Failing unifying values, economic and political neo-colonialism is destroying the national model bloomed from independencies. The historical role of Islam

by Glauco D’Agostino

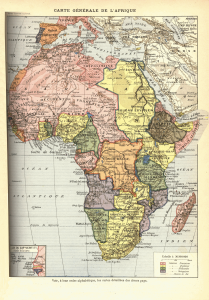

If we take a look at the Central Africa area, from Niger to Kenya and from Sudan to Congo, we will find a political map composed of States artificially drawn by XX century colonial powers (France, UK, Belgium, Italy, Spain), which, when granting them independence, spotted arbitrary frontiers, irrespective of population religious, ethnic and linguistic characteristics. We must acknowledge it would have been hard, such is the leakage of groups of different peculiarities and traditions on this territory. Then, the independence process has led to the aggregation of differing communities under a European-style centralized model of State, away from the setting of tribal autonomy and local chieftains charismatic command, typifying history of the area as a whole. Failing unifying values, the outcome has been a poor recognition of state authority, which gradually led to nations’ disintegration, as well as, for example, we are observing today in the political crises affecting Central African Republic, Nigeria, Sudan or Somalia. Nevertheless, exactly the latter land boasts an ethnic and linguistic unity which, however, did not prevent the breakup of the state structure and of public administration.

If we take a look at the Central Africa area, from Niger to Kenya and from Sudan to Congo, we will find a political map composed of States artificially drawn by XX century colonial powers (France, UK, Belgium, Italy, Spain), which, when granting them independence, spotted arbitrary frontiers, irrespective of population religious, ethnic and linguistic characteristics. We must acknowledge it would have been hard, such is the leakage of groups of different peculiarities and traditions on this territory. Then, the independence process has led to the aggregation of differing communities under a European-style centralized model of State, away from the setting of tribal autonomy and local chieftains charismatic command, typifying history of the area as a whole. Failing unifying values, the outcome has been a poor recognition of state authority, which gradually led to nations’ disintegration, as well as, for example, we are observing today in the political crises affecting Central African Republic, Nigeria, Sudan or Somalia. Nevertheless, exactly the latter land boasts an ethnic and linguistic unity which, however, did not prevent the breakup of the state structure and of public administration.

The countries instability in the area is testified by its numerous successive coups since 1963: 4 in Niger, 3 in Tchad, 5 in the Central African Republic, 3 in Congo-Brazzaville, 1 in Congo-Kinshasa, 6 in Nigeria, 3 in Sudan, 1 in Somalia, 3 in Ethiopia, 1 in Equatorial Guinea, 3 in Uganda. Nearly half of them involve former French colonies.

Today, the outline of the institutional leaders holding executive power is very diverse in terms of religious beliefs and political areas they belong: out of 19 Heads of State or Government, 11 are Christians (according to Catholic, Anglican, Oneness Pentecostal, Eritrean Orthodox faiths) and 8 are Muslims, the latter being usually distributed in the Sahel and Horn of Africa; with regard to the ruling political groupings orientation, half of them have reference to the traditional allocation of European parties (Conservatives, Socialists, Social-Democrats), the others being divided into Nationalists, Islamists, pan-Africanists, independents and even a Marxist-Leninist coalition. Three countries led by nationalist formations (South Sudan, Eritrea and Uganda) have Christian leaders, and the ruling party in Eritrea is the only legally recognized; Ethiopia, with a Christian Prime Minister, is led by a Marxist-Leninist coalition, the Premier being its leader.

Thus, political scene is a multicolored one, and there are various religious, administrative and political experiences. However, the causes of the national scheme failure in Central Africa are political at all, and must be sought at least in the way former colonial powers (and not only) run some crucial situations, such as:

- energy resources control;

- influence on internal adjustments and foreign policy;

- selection of the State top and political class, both imposed by the interests of previous colonial Administrations through military intervention or more or less legitimate political support.

Exogenous politico-economic management

Especially the oil resources management gives a picture of foreign influences, at least on the States with relevant reserves. For example, in Tchad the entire production is shared among Exxon Mobil (40%) and Chevron Texaco (25%), both from US, and Petronas (35%), from Malaysia; in Gabon the French Total, the Anglo-Dutch Shell and the Anglo-French Perenco together reach 80% of total national production; again Total holds a 70% share both in Cameroon and in Congo-Brazzaville; Shell in Nigeria (in joint venture with Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation) reaches 50%, but significant interests are also operated by Exxon Mobil, Chevron Texaco, Total and the Italian ENI.

