Image of Islam in Russia, Institute for Russian and Eurasian Studies (IRES).

- Yemelianova, Galina (April 2014). Islam, nationalism and state in the Muslim Caucasus, in Caucasus Survey, 1, No.2, Taylor & Francis, London, UK.