The historical legacy, causes, warning signs, internal rivalries, the role of religious communities and their quarrelsome leaders, the British unease and cynicism. The mismanagement of the Indian Empire dismantling

By Glauco D’Agostino

Kashmir and Bangladesh: a legacy of old problems

Kashmir and Bangladesh: a legacy of old problems

Pakistan and India are on the outs once again. Last October 1st, military confrontation along the common border has been reopened in Jammu region, south of Kashmir, after two days earlier Indian “surgical strikes” were targeting militias within Pakistan-administered Kashmir, and after on September 18th anti-India militants had killed 19 soldiers in Indian-administered Kashmir. Actually, it’s nothing new to this troubled region, where skirmishes between the parties are commonplace. But the news (diplomatic, more than practice) is that India has claimed responsibility for military action, which is denied by Pakistan, along with a refusal of any Islāmābād involvement in attacks against India, as well. All this, while a strong independence movement is active in the Indian State of Jammu and Kashmir, which daily faces half a million soldiers sent on the spot from Dehlī to control protests.

Let’s step eastward. Last March 28th the Bangladesh Supreme Court rejected, “due to lack of applicant’s locus standi”, a petition advanced by the Committee against Autocracy and Communalism for removing the constitutional provision recognizing Islam as official religion of the State. “This is the decision of the highest court in the land. Islam should be the state religion. The majority of people in this country believe in Islam”, said Mawlānā Raquib, President of the Islamic Party Nizām-e-Islam, who added that religious minorities in the country will suffer no bias, because their rights are secured by the Constitution. Bangladesh People’s League, the secular nationalist and social-democratic-inspired ruling party since 2008, had already amended the Constitution in 2011, by inserting the norm of “secularism” and “equal status” of other religions, while it did not question the statement of Islam as the state religion introduced in 1988 by then-President Ḥuseyn Muḥammad Eraśād.

What is that combines in a single argument so distant and heterogeneous events as those listed above? Obviously, History and the awareness of its current impact on the future! The effects of a 1947 Indian Empire split as complex as it was poorly managed both by British rulers and the fractious Indian leadership, and that has left out on the field the unresolved issue of Kashmir Princely State and, following the Dominion of Pakistan proclamation, the East Bengal Province’s, as well: Kashmir was (and it is, yet) claimed by Pakistan and India, both heirs to the Indian Empire, and the mutual provisional border (Line of Control, pictured above and in the side map) is outlined according to the compromise Simla Agreement of July 2nd, 1972; East Bengal, following a nine-month war, declared its independence from the Islamic Republic of Pakistan in 1971, taking the name Bangladesh as a secular state, a principle later rejected in the Constitution of 1977.

What is that combines in a single argument so distant and heterogeneous events as those listed above? Obviously, History and the awareness of its current impact on the future! The effects of a 1947 Indian Empire split as complex as it was poorly managed both by British rulers and the fractious Indian leadership, and that has left out on the field the unresolved issue of Kashmir Princely State and, following the Dominion of Pakistan proclamation, the East Bengal Province’s, as well: Kashmir was (and it is, yet) claimed by Pakistan and India, both heirs to the Indian Empire, and the mutual provisional border (Line of Control, pictured above and in the side map) is outlined according to the compromise Simla Agreement of July 2nd, 1972; East Bengal, following a nine-month war, declared its independence from the Islamic Republic of Pakistan in 1971, taking the name Bangladesh as a secular state, a principle later rejected in the Constitution of 1977.

But this is not enough, because as for Kashmir, the only Muslim-majority territory within India, constant still ongoing tensions led to three major war crisis (in 1947, 1965 and 1999), raising fears for the geo-political stability of the area and even a possible nuclear conflict. As for Bangladesh, the achieved independence was not a cost-free, with allegations of genocide and deportations, still leading on the scaffold those presumed guilty. Such conflicts claimed the lives of over one million civilians, about 15 million people mass migrations, and consistent damage to public assets of all involved territories, as well as having jeopardized the mutual relations among three south-central Asian countries, which together add up over a billion and a half inhabitants.

How did it happen? Whom the blame should be assigned to? What are the causes and, especially, what have been the arrangements made to stabilize this area? The analysis below is meant to be a historical contribution to retrieve facts and characters, contexts and dynamics. Conclusions, of course, are up to each one, according to his judgment skills; politicians and diplomats are responsible for solutions. Surely, nobody could perform these functions if a realistic and shared historical framework is missing, as so often it’s done for ineptitude or bad faith.

Prior to WWII, “the sun never set” over the British Empire. India was the beginning of its decolonization process, despite UK was among the winners of the war, though in a subordinate position with respect to the two new super-powers, the United States and the Soviet Union. In 1946 Great Britain, urged by officially anti-imperial (at least in principle) pressure of the two global powers, had resorted to a loan of several billion US dollars, due to an inability to repay its war debts. In the next 20 years, nearly 700 million people under British rule would have achieved independence.