However, oil sector is not an isolated case, because this outline is not different for the mining resources of which this area is rich, such as uranium from Niger, coltan from Congo-Kinshasa or other commodities of remarkable economic value (gold, diamonds, cobalt, chromium, bauxite, and so on).

In such a context, it’s important the role of China, which, lacking the burden of a colonial history, bases its African policy on investments and assistance for local development, rather than relying on a policy of French-style military intervention. So, today the Asian giant invests primarily in Sudan, Ethiopia and Nigeria (whom activities almost 100,000 Chinese work in) and grabs 15% of African exports (compared with the US 17%), mainly from Nigeria, Sudan, Congo-Kinshasa, Equatorial Guinea, as well as Angola.

The United States is interested in the Sahel and Gulf of Guinea countries on the oil grounds, and in South Sudan and Somaliland also for the defense of the Red Sea shipping routes. On a commercial level, it has been effective through the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) since 2000. Even Russia and India are in this area: the first one especially in Nigeria, with Rusal, the largest company in the world in the aluminum sector; the latter, by derivative interests in Tchad and Equatorial Guinea, as its African economic diplomacy is carried out in West Africa through the Techno-Economic Approach for Africa-India Movement (TEAM-9).

Influences on foreign and domestic policies and management of military crises

Francophone States and France political legacy

The French-speaking area of Central Africa stretches along its western half, with the exception of Nigeria and by adding Djibouti. France holds the advantages and also the historical responsibilities resulting from its dominance: in fact, it enjoys privileged ties with many countries, due to Francophonie, to agreements with them concerning military cooperation, to the strong economic presence in this area, and to the not merely economic influence explicated through the activities of its multinational operating in the energy sector. It weighs on its actions the legacy of Françafrique, namely the neo-colonial policy put in place after the independencies season, in order to keep influence on its prior colonial empire countries through political, economic and military relations, not always being transparent and supposedly parallel with respect to incumbent governments. For example, there are still shadows about its former support to the military dictatorships in Tchad, Cameroon and Congo-Brazzaville, and those ones on the actual motivations of frequent military interventions (even today), formally justified by humanitarian reasons or conflict prevention. Many voices, however, have hinted to clientelist relations or to the establishment of networks funding political parties in France.

In addition, a major role in strengthening links to France are deemed to be Masonic connections among some influential politicians, particularly Presidents Denis Sassou Nguesso, Idriss Déby Itno and Ali Bongo Ondimba, respectively Grand Masters of Congo, Tchad and Gabon Grand Lodges; former President François Bozizé of the Central African Republic, right initiated by Nguesso; probably (but “dormant”) also Paul Barthélemy Biya’a, President of Cameroon. However, this has not prevented quarrels amongst their respective nations, as evidenced by the lack of solidarity to Bozizé, when he has been overthrown last year.

The Central African Republic is one of the most striking samples of these policies consequences. Since last August 15th, it has been suffering the secession of Dar al-Kuti north-central region by insurgents of Séléka coalition. But, before that, it has undergone several coups since its 1960 independence: the reciprocal ones by progressive Catholics Jean-Bedel Bokassa in 1966 and by his cousin David Dacko in 1979, both backed by France; that one by Catholic Gen. André-Dieudonné Kolingba in 1981; the one by Celestial Christian Gen. François Bozizé Yangouvonda in 2003, supported by Tchad; the one by Muslim Michel Djotodia Am-Nondokro in 2013. Just Ange-Félix Patassé, a Catholic and socialist politician, came to power as a result of 1993 election, but after being involved in the 1982 coup plot against Kolingba. Destabilizing factors are associated with this institutional instability, such as ethnic-religious domestic conflicts, a weak border control, a Lord’s Resistance Army turn-out (from Uganda), guerrillas from South Sudan, Darfur, Tchad and Congo-Kinshasa; all these factors resulting in the attendance of soldiers from all the aforementioned nations, aside from French (who hold some bases) and US troops (fighting Lord’s Resistance Army), and not to talk about possible infiltration of Shabaab (out of Somalia) and Boko Haram (from Nigeria) guerrillas.

