The need to restore the Monarchy as a guarantee of recovering stability and security in the country

by Glauco D’Agostino

The March 25th public statements of Libyan Foreign Minister, Moḥamed Abdelaziz, while attending a preparatory meeting for the 25th summit of the Arab League in Kuwait, have revived the Monarchy option as an adequate institutional solution to face the situation of disconnection Libya is experiencing after the Gaddafi’s regime overthrow.

This news item, first relaunched by the Saudi daily Okaz, shows how a debate on the Sanūsī’s recall at the helm of the State is up-to-date, both at a grassroots and the national top level. “Many tribal sheikhs, who lived under monarchy and know it, prefer such a system of government”, the Minister added. Then, after explaining his personal commitment to engage communities, even beyond his own government post, he has motivated the need for restoring Monarchy as a guarantee of recovering stability and security in the country, by calling for the retrieving, revising and updating of the 1951 Constitution, which many observers believe one of the finest fundamental laws of modern times. That Constitution, before the abolition of the federal system of government in 1963, united under a constitutional Monarchy the three regions of Tripoli, Barqa (Cyrenaica) and Fezzan and had two capital cities: Tripoli and Benghazi. This model, according to Abdelaziz, is what ensures the unity of the Nation, a dynastic legitimacy, loyalty of tribal population, the separation between the Monarch representative powers and the actual ones of the federal government, the tangibility of a free and real opposition. “When we talk about royal legitimacy, we mean centrist values, the Sanūsī movement and the history and loyalty for late King Idrīs as-Sanūsī”, he explains. And many observers, even among the Westerners, think another politically active head of state does not meet the expectations of impartiality the Libyan people require.

The judgment review towards Sanūsī by the new Libya was soon become clear when the revolutionaries had hoisted the Kingdom of Libya flag and had begun singing the anthem of the monarchist Libya and when both had turned the official symbols of the new State. Then, last February, then Prime Minister ʿAlī Zīdān had submitted to the General National Congress (the legislative body) a draft law repealing the rule that exiled the royal family. Two months ago, on March 5th, the interim government decided to “rehabilitate” the royal family, giving citizenship to its members and providing the juridical framework for the restitution of property confiscated after the 1969 coup.

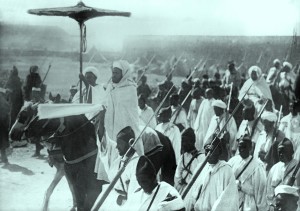

The ability to act for unity and identity, that is attributed to Sanūsī as leaders of the Libyan people, has been established because of the characteristics of their history, that join religious and political aspects, poured over an area free from ethnic homogeneity, with no national experiences before 1951, and strongly rooted in the religious beliefs of its community. Sanūsī first gave local populations an ethical and behavioral concern through Sanūsiyya, the reformist Sufi Brotherhood founded in 1837 in Mecca by their forefather Sharīf Sayyid Muḥammad ibn ‘Alī, the Grand Sanūsī; then, by acquiring a connotation of militant Islamism, have provided them with a political awareness and gradually have become their natural leaders. In summary, here is their ascent:

- in 1840, with the founding of az-Zāwiya al-Bayḑā’ (the White Monastery), in the Ottoman Cyrenaica, they give life to an embryonic structure of government, which collects taxes, controls the pilgrimage routes to Mecca and keeps peace among tribes; and then spread in the Saharan oases of the south-eastern Cyrenaica (from Jaghbūb to Jof and Kufra), of Tchad, Darfur, Sudan, and even in Nigeria, Egypt and the Arabian Peninsula;

- with the onset of anti-colonial struggles countering French and Italians, they stand out, inspired by pan-Islamist ideals, through the insurgent exploits of Sayyid Aḥmad ash-Sharīf Pasha, Moḥammed el-Barrani and Sīdī ‘Umar al-Mukhtār;

- in 1913, by declaring a jihād against Italy (which the year before had stated that land its Protectorate), they proclaim the independent State of Cyrenaica, which will fall three years later;