Thus, the first reason it withdrew from India laid in a lack of resources to control its vast territorial heritage, that in the past it had defended on the side at the cost of brutal repressions. While a fairly tidy dismantling and without major accidents occurred, the British error (or its cynicism?) has been not to accompany it with any political and diplomatic action that could avoid the bloodshed resulting from the withdrawal of its troops. Instead, a utilitarian attitude of “divide et impera” prevailed.

For over a thousand years people of different ethnic groups, religions and customs had been living together with many problems and tensions, but after all accepting to live side by side; indeed, they gave birth to syncretic forms of civilization. After the Indian Empire breakup, a real carnage took place, especially in Bengal and Punjab, with the religious components of the population, Hindus and Sikhs on one side and Muslims on the other, as main players.

The rise of Islam in India

Throughout its history, India, the Hindu tradition heart since 2000 B.C., had seen a gradual Muslim influence. Islam had spread to Indus Basin since 647, under the command of the Caliph ‘Uthmān ibn ‘Affān, and in 711 the Umayyad general Moḥammed bin Qāsim had occupied Sindh, the present Pakistani province where also lies Karachi, avoiding to cause a permanent control of the territory, but expanding the status of Ahl al-Kitāb (People of the Book) to Hindus and Buddhists, which were rooted in the area. In 778 a group of shipwrecked Muslims had settled in some villages of the Kingdom of Arakan (matching roughly the Rakhine State of current Myanmar) in its Western part (today within Bangladesh), and had given rise to a community that over time had become so powerful as to induce the King of Arakan to make war against it and defeat it in 954.

Preachers’ action in Bengal was equally effective: the Shiite preacher Bāyazīd al-Bisṭāmī, a Khorāsāni disciple of the 8th Shiite Imām ‘Alī ibn Mūsa ar-Riza, for eight years before his death (reached in 874) had been spreading Islam in Chittagong, where there is his mausoleum, yet. In 1053 Shāh Muḥammad Sultan Rûmî had settled in Netrakona, Northern Bengal, and from there had called to convert to Islam the King of Madanpur, who had agreed to the request. In 1179 Baba Shāh Adam, who would die as a martyr fighting the Hindu Raja Ballala of the Sena Dynasty, had reached Bikrampur, in the existing Munshiganj district, close to Dhaka.

The first actual territorial Islamic conquest in the Indian area had come in 1021, when the Ghaznavid Sultan Maḥmūd had conquered Lahore, Punjab, and had made it the Sultanate capital city; and in 1148 the Persian Sultans of the Ghurid Dynasty had established the 2nd Islamic State in northern India, capturing Dehlī in 1192, while maintaining Punjab up to 1215. In 1206 the Turkic Emir Quṭb ud-Dīn Aybak, first of a Mamluk Dynasty, had founded the Islamic Sultanate of Dehlī, which would have over time conquered almost the whole peninsula, and would have ruled again by Khilji, Tughlaq, Sayyid and Lodhi Dynasties until 1526, when the Mughal Empire would be based. Before the Sultanate of Dehlī founding, the northern part of Bengal had been taken to the Sena Dynasty, and before the 1290 Mamluk’s capitulation, the south-eastern area had fallen, as well, leading to voluntary collective conversions to Islam, especially among the Buddhists and the Hindu low castes. It would have to wait until XIV and XV centuries respectively to conquer Chittagong and the south-western section of the East Bengal.

Attempts from Indian origins to innovate Islamic doctrines had been very active. In the XIV century the Persian Master (Pīr) Ṣadr ud-Dīn al-Ḥusaynī, a descendant of the 6th Shiite Imām Ja’far aş-Şādiq, had reached India and had given birth to the specific syncretic religious variety of Nizārī Khojas, with elements stemming from different religions (Islam, Hinduism and ancient Persian forms of religion). In 1497 the Shiite cleric Syed Muḥammad Jaunpuri, regarded as the Māhdī by his followers, had started the Mahdavi movement in Badli, in the Indian Sultanate of Gujǎrāt, which, established in 1407, would be left independent until 1576. In 1575 the Mughal Emperor Jalāl ud-Dīn Moḥammad Akbar-e-Azam (the Great) (who was born and died as a Muslim) had set in the new city of Fatehpur Sikri the Ibādat Khāna (the House of Worship), at first open to Sunni Muslims, and six years later he had founded there the syncretic doctrine Dīn-i-Ilāhi (Divine Faith): the House had hosted the first multi-religious discussion group among Muslims, Hindus, Jains, Sikhs, Christians, Jews and even Parsi atheists, in order to discuss points and reasons of their different opinions.