The Central African Republic is one of the most striking samples of these policies consequences. Since last August 15th, it has been suffering the secession of Dar al-Kuti north-central region by insurgents of Séléka coalition. But, before that, it has undergone several coups since its 1960 independence: the reciprocal ones by progressive Catholics Jean-Bedel Bokassa in 1966 and by his cousin David Dacko in 1979, both backed by France; that one by Catholic Gen. André-Dieudonné Kolingba in 1981; the one by Celestial Christian Gen. François Bozizé Yangouvonda in 2003, supported by Tchad; the one by Muslim Michel Djotodia Am-Nondokro in 2013. Just Ange-Félix Patassé, a Catholic and socialist politician, came to power as a result of 1993 election, but after being involved in the 1982 coup plot against Kolingba. Destabilizing factors are associated with this institutional instability, such as ethnic-religious domestic conflicts, a weak border control, a Lord’s Resistance Army turn-out (from Uganda), guerrillas from South Sudan, Darfur, Tchad and Congo-Kinshasa; all these factors resulting in the attendance of soldiers from all the aforementioned nations, aside from French (who hold some bases) and US troops (fighting Lord’s Resistance Army), and not to talk about possible infiltration of Shabaab (out of Somalia) and Boko Haram (from Nigeria) guerrillas.

Anglophone States and Britain political legacy

For English-speaking area of Central Africa we mean Nigeria (the only country where English is the main language), two States of the Great Lakes region (Uganda and Kenya), and some north-eastern African countries (Sudan, South Sudan, Eritrea and Somaliland). Despite the long colonial rule (excluding Eritrea), we must say UK today has no large strategic interests in this area, except for oil of Nigeria and Gabon.

Some of the major problems of internal stability are just focused in Nigeria and South Sudan, two oil-producing countries. South Sudan, following its 2011 secession from Sudan, is experiencing ever deeper tribal rivalries, with the emergence of new rebel leaders in various internal States, and a growing militarization of crisis. Especially former Vice President Riek Machar, a native to Nuer tribe, is launching the greatest attacks on President Salva Kiir Mayardit, a Dinka; this highlights a power struggle within the ruling conservative party, which led to independence and now is failing to transform into political action the premises established when it was guerrilla movement. There remains the interference phantom of the Ugandan army, expressly invited to intervene by Kiir’s government.

Nigeria was set up in 1914 by the British colonial authorities, through the merger of the Northern region (inhabited by Hausa and Fulani ethnic groups, mainly Muslim and generally more homogeneous among them) and the South (mostly Christian and animist Yoruba and Igbo, usually less consistent also in terms of linguistic and political aggregation). A higher opposition to British (and Western world in general) revealed by northern people comes from this framework, also because of attitudes of Hausa elite, which in the past has been manipulated by the colonial power to subdue local populations. Today Nigeria is plagued by many problems: endemic corruption, the quarrel about oil wealth share, a bloody Islamist insurgency, and ancient ethnic, sectarian and religious disputes. Since January 1st, 2014, with the expiry of the Treaty 100 years ago sealed the reunification of North and South Protectorates, a coalition of various ethnic groups, under the aegis of the New Nigeria Movement (NNM), has been calling for a country restructuring.

Nigeria was set up in 1914 by the British colonial authorities, through the merger of the Northern region (inhabited by Hausa and Fulani ethnic groups, mainly Muslim and generally more homogeneous among them) and the South (mostly Christian and animist Yoruba and Igbo, usually less consistent also in terms of linguistic and political aggregation). A higher opposition to British (and Western world in general) revealed by northern people comes from this framework, also because of attitudes of Hausa elite, which in the past has been manipulated by the colonial power to subdue local populations. Today Nigeria is plagued by many problems: endemic corruption, the quarrel about oil wealth share, a bloody Islamist insurgency, and ancient ethnic, sectarian and religious disputes. Since January 1st, 2014, with the expiry of the Treaty 100 years ago sealed the reunification of North and South Protectorates, a coalition of various ethnic groups, under the aegis of the New Nigeria Movement (NNM), has been calling for a country restructuring.

Current US initiatives

Two new US initiatives involve Central Africa:

- Security Governance Initiative for Africa (SGI), which is aimed at improving internal and foreign investments security in some African nations, and that extends to Niger, Nigeria and Kenya, too;

- African Peacekeeping Rapid Response Partnership (A-PREP), designed to enhance the ability of military intervention for peace, and that also extends to Ethiopia and Uganda.

Both of them, being presented as actions to protect human rights, seem to have, instead, geo-political purposes: on the one hand, strengthening the economic control of the area, competing with France and China, given that, in Washington intentions, the target of exports from Africa assigned to US should reach 25% in 2020; on the other hand, to counteract al-Qāʿida in the Islamic Maghreb, Hizbul Shabaab and Boko Haram Islamist groups; and even more, to reinforce some currently ruling political systems, including repressive regimes, definitely not human rights champions (see Ethiopia and Nigeria). Surely, these two initiatives will not help those peace missions African Union operates through the UN; in fact, they seem to be alternative or opposed to them and seem to reaffirm the new African policy triggered by George W. Bush by U.S. Africa Command, and to set out a new season of military interventions. Things we wouldn’t do for human rights!