- in 1917 Italy assigns to Sayyid Muḥammad Idrīs, later to become King of Libya, the administration of the inland areas (with the title of Amīr of Kufra, Jaghbūb, Jalo, Aujila and Ajdabiya oases) and the right to keep armed forces;

- in 1948, following the Italian defeat in the WWII, Sayyid Idrīs resettles in the palace of the former Italian Governor and forms a government in Benghazi, where March 1st, 1949 proclaims the Emirate of Cyrenaica;

- October 7th, 1951 the Libyan National Assembly approves the Federal Constitution, laying down the independence of the United Kingdom of Libya from Great Britain and France, former occupying powers under UN auspices;

- next December 24th the Amīr Idrīs, under the name of Idrīs I, becomes Sovereign of the new kingdom.

The unanimous consent received from King Idrīs was founded on three basic assumptions:

The unanimous consent received from King Idrīs was founded on three basic assumptions:

- a profile of legitimacy, given the fact Sanūsī are ʾAshrāf, namely descendants of the Prophet Muḥammad through Ḥasan ibn ‘Alī, and thus enjoy a broad consensus across the Islamic world;

- a politico-religious profile, since he’s rooted in the Sufi and tolerant doctrinal line of Sanūsiyya (especially for the acceptance of legal interpretation driving it away from the Wahhābis) and in its moderate political approach, not necessarily hostile to the Western world;

- an inter-ethnic profile, since Sanūsiyya does not represent any of the 140 major Libyan tribes.

The Mu‘ammar Qaḏāfī’s coup in 1969 breaks down this tribal balance, since the influential Arabized Berber Qaddadfa tribe is in a privileged position compared to the other: in this sense, the Sanūsiyya banning by the regime has been a serious political mistake, because of the sudden lack of a major mediating element, which only in recent years the government and the Libyan Military have discreetly sought to retrieve. Not least because Saif al-Islām, the Gaddafi’s second son and the most available to dialogue with some anti-regime forces, was a son of Safia Farkash, who, in turn, belonged to al-Bara’asi tribe, traditionally close to King Idrīs.

Since the 2011 Revolution, domestic issues about power management have emerged, such as the atavic theme of relationship between central government and tribes, but also the role of the rebels’ armed militias in this dramatic period of transition. As for the first subject, Libyan public opinion seems to be again inclined towards the rejection of relying on single tribe hegemony, thus rediscovering, once more, the positive function performed in the past by the Sanūsī Monarchy. As regards the second point, right Minister Abdelaziz urged the establishment of an atmosphere of institutional harmony, able to include in the national political debate also those who, in the absence of efficient army and police forces, is at this time defending the country from potential external attacks: “They believed in a new Libya and in the state of laws and rights. How can you exclude those field leaders? They have the right to contribute to building the State, legal institutions, the army and the police force. When that’s done, whoever wants to join the army is welcome. But, marginalizing field leaders at this stage is wrong and unfair”.

Of course, the Minister’s words are to be contextualized in this specific confusing time, when rebels overflow to an extent of implementing striking actions, partly due to their political marginalization; at a time when serious events shake Libyans’ civic consciousness, such as the kidnapping of Prime Minister ʿAlī Zīdān in October 2013; at a time when first Fezzan last September and then, the following November, Cyrenaica (renamed Barqa, as in 1951) state regional autonomy and inaugurate their territorial governments.

But the main risk Libyan society is running are an addiction to chaos and the consequent refusal recognizing any state authority. This lack of territorial control by the institutions is causing once again to seek a solution both monarchical and Islamic, just to prevent the collapse of the unitary State and any subsequent secession and to avert the hazard from religious extreme fringes satisfying foreign regional powers.