In short, in a few centuries a hybrid Indo-Islamic civilization was born, by the onset of new expression forms, such as the Mughal and Punjabi architecture, and new languages, such as Hindi-Urdu and Deccani. Even from the religious point of view, a strong Sufi influence, especially in Bengal and Punjab, had acted as a bridge between the India-based religions, i.e. by acknowledging the divine character of sacred Hindu texts, and often by favouring manifestations of crossed popular religiousness, with Hindu believers visiting Muslim pīr’s mausoleums and Muslim faithful worshiping at the Hindu temples. But the mutual recognition had not been confined to popular piety, even involving the intelligentsia and ruling families: Among the Mughal, for instance, Prince Muḥammad Dārā Šukūh, the eldest son of the Emperor Shihāb ud-Dīn Moḥammad Shāh Jahān I, had stood out. He had translated from Sanskrit into Persian several Upaniṣad commentaries, and in his work Majma’ ul-Bahrain (The Mingling of the Two Oceans) had stressed the affinities between Sufism and Vedānta spiritual tradition; and Sultan Bahadur Shāh II, Emperor of Hindustān and the last Mughal Emperor, was an esteemed Ṣūfī, whom we owe the equating of Islam and Hinduism as parts of the same essence.

However, India in 1857, to the fall of Dehlī as an evidence resulting by the Mughal Empire and the Dynasty inaugurated by Tamerlane the Great, had been a prey to foreign interests already since the XVII century, and even more so the following century, once the British East India Company had undermined the Empire territorial integrity, gaining Bengal in 1757 at the Battle of Pôlashi and sweeping the rest of the sub-continent. In 1799 the Kingdom of Mysore had fallen after 400 years of its independence, and in 1818 the Maratha Empire, which 60 years before ruled almost the whole Indian peninsula, had suffered similar fate. In 1848 the British had dissolved the Sikh Empire (with a Muslim-majority population), and Punjab had become a province under Crown control. In 1858 the British Raj (with Calcutta as its capital city) was born, and in 1876 the political union of the areas directly administered by the United Kingdom and the Principalities under the British Crown had formed the Indian Empire.

The independence players and their responsibilities

This is the salient background. When starting the XX century and till 1948, the Indian vicissitudes are intertwined with the lives of some players of the Asian regional policy, whose mutual personal relationships and those with the British ruler on the issue of independent status will lead the destiny of the sub-continent peoples. Here are their main features prior to the Indian splitting:

- Mahātmā (Great Soul) Mohandās Karamchand Gāndhī, a Hindu with Jain influences, an anti-British nationalist and a supporter of non-violent resistance, a member of the religious and spiritual reform movement dedicated to emphasize the Hindu font of the Indian society, inspired by a Neo-Vedānta interpretation of Hinduism;

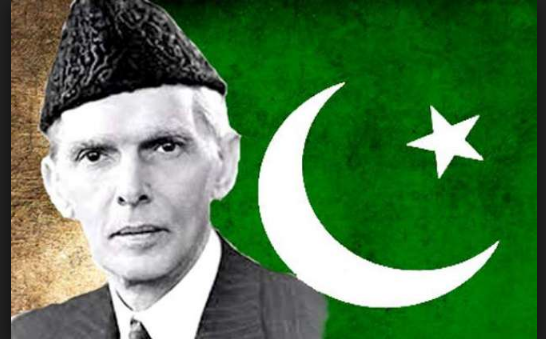

- Qāʾid-e Aʿẓam (Great Leader) Muḥammad ‘Alī Jinnah, a Sindhi Muslim Shia from an Ismaili Khoja family, a constitutionalist, a supporter of minority rights, leader of the All-India Muslim League;

- Paṇḍit (Brahmin) Javāharlāl Nehrū, an agnostic and secularist by Brahmin Kashmiri roots, a socialist and internationalist, but, like his mentor Gāndhī, affected by the political-religious movement Neo-Vedānta;

- Sardar (Commander) Vallabhbhai Jhaverbhai Patel, a Hindu and anti-Muslim nationalist;

- Mawlānā (Master) Abûl-Kalâm Muhiyuddīn Aḥmed Azad, a Sunni Muslim, a Bengali-rooted eclectic scholar born in Mecca, a secular-socialist, an exponent of the Indian independence movement and a supporter of non-violent civil disobedience, leader of the pan-Islamic movement Khilafat, virtually the sole major figure to advocate to the end India’s unity, with a common Hindu and Muslim partnership, without any discrimination.

The top four were all London-based educated lawyers; Gāndhī, Jinnah and Patel shared Gujǎrāti roots; all but Jinnah (who had been a member) had been Presidents of the Indian National Congress party: in short, all five came from a political and cultural background not so far from one another.

The responsibility of the Indian partition has been historically attached to Jinnah and his will to give the Muslim Indians a separate homeland vis-à-vis the Hindu majority. So, religious motivations. Perhaps, one should revisit the above judgment, in the light of the fact that the Shiite politician favoured non-confessional joint political solutions and a tidy transfer of powers, and also because, according to testimony of a colonial governor, he reproached Gāndhī (photo on the side) that “it was a crime to mix up politics and religion the way he had done”.