The historical role of Islam

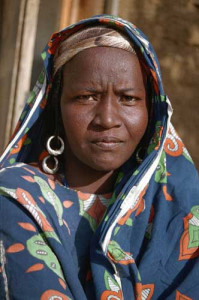

In Africa, Islam, as in its nature, has often been a response to social claims, first of all steadying community and overcoming slavery and social castes. The failure of secular, progressive and nationalist ideologies and associated protest movements has enhanced the Islamist network social role, sometimes resulting in jihādist phenomena so much concern a distracted West. Conversely, rarely Western countries have expressed interest in the reasons of discomfort outbursts, opposing State absence and corruption; all motivations that have paved the way for an invocation of the Sharī’a Law as juridical remedy of last resort: it bears witness, during the season of Azawad independence, the behavior of local Malian people, welcoming the jihādist militants of ʾAnṣār ad-Dīn or the pan-Islamists of the Movement for Oneness and Jihād in West Africa (MUJAO). This is not that is the tendency of Sahelian and sub-Saharan Islam, which, indeed, has always been watered to mysticism of the Sufi Brotherhoods. It does mean, instead, that certain maximalist trends derived from Middle East (specifically Wahhābi and Salafist ones) overlapped the essentially spiritualistic inclination of Maliki-compliance African behavior, although some ṭuruq resorted to jihād as a way of religious struggle against colonialism (see examples of Almamy Amadou Sheikou Tall of Toucouleur and Faama Samory Touré of Ouassoulou); and, in any event, this does not imply that all Salafists of the area have embraced violent forms of struggle.

Sure, ignoring there is a widespread feeling of dissatisfaction towards a model of Western culture imposed by neo-colonialism (especially since the 80’s of the last century), leads to an error of sociological and political analysis on a rising interest for religious movements, whose root is criticism to current uniformity and standardization of society, and that has an Islamic counterproposal as its goal, closer to the community sensitivity. The methods used to assert these proposals are a separate issue, and, in this regard, condemnation of violence as an approach of political struggle is obvious.

Islamist resistance in Nigeria

The most explicit example is provided by the condition Nigeria lives towards religious extremism. Historically, British did not occupy an empty territory, without institutions and lawless. In the north they inherited the Sokoto Caliphate, that, after its foundation by Sheikou Usman dan Fodio in 1803, thirty years later would have become a true theocracy, ruling 70 years even on present Niger and Cameroon territories, before being absorbed into the British Protectorate and treated like any other Emirates of the State. From there, a call by some to historical legitimacy of the Islamic institution, a call opposing the artificiality of a secular State of colonial origin, in contrast to the approach of traditional religious teachings. This is the choice made by revolutionary Mahdism as early as 1905-06, when not only the British and French colonial powers were under attack, but the “quisling” aristocracy and clergy, as well: British and French replied with brutal crackdowns.

Among the Sufi Brotherhoods, Qādiriyya had a privileged role in Nigeria, because it was selected by the colonial power as the cornerstone of local administration and as a bridgehead to the native population, especially in regard to the sort of education to be introduced and the use of English language. Tijāniyya, instead, such as Mahdism, choose the defense of Islamic education as its own flag, an argument becoming topical again, as we will report below. But first, we need to mention two anti-Western protest movements that grew in the second half of the ‘900:

- the Talakawas (i.e., the commoners), which began in the north by the socialist Aminu Kano in the late 40’s, in a wake of popular dissatisfaction towards the British management via the elite of local tribal leaders. Afterwards, this protest would have been channeled to the foundation of Northern Elements Progressive Union (NEPU), which was the main opposition party in the 50’s self-government period and called for a “class struggle against the ruling class”;

- that one led by the Hausa preacher Maitatsine (The one who damns, Moḥammed Marwa’s pseudonym), who, by proclaiming himself Mujaddid (religious Renewer) and later even a Prophet, launched in the late 40’s a pauperistic and anti-modernist campaign, that cost him repeated arrests by the British authorities and his exile, as well. Then, his movement would have been active for many decades, even after his death in 1980.