Now, after the election of the Constituent Assembly last February, it’s widely believed the State institutional form should be debated in all its possible options and the Libyans are entitled to be consulted on. If a constitutional Monarchy might be reintroduced, two members of Sanūsī dynasty may contend for the throne:

- Prince Sayyid Moḥamed ar-Riḍa bin Ḥasan (son of Sayyid Ḥasan ar-Riḍa al-Mahdī, failed successor designated by King Idrīs), 51, who lives in exile in London and has already been contacted by Minister Abdelaziz to test his availability;

- Sayyid Idrīs bin ‘Abdullāh (belonging to a side branch), 57, former businessman in the oil industry living in exile in Rome. He married the Spanish aristocratic Ana María Quiñones de León, a cousin of King Juan Carlos.

Moḥamed’s supporters claim the rights of direct lineage from the last King; but Idrīs’ proponents oppose that Moḥamed’s father has abdicated after the 1969 coup and that, in any case, the succession to the Brotherhood leadership has never been established according birthright, but via election of a member of Sanūsī family by the Council of the tribal leaders. However, none of the possible pretenders to the throne has publicly claimed that role in the post-Gaddafi era: e.g., Idrīs said he favours popular election of a Head of State, whatever you choose to call it; Moḥamed said he did not believe his return to the throne of Libya is timely, yet; even the 81-year-old Aḥmed az-Zubayr, grandson of the 3rd Grand Sanūsī Field Marshal Sayyid Aḥmad ash-Sharīf Pasha and at present promoter of the Cyrenaica autonomy, declared he’s a Republican. But everyone knows that caution exhibited by Sanūsī could match, in truth, a lack of internal and international guarantees that their legitimately established eventual kingdom may not be later hypocritically thwarted, due to unavowable ambitions on the use of energy resources or to abrupt geo-political changes.

Surely, Sanūsiyya is lacking neither the Islamic premises nor the political credentials in order to be legitimated at a popular level and it resume its rightful role in the history of Libya. After all, Sayyid Ḥasan ar-Riḍa al-Mahdī (Moḥamed’s father) has been suffering for 19 years the toughness of Gaddafi’s prisons, until a stroke left him paralyzed. And the other branch leaders, both the aforementioned Aḥmed az-Zubayr and Sayyid ‘Abdullāh (the claimant Idrīs’ father), have been working to overthrow Gaddafi, particularly in the operations known as “Fezzan” and “Hilton Assignment”: following allegations for insurgency, Aḥmed has suffered 31 years of detention (including 18 on death row and 9 in seclusion), so today you may understand his desire not to get involved too much in the political affairs of Libya. Then, since 1990 Sanūsiyya has started acting as coordinator for several opposition figures; and in 2005 in London the National Front for the Salvation of Libya, the Monarchist Party led by Fayez Jibril and Ibrāhīm Sahad, and six other political groups organized an opposition meeting, from which arose the National Accord, in order to restore the constitutional order envisaged by the 1951 UN resolution. The same year negotiations between the regime and some Islamic groups were starting, resulting, through Saif al-Islām’s conciliation, in measure of pardon to 132 political prisoners, including 84 Muslim Brotherhood members.

Also during the 2011 Libyan Revolution, the voice of Sanūsiyya has not failed to be close to the people’s anguishes and both Moḥamed and Idrīs and Aḥmed have encouraged fighting for freedom, by involving, at the same time, the international community to alleviate the suffering caused by the bloody conflict.

Ultimately, the proposed return to the Sanūsiyya reconciling power does not match a claim (even if legitimate) of the royal family, but an effective need of the young Libyan Nation to regain freedom and peace, within a framework of institutional and political balance to be recognized by the entire population. This decision – Sanūsī also acknowledge it – is in the hands of the Libyans and their political and tribal representatives. It also lies in the international community recognition that there is no more appropriate solution to stabilize the country (and the North-African area as a whole) than a recourse to traditional Islamic basics, in this particular case to a political-religious institution that gave rise to the Libyan Nation, basing it on the mediation implicit in the Sufi moderatism of the Sanūsiyya Brotherhood.