The responsibility of the Indian partition has been historically attached to Jinnah and his will to give the Muslim Indians a separate homeland vis-à-vis the Hindu majority. So, religious motivations. Perhaps, one should revisit the above judgment, in the light of the fact that the Shiite politician favoured non-confessional joint political solutions and a tidy transfer of powers, and also because, according to testimony of a colonial governor, he reproached Gāndhī (photo on the side) that “it was a crime to mix up politics and religion the way he had done”.

If this remake is accepted, the inference is that precisely Gandhi’s actions, valuable and effective in practicing a passive non-cooperation, assumed, however, those sectarian bases leaned to internal clash and disintegration, which were charged to Jinnah, instead. This would explain the efforts the latter made at the turn of the WWI for a partnership between the National Congress and the All-India Muslim League (which he simultaneously belonged to), as to be acclaimed “the Ambassador of Hindu-Muslim Unity” following the success of the Lucknow Pact of 1916, which had achieved an agreement between both parties and the purpose of submitting common Indian claims to the British. What did lead Jinnah (pictured below) after over thirty years from that event to call for the partition of India upon the granting of independence, denying a lifetime political battle for Indian unity? Possibly, answers could be found by analyzing the events of those three decades and the mounting rivalries and misunderstandings that occurred among Indian players of that time.

From Lucknow Pact to Nehrū Report

The starting point was precisely the content of the Lucknow Pact, which, among its qualifying aspects, included:

- The self-government principle, achieved through a popular election of 80% of representatives in the provincial legislatures;

- The separation between executive and judicial powers;

- Separate constituencies for all the communities;

- Muslim representation according to the share of 1/3 in the Central Government;

- 50% share of Indians in the Imperial Legislative Council;

- Abolition of the Council of the Governor-General of India, which was actually implemented just in 1935.

With the Government of India Act of 1919, the Crown meant to entrust “the elected representative of the people with a definite share in the Government” and point out “the way to full responsible Government”, by implementing a gradual decentralization process that would have led to a federal system. However, whereas the self-government principle was somehow incorporated in terms of formal powers transfer to the provincial authorities, liable to their respective elective Assemblies (and hence introducing a diarchic system), the excessive prerogatives vested in central powers in terms of exclusive areas of responsibility (in practice, with the Governor-General and his ministers, liable to the Crown) did not like to many Indians, who gave rise to non-violent protests, quickly crushed up to reach the Amritsar massacre, resulting in 380 casualties from each of the Sikh, Muslim and Hindu communities.

On the wave of popular discontent and even driven by purposes supporting an almost over Ottoman Caliphate, the same year the Mawlānās Muḥammad ‘Alī Jauhar, a founder and later President of the All-India Muslim League, Shaukat ‘Alī (brother of the above) and Hasrat Muhānī, along with other thinkers, established the pan-Islamic Khilafat movement. In 1920, Gāndhī, back to India four years earlier and by then National Congress leader, called the Khilafat movement and some major Muslim clerics (who agreed) to join the Non-Cooperation Movement headed by him, but he received a sharp opposition from both Jinnah and the All-India Muslim League, averse to disruptive actions, but also from Hindu Paṇḍit Madan Mohan Mālavīya, a former President of the National Congress. Just two years after its inception, Gāndhī’s Non-Cooperation Movement had failed and even the Khilafat movement, no longer backed by the Mahātmā, was downgraded in its task, also due to the Ottoman Sultanate collapse, followed in 1924 by the Caliphate millenary institution fall.

Nevertheless, their effects, as Jinnah predicted, had a serious impact on the separatist forces harmony, since the various components were now compacted on the basis of sectarian factors, rather than of regional, political and social ones. So, since interreligious cooperation was out, in 1923 the Hindu atheist Vināyak Dāmodar Sāvarakar was writing the pamphlet Essential of Hindutva (the Hindu condition), in which he advocated the establishment in India of a Hindu nation as an expression of ethnic, cultural and political separate identity with respect to the Muslim nation; within two years from, ārya samāja (the Noble Society), a movement maintaining Vedās infallibility, converted to Hinduism thousands of Muslim Rajputs, mainly in Punjab and the United Provinces of Āgra and Oudh; in 1925 the All-India Hindu Grand-assembly (Hindū Mahāsabhā), already born ten years earlier under another name, became a political party, and then fell under Sāvarakar’s influence and anti-Muslim theories opposed to National Congress policy. By contrast, the Deobandi Mawlānā Muḥammad Ilyas Kandhelvi founded the Tablīghī Jamā‘at (Society for Spreading Faith), in order to give Muslim population a separate State from Hindu-dominated India. In short, the seed of division had already been sown.