Since he had these examples behind him, in 2002 in Maiduguri, the Borno State capital, Moḥammed Yūsuf founded Boko Haram, a mediatic popularization of Jamāʿat Ahl as-Sunna li-d-Daʿwa wa-l-Jihād movement (Group of Sunna People for Preaching and Jihād), a Salafist group aiming to counter the Nigeria westernization, by introducing Sharī’a Law, and with the political purpose of establishing an Islamic State in the north of the country. According to some analysts, the reasons for his rootedness in Borno (particularly amidst Kanuri people) would be not so much the battle against the model of education introduced by British (Western education is sin), but a desire for social justice and the fight versus corruption: therefore, political reasons, resulted in claims that, since 2009 (the year of the founder’s assassination), have been thinking a radicalized Islamism as the political form of struggle deemed more effective and visible. However, both Amīr al-mu’minīn Muḥammadu Sa’ad Abubakar IV, the qādir Ṣūfī Sultan of Sokoto, and the Coalition of Muslim Clerics in Nigeria, have publicly condemned the group actions. At the same time, Jamāʿatu Anṣāril Muslimīna fī Bilādis Sūdān (Group for the Protection of Muslims in Black Africa), in short Anṣāru, is a jihādist Salafist movement born in 2012, as a Boko Haram splinter group.

Since he had these examples behind him, in 2002 in Maiduguri, the Borno State capital, Moḥammed Yūsuf founded Boko Haram, a mediatic popularization of Jamāʿat Ahl as-Sunna li-d-Daʿwa wa-l-Jihād movement (Group of Sunna People for Preaching and Jihād), a Salafist group aiming to counter the Nigeria westernization, by introducing Sharī’a Law, and with the political purpose of establishing an Islamic State in the north of the country. According to some analysts, the reasons for his rootedness in Borno (particularly amidst Kanuri people) would be not so much the battle against the model of education introduced by British (Western education is sin), but a desire for social justice and the fight versus corruption: therefore, political reasons, resulted in claims that, since 2009 (the year of the founder’s assassination), have been thinking a radicalized Islamism as the political form of struggle deemed more effective and visible. However, both Amīr al-mu’minīn Muḥammadu Sa’ad Abubakar IV, the qādir Ṣūfī Sultan of Sokoto, and the Coalition of Muslim Clerics in Nigeria, have publicly condemned the group actions. At the same time, Jamāʿatu Anṣāril Muslimīna fī Bilādis Sūdān (Group for the Protection of Muslims in Black Africa), in short Anṣāru, is a jihādist Salafist movement born in 2012, as a Boko Haram splinter group.

The Sufi ṭuruq in East Africa

This sub-Saharan Islamism roundup cannot end without, at least, having hinted at the beneficial presence of Sufism in East Africa. There are numerous Brotherhoods established on this area, and among them we must mention the following:

- the Qādiriyya, which marked the first Sufi presence in the region, when Sharīf Abū Bakr al-ʿAdanī ibn ʿAbdullāh al-ʿAydarūs imported it in the second half of the XV century from his native Yemen to Harar, in eastern Ethiopia. From there, it spread in the rest of Ethiopia (especially in today Somali Region), in Sudan and in Somalia (by pivoting on the town of Hargeysa, the “little Harar” and current Somaliland capital);

- the Sammāniyya, widespread in Sudan and Ethiopia;

- the Tijāniyya, born in Fès, Morocco, but influential also in Sudan, as well as in West Africa and in northern Nigeria;

- the Aḥmadiyya-Idrīsiyya, via its Sanūsiyya, Mīrġanīyya, Khatmiyya, Rashīdiyya and Ṣāliḥiyya offshoot. In XIX century, Sanūsī soon expanded from Cyrenaica to the Sahelian region of present Tchad and Sudan; instead, the Mīrġani family from Mecca was responsible for the establishment and introduction of Mīrġanīyya and Khatmiyya in this area, and Sīdī Muḥammad al-’Uthmān Mīrġanī al-Khatim developed the second one, especially in Sudan, Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somalia; in the latter operated the Sudanese Ibrāhīm ar-Rashīd bin Ṣāliḥ ad-Dunqulāwī ash-Shāʾiqī ad-Duwayhī and mainly his son Muḥammad;

- the Burhāniyya, founded in the XIII century and renovated in the XX by the Sudanese Shaykh Mawlānā Moḥamed Osman `Abdu’l-Burhāni.

Towards the colonial authorities, some of these ṭuruq proved to be moderate and sympathetic, such is the case of Mīrġani in Sudan and in general the Qādiriyya. The most combative of them seemed to be the Ṣāliḥiyya by the action of the religious Sayyīd Muḥammad `Abd Allāh al-Ḥasan, who in 1896 established the Dervish State in the Horn of Africa heart, and for two decades, during the Anglo-Somali War, kept in check the imperial forces of Great Britain and its Italian and Ethiopian allies, before it fell in 1920, i.e. after the defeat of the Ottoman Sultanate, which had recognized it.

Perhaps, current affairs of Somalia and of entire region (see also South Sudan and Eritrea) lugging misunderstood reasons in managing this colonial legacy: another political howler, yet, originated after World War I by the victors. Exactly as in the Middle East!