When in 1928, after several unsuccessful attempts by Indian inter-party conferences to produce a Draft Constitution at British request, a Commission chaired by Motilal Nehru (and very influenced by his son Javāharlāl) was established for this purpose, that seed germinated and became a first tangible step to an uncompromising disagreement. Because the resulting Nehru Report was obviously approved by the National Congress, but rejected by the Muslim League and by Jinnah, who denounced “shortsightedness and oppressiveness of Commission”. Jinnah tried again to rescue the agreement reached with the Congress, by proposing 14 points of eventual convergence, but they were repelled by his counterparts. And, after all, Jinnah was aware of representing a small minority in the hands of a majority deaf to requests not only of Muslims, but of all minority groups.

The major areas of disagreements were residing in the following matters, which were also the focus of the pointless meetings promoted in London between 1930 and 1932 to approach each other the Indian parties’ positions:

- Residuary powers arising from the federal structure found in both Constitution Drafts. Nehru Report gave them to federal centralized authorities, whereas Jinnah’s proposal conferred them to the Federated States’;

- Political representation of minorities. Nehru Report denied one of the Lucknow Pact contents, by refusing separate electorates (this principle would have been accepted by the British in 1932) and a proportionate weight to be given them in each Legislative Assembly, however granting Muslims a 25% share in parliamentary representation at central level. Instead, Jinnah’s proposal insisted on safeguarding minority rights at local level, therefore including provinces where not only Muslims, but also Hindus, Christians and Sikhs were in such a condition. In addition, it rose up the Muslim share at least to 30% in the Parliament and government representations at central level.

Of course, the respective positions reflected political ideas of their guiding principles: the national, unitary and socialist one of Javāharlāl Nehru, an advocate of a centralized planned economy; and that one of Jinnah, a proponent of decentralized powers vested in the federated entities, the latter more able to value ethnic and religious peculiarities of minorities, which would have been crushed by Hindu predominance at central level.

The “two-nation theory”

In 1930 the Punjabi poet and philosopher Sir Muḥammad Iqbāl (in the side image), regarded as the inspirer of the Taḥrīk-i Pākistān political movement (which would have led to the Northwest separation), said his inaugural speech in Allāhabad as President of the All-India Muslim League, stating: “I would like to see the Punjab, North-West Frontier Province, Sind and Baluchistan amalgamated into a single state. Self-government within the British Empire, or without the British Empire, the formation of a consolidated Northwest Indian Muslim state appears to me to be the final destiny of the Muslims, at least of Northwest India”. By claiming that in contrast to Jinnah, Iqbāl seemed to endorse the Sāvarakar’s “two-nation theory”, although from a right specular and antithetic position; but, while stressing the need for a State to Indian Muslims, he didn’t make any mention to the Bengal, which, too, was in the same status as a province whose population was predominantly Muslim (around 55%). Yet, Iqbāl was the main architect of Jinnah’s return to India in 1935, following his four-year self-imposed exile in London due to his intolerance of Indian politics and its figures. Since that time, Jinnah resumed Muslim League responsibility and control, possibly already inclined to continue his League leading forerunner’s road: he was getting ready to the Lahore Resolution, adopted by the Muslim League in 1940, where for the first time Jinnah would have joined the idea of a Muslim Pakistan detached from a Hindu India, even though in a fairly vague wording as to allow negotiations with the British.

In 1930 the Punjabi poet and philosopher Sir Muḥammad Iqbāl (in the side image), regarded as the inspirer of the Taḥrīk-i Pākistān political movement (which would have led to the Northwest separation), said his inaugural speech in Allāhabad as President of the All-India Muslim League, stating: “I would like to see the Punjab, North-West Frontier Province, Sind and Baluchistan amalgamated into a single state. Self-government within the British Empire, or without the British Empire, the formation of a consolidated Northwest Indian Muslim state appears to me to be the final destiny of the Muslims, at least of Northwest India”. By claiming that in contrast to Jinnah, Iqbāl seemed to endorse the Sāvarakar’s “two-nation theory”, although from a right specular and antithetic position; but, while stressing the need for a State to Indian Muslims, he didn’t make any mention to the Bengal, which, too, was in the same status as a province whose population was predominantly Muslim (around 55%). Yet, Iqbāl was the main architect of Jinnah’s return to India in 1935, following his four-year self-imposed exile in London due to his intolerance of Indian politics and its figures. Since that time, Jinnah resumed Muslim League responsibility and control, possibly already inclined to continue his League leading forerunner’s road: he was getting ready to the Lahore Resolution, adopted by the Muslim League in 1940, where for the first time Jinnah would have joined the idea of a Muslim Pakistan detached from a Hindu India, even though in a fairly vague wording as to allow negotiations with the British.

In the 1937 elections, the first with a separate electorate system under the provisions of the Government of India Act of 1935, the Muslim League failed to succeed: the party merely won 106 seats out of 491 reserved for Muslims, and among them 26 were gained by the National Congress. The latter, winner of a sound 42% of the seats up to 1,771 at stake, conquered Muslim strongholds such as the Bengal and North-West Frontier Province. In addition, in Bengal the Muslim League managed to secure just over 15% of the seats and in Punjab only two ones. With these results in its pocket, while the National Congress grabbed the executive leaderships in the States where it won (7 out of 11) and took part in two other governments, at the same time it followed a Javāharlāl Nehru’s intransigence, who refused to form coalition governments with the Muslim League where a reliable majority was failing to occur, as in Bombay and the United Provinces. It was a Nehru’s second political mistake after the 1928 Report, because since then a Muslim League and Jinnah’s revival would have begun precisely from the United Provinces.

When the UK declared war on Nazi Germany in 1939, and with no prior consultations it called India to its solidarity-based liability as an imperial colony, the Indian political leadership split again: the only ones who opposed the demand for participation in a undesired war were Gāndhī, on ethical grounds rooted in non-violence and non-cooperation, and the Bengali Hindu Netaji Subhāṣ Chandra Bose (to the side with Gāndhī in a picture of 1938), President of the National Congress, who was forced to resign due to disagreements with Gandhi as to use strength or not to force the British out of India; in the Congress itself, Nehru, Patel and Azad stated their collaboration on an equal footing, that is, in return for the immediate independence; Jinnah took a similar collaborationist approach he wanted to negotiate under a grant of greater rights for Muslims. Those positions recurred with regard to the Allied war against the Japanese, this time close to India; indeed, Bose went so far as to lead the Provisional Government of Āzād Hind (Free India) and the Indian National Army, both entities operating in Burma to support the Japanese Empire, since it had promised India’s independence after the British defeat; and Gāndhī resumed a stronger campaign of civil disobedience by the Quit India movement: in 1942 Nehru, Patel, Azad and Gāndhī himself were sent to jail because of that.

When the UK declared war on Nazi Germany in 1939, and with no prior consultations it called India to its solidarity-based liability as an imperial colony, the Indian political leadership split again: the only ones who opposed the demand for participation in a undesired war were Gāndhī, on ethical grounds rooted in non-violence and non-cooperation, and the Bengali Hindu Netaji Subhāṣ Chandra Bose (to the side with Gāndhī in a picture of 1938), President of the National Congress, who was forced to resign due to disagreements with Gandhi as to use strength or not to force the British out of India; in the Congress itself, Nehru, Patel and Azad stated their collaboration on an equal footing, that is, in return for the immediate independence; Jinnah took a similar collaborationist approach he wanted to negotiate under a grant of greater rights for Muslims. Those positions recurred with regard to the Allied war against the Japanese, this time close to India; indeed, Bose went so far as to lead the Provisional Government of Āzād Hind (Free India) and the Indian National Army, both entities operating in Burma to support the Japanese Empire, since it had promised India’s independence after the British defeat; and Gāndhī resumed a stronger campaign of civil disobedience by the Quit India movement: in 1942 Nehru, Patel, Azad and Gāndhī himself were sent to jail because of that.

From the Cabinet Mission Plan to the Provisional Government

At the end of the victorious war, the British resumed the vexed issue of India federal structure, previously proposed by Nehru Report of 1928 and at the time agreed in principle also by Jinnah. The purpose was to preserve the unity of India in a highly decentralized framework, aimed to a transfer of powers from London to Dehlī in view of an independence shared by everyone, the Crown included. At the same time, it was meant to curb Muslim League aspirations for a free and independent Pakistan.

In May of 1946 a Cabinet Mission Plan, drawn up under the responsibility of Lord Pethick-Lawrence, Secretary of State for India, was passed. Pethick-Lawrence, after consultations with the National Congress and the Muslim League, proposed a Federal Union of three autonomous constituent subjects and a central government to whom secure key competences for the Union security: the federated entities should have been three groups of provinces identified on a sectarian basis, referred to as Group A (the Hindu-majority provinces), B (the North-Western Muslim-majority provinces) and C (the Muslim-majority Bengal and the Hindu-majority Assam). In addition, 572 Princely States (which together numbered for a share of a quarter of the whole Indian population) were supposed to integrate with neighbouring provinces within the same group, unless popular electoral directions would have countered it.

The Pethick-Lawrence’s proposal displeased the aspiration of Punjabi Sikhs, who, especially for ancient historical reasons, were expressing anti-Muslim attitudes, why did not wish belonging to Group B and aspired, more concretely, to a national independence as a reward for their loyalty to the Empire during the just ended World War.

The Cabinet Mission Plan received Jinnah’s approval, but, apart from the ineffective Sikh opposition, also a refusal by Gāndhī, who took steps in this regard by inviting Assam to reject its placement in Group C along with Bengal. However, on July 7th the Congress expressed its consent to the Plan, by voting a formal resolution. At this point of the affair, an imponderable move occurs by a prominent protagonist of Indian politics, a three-time President of the National Congress and since 1941 appointed by Gāndhī as his political heir: we are speaking once again of Javāharlāl Nehru and his third, gigantic political blunder against Indian unity. Just three days after the Congress resolution, Nehru claimed the party did not feel bound to sign the Pethick-Lawrence’s Plan, except in the intention to establish a Constituent Assembly. Such a move was dropping the institutional setup of the Cabinet Mission Plan which, although reluctantly, also the Muslim League had joined.

Nehru was possibly tarnished in his political clearness by the ideological bias of the centralized state effectiveness, deriving by his adherence to socialist ideals, and was therefore unable to accept any form of decentralized power. Or, perhaps, he suffered a diktat of his guru Gāndhī, who was reluctant to any form of power-sharing with Jinnah and the Muslims. Difficult to judge. But, it’s sure, he failed to estimate the tragic effects deriving from his refusal to accept the British-initiative Plan. Or, he judged the partition of India as the best solution in order to retain power in its dominant part, with no interference by potential competitors, as well.

The fact remains that, as a reaction, also the Muslim League withdrew from the British Plan, justifying its rejection by the particular fluctuating attitude of the Congress and its leaders’ decisions, basically with no credit, mainly in view of coexistence under an independent institutional entity. Thus, also the Constituent Assembly elections were boycotted by the League, leaving the Congress the sole player of a constitutional representation. This breakdown had become irremediable, and since then the events were out of everyone’s control. When August 6th, 1946, the Muslim League called to a “Direct Action” as a day of peaceful protest, the event took place under the organizers’ intents, other than in Calcutta. For five days the Bengali metropolis had been rocking by violent riots that involved Hindus and Muslims in mutual killings and attacks, so as to cause 3,000 deaths and 17,000 injured, according to a report of the Viceroy Field Marshal Archibald Wavell.

While the Congress, on a surprising as inconsistent Gandhi’s invitation, accepted to agree on a partition of India statement, an interim government supported by the Viceroy’s Executive Council was established in September, and Javāharlāl Nehru took office as Council Vice-President with the powers of a prime minister. As the Muslim League realized the only interlocutor to the British in the transferring power process would have been the Congress, it joined the Executive Council in coalition with the Congress, and Liāqat Alī Khān, one of its most eminent leaders and a future Prime Minister of Pakistan, went to lead the Ministry of Finance.

The choice of a binary independence and its aftermath

On February 20th, 1947, the Labour Clement Attlee, British Prime Minister by the previous July, said the United Kingdom would have ruled India until June of 1948 as a deadline, while invoking Nehru’s and Jinnah’s responsibilities if no agreement will be reached. Admiral Louis Mountbatten, the new Viceroy since one week, became aware of the risks of civil war which India, with its multi-ethnic and multi-religious composition under a leadership already in mutual collision course, was exposed to. As a result, he spent his forces in favour of the partition as an alternative to civil war. Sadly, bloodshed happened anyway.

In March, the first reactions to Lord Mountbatten’s call: the Congress, by giving substance to the previous September resolution, considered the possibility to split India, but warned that, in the event of a Pakistan birth, also Bengal should have born as a separate state, West Bengal and East Punjab were supposed to belong to India, and 572 Princely States should have had a freedom to be part of Pakistan or India. It was clear this might become the winning proposal, but it disappointed the Jinnah’s ambitions to bring Bengal into Pakistan, in a single state; moreover, Punjab and Bengal maiming, with the resulting loss of Calcutta, as well, was likely to ignite hearts on the ground. Already in Punjab, along the proposed border, were beginning the first mutual massacres among Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs, foreshadowing what would have happened next.

In March, the first reactions to Lord Mountbatten’s call: the Congress, by giving substance to the previous September resolution, considered the possibility to split India, but warned that, in the event of a Pakistan birth, also Bengal should have born as a separate state, West Bengal and East Punjab were supposed to belong to India, and 572 Princely States should have had a freedom to be part of Pakistan or India. It was clear this might become the winning proposal, but it disappointed the Jinnah’s ambitions to bring Bengal into Pakistan, in a single state; moreover, Punjab and Bengal maiming, with the resulting loss of Calcutta, as well, was likely to ignite hearts on the ground. Already in Punjab, along the proposed border, were beginning the first mutual massacres among Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs, foreshadowing what would have happened next.

West Bengal, East Pakistan and Assam at the time of partition (by Frustrated Indian, January 4th, 2016)

On June 3rd, the Viceroy Mountbatten, following the approval from the Congress, Muslim League and Sikh community delegates, anticipated the transfer power date to next August 15th. However, nobody was ready to face a historical event in such a short span of time. Especially since the frontier lines which should have separated the States were not yet defined.

Nevertheless, the decision to separate India was already taken, and the Indian Independence Act was passed next June 15th with the okay of the Crown itself, which would have issued the Act consent next July 18th: basically, a compromise solution between Nehru’s and Jinnah’s positions, with Pakistan formed by Punjab and Bengal, but mutilated of large parts of their territories. Both India and Pakistan would have had a status of Dominion, a form of semi-sovereignty granted by the British Crown to an independent state, which recognizes the Sovereign of the United Kingdom of Great Britain as its Head of State. One of the provisions was significant, too: the acknowledgment that each Dominion was to be regarded as an expression of the self-government desire of Indian Hindus and Pakistani Muslims, thereby institutionalizing the sectarian components of the two territories.

When on August 14th Pakistan was already celebrating the transfer of powers a day before the set date, in order to give time to Lord Mountbatten of attending next day analogous ceremony in India, in the meantime the tragedy in one of the largest XX-century massacres was already underway, especially in Lahore and across Punjab, with the features and the figures mentioned at the beginning of this paper. And the words Jinnah said as Governor-General on his first address to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan were of no avail: “You may belong to any religion, or caste, or creed – that has nothing to do with the business of the State”, consistent with his decades-long battle in favour of religious freedom for all communities.

But this was only the beginning! It remained to settle an arrangement for the Princely States, which, out of the British Raj, had kept semi-independence within the Indian Empire. Following the establishment of the two Dominions, now they had to decide to join one or the other, according to the Indian Independence Act. Yielding to pressure from Lord Mountbatten, new Governor-General of India, and Sardar Patel, as Minister of Home Affairs, most of the Princes of all States within the boundaries of the new India acceded immediately to the request for joining the Indian Dominion. Junāgaḍh, Hyderabad and Jammu and Kashmir were an exception.

The prior, a State founded in 1730 in Gujǎrāt with the Mughal Emperor approval and a British protectorate since 1807, on August 15th asked for access to the Dominion of Pakistan, which accepted its instance a month later. Next November 9th, India replied, by taking Junāgaḍh militarily and imposing a referendum under occupation, which February 24th expressed the will of belonging to India. Hyderabad, a south-eastern sovereign State since 1724 and a British protectorate since 1798, decided to remain sovereign upon Indian independence. On September 17th, 1948, the Indian Army occupied the State and forced its Nizam to sign the Instrument of Accession to the Indian Dominion, resulting in circumstances of political and administrative instability that extend to current events.

The Kashmir situation was much more complicated, because of its geographical and political position. Lord Mountbatten’s strategic view, as recommended by the Congress, required that only the Princely States with a common border with the Dominion of Pakistan could choose to join it, and that was not the case of the two Princely States mentioned above. Conversely, the Himalayan State was in a position of actually choose. The problem arose from the fact that the Princely State of Jammu and Kashmir, with a 77% of the people adhering to Islam, was ruled by a Hindu believer Mahārāja influenced by the biggest local political group, an offshoot of the Indian National Congress. In this situation, the Mahārāja prevaricated, seeking to preserve his State independence. When in October the first uprisings occurred with Pakistan support, the Sovereign required Indian intervention, which, of course, led to the accession to the Indian Dominion. The aftermath was the First Indo-Pakistani War, which would be over two years later by an agreement between the parties under UN auspices. A portion of territory they called Azad (Free, in Urdu) Jammu and Kashmir, with Muzaffarabad as the capital city, was left to the Pakistanis; whereas most of the former Princely State, with Jammu as the winter capital and Srinagar as the summer one, remained in Indian hands. The situation is still unresolved to this day, with contrasting armed movements of both warring factions and a vowed never performed referendum.

Finally, another consequence from the long-term effects of the tragic fracture caused by the Indian Empire end is to be mentioned: the 1971 Bangladesh secession from the Islamic Republic of Pakistan (photo below, the declaration of independence). An event precisely matching Gāndhī’s and Nehru’s intentions in 1946-47 crucial years, under which Punjab and Bengal were not supposed to belong to a single State. Twenty-five years later, the purpose to split the Indian Muslim population, stubbornly countered by Jinnah, was finally caught up!

The ensuing Bangladeshi secular state attempted at first to push religion to the sidelines of civil and political life, in the presence of a population certainly not inspired by Gāndhī’s and Nehru’s ideological outcomes. Thus, if in the political life the laicist forces have unquestionably been the protagonists, as they still are today, however the civil substratum of Bangladeshi society continues to be persistently inspired by Islamic values. This restricts propensity to political abuses intrinsic in the strong nationalism of some local parties, possibly by virtue of an influence of several Sufi brotherhoods wise Pīrs been present for centuries in Bengal. Decades-long efforts to disown Islam as the official religion of the State bear witness to. Attempts always unsuccessful!